JEONG MI PARK, WILLIAM E. ERKONEN, AND LAURIE L. FAJARDO

What We Should See on a Mammogram

Indications for Breast Ultrasound

Suggested Workup of Common Clinical Problems

This chapter is short, but its importance is unrelated to its length. There are a number of good textbooks on this subject that are more encyclopedic, and you can and should refer to these (1–3). The purpose of this chapter is to stress the importance of mammography, ultrasound (US), and magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) in the management of breast disease and the screening for early cancer detection.

Approximately one in eight females in the United States will develop cancer of the breast during her lifetime, and this incidence appears to be increasing. Breast cancer currently involves over 180,000 women per year in the United States, and it causes approximately 40,000 deaths per year. An effective strategy to decrease the mortality associated with this disease is to find the lesions at an early and curable stage. Mammography can detect early invasive lesions or carcinomas in situ that measure only a few millimeters before they become symptomatic and/or palpable. It is generally believed that the earlier breast cancer is diagnosed, the smaller the chance of metastases. Consequently, mammography is widely used as a routine screening tool to detect occult breast cancer in the general asymptomatic female population. However, screening mammography must always be used in conjunction with monthly breast self-examination and an annual breast examination performed by a physician. A National Cancer Institute review showed that this approach significantly reduces breast cancer deaths for women of all ages.

Mammography is also a key tool in the evaluation of known or suspected breast disease in both males and females. A variety of special diagnostic mammographic studies such as spot compression or magnification mammography are used to supplement a routine screening examination when symptomatic patients are examined.

There is little doubt that mammograms must be interpreted by qualified radiologists, and the radiologist’s role in breast disease continues to increase. Radiologists are more frequently being called on to perform breast procedures such as percutaneous breast biopsies. Given the prevalence of breast problems, all physicians should be aware of the basics of breast imaging, including the limitations of mammography.

Diagnostic mammography should be performed whenever the patient has any symptom, the physician finds a problem, or a radiologist finds some abnormality on a screening mammogram. Screening mammography can be performed for normal, nonsymptomatic patients under recommended guidelines. Some generally accepted guidelines for screening mammography are listed in Table 10.1. These guidelines provide you with something on which you can hang your hat, but there isn’t unanimous agreement about them. As indicated in the guidelines in Table 10.1, risk factors are important and influence the timing for mammography. Some of the common risk factors are listed in Table 10.2. Depending on the risk factors, the time tables may be advanced to younger ages.

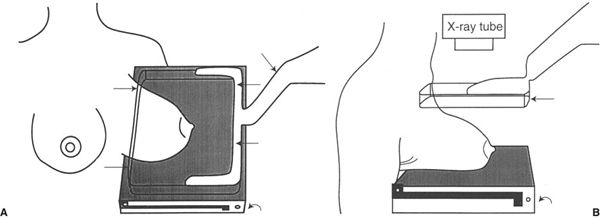

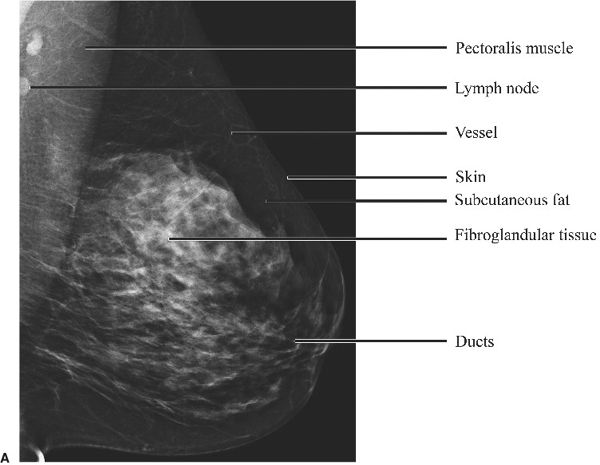

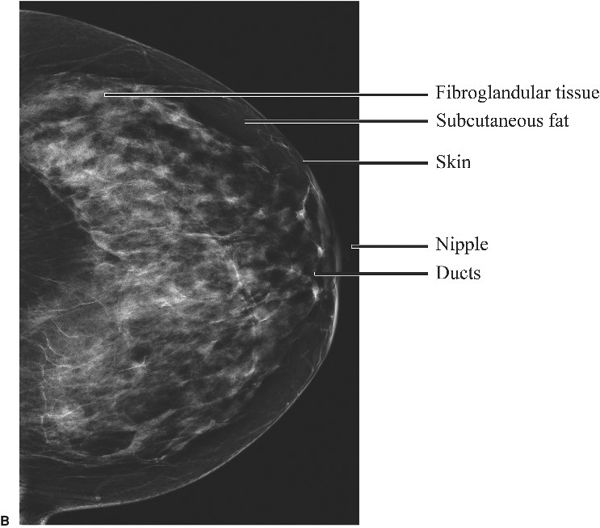

The importance of a well-performed mammogram cannot be overemphasized. A standard screening mammogram consists of a mediolateral oblique (MLO) view with the central x-ray beam traversing the breast obliquely in a medial to lateral direction (Fig. 10.1A) and a craniocaudal (CC) view (Fig. 10.1B) with the central x-ray beam traversing the breast in a head-to-foot direction. It is necessary to compress the breast during the examination to optimally image all the breast tissue, and this may cause mild to moderate discomfort.

