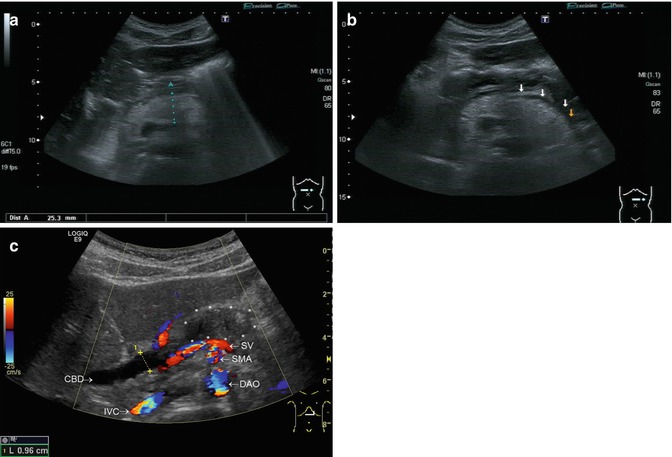

Fig. 8.1

(a) A 15-year-old girl with symptoms of angina abdominalis. US investigation 3 years after resection and radiation of a rhabdomyosarcoma in the retroperitoneum between the coeliac trunk and the superior mesenteric artery. Doppler sonography was only possible in this patient with persistent massive meteorism after drinking water with a thick drinking straw in order to fill the stomach as an US window and right decubitus position. CDS artefacts within the water-filled stomach. The aorta, coeliac trunk and superior mesenteric artery can now be visualised. Longitudinal section through the upper abdomen in the right decubitus position. (b) Same patient. Mild stenosis of the superior mesenteric artery after surgery and radiation of a rhabdomyosarcoma. The flow velocity in the PW-DS is elevated (normal limit <1.5 m/s). Longitudinal section through the upper abdomen in the right decubitus position

8.2 Normal Findings

8.2.1 Embryology of the Pancreas and Inborn Anomalies

The pancreas originates from fusion of the ventral bud and dorsal bud. The ventral bud later forms a part of the head and the uncinate process of the pancreas, whereas the dorsal bud forms most of the rest of the pancreas. The pancreas has a lobulated appearance. Occasionally, lobulations may be marked and have to be distinguished from a mass. The major pancreatic duct (duct of Wirsung) of the former ventral bud usually connects with Santorini’s duct of the former dorsal bud and drains into the major papilla. The accessory minor duct (Santorini’s duct) of the dorsal bud either obliterates or drains into the minor papilla.

In cases of incomplete fusion, a pancreas divisum (Fig. 8.2a, b) results, the most common pancreatic anomaly (4–14 % in autopsy studies), which usually remains asymptomatic (Yu et al. 2006; Rana et al. 2012). In patients with pancreas divisum, the accessory minor duct (Santorini’s duct) always persists and drains most of the pancreatic secretions. A relative stenosis of the accessory minor duct is thought to be responsible for the higher incidence of recurrent pancreatitis in these patients. In US, a prominent pancreatic head and possibly two pancreatic ducts in the head of the pancreas may be seen. The final diagnosis of a pancreas divisum, however, is made by ERCP or MRCP. A cystic dilatation of Santorini’s duct proximally to the minor papilla (“santorinicele”) may be present. If the ventral part of the embryonic pancreas remains in front of the duodenum, an annular pancreas results and leads to a ring of pancreatic tissue around the duodenum. The incidence of annular pancreas with the typical radiological double-bubble sign is far less frequent than a pancreas divisum. Most infants with duodenal atresia have an annular pancreas. Patients may be asymptomatic; possible complications are duodenal obstruction, pancreatitis, postbulbar ulcerations or biliary obstruction. Rarely, branching anomalies of the pancreatic tail result in a bifid (“fishtail”) pancreas.

Fig. 8.2

Pancreas divisum. (a) B-mode US shows an enlarged pancreatic head, a lobulated surface and a marked pancreatic incision seen as a discontinuation of the ventral surface between the head and corpus of the pancreas. Cross section through the upper abdomen. (b) Pancreas divisum in a 12-year-old boy with recurrent pancreatitis. Two parallel pancreatic ducts can be seen in the pancreatic body. Cross section through the upper abdomen

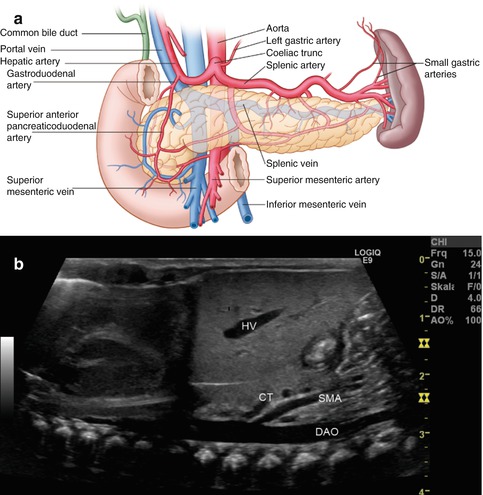

8.2.2 Pancreatic Vascular Anatomy

The arterial supply of the pancreas derives from branches of the coeliac trunk, the splenic artery and the superior mesenteric artery (Fig. 8.3a, b). The splenic artery supplies the former dorsal pancreatic bud with ten small branches to the corpus and tail of the pancreas. They form a network of arterial arcades with branches from the gastroduodenal artery and the superior mesenteric artery. The superior and inferior pancreaticoduodenal arteries are branches of the gastroduodenal artery (a branch of the common hepatic artery) and supply the head of the pancreas.

Fig. 8.3

(a) Scheme of the arterial blood supply of the pancreas. (Drawing by Blankvisual, Thun, Switzerland). (b) The first branch from the descending aorta (DAO) is the coeliac trunk (CT), the second the superior mesenteric artery (SMA). Both vessels are located dorsally of the pancreas. The coeliac trunk lies more cranially than the pancreatic body. Longitudinal section through the thoracic and abdominal aorta in a newborn. HV hepatic vein

The branches of the pancreatic veins drain directly into the splenic vein, which is embedded in the back of the pancreas.

8.2.3 Ultrasonographic Approach

The pancreas is located completely in the retroperitoneum and shows nearly no movements during deep respiration. Sitting or standing positions and deep inspiration shift the liver in front of the pancreas. This creates an acoustic window and helps to optimise visualisation of the pancreas (Sienz et al. 2011).

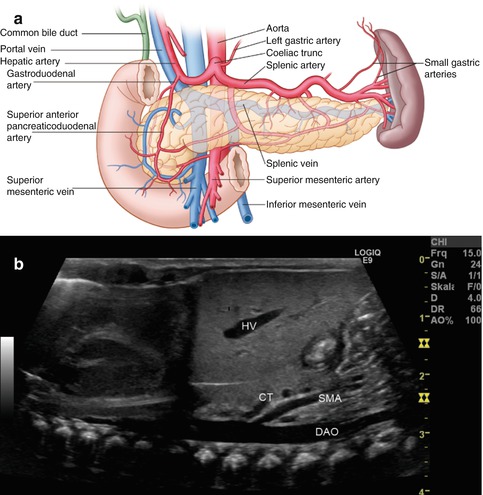

The pancreas has very close topographic relations to all upper abdominal vessels and is embedded by the coeliac trunk cranially and the superior mesenteric artery and vein, the aorta, inferior vena cava and right and left renal vein dorsally (Fig. 8.4a–d). At first, an appropriate identification of the pancreas and its vascular landmarks is necessary before starting Doppler sonography.

Fig. 8.4

Normal vascular anatomy. 2D ultrasonography. (a) The main abdominal vessels neighbouring the pancreas are shown: dorsally the inferior vena cava (IVC) on the right and the abdominal aorta (DAO) on the left patient’s side. The left renal artery (LRA) leaves the aorta to the left, and further ventrally the left renal vein (LRV) can be seen along its full course ventrally to the aorta and underneath the superior mesenteric artery (SMA) to the inferior vena cava. The splenic vein (SV) is located directly dorsally to the pancreatic body and tail. Cross sections through the upper abdomen. (b) The coeliac trunk (CT) is the first abdominal branch from the descending aorta (DAO) and is located more cranially than the pancreas in a cross section through the abdomen. Typical “palm tree” appearance with the common hepatic artery (HA) leaving to the patient’s right side and the splenic artery (SA) leaving to the left. Cross sections through the upper abdomen. GB gall bladder, IVC inferior vena cava, PV portal vein. (c) The superior mesenteric vein (SMV) can be visualised dorsally of the pancreas until forming the splenoportal confluence together with the splenic vein. Longitudinal section through the upper abdomen. SA splenic artery. (d) Topographic ultrasonographic anatomy of the superior mesenteric artery (SMA) and vein (SMV) dorsal of the pancreas. Longitudinal section through the upper abdomen

The mesenteric artery and vein are situated dorsally of the uncinate of the pancreas in the pancreatic indentation, which lies between the pancreatic head and body (Figs. 8.5 and 8.6). The splenic artery runs along the cranial pancreatic border towards the splenic hilus and is located partly retro- and partly intraperitoneally. The splenic vein is located more caudally of the artery and is the main leading structure for the sonographic visualisation of the pancreas (Fig. 8.6a, b).

Fig. 8.5

The splenic vein (SV) is located more caudally of the artery (SA) and is the main leading structure for the sonographic visualisation of the pancreas. Cross section through the upper abdomen. CDS of the splenic vein (SV) and artery (SA); DAO descending aorta. (Drawing by Blankvisual, Thun, Switzerland)

Fig. 8.6

The splenic vein is located more caudally of the artery and is the main leading structure for the sonographic visualisation of the pancreas. (a) Cross section through the upper abdomen. The splenic vein (SV) can be seen all along the posterior border of the pancreatic body and tail. DAO descending aorta, IVC inferior vena cava, SMA superior mesenteric artery, SV splenic vein. (b) Cross section through the upper abdomen in a 14-year-old boy. CDS shows the splenic vein (SV) dorsal of the pancreas. DAO descending aorta, SPC splenoportal confluence

DS can usually hardly visualise the gastroduodenal artery as it runs dorsally to the duodenal bulb; its branches (superior and inferior pancreaticoduodenal arteries and anterior and posterior branches) may be seen as small dots within the head of the pancreas (Bertolotto et al. 2007) (Fig. 8.7).

Fig. 8.7

Longitudinal section through the upper right abdomen with sensitive flow settings. Branches of the superior and inferior pancreaticoduodenal arteries may be seen as small dots in the head of the pancreas (↓). SMA superior mesenteric artery, SMV superior mesenteric vein

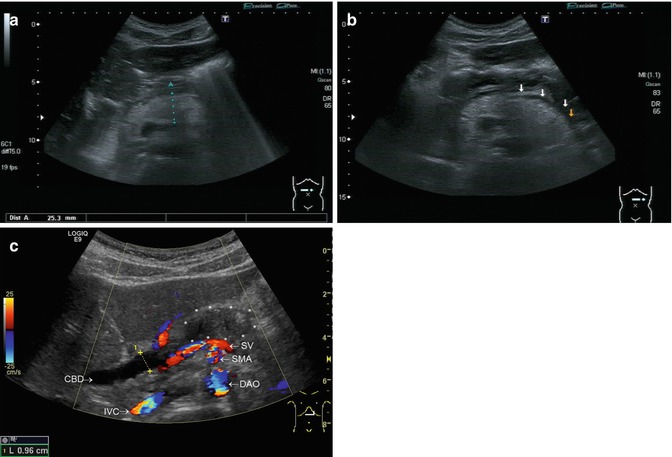

Colour and spectral Doppler (CDS and PW-DS) aim to demonstrate the large upper abdominal vessels around the pancreas or vascular alterations such as aneurysms of pancreatic vessels, which are extremely rare in children. Hyperperfusion of the pancreas with prominent intraparenchymal vessels may be detected if sensitive flow settings are chosen (Fig. 8.8a–c).

Fig. 8.8

Enlargement and hyperperfusion of the pancreas with prominent intraparenchymal vessels in a 7-year-old boy with acute myeloic leukaemia. (a) B-mode of the enlarged pancreatic head (3.63 cm depth × 3.85 cm width). Transverse section through the upper abdomen. (b) Small vessels within the pancreatic parenchyma can be visualised by CDS. The splenic vein and the splenic artery are located cranially of the pancreatic tail. On the right side of the image, the renal vein and artery are shown. Left longitudinal section through the spleen and tail of the pancreas. (c) Same patient. Enlarged and slightly hypervascularised peripancreatic lymph nodes (lymph node length 2 cm). Cross section through the upper abdomen

The approach of applying colour-coded Doppler sonography (CDS) and pulsed-wave Doppler sonography (PW-DS) in the great abdominal vessels are described in the hepatic, splenic and general sections of this book.

Main indications for Doppler sonography (DS) of the pancreas are listed in Table 8.1.

Table 8.1

Indications for Doppler sonography of the pancreas

Acute and chronic pancreatitis |

Trauma |

Screening in abdominal pain |

Focal and diffuse lesions |

Pancreas transplantation |

Disorders of the neighbouring vessels |

Diffuse and focal alterations of the pancreas have to be differentiated.

8.3 Doppler Sonography in Pancreatitis and Diffuse Lesions

8.3.1 Introduction

The most common diffuse changes are related to acute (Fig. 8.9a–c) and chronic (Fig. 8.10a, b) pancreatitis, involvement in inflammatory and systemic diseases such as cystic fibrosis, Shwachman-Diamond syndrome (Fig. 8.11) or haemochromatosis, which eventually lead to pancreatic malfunction, lipomatosis and atrophy.

Fig. 8.9

Acute pancreatitis. Transverse sections through the upper abdomen. (a) Enlarged and hyperechoic pancreas (diameter of the pancreatic body 2.5 cm) in a child with acute episode of recurrent pancreatitis. (b) Fluid collection along the pancreatic tail in a child with acute oedematous episode of recurrent pancreatitis marked by arrows. (c) A 12-year-old boy with the first episode of autoimmune pancreatitis. Enlarged pancreatic head , dilated common bile duct (0.96 cm) (CBD). With CDS the descending aorta (DAO), superior mesenteric artery (SMA) and the splenic vein (SV) are seen dorsally of the pancreas , inferior vena cava (IVC). Due to the low Nyquist limit of CDS, the flow is displayed in a mosaic pattern (aliasing). CDS helps to distinguish vessels and not perfused structures

Fig. 8.10

Chronic pancreatitis. Transverse sections through the upper abdomen. (a) Adolescent with chronic pancreatitis, reduced pancreatic parenchyma, irregular and grossly dilated pancreatic duct (PD). SV splenic vein, SMA superior mesenteric artery, DAO descending aorta. (b) Chronic pancreatitis. Irregular and inhomogeneous pancreatic parenchyma. The pancreatic borders can hardly be distinguished from the surrounding tissue and are marked with arrows

Fig. 8.11

Shwachman-Diamond syndrome. Enlarged pancreas with inhomogeneous and course parenchyma. Transverse section through the upper abdomen

In all of these conditions, Doppler sonography (DS) does not play a major role for establishing an ultrasonographic diagnosis but contributes in distinguishing perfused from non-perfused structures in the pancreatic area (Fig. 8.12) (Koito et al. 2001). As ultrasonography (US) is non-invasive, mobile, has no radiation burden and low cost, it is the first-line imaging method of the pancreas (Nürnberg et al. 2007).

Fig. 8.12

Large haemangioma within the duodenal wall. Doppler sonography (DS) contributes in distinguishing perfused from non-perfused structures in the pancreatic area. Transverse section through the upper abdomen. pancreas

8.3.2 Acute, Chronic and Idiopathic Fibrosing Pancreatitis

The causes of pancreatitis in children are much more wide-ranging than in adults and include gallstones, trauma, choledochal cysts, pancreas anomalies, side effect of drugs, metabolic disorders, pancreatic involvement in haemolytic uraemic syndrome, viral infections, autoimmune and hereditary pancreatitis. Parts of the pancreas or the whole organ can be involved (Nürnberg et al. 2007) in acute or chronic pancreatitis. Focal pancreatitis can be mass-forming and difficult to distinguish from pancreatic tumours (Low et al. 2011).

US signs of acute pancreatitis are lowered echogenicity (Fig. 8.13a), organ enlargement and in severe cases ill-defined borders. Especially in autoimmune pancreatitis, enlarged regional lymph nodes may be present. Calculi in the common biliary duct close to the major papilla have to be looked for as a possible cause of acute pancreatitis (Fig. 8.13b). The diagnostic help of the “twinkling artefact” in the diagnosis of stones is usually reduced by superimposed intestinal gas. A rare cause of acute pancreatitis is a wandering spleen (Magno et al. 2011). Doppler sonography may predict a severe case of pancreatitis by high splanchnic vascular resistance and higher resistance indices in the coeliac trunk and the superior mesenteric artery (Topal et al. 2008). In necrotising pancreatitis, there may be cystic degeneration and abscess formation. Further complications of pancreatitis are formations of pseudocysts (Fig. 8.14), which may need drainage. Vascular complications such as thrombosis of the splenic or portal vein or pseudoaneurysms of the hepatic artery may occur (Janarthanan et al. 2012; Bertolotto et al. 2007). The latter can safely be diagnosed by DS. Calcification may be present after pancreatitis, which may additionally be identified by the Doppler sonographic “twinkling artefact”.

Fig. 8.13

(a) Acute pancreatitis in a 12-year-old child with Crohn’s colitis and azathioprine treatment. Compared to the liver, the pancreas shows a marked lowered echogenicity and organ enlargement. Longitudinal section through the upper abdomen. (b) Concrements in the common biliary duct close to the major papilla have to be looked for as a possible cause of acute pancreatitis. A 16-year-old boy with a concrement close to the papilla. No concrements in the gall bladder. The common bile duct is widened. Right intercostal oblique section

Fig. 8.14

Pancreatic pseudocysts in the pancreatic tail in a patient with cystic fibrosis. Left intercostal oblique section

Autoimmune pancreatitis accounts for 25 % of all cases of focal pancreatitis and may be successfully treated with corticosteroids (Fig. 8.15a–c). Autoimmune pancreatitis is characterised by lymphoplasmacytic infiltration, increased IgG4 blood levels and positive IgG4 staining in cyto-or histopathology. There is an association with other autoimmune diseases such as primary sclerosing cholangitis or an atopic history. In US, autoimmune pancreatitis usually presents with pancreatic enlargement. In ongoing disease, a loss of visualisation of the pancreatic duct and a rim-like capsule due to fibrosis can be seen (Low et al. 2011). DS usually adds no further diagnostically relevant information. Calcification has rarely been seen (Hocke et al. 2011). Contrast-enhanced endoscopic ultrasonography was shown to be of diagnostic value in distinguishing lesions caused by autoimmune pancreatitis from pancreatic tumours (Hocke et al. 2011) by unique vascularisation pattern with a net-like hypervascularisation of the surrounding pancreas using intravenous contrast agents.

Fig. 8.15

Patients with autoimmune pancreatitis. (a) The dilated common bile duct can be distinguished from the hepatic artery and the portal vein by CDS. Right intercostal oblique section. (b) Enlargement of the pancreatic head, sludge in the gall bladder. Transverse section through the upper abdomen. (c) Intrapancreatic small lymph node within the pancreatic corpus. Transverse section through the upper abdomen

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree