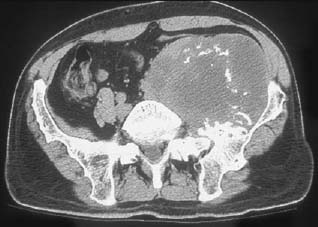

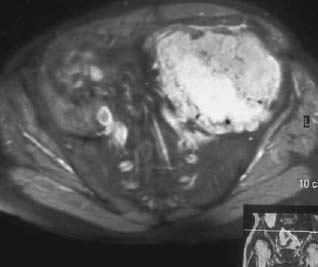

CASE 37 George Nomikos, Brian Edward Reeves, Anthony G. Ryan, A 39-year-old man experienced increasing fullness and pain in his left lower quadrant and left groin. He has a family history of bone tumors. Figure 37A Figure 37B Figure 37C Figure 37D The radiograph of the pelvis (Fig. 37A) shows marked deformity of the proximal femora bilaterally. There is undertubulation of the femora (Erlenmeyer flask deformities), as well as multiple osseous excrescences arising from the femora. These osseous excrescences demonstrate cortical and medullary continuity with the underlying bone and are consistent with multiple osteochondromas. Multiple smaller lesions are identified in the pelvis as well. In addition, there is an area of osseous destruction involving the left periacetabular region. The CT (Fig. 37B) shows a large mass arising from an osteochondroma involving the left iliac wing. The lesion demonstrates a chondroid pattern of internal mineralization. Note the low attenuation of the nonmineralized portions of the mass. This attenuation is due to the high water content of hyaline cartilage. Also note the multiple small osteochondromas on the pelvis, producing a “wavy” contour. The T1-weighted MRI (Fig. 37C) shows pelvic corticomedullary continuity between the osteochondromas and underlying bone. The large pelvis mass is also seen to be very low signal intensity on the T1-weighted image and high signal intensity on the T2-weighted image (Fig. 37D), again because of the high water content of the hyaline cartilage in the low-grade chondrosarcomatous degeneration. Hereditary multiple exostoses (familial osteochondromatosis or diaphyseal aclasia) with malignant transformation of one lesion into chondrosarcoma. None. Osteochondromas, which represent the most common tumor or tumorlike process of bone, may be solitary or multiple. Solitary lesions are much more common than multiple, with an estimated frequency in the general population of 1 to 2%. Lesions most frequently affect the knee, and the femur is the most commonly involved bone. Lesions may develop, however, in any bone that forms from enchondral ossification. These lesions arise from a fragment of physeal cartilage that separates from the growth plate and extrudes through the periosteal bone cuff encircling the growth plate (zone of Ranvier) into the cortex. This is thought to be related to the process of remodeling occurring in the “cutback” zone of long bones during their growth phase. By the process of enchondral ossification, this intracortical fragment of physeal cartilage develops into an osseous stalk (with cortical and medullary continuity with the underlying bone) with a cartilaginous cap that continues to grow until skeletal maturity is reached. The development of one or more exostoses with pathology identical to that of de novo osteochondromas has been associated with radiation therapy. These radiation-induced exostoses are usually seen in children who receive radiation between the ages of 8 months and 11 years, often for Wilms’ tumor, neuroblastoma, or rhabdomyosarcoma of the bladder, and tend to occur at the periphery of the radiation field. The mean time to development of an osteochondroma after radiation is ~3 to 17 years. Malignant transformation is rare. The most common symptom for a solitary osteochondroma is a painless mass causing an aesthetic deformity. The lesions first appear in childhood as lumps near joints and may produce pain in children if traumatized. The lesions may also compress adjacent nerves and tendons or cause mechanical problems if they grow large enough to impede joint mobility. Hereditary multiple exostoses (HME) is a familial disorder with autosomal dominant inheritance, secondary to genetic abnormalities involving chromosomes 8, 11, and 19. Cases infrequently arise spontaneously. Because of more severe deformities, diagnosis is usually made early in life (usually by age 5 and rarely after age 12). There is incomplete penetrance in females. People with diaphyseal aclasia may be shorter than average or have bowed extremities, as the proximity of the exostoses to the growth centers can interfere with epiphyseal growth.

Diaphyseal Aclasia

Peter L. Munk, Thomas Pope, and Mark Murphey

Clinical Presentation

Radiologic Findings

Diagnosis

Differential Diagnosis

Discussion

Background

Etiology

Clinical Findings

Complications

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree