Axial T2WI at the level of corona radiata.

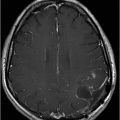

Axial SWI of the brain at the level of lateral ventricles and basal ganglia.

Sagittal GRE image.

Time of flight MRA of the circle of Willis.

Progressive Hemifacial Atrophy: Parry-Romberg Syndrome with Localized Scleroderma

Primary Diagnosis

Progressive hemifacial atrophy: Parry-Romberg syndrome with localized scleroderma

Differential Diagnoses

Hemifacial microsomia (Goldenhar syndrome)

Rasmussen encephalitis

Partial lipodystrophy (Barraquer-Simons syndrome)

Post-traumatic facial atrophy

Postradiation changes

Unilateral salivary gland and unilateral facial and masticatory muscle atrophy

Imaging Findings

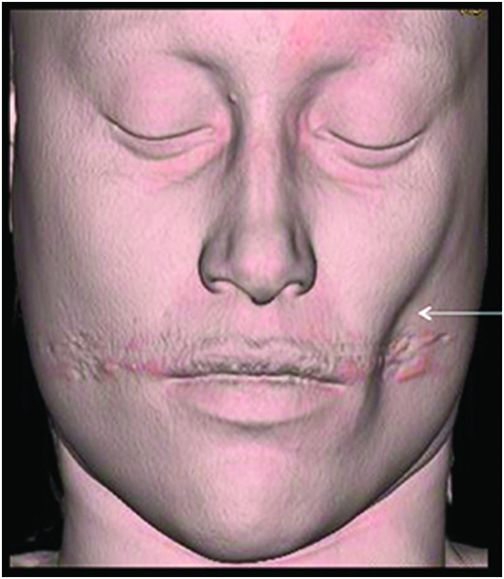

Fig. 134.1: Photographs show (A) left-sided facial scarring and asymmetry (arrows) and (B) focal alopecia. Fig. 134.2: Axial FLAIR MRI demonstrated white matter changes in the left frontal periventricular region (arrow) and focal thinning of the left frontal scalp tissues (arrow). Fig. 134.3: Axial T2WI at the same level also showed white matter changes (arrow). Fig. 134.4: Axial SWI and Fig. 134.5: Parasagittal MRI demonstrated multiple foci of blooming/T2 shortening in the left frontal lobe (arrows). Fig. 134.6: 3D surface rendering image depicts left facial atrophy as en coup de sabre. Fig. 134.7: MRA of the circle of Willis shows normal appearance.

Discussion

Unilateral hemifacial atrophy with involvement of skin, subcutaneous fat, muscle, bone, cartilage, and associated CNS findings on imaging as seen in this patient are classic findings of Parry-Romberg syndrome.

Although congenital hemifacial microsomia is a non-progressive developmental disorder involving the first and second branchial arches, it does not present with cutaneous pigmentation changes or thinning of the dermis. Parry-Romberg syndrome has been reported to have an association with Rasmussen encephalitis. Based only on imaging, the unilateral cerebral atrophy can cause difficulty in differentiating it from Rasmussen encephalitis. However, the clinical presentation along with predominant involvement of the subcutaneous fat, muscle, and other hemifacial structures is helpful in distinguishing between the two pathologies. Clinical history excludes post-traumatic atrophy and lack of craniofacial bone deformities on imaging is evident. Postradiation changes are asymmetric, but are usually bilateral, and correlation with lack of history of head and neck malignancy excludes them from the list of differential diagnoses. Partial lipodystrophy, also a bilateral condition, is limited to adipose tissues. Often, unilateral atrophy of the salivary glands and masticator muscles can mimic Parry-Romberg syndrome. However, the atrophy is localized to the gland or muscles with no obvious changes in the subcutaneous fat or underlying bones.

Parry-Romberg syndrome is a rare form of self-limiting but progressive hemifacial atrophy beginning in the first and second decades of life. It was first described by Parry in 1825 and Romberg in 1846. Parry-Romberg syndrome is characterized by slow but progressive unilateral facial atrophy resulting in facial asymmetry. The process involves the skin, subcutaneous tissues, muscles, cartilage, and bones. Prevalence is at least 1 in 700,000 in the general population, with a slight female preponderance.

The average age of onset is around 10 years of age. The skin can be tense, dry, and hyper- or hypopigmented. A demarcation line, or cleft near the facial midline, may occasionally be identified between the normal and the abnormal skin, giving a coup de sabre appearance. A variety of ocular changes has also been reported, the most common being enophthalmos due to loss of intraorbital fat. Other symptoms include heterochromia, globe retraction, and uveitis. Hair depigmentation or alopecia; smaller ipsilateral ear; lip, tongue, and salivary gland atrophy; dental abnormalities; and osseus defects can also be present. Neurologic symptoms are diverse and include seizures, trigeminal neuritis, and severe headache confined to the side of atrophy. There have even been isolated reports of associated hemibody atrophy. Symptoms typically progress slowly for up to 20 years and eventually stabilize.

The pathophysiology of Parry-Romberg syndrome remains unclear, although several hypotheses have been proposed. The most popular suppositions include autoimmunity and disturbance of fat metabolism related to a trophic malformation of the cervical sympathetic nervous system. Trauma, viral infection, hereditary, or endocrine disturbances have also been suggested. Although there have been conflicting theories about a correlation between scleroderma and Parry-Romberg syndrome, the literature mentions that localized scleroderma may be the preceding lesion of progressive hemifacial atrophy. Hence, scleroderma and Parry-Romberg syndrome have overlapping features and are thus a part of the same disease spectrum.

Findings of hemiatrophy are well seen with either CT or MR imaging of the face. Atrophy involves the skin, subcutaneous tissues, cartilage, and bones to varying degrees, but is limited by the midline, which is characteristic of the disease. While imaging of the brain can be normal, a wide spectrum of findings has also been described. They are usually ipsilateral, but can rarely be bilateral or contralateral. These findings include cerebral hemispheric atrophy with ventricular enlargement, intracranial calcifications, microhemorrhages, and focal infarcts of the corpus callosum. Non-specific focal or diffuse signal abnormalities in the gray or white matter can also be observed, as can meningocortical dysmorphism, characterized by thickening of the cortex and leptomeninges with leptomeningeal enhancement. Aneurysms and vascular malformations may also be present. Parry-Romberg syndrome is self-limited, and has no definitive curative therapy. Treatment aims at providing symptomatic relief and once the disease has stabilized, may include reconstructive surgery. Steroids, antiepileptic medications seizure control, and immunosuppressive therapies have been attempted with varying degrees of success.

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree