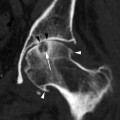

Fig. 2.1

Chest radiography. (a) Occasional finding of inveterate dislocation of the right shoulder. The CT states the skeletal situation (b, c) and shows the presence of extensive collection (d, e)

Fig. 2.2

Clinical algorithm in elderly with musculoskeletal pain

In recent years, collaboration among physicians, such as geriatricians, orthopedists, and radiologists, has much improved our knowledge of the multifactorial etiology of pain. Consequently, modern diagnostic imaging must consider the most common clinical manifestations of the “healthy” and the “ill” elderly. Because the pathologies of old age are often different than those in younger adults, identifying the etiology of pain (often multifactorial) in the elderly, by use of geriatric assessment and retrospective history of the patient, is nowadays “the challenge” for modern radiologists. It should be noted that in the elderly comorbidity, defined as co-occurrence of multiple chronic conditions (Ferrucci et al. 2008), is common and can make the clinical diagnosis of musculoskeletal disorders difficult (Van Schaardenburg et al. 1994). Symptoms may be caused by a set of conditions in the musculoskeletal system or in other organs and can mask the clinical manifestations of uncommon pathologies. In particular, in one of two patients with a rheumatic disease, at least one other chronic condition will be diagnosed (Van Schaardenburg et al. 1994). The coexistence of multiple pathologies also involving the musculoskeletal system causes a significant reduction in quality of life and can lead to serious disability.

A large proportion of elder people suffer chronic joint symptoms (Ferrucci et al. 2008); these can cause major functional limitations, considering only the musculoskeletal system, and most commonly affect the shoulder joint. Frequently, the disability is related to other concomitant afflictions: in a Dutch community survey, a walking disability, defined as an inability to walk at least 500 m, was found in 60 % of the subjects over 85 years old. According to the report, hip and knee osteoarthritis, impaired vision, cognitive impairment, and neurological disease were the main causes of disability (Van Lankveld et al. 2005).

Cancer is the second leading cause of death in the USA and epidemiologists estimate that in the next few years it will exceed the current leader, heart disease (Berger et al. 2006; Muss 2009).

The incidence of cancer increases with age: skeletal metastases are the most common malignant bone tumor. In woman the primary cancer is most frequently in the breast, and in men the primary cancer is in the prostate. They are followed, by frequency of bone metastases, by malignant tumors of the lung, kidney, thyroid, gastrointestinal tract, bladder, and skin (Cheong et al. 2008).

In the elderly population of the USA, Europe, and Japan, cancer mortality has stopped its long-term rise; multiple myeloma is the exception. It is estimated that 20 % of both men and women aged 65–84 will be affected by multiple myeloma (Levi et al. 2001).

In old age the incidence of multiple myeloma, malignant bone marrow cancer, is high. It can present with bone lesions (Fig. 2.3): imaging findings are critical to the diagnosis, classification, and clinical follow-up. Other oncohematologic disorders, like CCL (chronic lymphatic leukemia), aplastic anemia, and osteomyelofibrosis/osteomyelosclerosis, may affect the elderly with high or moderate degree of bone impairment (Baur-Melnyk and Reiser 2008).

Fig. 2.3

Multiple myeloma lesions. Pelvis radiography (a). Right arm radiography (b) shows a pathological fracture. Spine CT: coronal (c, d) and sagittal (e, f) reformatted. Spine scans: MRI: STIR (g), T2W FRFSE (h), T1W SE (i), T2W FRFSE (j), STIR (k), T1W SE (l)

The radiologist must be cautious in making the association between clinical history and imaging: a bone replacement lesion in a patient with a previous cancer should not lead one to diagnose a metastasis. In addition to the bone oncohematologic lesions, there are also chondrosarcomas, which are frequent in the elderly but do not always have typical imaging features (Baur-Melnyk and Reiser 2008; Cheong et al. 2008).

Paget disease is usually diagnosed before an advanced age; but because of its slow progression, this condition is often seen in geriatric patients: bone changes are often asymptomatic and are found incidentally (Cheong et al. 2008).

Genetics, hormonal balance, renal function, and lifestyle all contribute to the development of osteoporosis in the elderly: the bone is frailer due to an altered balance between production and resorption and its calcium content reduced, increasing the risk of fractures (Guglielmi et al. 2006, 2008).

Paradoxically, the calcium is deposited in many normally non-calcified structures (Fig. 2.4). Extra skeletal calcifications of vascular walls, ligament insertions, chondral portions of ribs, elaioma, and other sites are quite common in the elderly. These calcified structures can overlap on bone lesions in conventional radiography. They may not even be visible, or they may require many exposures in different views to be seen.

Fig. 2.4

(a, b) Right knee radiography shows the presence of meniscus and ligament calcifications in chondrocalcinosis

Diagnostic procedures can also be used also to guide interventional therapy. Therapy can often substitute for surgery or at least mitigate the surgical approach. Any invasive procedure will be less well tolerated by the elderly, especially if there are comorbidities. Many interventional radiology techniques require only local anesthesia or none at all.

2.2.2 Technical Choices

The elderly patient suffering from a musculoskeletal pathology can be a fragile subject from a psychological perspective, requiring special care. Discomfort, due to medical conditions, especially pain, is often increased by the difficulty of communicating caused by the common disabilities of old age: diminished hearing and seeing, difficulty in expressing oneself, or lack of physical coordination. The medical and paramedical staff caring for the elderly patient should work to reduce any psychological trauma. The professionalism of the imaging department team necessitates empathy: in listening to the problems reported by the patient and explaining in a simple way the procedures to be performed while fully respecting the patient’s privacy and dignity (Ferrucci et al. 2003; Serraino et al. 2001).

The Radiological Society of North America (RSNA) has published guidelines, based on diagnostic and interventional radiology, medical physics, nuclear medicine, radiation oncology, ultrasound, and MR imaging, for choosing the best techniques for use in different clinical situations (RSNA 2011). Based on the clinical characteristics of elderly patients, the first diagnostic level is plain radiography, which is widely available and relatively inexpensive (Fig. 2.5). Unfortunately in geriatric patients, radiography may be difficult: correct positioning may require devices, more or less stiff, to assure correct posture and immobilization. Mobile x-ray equipment with high-quality digital panels and radiolucent beds and gurneys are useful to avoid unnecessary movement for the patient.

Fig. 2.5

Pelvis radiography: occasional finding of inveterate pseudoarthrosis of an unrecognized fracture of the right femoral neck, in a patient with dementia

With regard to radiation protection, the elderly do have one advantage in that there is no need to be concerned with pregnancy or the effects of radiation on offspring. The elderly are often subjected, however, to numerous and repeated studies of different anatomical sites. Digital radiology (DR) is to be preferred to conventional techniques: thanks to post-processing, digital capture allows assessment with a single exposure to radiations of bone and soft tissue injuries that are characterized by different levels of radiopacity. Window and contrast level can be manipulated to evaluate the osteoporotic bone with a focused study during the reading.

With regard to the technical exposure data (mAs and kV), techniques that assure a rapid acquisition are to be preferred, not only to avoid breath and movement artifacts, but because elderly people often cannot hear instructions or cannot collaborate because of impaired mental status (Cáceres 2005).

Due to the difficulty of localizing exactly the site of pain because of preexisting algological pathologies, diagnostic procedures on the musculoskeletal system may be more extended. Panoramic radiographs are preferable to targeted x-rays, at least during the initial diagnosis (e.g., pelvis rather than a single hip).

Plain radiography remains the only imaging technique that allows functional study under loading, as standing is the most common physiological situation for humans (Guglielmi et al. 2006). Imaging the patient while standing allows full display of the limbs and spine in two orthogonal projections, which is useful for preoperative evaluation. In fact, it is essential for surgical planning and the choice of prosthetic material to know the position and spatial relations of the structures with a precise evaluation of the size, axis, and angles under load (Fig. 2.6).

Fig. 2.6

Knee radiological study to plan prosthetic surgery: comparative frontal (a) and lateral views (b); axial patellar projection (c) and teleradiography in orthostasis of the whole limb (d)

Ultrasound (US) of joints, muscles, and tendons is normally well accepted by elderly subjects; this technique allows repeated control and may also be performed in the emergency room or at the bedside. B-mode echography may be complemented in the same session by color- and power-Doppler studies of the focalized musculoskeletal lesions; CUS (compression ultrasound) or color Doppler to complete an arteriovenous study of a limb can be performed to evaluate associated vascular problems.

During dynamic imaging with CEUS (contrast-enhanced ultrasound), intravenous contrast media can be used for typing of soft tissue expansive juxta-skeletal lesions or to assess the extent of traumatic muscle injury and the subsequent repair process. The contrast media is made of elastic gaseous microbubbles that remain in the vascular bed and do not reach extravascular spaces, and they are safe for use in the elderly patients too, except in the presence of serious heart disease.

QUS (quantitative ultrasound) and DXA (dual-emission x-ray absorptiometry) are used for qualitative and quantitative evaluation of bone. Five risk factors are considered predictors of osteoporotic fracture: four clinical factors – old age, history of fracture, a failed chair test, a recent fall – and the low heel qualitative US stiffness index (Guessos et al. 2008). DXA quantitative determination of bone mineral density (BMD) is a reliable means to improve accuracy in osteoporosis screening and fracture risk. The WHO classification of osteoporosis is based on the T-score (difference of BMD against a standard young adult population) and the Z-score (difference of BMD against the mean of race-, age-, and gender-matched controls). In the elderly, the Z-score is more important; however in very old subjects, the Z-score cannot be determined because there have been no studies of large populations of the elderly for reference yet. The choice of the site of BMD evaluation is important: in the elderly the proximal femur up to the lumbar spine is to be preferred, because vertebral degenerative calcifications may falsify the measurement. Recent studies stress the importance of body composition and body mass index (BMI) as complements to bone mass density (BMD) in elderly patients (Andreoli et al. 2011).

An interesting application of DXA is the study of juxta-prosthesis bone in hip replacement to help diagnose after-surgery complications.

Vertebral morphometry, which can assure precise and comparable measurements of vertebral body deformation, is easier to realize with DXA than with radiography, because it is not necessary to move the patient from the supine to the lateral decubitus position (Guglielmi et al. 2008).

QCT (quantitative computed tomography) is a very precise method to evaluate bone density in vertebral sites because the operator can select the areas of interest to be measured, choosing only trabecular bone with more metabolic turnover than the surrounding cortical bone (Guglielmi et al. 2008).

Diagnostic examinations that require a long time in a stationary decubitus position are often unsuitable to the elderly patient, especially if he or she is left alone in the room and placed in a complex diagnostic equipment, such as during CT and MRI examinations. The elderly may have difficulty understanding the course of the procedure and the information must be provided in a simple way: beepers or lights can be used to communicate with the patient. The patient’s position on the scanning table should be as comfortable as possible, remembering that long periods on hard surfaces can promote pressure ulcers in specific areas of the body (e.g., the heel), especially if the tissues are hypotrophic and poorly vascularized, as they frequently are in the elderly. In debilitated patients, permanent tissue damage can occur in less than 2 h; pressure ulcers form where soft tissues are compressed between a bony prominence and a hard surface, with a microthrombosis mechanism.

In addition, logistical problems often overlap: radiology facilities may be far from the elderly person’s home or hospital room and the subject has to be accompanied or transported with extensive involvement of relatives or assisting staff (Cáceres 2005). Delays and abnormal life rhythms are also to be taken into account. The use of MDCT (multidetector computed tomography) shortens the examination and presumably minimizes discomfort (Cáceres 2005). Regarding CT and MRI, acquisition with large field of view is recommended. The wide field of view allows more information to be gained from post-processing reformatting, though such techniques are beyond the scope of this chapter.

Particular attention must be paid in cancer diagnostics: the correlation of imaging data and laboratory values is critical to differentiate multiple myeloma bone lesions from skeletal metastatic disease. A whole body MDCT may be performed in these cases with a low-dose protocol, thanks to the technique’s high contrast between bone and soft tissue. MRI use is indicated to detect pattern and degree of bone marrow infiltration, which is useful for setting and monitoring the correct treatment (Baur-Melnyk and Reiser 2008). The diagnostic process can be completed with PET-CT (positron emission tomography–computed tomography).

MRI is highly reliable in the study of anatomical components of the joints and can be supplemented with intra-joint contrast medium. MRI also allows a panoramic assessment of the musculoskeletal structures. These characteristics make MRI quite useful in surgical planning.

Artifacts from metallic implants, often present in the elderly patient, can limit the optimization of CT and MRI images. Especially for CT, careful planning of the specific technical parameters in the execution of the exam and the use of dedicated reformatting programs allow a complete and correct diagnosis. The use of “open”- or low-field MRI equipment, dedicated to the study of the limbs, makes it possible to study patients with claustrophobia or mental health problems who cannot tolerate the positioning in traditional high-field instruments, thus avoiding the need for anesthesia. If the patient has a cardiac pacemaker, CT must be used in lieu of MRI.

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree