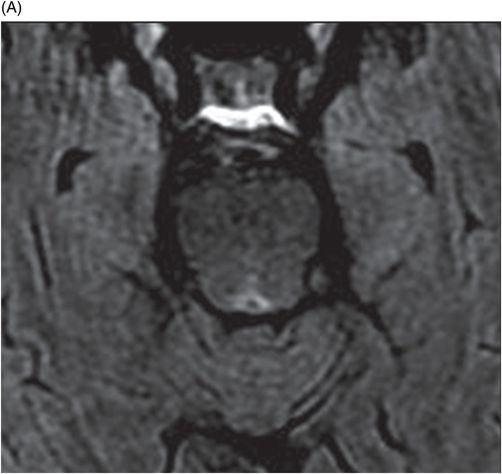

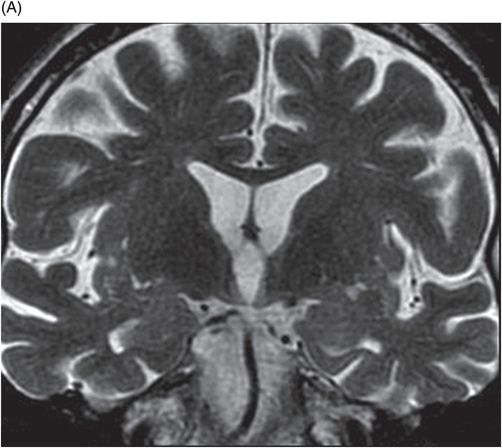

(A) Coronal T2 and (B) Axial FLAIR through the level of the third ventricle.

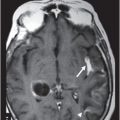

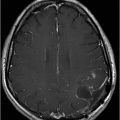

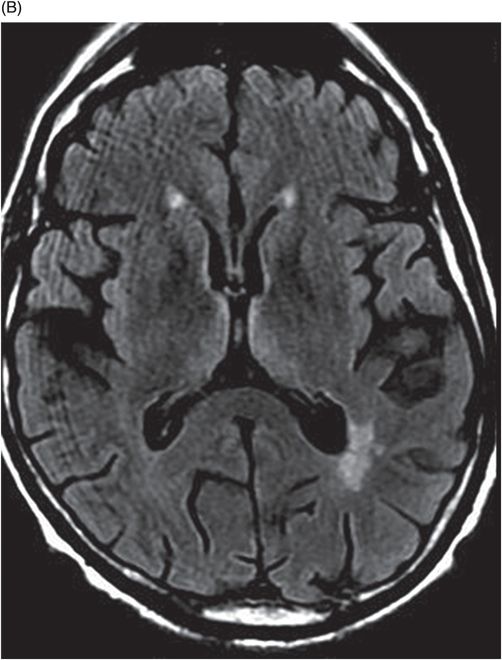

(A) Axial T1 postgadolinium and (B) Coronal T1 postgadolinium through the level of the cerebral peduncles and the third ventricle.

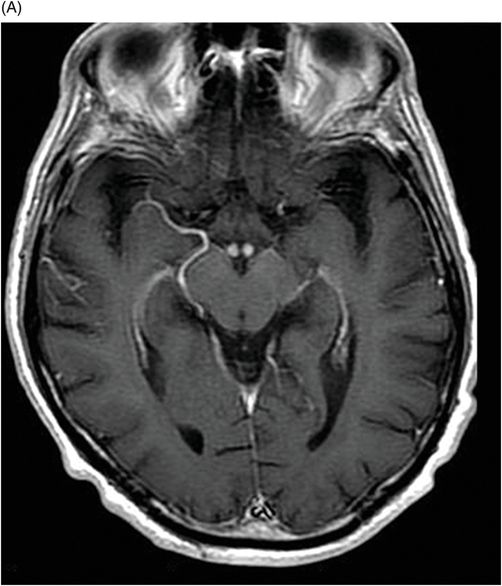

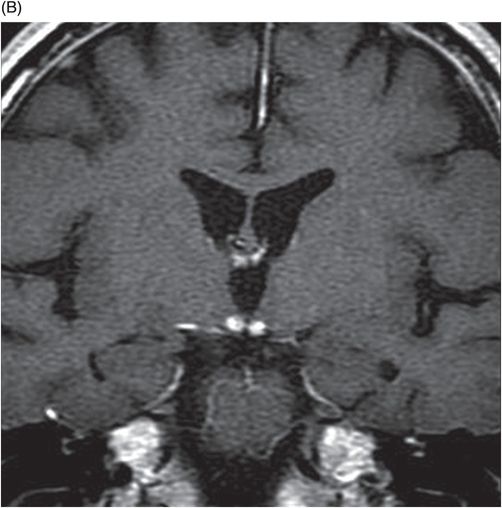

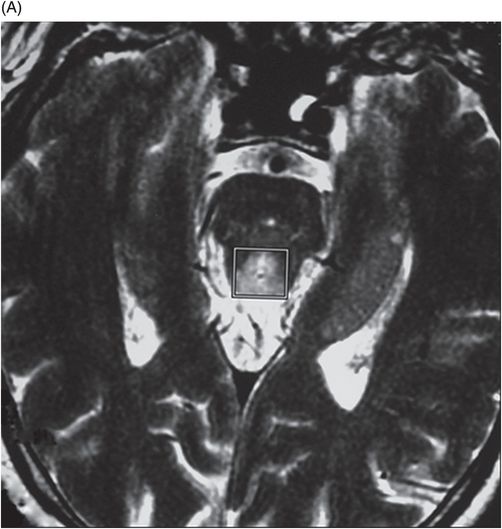

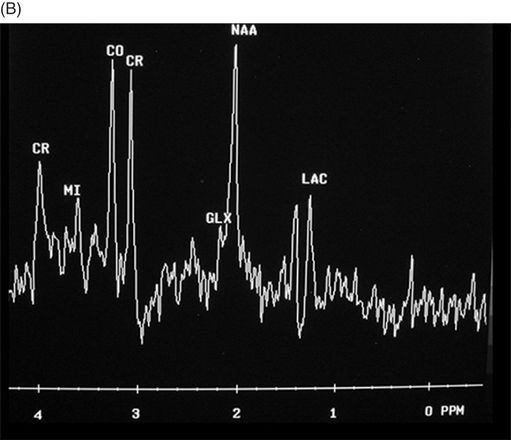

(A) Axial T2 and (B) Spectroscopy through the level of the Sylvius aqueduct.

Wernicke Encephalopathy

Primary Diagnosis

Wernicke encephalopathy

Differential Diagnoses

Ischemia of the artery of Percheron

Deep cerebral vein thrombosis

Acute disseminated encephalomyelitis

Variant Creutzfeldt-Jakob disease

Cytomegalovirus encephalitis

Imaging Findings

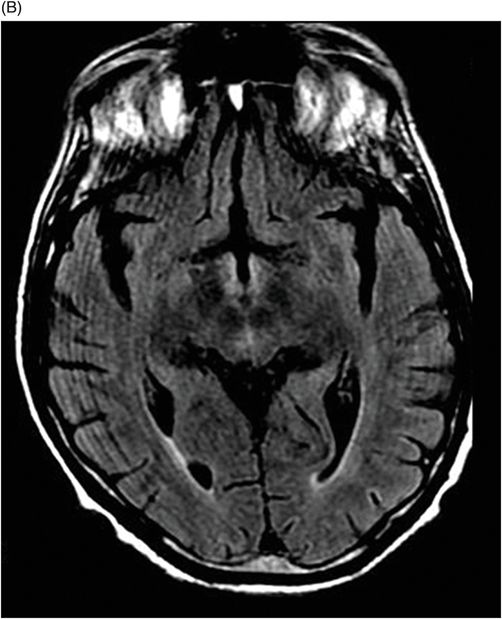

Fig. 78.1: In the enhanced CT study, there was an evident enhancement of both mammillary bodies. Fig. 78.2: (A) Axial FLAIR sequence at the level of the thalami showed bilateral and symmetric hyperintensity involving the peri-third ventricular medial thalami. (B) Axial FLAIR sequence at the level of the midbrain showed symmetric involvement of the periaqueductal gray matter of the midbrain as well. Fig. 78.3: (A–B) T2-FLAIR sequence demonstrated hyperintensity adjacent to the third ventricle. Fig. 78.4: (A) Axial TI and (B) Coronal T1 postgadolinium MR images demonstrated enhancement of the mammillary bodies. Fig. 78.5: MR spectroscopy of another patient with the same disease showed a lactate peak on the periaqueductal matter.

Discussion

In a patient with a history of alcohol abuse presenting with neurologic manifestations including altered mental status and ataxia, imaging findings demonstrating alterations in the median thalami and periventricular regions of the third ventricle are suggestive of Wernicke encephalopathy (WE), although these imaging findings are usually found in association with other typical alterations of WE. However, in rare cases, these alterations represent the only findings of WE and the differential diagnosis should include ischemic events encephalomyelitis, cytomegalovirus encephalitis, primary cerebral lymphoma, variant Creutzfeldt-Jakob disease (vCJD), and several viral infections. Wernicke encephalopathy should be considered for every patient with decreased consciousness that arrives to the emergency room.

In this patient, no restricted diffusion was demonstrated on imaging studies that would suggest an ischemic event. In addition, no signs of deep venous sinus thrombosis were noted, excluding a thrombotic event. Patients with acute disseminated encephalomyelitis (ADEM) usually have a prior history of viral infection or recent vaccination and are typically children or adolescents. The gray matter, especially the basal ganglia, is frequently involved; however, unlike typical WE findings, in ADEM there is also involvement of subcortical locations and lesions demonstrate ring-like (usually incomplete) enhancement.

Variant Creutzfeldt-Jakob disease is characterized by rapidly progressive dementia, sensory and psychiatric symptoms, with cerebral atrophy, myoclonus followed by death. Basal ganglia, especially the putamen and caudate, are involved. Patients with vCJD demonstrate characteristic hockey stick and pulvinar sign. In cytomegalovirus encephalitis, usually there are T2WI hyperintense lesions in the white matter that are most evident in a periventricular distribution. Enhancement is rare and can be seen in the ependymal surface when ventriculitis is present. Enhancement of the mammillary bodies after gadolinium administration is relatively specific to WE and is not a common finding of the differential diagnoses mentioned above.

Wernicke encephalopathy is an acute neurologic emergency due to thiamine (vitamin B1) deficiency. However, the disease may not manifest in all patients with thiamine deficiency because of a genetic susceptibility found in some patients who develop WE. Moreover, blood serum levels of thiamine may not be reduced at the time of clinical onset, and replacement of the vitamin does not always fully reverse the clinical picture, limiting the value of testing thiamine levels under certain circumstances.

Wernicke encephalopathy is commonly associated with chronic alcohol abuse, but may be related to hyperemesis gravidarum, anorexia nervosa, prolonged fasting/hunger strike, psychogenic food refusal, use of infant formula that does not contain thiamine, bariatric surgery, gastrectomy, malignant tumors of the gastrointestinal tract, prolonged intravenous feeding, and refeeding (orally or intravenously) after starvation without providing thiamine.

The classic triad of WE is ophthalmoplegia, ataxia, and confusion, but is only found in a minority of all patients with WE. Korsakoff syndrome may also present, occurring during the chronic stage of untreated WE. Korsakoff syndrome is characterized by neurologic signs of anterograde amnesia, impaired temporal order recall, confabulation, impaired recognition, loss of insight, and retrograde amnesia. Involvement of the brainstem segments of cranial nerves III, IV, and/or VI causes the ophthalmoplegia. Ataxia is seen secondary to involvement of the superior cerebellar vermis and brainstem segments of the vestibular nerve. Amnestic symptom and confusion are probably associated with involvement of the medial thalami and the mammillary body.

The pathologic findings in WE are usually represented by edema, spongy degeneration of the neuropil, neuron sparing, swelling of capillary endothelial cells, and extravasation of red blood cells. Typically, neuropathologic and neuroimaging lesions of WE are located in the peri-midline, in both periventricular and periaqueductal sites, in which there is abundant thiamine-related glucose and oxidative metabolism – most susceptible to thiamine deficiency. Magnetic resonance imaging studies of the most commonly involved WE sites, including the peri-third ventricular medial thalami, the periaqueductal gray matter of the midbrain, the peri-fourth ventricular pons and cerebellar vermis, and the peri-midline mammillary bodies, may permit accurate imaging diagnosis of WE. Signal intensity alterations in the cerebellum, cerebellar vermis, cranial nerve nuclei, red nuclei, dentate nuclei, caudate nuclei, splenium, and cerebral cortex represent atypical MRI findings in patients with WE.

In the acute stage of WE, involved sites demonstrate hyperintense signal on T2 and FLAIR sequences, variable enhancement after intravenous administration of gadolinium, and variable restricted diffusion. On CT studies, these sites can be hypodense; however, the sensitivity of this finding is very low. Areas with restricted diffusion in the setting of acute WE do not indicate irreversible cytotoxic edema and may be salvageable if treated promptly with thiamine.

Brain images of alcoholic patients with WE during the acute phase of the disease can be different from those of non-alcoholic patients. In patients with alcoholism, atrophy of the mammillary bodies, infratentorial regions, supratentorial cortex, and corpus callosum may be found in association with the alterations typical of WE. These abnormalities may be due to previous subclinical episodes. Contrast enhancement, particularly of the mammillary bodies, is more common in alcoholic WE patients than in non-alcoholic WE patients.

In follow-up studies, variable imaging findings will be noted, depending on when the diagnosis of WE was established and when thiamine was administered. Patients with complete clinical resolution typically show complete resolution of imaging findings. The other end of the spectrum can also occur, with diffuse atrophy and parenchymal loss in patients with significant clinical abnormalities. In most patients, imaging findings are between these extremities, with variable atrophy, and resolution of abnormal signal, abnormal enhancement, and restricted diffusion.

There is very little information about MR spectroscopy in WE. Low levels of NAA/creatine in the thalami during the acute stage of the disease with complete resolution after treatment can occur. Abnormal lactate peak levels may be found in some patients whose outcomes may range from complete resolution following treatment to chronic parenchyma loss.

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree