Fig. 1

Pancreas anatomy (Image courtesy of Corrine Winston, MD)

The majority of pancreatic adenocarcinomas arise in the head of the pancreas, which lies anterior and to the right side of the vertebral column and adjacent to the first part of the duodenum. Tumors arising here tend to be identified earlier than those in the body or tail because they obstruct the distal common bile duct and often present with painless jaundice (most common), a dilated gallbladder (Courvoisier’s sign), or less commonly with cholangitis (Niederhuber et al. 2014).

The boundary between the head and neck of the pancreas is marked anteriorly by a groove for the gastroduodenal artery and posteriorly by a deep groove from the union of the superior mesenteric and splenic veins, which form the portal vein (Strandring 2005).

The body of the pancreas is the largest part of the gland and is located to the left of the superior mesenteric vein (SMV), extending to the left border of the aorta. The pancreatic tail extends from the left border of the aorta to the splenic hilum and lies between the layers of the splenorenal ligaments. The splenic vein forms a shallow groove on the posterior border of the gland (Strandring 2005).

The accessory lobe of the pancreas, or uncinate process, extends from the inferior lateral end of the head of the gland. It is an anatomically and embryonically distinct portion of the gland, and as a result it lies posterior to the superior mesenteric vessels. Inflammation of the pancreas can result in compression of the superior mesenteric artery (SMA) and SMV between the uncinate process and the neck of the pancreas. Tumors of the uncinate process may not cause obstruction of the common bile duct, but rather can compress the third portion of the duodenum or, rarely, result in thrombosis of the SMA or SMV.

Given the exocrine function of the pancreas, some tumors can present with signs/symptoms of enzyme insufficiency (i.e., malabsorption, increased flatulence, fatty stools, weight loss, and ascities). Diabetes can also be a presenting symptom given the endocrine function of the gland.

The main pancreatic duct, the duct of Wirsung, lies within the substance of the gland with increasing caliber as it approaches the ampulla in the descending duodenum (papilla of Vater). A separate accessory duct, the duct of Santorini, drains the lower part of the head and uncinate process and usually enters the duodenum at a minor papilla approximately 2 cm proximal to the major papilla of Vater. The main and accessory ducts have anatomic variability, but in many adults the main pancreatic duct merges with the common bile duct proximal to the papilla of Vater (Strandring 2005).

Sympathetic innervation of the pancreas originates from the 6th to the 10th thoracic spinal segments. Parasympathetic innervation is from the posterior vagus nerve and the parasympathetic celiac plexus. Referred pain from the pancreas is poorly localizing, but often described as a dull deep abdominal or middle back pain (Niederhuber et al. 2014).

Pain at time of diagnosis has been correlated with a worse prognosis as it is usually indicative of locally advanced disease or perineural invasion.

The pancreas has a rich arterial supply. The head and neck of the pancreas are supplied from the superior and inferior pancreaticoduodenal arteries. which arise from the celiac trunk and SMA, respectively. Venous drainage is predominantly through the splenic vein. Given their intimate proximity to the pancreas, the SMA and SMV are most commonly involved. Vascular invasion is a critical factor to consider when assessing the surgical resectability of the tumor (Niederhuber et al. 2014).

Lymph node involvement is the strongest predictor for survival. The first echelon nodes include the pancreaticoduodenal, suprapancreatic, pyloric, and splenic hilar (if lateralized body or tail tumor) lymph nodes. Second echelon nodes include the celiac nodes, porta hepatis, and superior mesenteric and para-aortic nodes.

The majority of patients (>85 %) present with locally advanced or metastatic disease. Given the location of the gland in the retroperitoneum, the most common sites of local invasion include the duodenum, SMV, portal vein, SMA, stomach, liver, and gallbladder.

The liver is the most common site of metastasis as venous drainage of the pancreas is predominantly through the portal system. Peritoneal metastases are also common. The lung is the most common site of metastatic disease outside the abdomen. Brain and bone metastases are uncommon.

Local control in pancreatic adenocarcinoma is important, as approximately 30 % of patients die from the significant morbidity associated with locally advanced disease (Iacobuzio-Donahue et al. 2009).

2 Diagnostic Workup Relevant for Target Volume Delineation

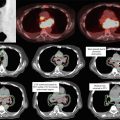

In addition to physical examination, adequate imaging studies should be obtained for diagnosis, staging, and planning. Unless contraindicated (renal disease/allergy), all patients should undergo a computed tomography (CT)-angiogram pancreas protocol. Alternatively, MRI may be considered if an iodinated contrast allergy is present. Positron-emission tomography (PET)/CT may be considered, but its contribution to target delineation has not been fully characterized.

CT-angiogram pancreas protocol often includes a non-contrast phase plus arterial, pancreatic parenchymal, and portal-venous phases of contrast enhancement with thin cuts (3 mm or less) through the abdomen. Multiplanar reconstruction is preferred (Network NCC 2013).

This technique allows precise visualization of the relationship of the primary tumor to the mesenteric vasculature as well as detection of metastatic deposits as small as 3–5 mm (Network NCC 2013).

In patients with localized disease, an endoscopic ultrasonography (EUS) should be considered to help evaluate resectability and obtain tissue to confirm diagnosis.

EUS-directed fine-needle aspiration (FNA) is preferable to a CT-guided FNA because of improved diagnostic yield, safety, and a potentially lower risk of peritoneal seeding compared with percutaneous approaches (Network NCC 2013).

Borderline resectable and unresectable patients with obstructive jaundice should undergo biliary stenting prior to initiating radiation therapy planning, preferably with a metal wall stent.

Laboratory workup should include complete blood count, carcinoembryonic antigen, CA19-9, glucose, amylase, lipase, bilirubin, alkaline phosphatase, lactate dehydrogenase, and liver function tests.

Pretreatment CA19-9 <90 U/mL has been correlated with improved overall survival (Berger et al. 2008).

3 Pancreatic Cancer Staging

An American Joint Committee on Cancer (AJCC) TNM staging exists for pancreatic exocrine cancer; however, the most commonly used classification is based on resectability and evidence of metastatic disease (Edge et al. 2010). Pancreatic tumors are largely categorized into three groups: (1) resectable; (2) locally advanced, nonmetastatic; and (3) metastatic. More recently, tumors that are considered “borderline resectable” have been defined by several groups; however, this remains a less well-characterized subset.

Criteria for resectability vary by institution and surgical technique/experience:

Tumors considered localized and clearly resectable should demonstrate the following: (1) no distant metastases, (2) no radiographic evidence of SMV or portal vein distortion, and (3) clear fat plane around the celiac axis, hepatic axis, and SMA. Splenic vein involvement is permissible (Network NCC 2013; Callery et al. 2009).

Tumors considered to be borderline resectable have the following: (1) no distant metastases; (2) venous involvement of the SMV or portal vein with distortion or narrowing of the vein or occlusion of the vein with suitable vessel proximal and distal, allowing for safe resection and replacement; (3) gastroduodenal artery encasement up to the hepatic artery with either short-segment encasement or direct abutment of the hepatic artery, without extension to the celiac axis; and (4) tumor abutment of the celiac axis or SMA not to exceed greater than 180° of circumference of the vessel wall (Network NCC 2013; Callery et al. 2009).

Unresectable disease is usually characterized by one or more of the following features: (1) distant metastasis or extensive peripancreatic lymph node involvement, (2) encasement or occlusion of the SMV or SMV/portal confluence, and (3) direct involvement of the SMA, inferior vena cava, aorta, or celiac axis (Network NCC 2013; Callery et al. 2009).

4 Locally Advanced, Unresectable Pancreatic Adenocarcinoma

4.1 General Points

While radiation therapy remains controversial, it is often considered the only definitive option for patients with locally advanced unresectable pancreatic adenocarcinoma.

The principles of radiotherapy in patients undergoing neoadjuvant and definitive radiation are similar.

Intensity-modulated radiation therapy (IMRT) is becoming the standard technique for definitive or neoadjuvant radiation therapy for locally advanced and borderline resectable pancreatic adenocarcinoma and is preferred over three-dimensional chemoradiation therapy (3D-CRT), given that it is associated with less treatment-related toxicity (decreased nausea, vomiting, and diarrhea) (Yovino et al. 2011).

Depending on patient anatomy and tumor location, treatment recommendations can include conventionally fractionated IMRT or stereotactic body radiation therapy (SBRT).

Ideal candidates for SBRT are those with tumors <5 cm without abutment of adjacent critical organs such as the stomach, liver, non-duodenal small bowel, and large bowel.

5 Conventionally Fractionated Chemoradiation Therapy for Unresectable Pancreatic Adenocarcinoma

5.1 Simulation and Daily Localization

Motion management should be considered for patients being treated with definitive chemoradiation for locally advanced unresectable pancreatic adenocarcinoma given the significant tumor and normal tissue motion with respiration.

Motion management may be addressed by several techniques, including respiratory gating, breath hold (active breathing control [ABC]), respiratory tracking, or abdominal compression.

For patients treated with motion-management techniques, fiducial markers should be placed prior to simulation (preferably at least 5 days prior to simulation due to the possibility of migration) to assist in motion management using percutaneous, intraoperative, or endoscopic techniques.

CT simulation with oral and IV contrast (unless contraindicated) should be performed to help guide the gross tumor volume (GTV) target as well as lymph node coverage.

Patients are generally asked not to eat any large meals 2–3 h prior to simulation and treatment to avoid significant interfraction variation in stomach distention.

Arms should be above the head in the alpha cradle, with oral and IV contrast.

Planning scan should be obtained using pancreatic protocol (minimum of 3 mm cuts) with a scan from carina to iliac crest.

If using respiratory gating or breath-hold technique for motion management, the planning scan should be performed during a breath hold at end expiration using voice coaching.

For patients treated with respiratory gating or without a specific motion-management technique, a four-dimensional (4D) CT is necessary to evaluate the degree of tumor motion. The motion can be accounted for with an internal target volume or can guide the gating interval for patients undergoing respiratory gating.

Typical anatomic landmarks that can help in guiding clinical target volume (CTV) delineation include:

Pancreas generally lying at L1–L2

Celiac axis generally lying at T12

SMA generally lying at L1

5.2 Target Volume Delineation and Treatment Planning

The GTV is contoured on the treatment-planning expiratory phase CT after reviewing the diagnostic CT, respiratory-correlated 4D-CT, pancreas protocol CT, PET-CT, and/or MR abdomen if applicable.

The CTV includes a 1 cm expansion off the GTV and should encompass all relevant nodal regions (Table 1).

Table 1

Target volumes

Target volumes

Definition and description

GTV

Consists of the hypodense area in the pancreas, if visible, corresponding to biopsy-proven disease, and any positive lymph nodes visualized on diagnostic pancreatic protocol CT, parenchyma, or portal-venous phase. The tumor may be isointense with the normal pancreas, and it may be difficult to distinguish the tumor boundaries. In addition, pancreatic tumors tend to be highly infiltrative, and extrapancreatic spread may appear as soft tissue encasement of the adjacent vessels or even just soft tissue stranding in the abdominal fat. Consultation with a diagnostic radiologist may aid in determining the extent of the GTV (GTV should be contoured on the IV-contrast planning scan in the end-expiration phase)

CTV

The CTV encompasses all relevant nodal regions including the porta hepatis, celiac/SMA, and PA/RP lymph nodes approximately from the top of T11 to bottom of L2, but may often be smaller than this and should be adjusted based on location of primary tumor; the superior–inferior extent is primarily determined by overlapping coverage of the appropriate nodal regions and tumor location. The CTV should also include areas of subclinical direct tumor extension. In general, the GTV is also expanded by 1 cm; this expansion is then added to the nodal CTV

PTV

Expansion on the CTV by 5 mm (receives 5,040 cGy in 180 cGy fractions)

PTV boost

Expansion on the GTV by 3–5 mm margin, shrinking the margin to <3 mm to minimize overlap with the duodenum. Note that this is an integrated boost guideline based on Memorial Sloan Kettering Cancer Center standard practice, and the PTV boost receives 5,600 cGy in 200 cGy fractions

Get Clinical Tree app for offline access

Lymph node coverage

Head/neck/proximal body lesions

Pancreaticoduodenal, suprapancreatic, porta hepatis, celiac, superior mesenteric, and para-aortic lymph nodes at the level of the tumor and/or celiac axis/SMA

Distal body/tail lesions

Pancreaticoduodenal, suprapancreatic, splenic hilar, celiac, superior mesenteric, and para-aortic lymph nodes at the level of the tumor and celiac axis/SMA

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree