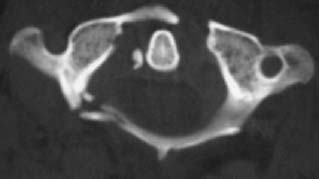

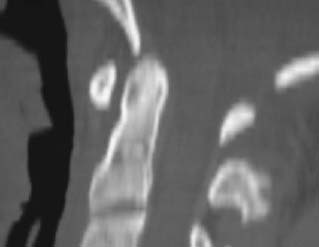

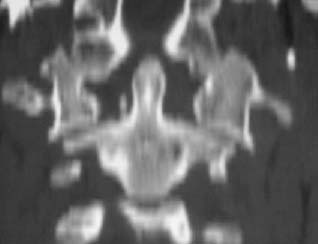

CASE 106 Hema N. Choudur, Anthony G. Ryan, and Peter L. Munk This patient presented with multiple injuries following a motor vehicle accident. No neurologic deficit was noted. Figure 106A Figure 106B A fracture of the posterior arch of C1 is evident on the lateral views (Figs. 106A and 106B [enlargement]). Displacement of the lateral masses of the atlas is evident on the C1–C2 open-mouth view (Fig. 106C, open mouth). The CT images (Fig. 106D, axial; Fig. 106E, sagittal reformat; Fig. 106F, coronal reformat) reveal bilateral anterior and right posterior arch C1 fractures with suspicious discontinuity of the transverse ligament and displacement of the lateral masses by 7 mm. Jefferson’s fracture. None. Burst fractures of the atlas were originally described as four-part fractures by Jefferson in 1920. However, a review of the literature, radiographs, and CT studies indicates that the majority are two-part fractures. An axial force produces these fractures, which may be stable or unstable. Any suspicion on plain radiographs is confirmed with CT. The management varies depending on the stability of the fracture. Most cause no neurologic sequelae. Figure 106C Figure 106D Figure 106E Figure 106F Fractures of the first cervical vertebra (C1) account for 7% of all acute cervical spine fractures. Isolated atlas fractures are most commonly bilateral or multiple fractures through the C1 ring. Frequently (in 44% of cases), the atlas is fractured in combination with the axis. An axial loading force, like a diving injury, causes the atlas to break, with splaying of the fracture fragments. In the classical Jefferson’s fracture, it is striking that there is no fracture of the atlas, which may be due to simple symmetric compressive force. Flexion, extension, oblique flexion, and extension with axial tilting are the various mechanisms involved in variants of Jefferson’s fractures.

Jefferson’s Fracture

Clinical Presentation

Radiologic Findings

Diagnosis

Differential Diagnosis

Discussion

Background

Etiology

Pathophysiology

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree