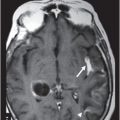

Axial postcontrast T1WI through the posterior fossa at the level of cerebellopontine angle cisterns.

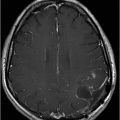

Axial T2WI through the posterior fossa at the level of cerebellopontine angle cisterns (follow-up).

Axial postcontrast T1WI at the level of nasopharynx and maxillary sinuses (follow-up).

Coronal T2WI at the level of sphenoid sinus and anterior temporal lobes.

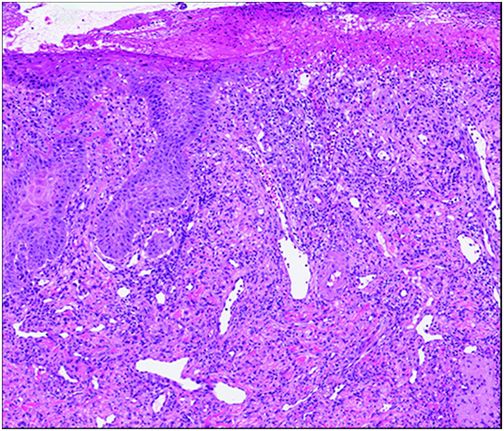

Histopathology of the right nasal ala biopsy.

Trigeminal Trophic Syndrome

Primary Diagnosis

Trigeminal trophic syndrome

Differential Diagnoses

Infectious etiologies: herpes, syphilis, or Mycobacterium leprae

Neoplasms: basal cell carcinoma, squamous cell carcinoma, or lymphoma

Autoimmune disorders: granulomatosis with polyangiitis

Imaging Findings

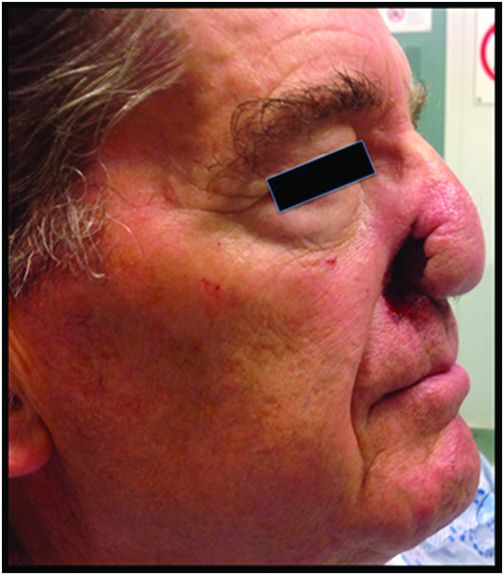

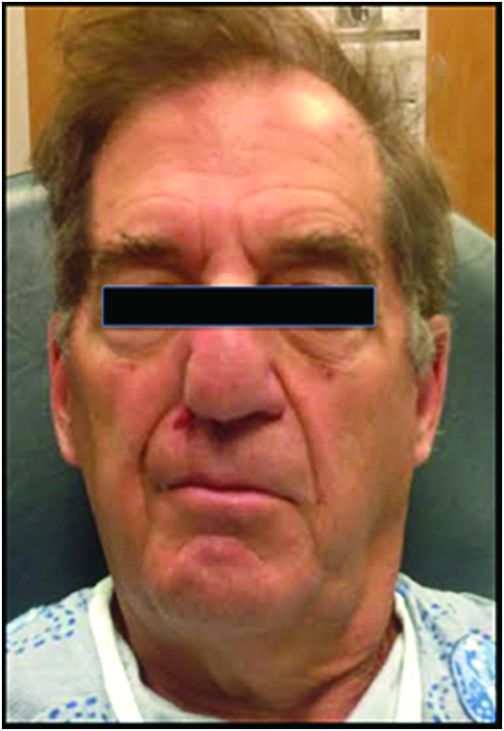

Fig. 136.1: Axial T1W postgadolinium image (preoperative) showed a homogeneously enhancing, extra-axial, right cerebellopontine angle cistern that was consistent with meningioma. Fig. 136.2: Axial T2WI at the level of cerebellopontine angle cistern (postoperative follow-up) showed significant encephalomalacic changes in the right hemipons, especially along the trajectory of the right trigeminal nucleus. Fig. 136.3: Axial postcontrast T1WI at the level of nasopharynx and maxillary sinuses demonstrated abnormal thickening and enhancement along the right nasal ala (arrow). Fig. 136.4: Axial postcontrast T1WI at the level of nasopharynx and maxillary sinuses showed subsequent ulceration and focal defect (arrow) (follow-up) and sparing of the nasal tip. Fig. 136.5: Axial T1WI at the level of nasopharynx and maxillary sinuses demonstrated diffuse atrophy of the muscles of mastication (temporalis, masseter, and pterygoid muscles) (arrows). Fig. 136.6: Coronal T2WI at the level of sphenoid sinus and anterior temporal lobes also showed diffuse muscle atrophy (arrows). Fig. 136.7: Facial profile image of the patient at presentation showed nasal ulceration. Fig. 136.8: Frontal facial image demonstrated facial asymmetry. Fig. 136.9: Punch biopsy of nasolabial fold demonstrated ulcerated squamous epithelium with underlying inflamed granulation tissue and reactive fibrosis. No evidence of invasive carcinoma or vasculitis was noted.

Discussion

Trigeminal trophic syndrome (TTS), also referred to as trigeminal trophic ulceration, is a rare entity associated with damage to the central or peripheral trigeminal nerve pathway. The etiologies of trigeminal nerve damage leading to TTS include treatment for trigeminal neuralgia (such as alcohol injection of the Gasserian ganglion), tumors (meningioma, schwannoma, and astrocytoma), infectious processes (herpes, syphilis, and leprosy), cerebrovascular accidents, syringobulbia, and trauma. The characteristic triad of anesthesia, paresthesia, and nasal ala ulceration with sparing of the nasal tip in this patient confirms the diagnosis of TTS.

The onset of disease in TTS varies, ranging from weeks to decades following damage to the trigeminal nerve pathway. The incidence of TTS is unknown; however, there is an increased predominance among females (female-to-male ratio of 2.2:1) in the sixth decade of life. The mechanism of ulceration is thought to be due to repetitive self-mutilation in an attempt to relieve the paresthesias experienced by the patient following trigeminal nerve injury. The ulcers are frequently unilateral (the right side is affected two times more commonly than the left side), crescent-shaped, and involve the nasal ala. Ulceration can also involve the forehead, cheek, jaw, and ear and is referred to as ulceration en arc because it distinctly spares the nose tip, which can be involved in malignancies and other granulomatous infections.

On MRI, TTS manifests as soft tissue defects involving the nasal ala. Importantly, the nasal tip is spared owing to innervation of the nose tip by the medial nasal branch of the anterior ethmoidal nerve. Furthermore, there is no associated mass lesion to suggest neoplasm. Diffuse volume loss of the ipsilateral muscles of mastication in the distribution of the trigeminal nerve is noted. Remote skull base or intracranial surgeries can cause damage to the trigeminal nerve pathway and can be visualized along the trajectory of the trigeminal nucleus in the brainstem or along its course in the prepontine cistern and Meckel cave.

The ulceration associated with TTS demonstrates non-specific histology with signs of chronic trauma including lichenification, scarring, and pseudoepitheliomatous hyperplasia. The ulcerative lesion has a non-specific appearance; however, microbiology and histopathology serve as a valuable tool in excluding infectious-inflammatory and neoplastic entities. The diagnosis of TTS is often challenging and requires close clinical and radio-pathologic correlation. A comprehensive laboratory workup is essential in order to exclude neoplastic, autoimmune, or infectious etiologies.

Treatment of TTS is often challenging. Medications are used to reduce paresthesias (carbamazepine, vitamin B, diazepam, and amitriptyline). Dressings, occlusion masks, and cotton gloves can also be implemented to reduce repeated trauma to the affected area. Antibiotics are also frequently required to prevent against infection. Psychologic management is critical to educating the patient that the ulceration is self-induced via manipulation and digital picking. Transcutaneous electrical nerve stimulation has been described to improved blood supply and wound healing. Reconstructive surgery with regional flaps has been successfully utilized to correct cosmetic defects. Unfortunately, despite the varied treatment modalities the ulceration typically recurs.

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree