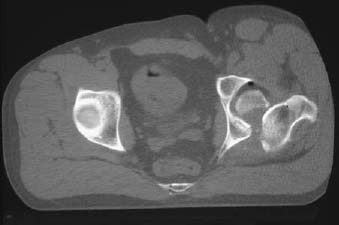

CASE 95 Anthony G. Ryan and Peter L. Munk A 27-year-old man, traveling in the passenger seat of a car involved in a high-speed collision, presented with severe left-sided hip pain and an inability to move his left leg. An initial diagnosis of a posterior dislocation of the left hip was made, and closed reduction was performed emergently. Figure 95A Figure 95B Figure 95C A coned anteroposterior (AP) radiograph of the left hip (Fig. 95A) shows a large crescentic radio-density projected through the inferomedial half of the femoral head, which appears appropriately enlocated within the acetabulum. The presence of the large free fragment prompted a decision to proceed to open reduction and internal fixation (ORIF), and radiology was consulted for a preoperative CT. A single slice from the CT (Fig. 95B) shows not only the large free fragment within the left hip joint but also that, despite the plain film appearances, the femoral head remains dislocated, necessitating formal relocation of the femoral head prior to reducing and fixating the large free fragment. A bubble of free nitrogen at the least dependent portion of the hip joint is evident, as is a subtle contained fluid-fluid level, the latter representing an intra-articular lipohemarthrosis. An AP radiograph of the subsequently relocated hip joint and fixated Pipkin fracture with 4.0-mm cancellous screws is shown in Fig. 95C. Hip dislocation complicated by Pipkin fracture and failed initial closed reduction, necessitating open reduction and fixation. None. Given the relative bony security of the joint, hip dislocation is uncommon, accounting for only 5% of all dislocations. Eighty to 85% of hip dislocations occur posteriorly (Figs. 95A–95E). Posterior dislocations may be classified as two subtypes: those with and those without an accompanying fracture. The most common associated fracture is a single large fracture of the posterior acetabular rim, followed, in decreasing order of occurrence, by a comminuted fracture of the acetabular rim (Fig. 99F), a fracture of the acetabular rim and floor, and a fracture of the femoral head. Having passed through the sciatic notch, the femoral head usually occupies a position on the dorsum of the ilium. Anterior dislocation occurs in about 5 to 10% of cases. The femoral head is displaced medially and toward the obturator foramen, pubis, or ilium. Anterior dislocations are further divided into superior and inferior subtypes: inferior dislocation occurring toward the obturator foramen and superior dislocation occurring toward the anterior superior iliac spine. There are two major types: the anterior obturator dislocation and the superoanterior pubic hip dislocation. Central (internal) acetabular fracture dislocation refers to the head of the femur being driven medially, fracturing the acetabulum, and consequently protruding into the pelvic cavity secondary to an impact to the lateral side of the greater trochanter. There is thus an invariable accompanying acetabular fracture. Rarely, luxatio erecta of the hip joint may occur, whereby traumatic hip dislocation results in inferior dislocation of the femoral head and inversion of the femoral shaft. The classic injury involves a passenger in a sudden deceleration motor vehicle accident where the knee is struck forcibly against the dashboard, pushing the hip joint out posteriorly. At the moment of impact, the affected leg is typically flexed and “crossed” over the midline. In this position, the femoral head is covered posteriorly only by capsule. The femoral head is driven posterolaterally and is maintained in a position superior to the level of the acetabulum by muscular contraction and spasm. The dislocation may occur on the job, for example, by a large weight landing on the back of a person leaning forward, whereby the femur remains stationary and the pelvis is pushed anteriorly. Figures 95D,95E An anteroposterior radiograph of the right hip (95D) shows clear dislocation of the right hip with superior displacement of the femoral head and femoral neck acetabular approximation. There is an associated comminuted fracture of the posterior acetabular margin and an associated fracture of the femoral head margin. Note the curvilinear density lateral to the femoral head. Although the above signs suggest a posterior direction of displacement, the subspinous location of the femoral head raises the possibility of an anterior dislocation. An additional Judet view (95E) was performed, confirming the direction of dislocation as posterior. An anterior injury may occur from a direct blow on the posterior aspect of the abducted and externally rotated thigh, as may occur secondary to a fall from a height or an impact with the leg in this position (pointing laterally) during a high-energy contact sport. The typical mechanism is a blow to the lateral aspect of the hip, usually secondary to road traffic accidents, and occasionally following a fall on the side, usually from a considerable height. When transient subluxation or dislocation with reduction has occurred, and there is no associated fracture, the pattern of associated muscle injury may be a useful secondary sign that such an injury has taken place. In transient subluxation or dislocation, there may be mechanical disruption of the blood supply to the femoral head. Hemarthrosis may also contribute to vascular impairment. These patients are thus at increased risk of osteonecrosis, chondrolysis, and secondary osteoarthritis. The incidence of osteonecrosis increases with the delay in reduction of a dislocated hip. Chondrolysis is manifest on plain films as loss of joint space, and both chondrolysis and osteonecrosis may be accurately detected with MRI. The forces required to dislocate the hip are rarely generated during sporting activities, and hip dislocations are consequently unusual. Transient subluxation or dislocation with spontaneous reduction may occur in contact sports, however. They may be considered a muscle strain initially, and the subluxation may go unrecognized, particularly if there is not an associated acetabular rim fracture.

Hip Dislocation

Clinical Presentation

Radiologic Findings

Diagnosis

Differential Diagnosis

Discussion

Background

Etiology

POSTERIOR DISLOCATION

ANTERIOR DISLOCATION

CENTRAL ACETABULAR FRACTURE DISLOCATION

TRANSIENT SUBLUXATION OR DISLOCATION WITH REDUCTION

Pathophysiology

Clinical Findings

POSTERIOR DISLOCATION

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree