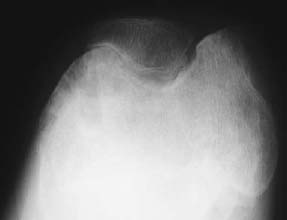

CASE 129 Anthony G. Ryan and Peter L. Munk A 25-year-old man presented with a chronically painful knee, having experienced spontaneous dramatic knee swelling. Figure 129A Figure 129B Figure 129C Anteroposterior (AP), lateral, and skyline views (Figs. 129A–129C) of the right knee show a dense joint effusion and osseous changes consistent with advanced degeneration, that is, large subchondral cysts, irregularity, and sclerosis of the osseous articular surface with marginal osteophytosis. There is overgrowth of the medial epiphysis in particular. Valgus deformity is evident. The intercondylar notch is widened. The joint space is narrowed; however, it is relatively preserved, given the severity of the other changes present. The inferomedial aspect of the patellofemoral joint demonstrates the most marked joint space narrowing. Hemophilic arthropathy. In patients with severe hemophilia (< 1% of factor VII:C), 85 to 90% of all bleeding events involve the joints, frequently occurring spontaneously. The frequency and severity of bleeds decrease with increasing levels of the factor. Musculoskeletal bleeds account for most of the morbidity associated with the condition, although transfusion-related human immunodeficiency virus (HIV) remains the most frequent cause of death (intracranial hemorrhage was more common in the pre-HIV era). This is an X-linked recessive condition occurring in 1 in 500 to 1 in 10,000 males, causing deficiency of coagulation factor VIII:C (hemophilia A), and in the case of Christmas disease, factor IX (hemophilia B). Although transmissible, it should be remembered that as many as one third of hemophilias are secondary to sporadic genetic mutations or deletions. The initial bleed occurs in the synovium and extends into the joint space. Repeated hemorrhages cause ongoing irritation of the synovial lining, resulting in chronic synovitis. The hypertrophied synovium is hyperemic and more prone to injury, leading to a cycle of bleeding, synovitis, and further bleeding. The hypertrophied synovial membrane causes progressive degeneration of the articular cartilage, commencing as fissuring and extending to erode the cortical and subchondral bone. The characteristic large subchondral cysts are thought to be secondary to the pannus and additional intraosseous hemorrhage rather than the invariable superimposed secondary osteoarthritis. Intra-articular blood, elevated intra-articular capsular pressure, and proteolytic enzymes released by leukocytes and inflamed synovium contribute further to cartilaginous and osseous erosion. Increased blood flow secondary to chronic synovitis causes periarticular osteoporosis (exacerbated by the immobility induced by the pain), epiphyseal overgrowth, and premature physeal closure. The synovium becomes infiltrated by plasma cells and monocytes, followed by hemosiderin deposits and adhesions, leading to subsynovial fibrosis. The subsynovial fibrosis develops early and is later accompanied by intra-articular and capsular fibrosis, leading to joint contractures. Fibrosis within and around the joint further impairs cartilage nutrition. In acute hemorrhages, the joint capsule may become distended with blood and diminish the range of motion. In addition to spontaneous hemarthroses, 15 to 30% of hemophiliac bleeds are extra-articular, occurring along fascial planes, within muscle, and within bone. Intramuscular bleeds are most common in the quadriceps and iliopsoas muscles. Repeated hemorrhage occurs more frequently into the joints than into the gastrointestinal or genitourinary tracts in patients with hemophilia. Most patients have their first hemarthrosis between 1 and 5 years of age. After the age of 10, bleeds occur less often. Typically, the same joint suffers the repeated hemorrhages. With acute hemarthrosis, the patient complains of pain in the joint, which, on examination, is tense, red, and warm with a markedly decreased range of motion secondary to intra-articular blood and accompanying muscle spasm. There is usually a fever and elevated white cell count, raising the differential diagnosis of a septic arthritis. Joint aspiration, urgent Gram’s stain, and culture and sensitivity are performed in this instance. The knee is most commonly affected, followed by the elbow, ankle, hip, and shoulder, in order of decreasing frequency. In the setting of recurrent bleeds, flexion contractures are likely to develop, especially in the knees and elbows. Not surprisingly, studies have repeatedly shown a poor correlation between physical examination and the extent of cartilaginous destruction demonstrated on MRI. Hemarthroses usually begin in the first two decades of life. Each bleeding episode usually involves a single joint (70% of episodes are monoarticular). Over the course of the patient’s lifetime, however, a few or several joints may be involved. The number of joints affected tends to stabilize by age 20. A hemophiliac pseudotumor occurs in 1 to 2% of hemophiliacs. This is a chronic posthemorrhagic cystic collection of encapsulated hemorrhagic fluid within muscle and bone characterized by pressure, necrosis, and destruction. Pseudotumors arise secondary to intraosseous or subperiosteal hemorrhage or less often within the medullary cavity, giving the appearance of an expansile lytic process. There are two distinct subtypes of pseudotumor, juvenile and adult forms. The juvenile form usually consists of multiple intramedullary expansile lesions without soft-tissue mass in the small bones of the hands or feet, occurring before epiphyseal closure. The adult form is usually a single intramedullary expansile lesion with a large soft-tissue mass in the ilium or femur. Soft-tissue involvement of the retroperitoneum, psoas muscle, bowel wall, or renal collecting system may be seen. These lesions are typically painless, expanding masses that may cause pressure on adjacent organs. Pseudotumors destroy soft tissue, erode bone, and cause neurovascular compromise and are most commonly found in the femur, pelvis, and tibia. They are usually asymptomatic until there is a pathologic fracture. Radiographic findings vary according to the stage of the disease. Arnold and Hilgartner have proposed a five-stage classification, which has proven useful in the assessment of the bony changes:

Hemophilia

Clinical Presentation

Radiologic Findings

Diagnosis

Differential Diagnosis

Discussion

Background

Etiology

Pathophysiology

Clinical Findings

Stages of Disease

Complications

ARTHROPATHY AND OSTEOARTHRITIS

PSEUDOTUMOR

Pathology

GROSS

MICROSCOPIC

Imaging Findings

RADIOGRAPHY

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree