Axial non-contrast CT image at the level of middle cerebellar peduncles and pons.

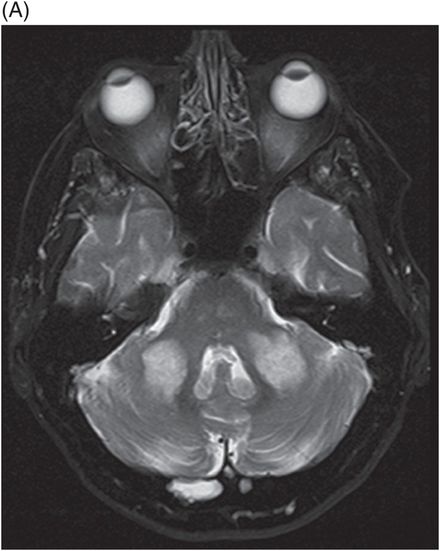

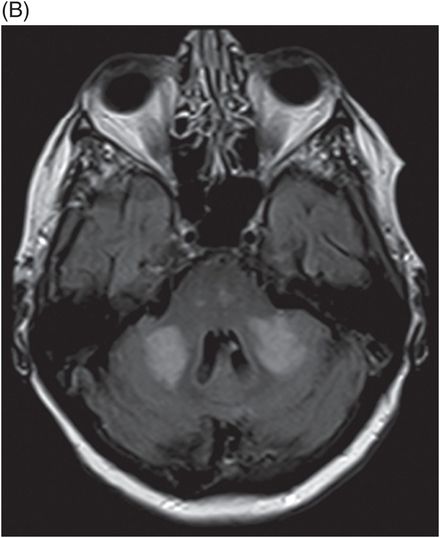

(A) Axial T2WI and (B) FLAIR at the level of middle cerebellar peduncles and pons.

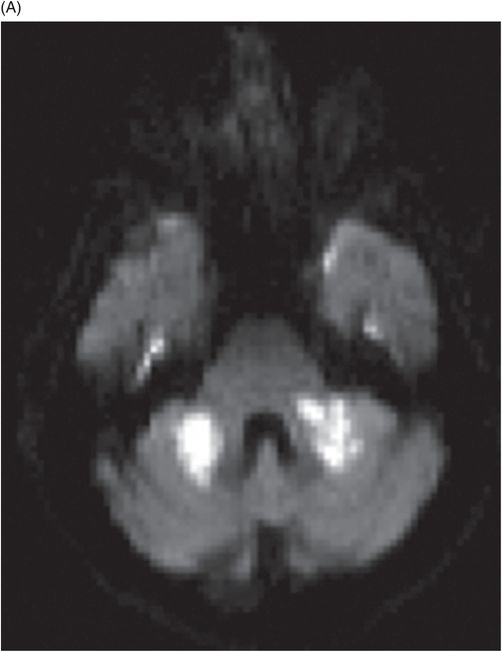

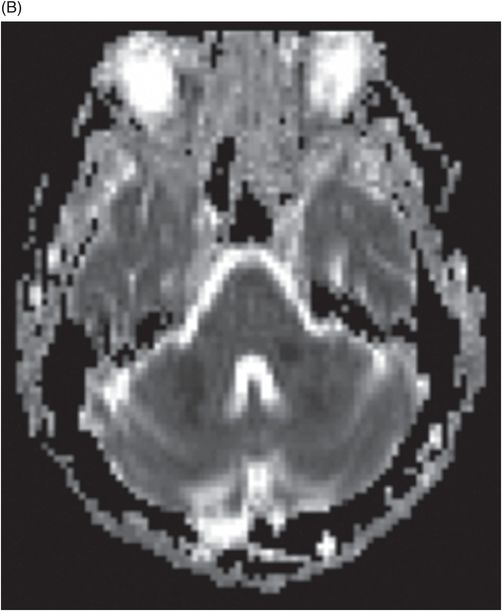

(A) Axial DWI and (B) ADC image at the level of middle cerebellar peduncles and pons.

(A) Time of flight MRA of circle of Willis and (B) carotids.

Bilateral Middle Cerebellar Peduncle Infarcts

Primary Diagnosis

Bilateral middle cerebellar peduncle infarcts

Differential Diagnoses

Demyelinating, infectious-inflammatory pathologies: multiple sclerosis (MS), acute disseminated encephalomyelitis (ADEM), progressive multifocal leukoencephalopathy (PML), or HIV

Metabolic conditions: Wilson disease, adrenoleukodystrophy, or adrenomyeloneuropathy

Neurodegenerative diseases: MSA-C, SCA-3, SCA-6, or DRPLA

Wallerian degeneration

Hypertensive encephalopathy

Imaging Findings

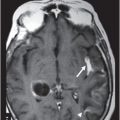

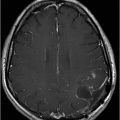

Fig. 137.1: Axial non-contrast CT demonstrates focal hypodensities involving the bilateral middle cerebellar peduncles. Fig. 137.2: (A) Axial T2WI and (B) FLAIR through the same level confirms the presence of hyperintense lesions. Fig. 137.3: Axial T1WI postgadolinium does not demonstrate enhancement. Fig. 137.4: (A) Axial DWI showed diffusion restriction with corresponding changes on (B) Corresponding ADC map. Fig. 137.5: Axial GRE image does not indicate presence of hemorrhage. Fig. 137.6: (A) MRA of the circle of Willis and neck vessels shows diffuse irregularity in the intracranial vertebral arteries. (B) MRA demonstrates atherosclerotic narrowing that impairs visualization of the extracranial segments. Significant atherosclerotic narrowing of both common carotid bifurcations is also noted.

Discussion

Demonstration of T2-FLAIR hyperintense signal and diffusion restriction in the bilateral middle cerebellar peduncles (MCPs) of a patient with sudden-onset vertigo and cerebellar neurologic deficits are classic features of acute ischemic changes involving the bilateral AICA (anterior inferior cerebellar artery) territories.

Demyelinating pathologies such as MS, ADEM, and infectious etiologies such as HIV and PML are known to present with bilateral MCP T2 and FLAIR hyperintense signal changes. Demyelinating lesions also tend to have supratentorial white matter and spinal cord changes. HIV and PML can have similar imaging features and are associated with volume loss and white matter lesions in the rest of the brain parenchyma. In PML, the pattern of diffusion restriction is along the periphery and represents the zone of demyelination. The sudden onset of symptoms, lack of white matter changes, and pattern of diffusion restriction in a patient with a negative HIV status make demyelinating or infectious etiologies unlikely diagnoses.

Several metabolic conditions such as Wilson disease, adrenomyeloneuropathy-adrenoleukodystrophy, and chronic liver disease can present with similar T2-FLAIR signal changes. Given the clinical presentation, these metabolic conditions are remote diagnostic options. Patients with acute hypoglycemia can present with similar T2-FLAIR and diffusion restriction signal; however, hematologic studies did not indicate hypoglycemia. Reversing the hypoglycemic status results in an improvement in clinical symptoms and MRI findings. In our patient’s case, her glycemic status was normal and symptoms persisted.

Hypertensive encephalopathy due to uncontrolled blood pressure can present with headache, visual symptoms, and altered mental status. The white matter changes are identical to PRES (posterior reversible encephalopathy syndrome) and represent areas of vasogenic edema. The brainstem, thalami, basal ganglia, and cerebral white matter are also involved. Abnormal T2-FLAIR hyperintense signal and DWI changes can also be seen in cases of paramedian pontomesencephalic infarctions, secondary to Wallerian degeneration, and often develop as early as 10–12 days following an ischemic event. A normal brainstem on imaging, as in our case, makes this entity less likely. Neurodegenerative conditions such as MSA-C (multiple system atrophy), various types of spinocerebellar ataxias (types 3 and 6), and dentatorubropallidoluysian atrophy (DRPLA) can have similar T2 and FLAIR signal changes but with associated cerebellar and brachium pontis volume loss. The clinical presentation is long-standing with progressive symptoms. The acute presentation also makes the possibility of tumors such as glioma and lymphoma very unlikely. Tumoral pathologies are often asymmetric, associated with mass effect, and progressive symptoms.

The MCPs derive their blood supply predominantly from the AICA with a smaller contribution from the superior cerebellar artery (SCA). The AICA supplies the anterolateral parts of the cerebellum including most of the MCPs, middle and lower lateral pontine region, flocculus, and anterior aspect of the cerebellar lobules. Infarcts of the MCPs are very rare and overall, unilateral infarcts comprise about 0.9–0.12% of acute strokes. Bilateral MCP infarcts are extremely rare and very few case reports of isolated infarcts have been documented in the literature. Most infarcts are known to occur involving the watershed zone of AICA and SCA territories. Patients often present with vertigo, horizontal nystagmus, auditory and speech disturbances, and ataxia in all four limbs. Hypoperfusion of the watershed zone has been proposed as the cause of infarcts. Trauma and dissection are other mechanisms that can cause bilateral MCP infarcts in cases with unusual anatomic vascular variants. Atherosclerotic occlusion of the bilateral extracranial-intracranial vertebral arteries has been described in most of the case reports causing hypoperfusion.

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree