Bone-forming neoplasms are characterized by the formation of osteoid or mature bone directly by the tumor cells. They include osteoma, osteoid osteoma, and osteoblastoma.

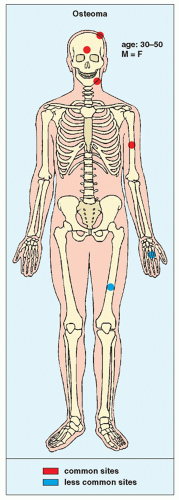

Osteoma

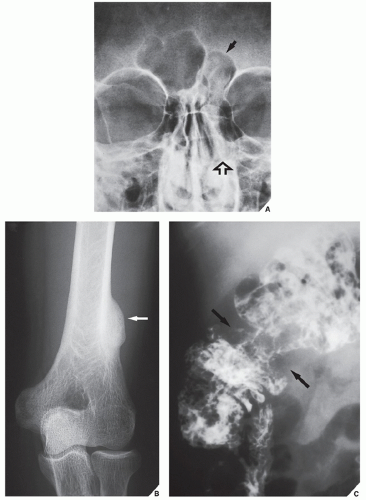

An osteoma is a slow-growing osteoblastic lesion commonly seen in the outer table of the calvarium and in the frontal and ethmoid sinuses. It is also occasionally encountered in long and short tubular bones, and at these sites, it is known as a

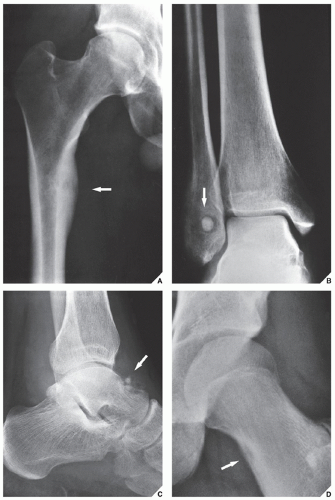

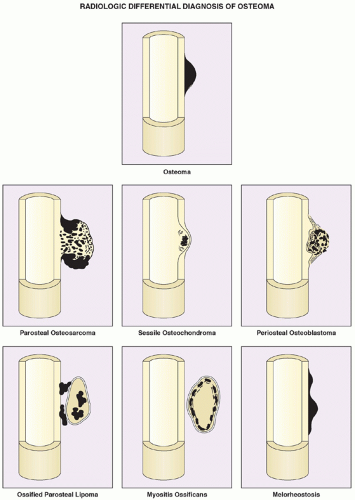

parosteal osteoma. The lesion grows on the bone surface and has the radiographic appearance of a dense, ivory-like sclerotic mass attached to the cortex with sharply demarcated borders (

Fig. 17.1). Osteomas have been reported in patients from ages 10 to 79 years, with most in the fourth and fifth decades. Men and women are equally affected (

Fig. 17.2). Histologically, osteoma is composed primarily of bone, with a mature lamellar architecture consisting of concentric rings as in compact bone or, more commonly, parallel plates as in cancellous bone. An osteoma is an asymptomatic lesion that does not recur if excised surgically. Its importance lies in its similar radiographic presentation to the more aggressive parosteal osteosarcoma (see

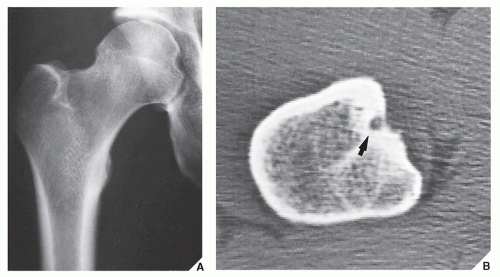

Fig. 16.35) and its common association with cutaneous and subcutaneous masses and intestinal polyps in the condition known as

Gardner syndrome (

Fig. 17.3). Intestinal adenomatous polyps, particularly in the colon, may undergo a malignant transformation to carcinoma. The syndrome is a familial, autosomal dominant disorder, frequently seen in Mormons in Utah. The cause of this syndrome is linked to mutation in the

APC gene located in chromosome 5q21.

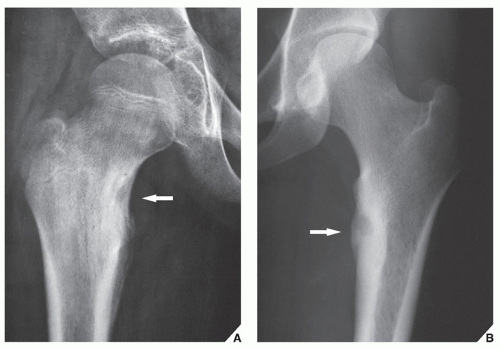

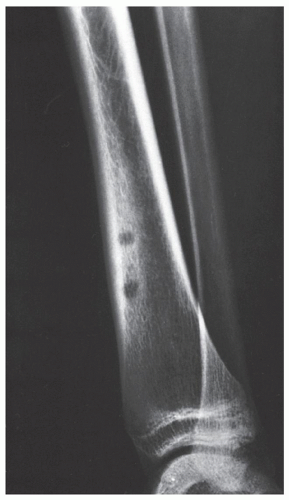

Osteoid Osteoma

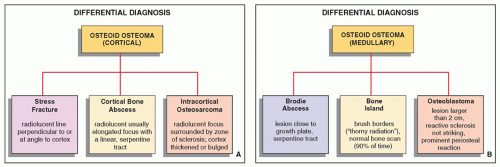

Osteoid osteoma is a benign osteoblastic lesion characterized by a nidus of osteoid tissue, which may be purely radiolucent or have a sclerotic center. The nidus has limited growth potential and usually measures less than 1 cm in diameter. It is often surrounded by a zone of reactive bone formation (

Fig. 17.5). Very rarely, an osteoid osteoma may have more than one nidus, in which case it is called a

multicentric or

multifocal osteoid osteoma (

Fig. 17.6). Depending on its location in the particular part of the bone, the lesion can be classified as cortical, medullary (cancellous), or subperiosteal. Osteoid osteomas can be further subclassified as extracapsular or intracapsular (intraarticular) (

Fig. 17.7). These lesions occur in the young,

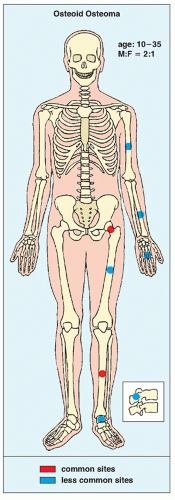

usually between the ages of 10 and 35 years, and their sites of predilection are the long bones, particularly the femur and tibia (

Fig. 17.8). Cytogenetic analysis performed in a few cases of this lesion reveled chromosomal alterations involving chromosome 22 [del(22)(q13.1)].

The most important clinical symptom of osteoid osteoma is pain that is more severe at night and is dramatically relieved by salicylates (aspirin) within approximately 20 to 25 minutes. This typical history holds in more than 75% of cases and serves as an important clue to the diagnosis.

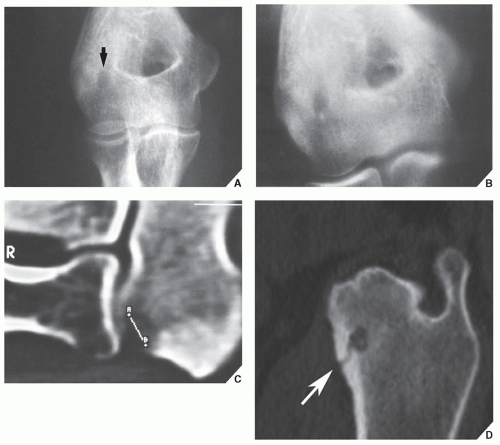

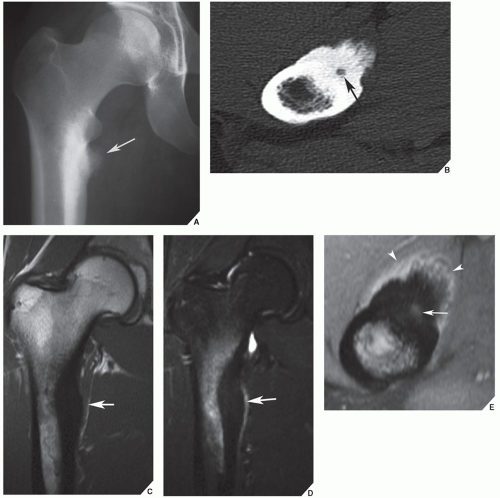

Standard radiographs may demonstrate the lesion, but CT (

Fig. 17.9) is required to demonstrate the nidus and localize it precisely. CT has the added advantage of allowing exact measurement of the size of the nidus (

Fig. 17.10A-C). Furthermore, a recent study indicated the high specificity of a new CT sign of osteoid osteoma, the so-called

vascular groove sign. This sign reflects the vascular channels created by arterioles supplying the nidus of an osteoid osteoma (

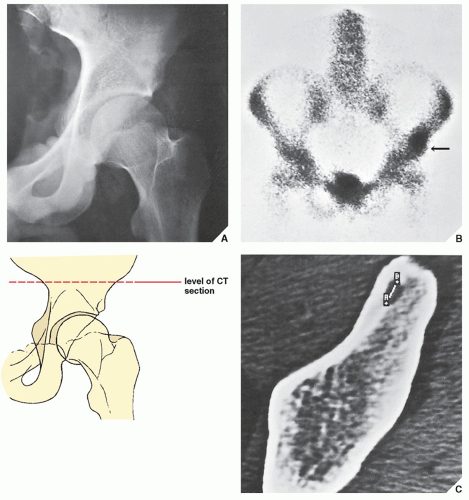

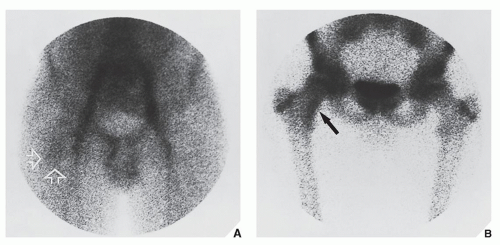

Fig. 17.10D). Frequently, when the lesion cannot be demonstrated radiographically, a radionuclide bone scan is helpful because osteoid osteoma invariably shows a marked increase in isotope uptake (

Fig. 17.11). This modality can be particularly helpful in cases for which the symptoms are atypical and the initial radiographs appear normal. The use of a three-phase technique is recommended. Radionuclide tracer activity can be observed on both immediate and delayed images (

Fig. 17.12). If the nidus is demonstrated radiographically, the diagnosis can usually be made with great assurance; only atypical presentations create diagnostic difficulty (

Fig. 17.13).

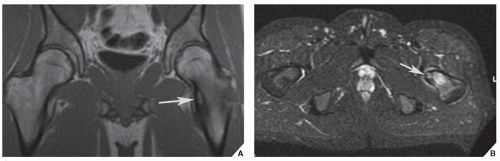

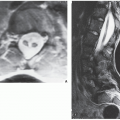

The suitability of magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) for the detection of osteoid osteoma remains unclear, and published reports have shown mixed results. Goldman and associates reported on four cases of intracapsular osteoid osteoma of the femoral neck, in which the lesions were evaluated with bone scintigraphy, CT, and MRI. Although in all cases abnormal findings were apparent in the MR images, the nidi could not be identified prospectively. On the basis of MRI findings of secondary bone marrow edema or synovitis, several incorrect diagnoses were made, which included Ewing sarcoma, osteonecrosis, stress fracture, and juvenile arthritis. In these cases, it is noteworthy that the correct diagnoses were made only after review of the radiographs and thin-section CT studies. Another report by Woods and associates involved three patients with a highly unusual association of osteoid osteoma with a reactive soft-tissue mass. In these cases, MRI studies might have led to confusion of osteoid osteoma with osteomyelitis or a malignant tumor. Moreover, in each case, the nidus displayed different signal characteristics. In one case, the intensity of signal was generally low on all pulse sequences, but mild enhancement was seen after administration of gadolinium. In another case, the signal was of intermediate intensity, and administration of gadolinium revealed in homogeneous enhancement of the nidus. For the third case, in which radiographs showed the nidus to be intracortical, MRI could not identify the nidus distinctly.

However, some reports do suggest the effectiveness of MRI for demonstrating the nidus of osteoid osteoma (

Figs. 17.14 and

17.15). Bell and colleagues clearly demonstrated an intracortical nidus on MRI that had not been seen on scintigraphy, angiography, or CT scans. In particular, imaging of osteoid osteoma with dynamic gadolinium-enhanced MR technique demonstrated greater conspicuity in detecting the lesion than with nonenhanced MRI.

Recently, Ebrahim and associates reported sonographic findings in patients with intraarticular osteoid osteoma. Ultrasound images revealed focal cortical irregularity and adjacent focal hypoechoic synovitis at the site of intraarticular lesions. The nidus was hypoechoic with posterior acoustic enhancement, and color Doppler imaging identified a vessel entering a focus of osteoid osteoma. It is noteworthy, however, that the authors concluded that the accuracy of sonography in the diagnosis of intraarticular osteoid osteoma cannot be certain because other intraarticular pathologic conditions, for example, inflammatory synovitis, may have a similar appearance. Therefore, one should seek corroborative features of this lesion using other imaging techniques, such as CT or MRI.

Histologically, the nidus is composed of osteoid or even mineralized immature bone. It is a small, well-circumscribed, and self-limited lesion. Its microtrabeculae and irregular islets of osteoid matrix and bone are surrounded by a richly vascular fibrous stroma in which osteoblastic and osteoclastic activities are often prominent. The perilesional sclerosis is composed of dense bone displaying a variety of maturation patterns.

Get Clinical Tree app for offline access

Get Clinical Tree app for offline access