A diagnostic mammogram uses many different views according to the patient’s specific problem. The most frequently used diagnostic views are magnification compression views for microcalcifications and spot compression views for mass or focal asymmetry. The technical aspects of mammography are very complicated, and it is extremely important that the mammographer be properly trained and qualified. Mammography quality controls are mandatory and regulated by the federal government under the Mammography Quality Standards Act of 1993.

Normal MLO and CC views of the breast are shown in Fig. 10.2. Notice that breast images are a combination of fat (black) and soft tissues (gray to white). This background of black and gray, especially the black, enhances visualization of the white calcifications and masses. Breast tissue is composed predominately of fibroglandular tissue in young women and gradually replaced with adipose tissue in older women.

GENERAL SCREENING MAMMOGRAPHY GUIDELINESa

1. Yearly mammograms are recommended starting at age 40; baseline before age 35 if mother or sister had premenopausal breast cancer. The age at which screening should be stopped should be individualized by considering the potential risks and benefits of screening in the context of overall health status and longevity. 2. Clinical breast examination should be part of a periodic health examination about every 3 years for women in their 20s and 30s and every year for women 40 and older. 3. Women should know how their breasts normally feel and report any breast change promptly to their health care providers. Breast self-examination is an option for women starting in their 20s. |

aScreening MRI is recommended for women with breast cancer (BRCA) gene mutation, women with an approximately 20%–25% or greater lifetime risk of breast cancer.

WHAT WE SHOULD SEE ON A MAMMOGRAM

Normal mammograms show a mixture of fat and fibroglandular tissue. Other normal structures such as blood vessels and lactiferous ducts are also seen. Lymph nodes are mainly seen in the axillary areas; however, they can also be seen within the breast parenchyma (intramammary lymph nodes). The two main mammographic findings suggesting abnormalities are masses and microcalcifications. Other abnormalities include focal asymmetry, architectural distortion, and skin or nipple deformity. Any structural changes over time require attention and further workup, unless otherwise explained such as surgical scar.

RISK FACTORS THAT CAN INFLUENCE THE TIMING FOR SCREENING MAMMOGRAPHY

1. Prior personal history of breast cancer 2. Family history of premenopausal breast cancer in mother, sister, or daughter 3. Presence of mutated BRCA-1 and/or BRCA-2 genes 4. Biopsy-confirmed atypical hyperplasia 5. Age (incidence increases with age) 6. Years of menstruation: early age menarche (<12 y), late age menopause (>55 y) 7. Nulliparous, late age first birth (>30 y) 8. Never breast-fed a child 9. Postmenopausal obesity 10. High-dose radiation to chest 11. Long-term use of hormone replacement therapy 12. Others |

The Breast Imaging Reporting and Data System (BIRADS) is a guideline developed by the American College of Radiology for radiologists to describe the mammographic findings, provide conclusions, and make appropriate recommendations for further workup in a well-structured manner. Initially, BIRADS was developed for mammography only; however, it now includes US and MRI according to a recently published version (4). The BIRADS guidelines are continuously revised and updated on the basis of experts’ opinions and evidence-based findings.

FIGURE 10.1 A: Illustration of how the patient is positioned for a mediolateral oblique (MLO) mammogram. The x-ray beam passes obliquely through the breast in a medial to lateral direction. The breast is routinely compressed between the compression device (straight arrows) and the radiographic cassette (curved arrow). The cassette contains a radiographic film on which the image will be recorded. Compression improves the diagnostic quality of the images by thinning the breast to a more homogeneous thickness. B: Illustration of how the patient is positioned for a craniocaudal (CC) mammogram. The x-ray beam passes through the breast in a head-to-foot or cephalad to caudad direction. The compression device (straight arrow) is more easily visualized in this illustration. Again, the image will be recorded on the film in the radiographic cassette (curved arrow).

FIGURE 10.2 A: Left breast mediolateral oblique (MLO) digital mammogram. Normal. B: Left breast craniocaudal (CC) digital mammogram. Normal.

Using BIRADS terminology, a mass seen on a mammogram is described in terms of its shape, border (margin), density, location, size, and associated findings. Associated findings may include microcalcifications and architectural distortion.

Benign disease (Table 10.3) may or may not be symptomatic or have associated masses. A fibroadenoma (Fig. 10.3) is a benign lesion that must be differentiated from a malignant mass. It generally occurs in young women and may be multiple or single. On physical examination, fibroadenomas are often movable. The mammographic appearance is an oval circumscribed mass sometimes associated with coarse “popcorn” calcifications. On sonography, these fibroadenomas will usually appear isoechoic.

Another common clinical problem is benign cystic disease. This problem occurs at all ages. Cysts may present as a palpable mass that may or may not be tender or an incidental mammographic finding. The mammographic appearance of a cyst is usually a mass of isodensity with well-defined sharp borders (Fig. 10.4A). Rarely, cysts have mural calcifications. Ultrasonography (Fig. 10.4B) usually shows a well-defined anechoic mass with posterior acoustic enhancement. Cysts may require aspiration depending on the clinical situation, and aspiration under US guidance is quite effective.

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree