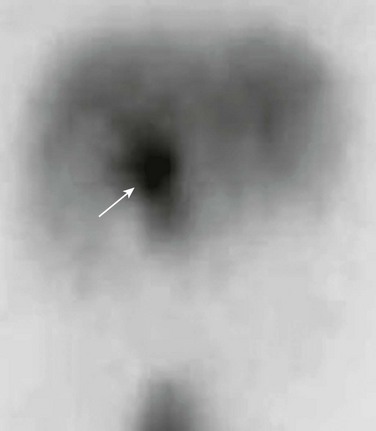

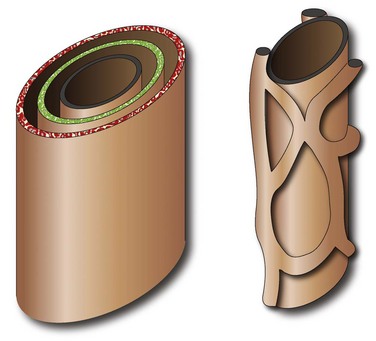

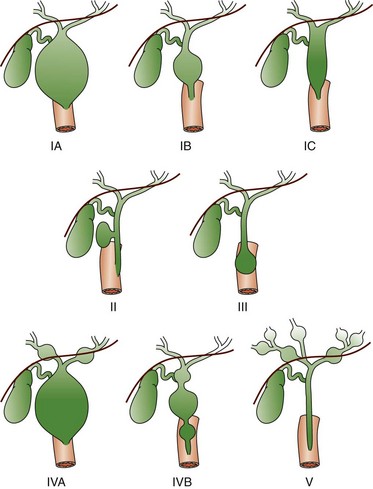

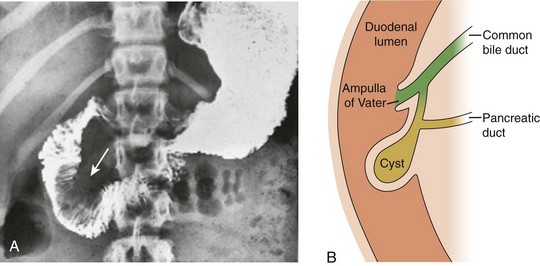

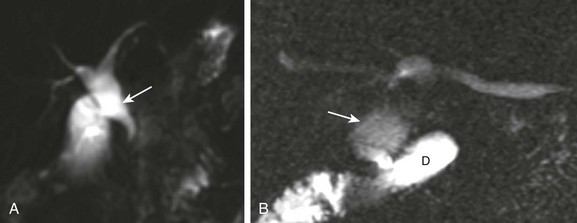

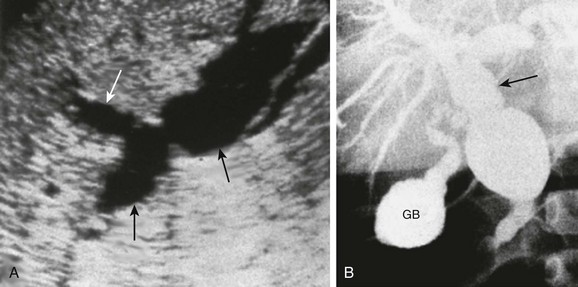

Chapter 88 Fibropolycystic liver disorders are a group of associated congenital anomalies of the liver caused by malformation of the embryonic ductal plates (Fig. 88-1). They include choledochal cysts, Caroli disease, hepatic fibrosis, biliary hamartomas, and cystic liver disease. The specific type of fibropolycystic disorder depends on the size of the embryonic duct with faulty development (Table 88-1). Table 88-1 Fibropolycystic Liver Disorder and Size of Ducts with Faulty Embryogenesis Figure 88-1 Schema of ductal plate. Overview: Choledochal cysts, which are among the most frequent of congenital hepatobiliary anomalies, are a fusiform or saccular dilation of the bile ducts. The Todani classification system is commonly used to categorize these anomalies into five general types (with several subtypes) that differ based on etiology, pathogenesis, appearance, and presentation (Fig. 88-2).1 Figure 88-2 Schematic of Todani classification of choledochal cysts based on cholangiographic morphology. The most common choledochal cyst is the Todani type I, found in 80% to 90% of cases.2 It involves variable lengths and degrees of common bile duct dilatation and is further classified into subtypes.2 Todani type IA, IB, and IC describe cystic dilation of the common bile duct, segmental dilation below the cystic duct, and fusiform dilation, respectively. Todani type II choledochal cysts are found in only 2% of cases and consist of one or more diverticula of the common bile duct.3 Todani type III occurs in 1.5% to 5% of cases and involves dilation of the intraduodenal portion of the duct, forming a cystlike mass, termed a “choledochocele,” with both the common bile and pancreatic ducts emptying into it. Todani type IVA consists of multiple intrahepatic and extrahepatic biliary dilatations and occurs in 10% of patients with choledochal cysts.1,3 Type IVB, which involves multiple extrahepatic biliary cysts without intrahepatic involvement, is rare. Todani type V is synonymous with Caroli disease.1 Todani type IVA also has been described as a type I cyst with intrahepatic involvement, and controversy exists about whether it is actually a type V (Caroli disease) cyst with common duct enlargement. Etiology: Several theories for the pathogenesis of the type I choledochal cysts exist. In addition to the ductal plate malformation described previously, other theories have suggested cyst formation as a result of obstruction of the distal biliary duct and/or reflux of pancreatic enzymes into the biliary tree because of anomalous proximal insertion of the pancreatic duct into the common bile duct (ductal malunion).4,5 This ductal malunion could permit reflux of pancreatic enzymes into the common bile duct, with subsequent inflammation and weakening of the wall, a pathologic mechanism that occurs in about 60% of patients.5 This anomalous ductal connection has been demonstrated on endoscopic retrograde cholangiopancreatography (ERCP) (Fig. 88-3). Type I choledochal cysts are more common in girls than in boys in Western countries, but the sex ratio is equal in Asia.2,3 About 65% of all reported cases are from Japan.2 It has been theorized that type II choledochal cysts result from prenatal rupture of the common bile duct with subsequent healing.3 Type III choledochal cysts may be the sequelae of ampullary obstruction or congenital duplication of the duodenum at the ampulla. The intrahepatic cysts seen in types IV and V are thought to be due to primary ductal ectasia resulting from ductal plate malformation. Clinical Presentation: Choledochal cysts may present in infancy with cholestatic jaundice, which clinically is inseparable from neonatal hepatitis or biliary atresia.2 In older children and young adults, the clinical presentation is variable. A characteristic triad of abdominal pain, obstructive jaundice, and fever has been reported, but few patients present with all three components. Abdominal pain is the most characteristic presentation, followed by obstructive jaundice, fever, pale stools, splenomegaly, hepatomegaly, and a palpable mass.6 The most common complication of a choledochal cyst is ascending cholangitis.7 Long-term complications, such as hepatic cirrhosis with subsequent portal hypertension, can occur.6 Carcinoma of the biliary tree has a twentyfold increased incidence in patients with choledochal cysts. This risk is low in the first decade but increases with advancing age.8 Spontaneous cyst rupture also has been reported.6 Imaging: When the clinical presentation points to a hepatobiliary problem, sonography usually is the initial imaging study requested. The markedly dilated common bile duct is readily discernible in types I and IV choledochal cysts. The gallbladder usually can be identified adjacent to the dilated common duct (Fig. 88-4). Most frequently, the intrahepatic ducts are normal, but varying degrees of dilation may be present as a result of obstruction. Sludge or stones may be identified within the dilated ducts.9 Type III cysts may cause mass effect at the ampulla of Vater (Fig. 88-5, A and B). Figure 88-4 Choledochal cyst (Todani type I) in an 8-day-old girl with jaundice. Figure 88-5 Choledochocele (Todani type III) in a 12-year-old girl with abdominal pain. Abdominal magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) with cholangiopancreatography (MRCP) often is performed to delineate anatomy (Fig. 88-6).10–12 Hepatobiliary scintigraphy can prove useful in difficult cases by demonstrating communication between the choledochal cyst and the hepatobiliary ducts (Fig. 88-7).9 Computed tomography (CT) does not demonstrate the biliary ductal anatomy as well as ultrasound and MRI, although it can be useful along with sonography to guide abscess drainage and to evaluate hepatic anatomy.10,11 Figure 88-6 A choledochal cyst (Todani type I). Percutaneous transhepatic cholangiography (PTC) and ERCP are useful when placement of a percutaneous biliary drain may be helpful (Fig. 88-8). Some investigators prefer PTC to ERCP because it carries a lower risk of iatrogenic cholangitis.7 Figure 88-8 Choledochal cyst (Todani type IV) in a 1-year-old boy. Treatment: Because of the potential long-term sequelae, surgical excision and hepatojejunostomy are performed as definitive treatments. Patients with intrahepatic cysts are closely monitored for cholangitis, cholestasis, and stone formation. Antibiotics are administered in the setting of acute cholangitis. Medical therapy can be instituted to reduce the risk of cholestasis and promote bile flow; however, when extensive liver damage and cirrhosis occurs, a liver transplant may be necessary. Overview: Caroli disease, also classified as Todani type V choledochal cyst, is a segmental nonobstructive dilation of the intrahepatic bile ducts. It is characterized by multiple hepatic cysts in continuity with the biliary system, representing ectatic intrahepatic ducts,7

Congenital Hepatobiliary Anomalies

Disorder

Duct Size

Congenital hepatic fibrosis

Small

Biliary hamartoma

Small

Polycystic liver disease

Medium

Choledochal cyst

Large extrahepatic

Caroli disease

Large intrahepatic

A bilayer of hepatocytes (green and red layers) surrounds the portal venous structures (central black), forming the lumina of primitive bile ducts (left). A process of organized resorption leads to the normal organization of biliary ducts within the portal triads. Failure of this process leads to ductal plate malformations.

Choledochal Cyst

Type IA and IB involve cystic dilatation of the common duct, with IB limited to the area below the insertion of the cystic duct; IC is fusiform dilatation of the duct. Type II is a saccular diverticulum from the common bile duct, and type III is a choledochocele at the ampulla of Vater. Types IVA and IVB are multiple cystic dilations of the intrahepatic and extrahepatic biliary tree, and type V is equivalent to Caroli disease with numerous intrahepatic bile lakes throughout the biliary tree and liver. (From Kim OH, Chung HJ, Choi BG. Imaging of the choledochal cyst. Radiographics. 1995;15:69-88.)

Transverse sonogram shows a large fusiform cyst in the porta hepatis (asterisk) just beneath a small, contracted sludge filled gallbladder (arrow).

A, Upper gastrointestinal tract image shows a large filling defect (arrow) coincident with the site of the Ampulla of Vater. B, Drawing of findings of choledochocele confirmed at surgery.

A, Magnetic resonance imaging with cholangiopancreatography (MRCP) in a 10-day-old boy with jaundice demonstrates dilatation of the common bile duct (arrow). B, A choledochal cyst (Todani type I) in a 6-year-old boy with abdominal pain. MRCP reveals dilation of the common bile duct (arrow) draining into the normal duodenum (D).

A, A longitudinal sonogram shows marked saccular dilation of the intrahepatic and extrahepatic bile ducts (arrows). B, An operative cholangiogram confirms dilation of the intrahepatic biliary tree and common bile duct (arrow). The gallbladder (GB) is noted.

Caroli Disease and Caroli Syndrome

![]()

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree