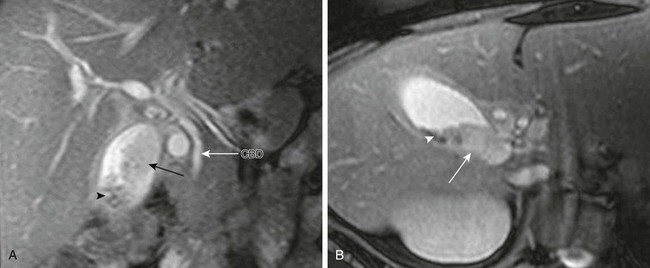

Chapter 89 Overview: Although in the past cholelithiasis was believed to be rare in children without hemolytic anemia, it is being diagnosed more frequently as a result of increased utilization of sonography. In fact, the sonographic finding of gallstones has been reported in fetuses, although most of these gallstones resolve spontaneously.1 Etiology: Development of gallstones in infants may be related to immature physiologic regulation of bile salt secretion. Chronic cholestasis likely plays a role in the pathophysiology of cholelithiasis. Although gallstones in infants often are discovered incidentally, many predisposing conditions have been described (Box 89-1). Gallstones in infants resolve spontaneously less often than in fetuses. Further, stones in infants are rarely complicated by biliary tract perforation and peritonitis.2 Although most of the stones seen in older children are idiopathic, a number of underlying states have been associated with gallstones (Box 89-2). Prominent among these states are sickle cell disease and intestinal problems that interfere with normal enterohepatic circulation.3 Patients with sickle cell disease and other hemolytic anemias have an increased incidence of gallstones with advancing age. Gallstones also have been reported after surgery and antibiotic therapy.4 Clinical Presentation: Cholelithiasis usually is asymptomatic in infants and young children, with an increased incidence of symptoms in older children. When symptoms occur in older children and adolescents, they are similar to those seen in adults and include bloating, nausea, vomiting, and postprandial right upper quadrant colicky pain radiating to the shoulder. In younger children the presentation may be nonspecific (such as irritability), because young children may not be able to verbalize or relate their discomfort to the right upper quadrant or to a recent meal.5 Choledocholithiasis results from migration of stones from the gallbladder into the common duct. Stones are more likely to be symptomatic when they pass into the cystic duct or the common bile duct. The most common complication of gallstones in children is pancreatitis,5 although the most common cause of pancreatitis is idiopathic or posttraumatic.6 Imaging: Although radiolucent cholesterol stones are the most common type overall, they are rare in children, and thus the majority of pediatric gallstones are visible radiographically. Even so, sonography remains the primary imaging modality for the evaluation of cholelithiasis (Fig. 89-1). Three main sonographic criteria are used to diagnose gallstones: (1) echogenic focus, (2) acoustic shadowing, and (3) gravitational dependence. Most stones move with change in patient position, which should be a routine maneuver during hepatobiliary sonography (Fig. 89-2). Four general sonographic patterns of cholelithiasis are described. The first pattern includes the simple echogenic, shadowing, mobile stone, which may be single or multiple. The second pattern of cholelithiasis describes collections of very tiny, sandlike stones, termed milk of calcium, which may mimic gallbladder sludge; acoustic shadowing may be seen only in the aggregate (see Fig. 89-2).7 Occasionally, if bile within the gallbladder is of high density, the stones may seem to float on the surface, giving an apparent fluid-fluid level. The last sonographic pattern of cholelithiasis relates to stones within a contracted gallbladder, in which case the stones produce an echogenic double arc known as the wall echo shadow (WES) complex. This pattern may be seen in patients with a chronically contracted gallbladder or those who have not fasted sufficiently (Fig. 89-3). Careful scrutiny must be used so as not to confuse the WES complex with emphysematous cholecystitis (air in the gallbladder wall), which is far more common in adults than in children.8 Figure 89-1 Cholelithiasis in a 17-year-old girl with abdominal pain. Figure 89-2 Cholelithiasis in a 16-year-old girl with right upper quadrant pain. Figure 89-3 Cholelithiasis in a 16-year-old girl with abdominal pain. Sonography is less successful at revealing choledocholithiasis than it is at detecting cholelithiasis because of interference from gas in adjacent bowel. Therefore dilated extrahepatic bile ducts (Fig. 89-4) may be the only sonographic sign of a more distal obstructing stone. Computed tomography (CT) scans9 might be obtained in children with biliary stones if other abdominal processes initially are clinically suspected. CT is inferior to sonography with regard to revealing the actual stone, but it readily demonstrates biliary dilation.6 If no stone is seen on sonography yet evidence exists of biliary ductal dilation, magnetic resonance cholangiopancreatography (MRCP) may be helpful. With MRCP, stones are seen as low signal intensity filling defects within the gallbladder and the biliary tree (Figs. 89-5 and 89-6).10 Figure 89-4 Choledocholithiasis in a 15-year-old girl with sickle cell disease and abdominal pain. Figure 89-5 Choledocholithiasis in a 17-year-old boy with Duchenne muscular dystrophy and jaundice. Figure 89-6 Cholelithiasis in a 12-year-old girl with abdominal pain.

Acquired Biliary Tract Disease

Cholelithiasis and Choledocholithiasis

A transverse sonogram of the gallbladder shows cholelithiasis (arrow) with associated posterior acoustic shadowing (S).

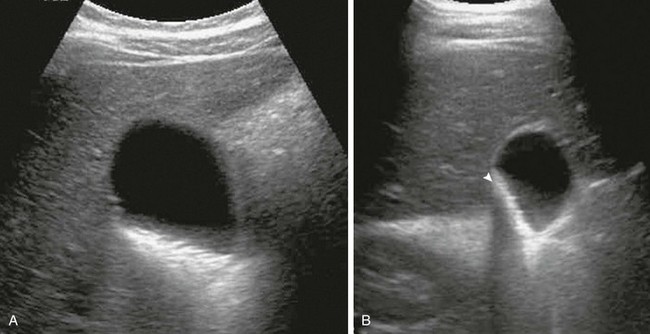

Transverse sonograms in the supine (A) and decubitus (B) positions reveal echogenic layering of tiny stones. Note the change in stones with change in patient position, as well as diffuse shadowing of the stone aggregate (arrowhead in B).

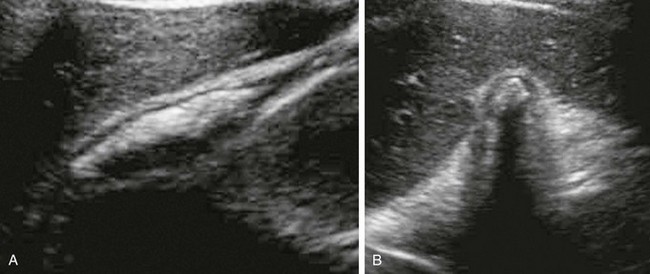

Longitudinal (A) and transverse (B) sonograms performed without fasting show the anterior gallbladder wall and multiple echogenic stones with posterior acoustic shadowing (wall-echo-shadow triad).

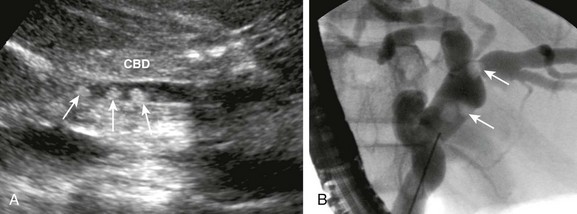

A, Sonogram of the common bile duct (CBD) reveals three stones (arrows). B, Subsequent endoscopic retrograde cholangiopancreatography shows dilated bile ducts and intraluminal filling defects (arrows).

Three-dimensional reformatted T2-weighted sequences from a magnetic resonance cholangiopancreatogram show a filling defect consistent with a stone (arrow) in the distal common bile duct. A small stone was removed at subsequent endoscopic retrograde cholangiopancreatography.

Coronal (A) and axial T2-weighted (B) magnetic resonance images reveal low signal intensity gallstones (arrowheads) and isointense sludge (arrows) within the gallbladder lumen. Note the normal common bile duct (CBD) (long white arrow in A).

Biliary Sludge