Fig. 17.1

Niche/defect left behind by the previous CD. (a) Sagittal image of the niche marked by an arrow (Cx cervix). (b) Three-dimensional orthogonal images of the uterus showing the niche (arrows). The width of the dehiscence should always be looked at on a transverse or coronal view since that is the real size of it. Unenhanced images. (c, d) At times, the niche/dehiscence extends all the way from the uterine cavity to the anterior surface of the uterus. Saline infusion sonographic images

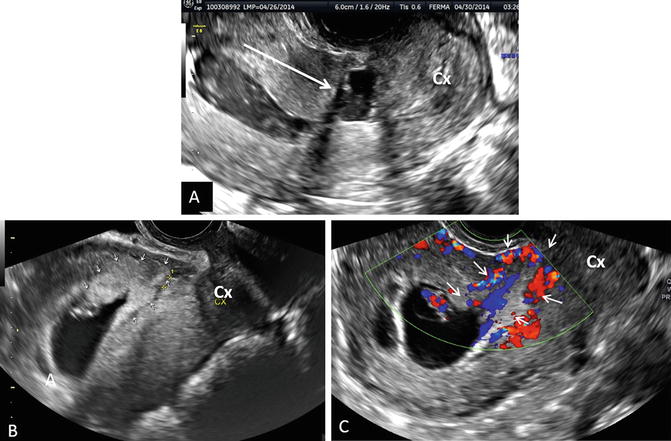

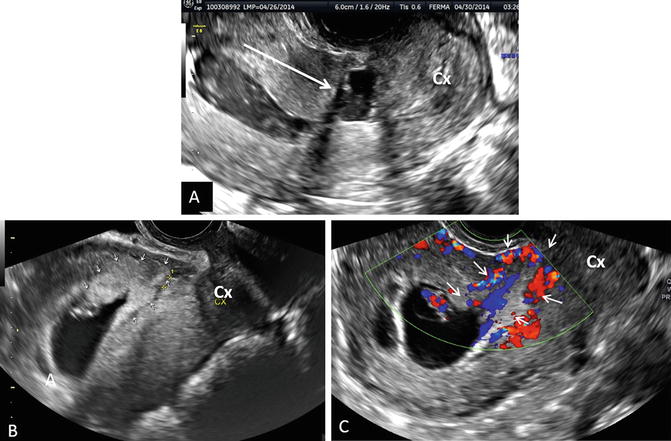

At times, the niche is deep and wide (Fig. 17.2a), explaining the deep insertion of the tiny placenta with its rich blood supply (see Fig. 17.2b, c). Since the prevalence of niches is relatively high, it can be expected that the possibility of such deep implantation is realistic; therefore, a careful scrutiny of the small placenta and its vessels should be performed in all first-trimester diagnoses of CSP.

Fig. 17.2

Placental implantation into the niche of a previous CD. Sagittal images (Cx cervix). (a) Saline infusion sonohysterography of a uterus with a large niche. (b) Gray scale sagittal image of a CSP. Note the implantation of the placenta in the niche outlined by small arrows. (c) Color Doppler image of the same CSP demonstrating the invasion of the placenta (outlined by small arrows) with its blood vessels into the myometrium

Incidence/Risk Factor

Estimated incidence rates of CSP range between 1/1800 and 1/2500 of all CDs performed [7–10]. Seow et al. [11] states that CSP was seen in 0.15 % of all pregnancies with a history of a previous CD. The above numbers appear unrealistic; however, their true incidence is unknown due to the lack of population based statistics (registries).

The only risk factor for CSP is a previous CD. However, since we found about eight cases of recurrent CSP in the literature, including our own case with four recurrences [12], we have to consider a previous CSP as a rare but possible risk factor for this entity.

Pathogenesis of CSP

Later in this chapter, we will provide evidence that the histology of the tiny placental insertion or myometrial invasion of a CSP in the first trimester of the gestation is identical with the histologic findings of a MAP in the second and third trimester of pregnancy. The only scientifically proven fact is that, in both diseases (CSP and MAP), intervening fibrinoid layer between the myometrium and the cytotrophoblastic shell in the placenta is naturally present between the endometrium in normally attached placentae when thinned or missing. This fibrin layer (fibrinoid material) is known by the name of Nitabuch layer. Previous uterine surgery or uterine interventions lead to thin or absent decidua basalis in scarred areas, as well as the abovementioned protective layer of the lower uterine segment. In CSP and in MAP this membrane is missing and the placental villi attach themselves and penetrate between the myometrial fibers into the depth of the uterine wall.

Other theories, such as the role of a low oxygen tension at the area of the scar providing a stimulus to help the invading cytotrophoblast [13, 14], as well as the in vitro studies of Kliman et al. [15] with trophoblast and EM explants, showing a strong propensity for attaching to exposed extracellular matrix and then to endometrial epithelial cells, are the most frequently quoted. Both theories support the observation that the more CDs a patient has, the higher risk of placenta previa and a MAP.

Diagnosis of CSP

The two diagnostic modalities used are ultrasound and MRI; however, ultrasound is the best modality. Transvaginal sonography (TVS) presents an advantage over transabdominal ultrasound (TAS), since it has a higher resolution and can be placed in close proximity to the low, anterior gestational sac. MRI has been used for imaging and is expensive. In addition, it requires moving the patient to a radiology site. Also, MRI lacks the color Doppler flow that provides a high resolution image, which is important in establishing a correct diagnosis.

The diagnosis of CSP requires a high clinical index of suspicion. We reiterate, that every woman with a history of a previous CD and a positive pregnancy test, presenting in the first trimester of the pregnancy, should be considered a “rule out CSP” until proven otherwise. Stirnemann et al. [16, 17] published studies to lay the basics for such screening if proven significant. Until that time, this should be strongly considered, since there is no downside to that first early scan. Godin et al. [18], Vial et al. [19], and Seow et al. [20] published similar sonographic criteria they used to define a CSP; however, other authors used additional characteristics, relying mostly on single cases.

Our diagnostic criteria of CSP [4, 21] took in consideration a history of previous CD, a positive pregnancy test and the following sonographic criteria (Fig. 17.3):

Fig. 17.3

Sonographic markers of CSP (Cx cervix, Bl bladder, UC uterine cavity). (a) Empty uterine cavity and cervical canal. Low anterior triangular gestational sac with yolk sac in close proximity to the bladder (long arrow). (b) Triangular gestational sac with close proximity to the bladder. (c) The developing vascularity between the sac and the bladder. (d) Arteriovenous malformation in a CSP that required UAE

Endometrial and endocervical canal devoid of a gestational sac;

Placenta and/or a gestational sac embedded on or in the hysterotomy scar/niche;

In early gestations, a triangular gestational sac that fills a niche of the scar (Fig. 17.4);

Fig. 17.4

Additional images of the shape of the early 4–6 week chorionic sac of the CSP (Cx cervix). (a) Flat sac. (b) Oval sac. (c) Triangular sac. (d) Square sac

Thin or absent myometrial layer between the gestational sac and the bladder;

The presence of a chorionic sac, with or without embryonic/fetal pole and/or yolk sac and with or without heart activity;

The presence of a prominent and at times rich vascular pattern at or in the area of a CD scar. As a rule, detection of peri-trophoblastic blood flow, detected by the most sensitive Doppler settings around a low, anteriorly situated chorionic sac, in a patient with a previous CD, is a reliable sign of CSP.

It is remarkable that, at very early stages of the pregnancy (4–5 weeks), the blood vessels tend to concentrate on the anterior side of the chorionic sac (Fig. 17.5) “marking” the site of the placental implantation.

Fig. 17.5

The developing vascular grid of the early CSP. (a, b) 2D color Doppler of the vessels surrounding the chorionic sac. (c) Three-dimensional, orthogonal planes and 3D rendering (lower right picture) of the vascularity that starts to concentrate on the anterior side of the sac, the future site of the placenta. We suspect that the future placenta will invade the myometrium in the anterior direction. (d) Thick-slice 3D rendering of the sac with its vessels clearly more prominent anteriorly

The usefulness of 3D ultrasound in the diagnosis is debated. However, it furnishes information regarding the exact location of the sac, its vascularity and volume, the latter two in a quantitative fashion (Fig. 17.6). We use the above measurements to follow the healing process of the treated cases or for the early warning signs of an impending arteriovenous malformation (AVM) developing at the treatment site.

Fig. 17.6

The use of 3D ultrasound in the diagnosis and follow-up of treatment of CSP. (a) 3D orthogonal planes with power Doppler used in segmentation (marking the perimeter of the sac) to obtain the volume of it. (b) After the volume of the sac is obtained a special algorithm is applied to compute and display the quantitative vessel content of the above volume. (c) Visual display of the 3D vascular angiogram that can be used qualitatively for follow-up purposes after local injection of UAE treatments

If an AVM was suspected (at times, this may be the presenting sonographic picture), Doppler measurements of the blood velocity were measured and expressed by the peak systolic velocity (PSV) in cm/s. Velocities above 39 cm/s were considered for uterine artery embolization (UAE) by the interventional radiologist. This evaluation is best done when the region of interest of the Doppler interrogation is constricted to the questionable area, using the appropriate pulse repetition frequency and filter settings.

These are pathological, high velocity, low resistance “short circuits” of the blood stream between an organ’s arterial and venous supply. Ultrasound presents a valuable tool for the diagnosis of AVM and guideline for their treatment [22]. Although uncommon, they may cause dangerous hemorrhages due to disrupted blood vessels, after miscarriage or uterine instrumentation [23]. The acquired form, seen in CSP, is usually traumatic, resulting from prior dilation and curettage (D&C), therapeutic abortion, uterine surgery, or direct uterine trauma. Their incidence is about 1 % of CSPs. In our series of 60 CSPs five, patients had AVM [24].

Differential Diagnosis of CSP

There are two main differential diagnostic entities to consider: First, a cervical pregnancy, which is rare and has no history of prior CDs. Second, a miscarriage in progress, which can be seen in the cervical canal or close to the internal os and “on its way out” having no heart activity. Also, under pressure on the cervix with the vaginal probe, the sac will slide back-and-forth, while a true CSP will stay fixed. It should be noted that misdiagnosis has, at times, severe consequences. The proof is in the literature: 107 of the 751 cases of CSP reviewed (13.6 %) were missed or misdiagnosed leading to complications (e.g., hysterectomy and loss of fertility) [4]. Figure 17.7 demonstrates a simple method to distinguish between the two, abovementioned, differential diagnostic entities and a true CSP.

Fig. 17.7

The simple algorithm to differentiate between an IUP and a CSP (or cervical pregnancy)

However, it is extremely important to realize that this simplified diagnostic aid is valid and reliable only while the gestational sac is small (e.g., 5–6 mm in diameter or 5–6 postmenstrual weeks) and remains “local,” close to the niche or above the scar. In other words, the sac did not start to elongate and move/expand cranially to fill the uterine cavity. In this case, the sac will be found increasingly in the uterine cavity misleading the uninitiated observer to think that it is an intrauterine sac. In such cases one should shift the attention from the sac and concentrate upon the blood vessels of the tiny placenta, which stay in their original site of implantation, thereby holding the most important diagnostic feature of CSP: the true site of placental implantation. Figures 17.2, 17.3, 17.4, and 17.5 clearly demonstrate the abovementioned diagnostic principle.

Lately, clinicians and clinical researchers have started to pay attention to the exact location of placental implantation in the area of the scar/niche left behind by the previous CD. Vial et al. [19] suggested that there are two kinds of CSPs, based on depth of implantation. The question is whether a deeply implanted chorionic sac in a niche or dehiscence, close to the bladder with very thin or no visible myometrium (Fig. 17.8a, b) will result in a worse outcome than if inserted on top of a scar that has some thickness (see Fig. 17.8c, d). Comstock et al. [25] and personal communication with Cali G. refer to “on-the-scar implantations” as “low lying sacs” and assume that these are the CSPs that may proceed to third trimester giving rise to MAP. Deeply implanted in the niche, surrounded by myometrium and seldom reach term is a “true” scar pregnancy. We slightly differ about the latter form of CSP since we have witnessed the reaching delivery of a live offspring.

Fig. 17.8

The issue of distance between the anterior uterine surface and the gestational sac: “in the niche/scar” or “on the scar” (Bl bladder). (a, b) These two are examples of a close proximity of the sac to the bladder (2.1 mm and 3.2 mm, respectively). (c, d) Depicts two CSPs in which the sac is 6 and 7 mm remote from the bladder

Rac et al. [26] studied 39 patients, of which 14 had histologically confirmed MAP. The smallest myometrial thickness measurement was one of the variables associated with invasion. More research is needed before the gestational-sac-to-bladder distance (see Fig. 17.8) can become useful in counseling patients with CSP in the first trimester of pregnancy.

The Connection Between CSP and MAP

The connection or continuity between CSP and MAP has gradually become evident through clinical observation [27, 28]. We studied placental implantation in the early (second trimester) placenta accreta and in CSP, to find out if they represent different stages in the disease continuum leading to morbidly adherent placenta in the third trimester [29]. Two pathologists, blinded to the diagnosis, evaluated their histologic slides on the basis of these microscopic slides. They could not tell the difference between the two clinical entities and found that both had one thing in common: neither had intervening deciduas between the villi and the myometrium, consistent with the classic definition of morbidly adherent placenta. Therefore, our conclusion is that CSP and an early second trimester placenta accreta are histopathologically identical and represent different stages in the disease continuum leading to MAP in the third trimester.

The next logical question is whether, left untreated, a CSP would result in a live born offspring. We followed ten patients diagnosed with CSPs who opted to continue the pregnancy declining early termination [30]. The diagnosis of CSP was made before 10 weeks. All ten had sonographic signs of MAP by the second trimester. Nine of the ten patients delivered live born neonates, between 32 and 37 weeks. One patient had progressive intractable vaginal bleeding, leading to hysterectomy, at 20 weeks. The other nine patients underwent hysterectomy at the CD. Blood loss ranged from 300 to 6000 mL. Histopathological diagnoses of all placentae was: placenta percreta.

Above, we provided reliable data regarding two clinical issues: (1) CSP is a precursor of MAP, both sharing the same histopathology and (2) pregnancies diagnosed as CSP in the first trimester may proceed to deliver live offspring, risking premature delivery and loss of uterus and fertility. This data can be used to counsel patients with CSP, to make an evidence-based and informed choice between first-trimester termination of an early pregnancy or continuation, risking premature delivery and loss of uterus and fertility.

Map in the First Trimester

MAP can exist in the first trimester of pregnancy. For beginners, Comstock et al. [25] described seven patients after sonographic examination at 10 weeks or earlier with placenta accreta, increta, percreta, not only by their clinical course but, more importantly, by pathologic examination of the uterus. In six, at the time of the early ultrasound, the chorionic sac was located in the lower uterine segment, in the scar area of the previous CD. Two patients underwent D&C, at which time severe bleeding led to hysterectomy. The remaining four had sonographic findings typical of placenta accreta during subsequent scans but delivered at term. The author’s conclusion suggested that, in a patient with a previous CD, a chorionic sac detected by a 10 week or less ultrasound, located in the lower uterine segment, suggests the possibility of placenta accreta. A similar article was published by Ballas et al. [27].

Using our material, Fig. 17.9 depicts the early sonographic markers of a MAP: placenta previa, focal loss of the clear space and focally increased vascularity. The patient in this example delivered at 34 weeks and had placenta accreta. In ten patients, we reported [30] the early sonographic markers of MAP could be detected at the end of the first and beginning of the second trimester.

Fig. 17.9

CSP is a precursor of MAP. This is a 9 weeks and 5 days gestation (Cx cervix, Pl placenta). (a) Sagittal, gray scale image of a CSP with an anterior placenta previa. (b) Power Doppler reveals two areas of vessel proximity to the bladder with loss of the myometrium (arrows). (c) Another plane showing the same findings as in (b). (d) A more lateral section concentrates on an area with clear vessel invasion of the myometrium (arrow)

Counseling Patients with a First-Trimester CSP

Prior to treatment and after the reliable diagnosis of CSP, one has to determine if fetal heart beats are seen. If no yolk sac and/or no embryo and/or no heart beats are seen, re-scan every 2–3 days. If, after a week, no heart activity, no yolk sac and/or no embryo are detected, a sonography and biochemistry based follow-up should be planned. Only after this time should the gestation be considered live or a pregnancy failure and the serum hCG should be followed until nonpregnant levels are reached. Some management protocols call for systemic administration of MTX, even with the absence of heart beats for early drug effect. While such an approach is not contraindicated, the patient and the provider must be sure that under no circumstances is this a wanted pregnancy.

In the case of positive heart activity, counseling should enumerate the two main, clinical management options to reach a decision as early as possible. The two options before further growth of the gestation are: (1) termination or (2) continuation of the pregnancy. Our counseling of patients with a CSP diagnosed in the first trimester of pregnancy underwent a fundamental change. Several years ago we would counsel toward termination of the pregnancy without delay. Recent studies on the natural history of the CSP, with the possibility of reaching term or near term delivery of a live offspring, has changed our counseling. We provide the patient with evidence that this is possible and that the patient should understand that a placenta accreta at the CD may necessitate hysterectomy. Management in the above case should be based on the patient’s age, number of previous CDs, desired number of children, and the expertise of the clinicians giving the care. If the patient decides to continue the pregnancy, bleeding precautions should be given. The management should be based upon serial ultrasounds, until a safe gestational age is reached. A multidisciplinary team should be involved in the delivery and blood products should be available, since ultrasound cannot predict the blood loss at surgery. Our general guidelines in counseling and managing the patient with a CSP are shown in Fig. 17.10.

Fig. 17.10

Triage and management of CSP by the presence or absence of cardiac activity

Management of CSP

Treatment regimens and their combinations can be classified as one of the following:

1.

Major Surgery (these require general anesthesia)

(a)

Laparotomy (hysterectomy or local excision)

(b)

Excision by laparoscopy, hysteroscopy or by transvaginal surgery

(c)

Dilatation of the cervix and sharp or blunt curetting

(d)

Suction aspiration without dilatation of the cervix

(e)

Excision performed by the vaginal route

The last two can be guided by continuous, real-time ultrasound.

2.

Minimally invasive surgery (does not involve general anesthesia)

(a)

Local injection of MTX or KCl

(b)

Vasopressin locally was also used

3.

Systemic medication

(a)

Single or repeated doses of MTX and etoposide (some articles originating from China advocate intravenous use of MTX claiming reasonable success)

(b)

Uterine artery embolization (UAE)

4.

Combination of the above treatments. A large number of articles report on combining treatments in a planned, simultaneous or sequential fashion. Treatments are also changed, mostly after the first-line therapy failed. As a matter of fact, it is rare to find a recently (2012–2014) published case or case series in which the patients were managed only by one single treatment agent or protocol.

5.

Adjuvant measures. Most recently, Foley balloon placement and inflation to prevent and/or control bleeding, following local treatments such as aspiration, curettage and local injection.

It is beneficial for the patient with CSP to be referred to a facility that provides evidence-based care as well as experienced in managing cases, in response to developing emergency situations. Such centers should be able to provide operating rooms, interventional radiology procedures and have available immediately blood transfusion/blood products. The latter, since bleeding complications is typical of this dangerous clinical entity.

Treatment Options Available for CSP

Based upon the in-depth and available literature, analyzing the different aspects of CSP, in 2012 there were about 33 published treatment modalities with their results and complications [4]. No preferred treatment became apparent, however, of the 751 patients D&C (305), surgical excision (laparoscopic, hysteroscopic and transvaginal) (261), UAE (142), MTX (92), and local, intragestational sac injection (86) were the most used.

Between 2012 and 2014, no less than 1223 cases of CSP were published in about 61 peer-reviewed articles. Not surprising is the fact that Chinese authors contributed 91 % of the cases, describing their various and different treatment modalities/combinations of managing approximately 1115 patients. This is due to their large population and over 40 % CD rate. At least 36 primary or combination treatments were found; however, the number is not substantially different from the list of treatment approaches described in our review of 751 cases. No wonder one cannot draw a clear conclusion as to which treatment was the most effective, resulting in the least or no complications. This large number underlines the fact that, in 2015, there is no nationally/internationally agreed upon or suggested management protocol published with a set of guidelines to manage CSP or early first-trimester placenta accreta. While the distribution of the various treatments and their rates of use are found in the tables of our previous review [4], the somewhat different distribution of treatment choices are detailed in Table 17.1.

Table 17.1

Treatment options for CSP

Treatments: single or in combination | No. of patients | Percent of 1223 patients (%) |

|---|---|---|

Dilatation and curettage | 577 | 52.4 |

Uterine artery embolization | 309 | 28.0 |

Methotrexate | 236 | 21.4 |

Suction aspiration | 81 | 12.0 |

Transvaginal excision | 119 | 9.7 |

Laparoscopic excision | 94 | 7.7 |

Hysteroscopic excision or guidance | 63 | 5.2 |

Excision by laparotomy or straight TAH | 15 | 1.2 |

High-frequency ultrasound | 20 | 1.6 |

Despite several treatments for CSP our detailed discussion will be limited to the most used. A much more detailed analysis is found in our in-depth review [4], complete with their efficacy and complication rates. We now add the pertinent data resulting from the review of the 1223 cases published after 2012.

Suction Aspiration or D&C, Alone or in Combination

Based on our first review of treating 305 cases with D&C only or in combination with other means as a “first line” or a backup, therapy had a mean complication rate of about 62 % (range, 29–86 %) [4]. The main complication was unanticipated bleeding, forcing an emergency second or third-line treatment that, almost always, was surgical. At times, hysterectomy became necessary. This option requires general anesthesia.

There were some changes between the results of the two reviews. If D&C was used as a sole treatment, in 69 cases 24 (34.7 %) resulted in complication as opposed to first line or secondary treatment combined with other treatments. Only 52 of 413 (12.2 %) had complications. If UAE was combined with systemic MTX it caused 35 % complications, while combined with other means (e.g., suction evacuation or hysteroscopic excision among others), the rate was only 11.3 %.

As opposed to a spontaneous delivery or spontaneous abortion, where the uterine myometrial grid constricts the bleeding after placental separation, in CSP, the sharp curettage exposes vessels of the gestational sac leading to severe and sometimes unstoppable bleeding since there is less or no adequate muscle grid to contain the bleeding. A sharp curettage might injure the thin myometrium leading to bleeding or even perforation.

If D&C or suction aspiration is still the preferred treatment, blood and blood products as well as a Foley balloon catheter should be readily available [31]. Foley balloon catheters were successfully used to stop and tamponade possible bleeding [32, 33]. Cali et al. [34] successfully used the following sequential treatment approach in eight of their patients. At admission to the hospital, the patient undergoes UAE and, after 5 days, a gentle suction aspiration under continuous, real-time ultrasound is performed by immediate insertion and inflation of a Foley balloon catheter for bleeding prevention and control [31].

A number of recent articles advocate the safe and uncomplicated use of blunt sac aspiration; however, all were followed or preceded by other treatment methods [35]. Interestingly, no complications were seen in 81 suction aspirations in our review of the cases between 2012 and 2014. This probably is attributed to its blunt, as opposed to a sharp curetting at the time of D&C, therefore, less prone to disrupt blood vessels.

Uterine Artery Embolization, Alone or in Combination

This treatment requires general anesthesia. If used as a primary and only treatment, the complication rate among the 64 cases described in the review of 751 cases of CSP was 47 %. It is difficult to evaluate the real complication rates, due to partial or incomplete data in the published articles. In another 78 cases, UAE was used in combination with other treatments. It seems that UAE is not the best first-line treatment, if administered alone as a single agent therapy, since it allows the pregnancy, with its vascularity, to grow and increase. For this reason, Cali et al. [34] delayed suction aspiration in their patients with CSP for 5 days after UAE. Uterine artery embolization works better combined with other noninvasive and invasive (suction aspiration) treatments [36–38]. In our 60 cases of CSP, UAE was used as a secondary treatment in four patients with persistent vaginal bleeding or developing AVM. Embolization failed to stop the bleeding in one of the patients with AVM, therefore, hysterectomy was performed [24].

If UAE fails, which may be the case, the clinician must contend with a larger gestation applying a secondary treatment. However, it is hard to evaluate its actual complication rates, since some articles have insufficient data to rely on. As stated previously, in our 60 cases of CSP, one of the patients required (and finally agreed to) AVM embolization to stop her continuing vaginal bleeding (as well as her high PSV on Doppler), 122 days after her initial local MTX injection (Fig. 17.11).