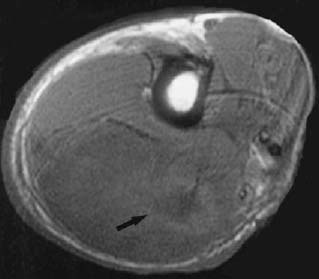

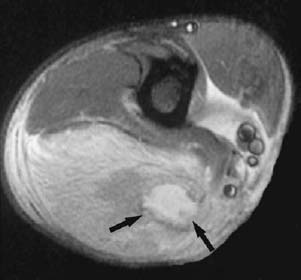

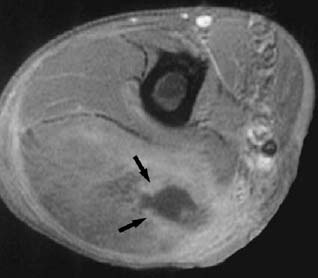

CASE 75 Sam Y. Chun, Ali Islam, Alison Spouge, Anthony G. Ryan, and Peter L. Munk A 40-year-old diabetic patient presented with sudden onset of arm pain, swelling, and erythema. The patient was afebrile with a normal leukocyte count. Figure 75A Figure 75B Figure 75C An axial spin-echo T1-weighted image (Fig. 75A) shows diffuse low signal intensity within the triceps muscle, with a more focal region of hypointensity (arrow). Extensive high signal intensity is present on the inversion recovery sequence (Fig. 75B), with a focus of particularly high intensity (arrows) corresponding to the hypointense region on the T1 image. Fat-saturated T1-weighted image postgadolinium (Fig. 75C) shows rim enhancement of the area consistent with abscess formation (arrows). Pyomyositis. Diagnosis of soft-tissue infections has markedly improved with the advances in cross-sectional imaging modalities, particularly MRI. Soft-tissue infections can be generally classified as Here we will focus on primary soft-tissue infections, that is, cellulitis, necrotizing fasciitis, and pyogenic myositis (pyomyositis). Group A Streptococcus is the most common causative organism, followed by Staphylococcus aureus. Other inciting organisms include Haemophilus influenzae, Streptococcus pneumoniae, Neisseria meningitidis, and Cryptococcus. Although the majority of cases are polymicrobial, group A Streptococcus and/or S. aureus are commonly the initial infecting bacteria. Other aerobic and anaerobic organisms may be present, including Bacteroides, Clostridium, Peptostreptococcus, Enterobacteriaceae, coliforms, Proteus, Pseudomonas, and Klebsiella. Infectious myositis can be caused by a variety of pathogens, including bacteria, viruses (e.g., influenza, coxsackie), protozoa, and parasites. Pyogenic myositis is most frequently caused by Staphylococcus aureus; less common causative bacteria include Mycobacterium tuberculosis, Nocardia, Streptococcus pyogenes and viridans, and Cryptococcus. Cellulitis generally refers to an acute spreading infection of the dermis and subcutaneous tissues that presents with signs and symptoms of inflammation (pain, swelling, erythema, and heat). Other clinical findings may include regional lymphadenopathy and fever. If the cellulitis becomes more extensive or spreads to other structures, complications such as necrotizing fasciitis, osteomyelitis, and septic arthritis may arise. Aspiration of the wound is rarely useful, as the cultures are positive only one third of the time. Necrotizing fasciitis is a relatively rare but rapidly progressive condition, with an associated mortality rate of 30 to 70%. It is characterized by extensive necrosis of the subcutaneous tissues, fascia, and surrounding soft tissue. Predisposing risk factors include immunocompromised conditions such as diabetes, cancer, and vascular disease. There is often a history of recent trauma or surgery to the involved area. Necrotizing fasciitis in its early stages may be difficult to diagnose, as patients may have a nonspecific presentation of pain, swelling, and fever. The clinician should be suspicious of this condition in patients whose pain is out of proportion with physical signs. The infection can spread rapidly over the course of hours or days as a growing area of indurated, erythematous skin that eventually becomes a dusky or purplish color. The pain may progress to anesthesia due to necrosis of nerve fibers. The most important physical findings include tissue necrosis, putrid discharge, bullae and blisters, severe pain, crepitus, rapid undermining of the fascial planes, and relative lack of the classical inflammatory signs. The degree of deep-tissue necrosis is usually more severe than clinical findings suggest. The patient may rapidly progress to septic shock and multiorgan failure.

Cellulitis

Clinical Presentation

Radiologic Findings

Diagnosis

Differential Diagnosis

Discussion

Background

Etiology

CELLULITIS

NECROTIZING FASCIITIS

PYOMYOSITIS

Clinical Findings

CELLULITIS

NECROTIZING FASCIITIS

PYOMYOSITIS

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree