hCG (mIU/mL)

# (202)

%

Third–Fourth international standard

<1000

162

80.2

1000–1499

19

9.4

1500–1999

12

5.9

≥2000

9

4.5

hCG (mIU/mL) | Gestational Sac | Yolk Sac | Embryo |

|---|---|---|---|

Threshold level | 390 | 1094 | 1394 |

Discriminatory level | 3510 | 17,716 | 47,685 |

Endometrial Findings in Ectopic Pregnancy

Endometrial Thickness

When a gestational sac or yolk sac are not visualized, endometrial thickness may be helpful in assessing the location of a pregnancy. Spandorfer and Barnhart reviewed the ultrasound measured endometrial thickness in patients with a hCG below the discriminatory level. In general, an IUP had a mean endometrial thickness that was greater than an EP or a spontaneous miscarriage (13.42 mm vs. 5.95 mm vs. 9.28 mm, respectively) [14]. In their study, an endometrial thickness ≤ 8 mm was associated with an abnormal pregnancy in 97 % of cases. Thus, when evaluating early pregnancy, a thicker endometrium may be more commonly associated with an IUP, while a thinner endometrium is more common with an EP (Figs. 16.1 and 16.2).

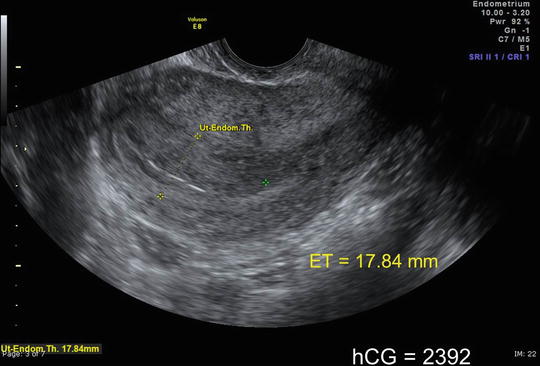

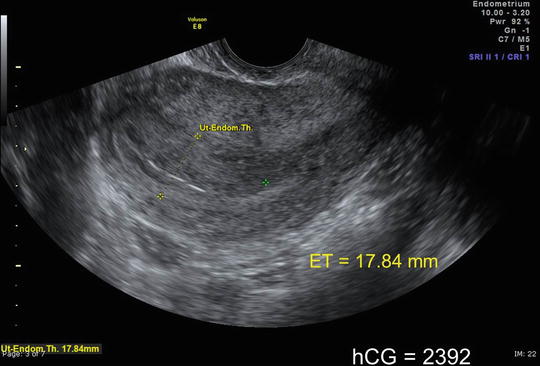

Fig. 16.1

Thicker endometrium (17.84 mm) in an early intrauterine pregnancy

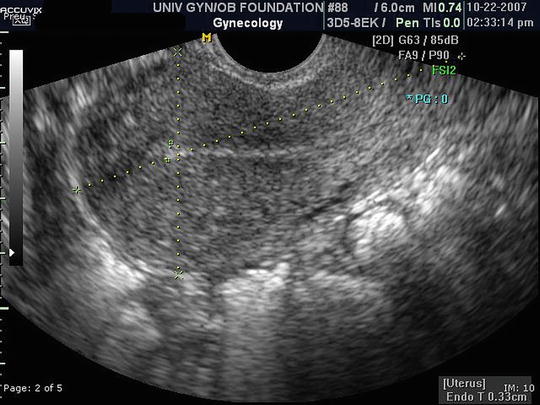

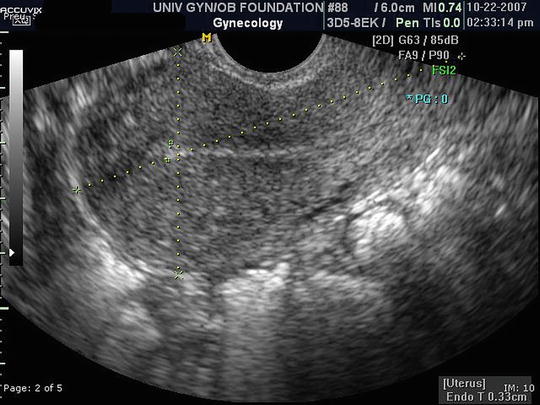

Fig. 16.2

Thin endometrium (3.3 mm) associated with an ectopic pregnancy

Intrauterine Fluid

The characteristics and shape of the intrauterine fluid in early pregnancy helps determine a pregnancy’s location. Benson et al. determined that no intrauterine fluid was present in 83.4 % of patients with an EP (191 of 229) [15]. Furthermore, 86.8 % of those patients with an EP and intrauterine fluid (33 of 38), also had an adnexal mass. In most of these patients (31 of 38, or 81.6 %), the fluid that was present tended to follow the contour of the endometrial cavity (Fig. 16.3). A smaller number (7 of 38, or 18.4 %) had a smooth walled cyst-like structure within the uterus. Such a cystic fluid collection can mimic an IUP. The differentiation is that the gestational sac of an IUP burrows into the decidua and is located slightly eccentrically (Fig. 16.4). One of the most important findings of this study was that a smooth-walled anechoic intrauterine cystic structure with no identified adnexal mass is associated with an IUP in 99.8 % of patients (Fig. 16.5).

Fig. 16.3

Intrauterine fluid with low-level echoes following the endometrial contour in patient with an ectopic pregnancy

Fig. 16.4

Gestational sac located in the posterior endometrium in an early intrauterine pregnancy

Fig. 16.5

Smooth-walled anechoic sac in a patient with an early IUP

Adnexal Findings in Ectopic Pregnancy

In 1994, Brown and Doubilet reviewed ten studies with over 2000 patients with suspected EP to determine the adnexal findings associated with an ectopic pregnancy [16]. All ectopic pregnancies were surgically confirmed. They determined the following four categories of adnexal findings associated with ectopic pregnancies:

1.

An adnexal embryo with a heartbeat (Fig. 16.6);

Fig. 16.6

Adnexal embryo with FHR = 172 which is diagnostic of an ectopic pregnancy

2.

An adnexal mass with a yolk sac and no embryonic cardiac activity (Fig. 16.7);

Fig. 16.7

Adnexal mass with a yolk sac which is diagnostic of an ectopic pregnancy

3.

An adnexal mass with a central anechoic area with a hyperechoic ring (“tubal ring” or the “bagel sign”) (Fig. 16.8); and

Fig. 16.8

“Tubal ring,” or so-called “bagel sign” in an ectopic pregnancy

4.

Any adnexal mass, other than a simple cyst or an intraovarian lesion (Fig. 16.9).

Fig. 16.9

Adnexal mass separate from the ovary in an ectopic pregnancy

The first two findings are diagnostic of an EP. The tubal ring is associated with an ectopic pregnancy in 95 % of cases. Any complex or solid adnexal mass that is not intraovarian is associated with an ectopic pregnancy in 92 % of cases (Table 16.3). Such adnexal findings are present in almost 95 % of EP with each finding being visualized in 7.4 %, 8.3 %, 24.7 %, and 54.1 % (respectively) of EP [17].

Adnexal finding on TVS | Likelihood of ectopic (%) [16] | Frequency of findings [17] |

|---|---|---|

Extrauterine embryo with cardiac activity | 100 | 7.4 |

Adnexal mass with yolk sac without embryonic cardiac activity | 100 | 8.3 |

Adnexal mass with central anechoic area and hyperechoic rim (“tubal ring”) | 95 | 24.7 |

Any complex or solid adnexal mass other than a simple cyst or intraovarian lesion | 92 | 54.1 |

Work-Up for Ectopic Pregnancy

This chapter reviews the hCG and ultrasound findings in ectopic pregnancy. The order in which one performs various tests, including serum progesterone, in patients with suspected EP was evaluated by Garcia and Barnhart in a 2001 paper [18]. The order of these tests included the following:

Ultrasound followed by quantitative hCG if the ultrasound findings were inconclusive

Quantitative hCG followed by ultrasound, when the hCG was >threshold value

Progesterone followed by ultrasound and, if inconclusive, then quantitative hCG

Progesterone followed by quantitative hCG and, when >threshold value, then ultrasound

Ultrasound followed by repeat ultrasound

Clinical examination only

They applied these algorithms to a theoretical cohort of 10,000 patients determining the number of ultrasounds, blood draws, dilatation and curettages, and laparoscopies performed. They then predicted the costs of the various strategies, and their effectiveness in diagnosing Eps. (Table 16.4). Ultimately they recommended either of the first two strategies, as the progesterone methods missed more ectopic pregnancies, the ultrasound only strategy was too costly, and the clinical exam only method to ineffective. Of note, although serum progesterone may be helpful in predicting viability of a pregnancy [19], the Garcia study confirmed the findings of others that progesterone lacks adequate sensitivity in distinguishing ectopic and intrauterine pregnancies [20–22].

Strategy | Days to Dx | Blood draws/10,000 | Total charge per patient | Missed EP per 10,000 | Interrupted IUP per 10,000 |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

Ultrasound → hCG | 1.46 | 5227 | $1958 | 0 | 70 |

hCG → Ultrasound | 1.66 | 14,375 | $1842 | 0 | 122 |

P → Ultrasound → hCG | 1.25 | 12,108 | $1692 | 24 | 25 |

P → hCG → Ultrasound | 1.26 | 15,003 | $1569 | 24 | 39 |

Ultrasound → Ultrasound | 1.21 | 0 | $2486 | 0 | 121 |

Clinical exam only | 1.0 | 0 | $0 | 940 | 0 |

An Argument for Ultrasound First, Tubal Rupture Below the Threshold Level

The Connolly study previously discussed determined the threshold level of hCG should be lowered to 390 mIU/mL [11]. Prior to this study, many practitioners deferred ultrasound until the hCG level was ≥ 1000 mIU/mL. However, an early study by Saxon et al. demonstrated that 50 % of ruptured EPs had a hCG ≤ 999 mIU/mL [23]. This finding was confirmed by the 2014 report of Frates et al. also demonstrating that half of ruptured EPs had a hCG < 1000 mIU/mL. Thus, in patients with suspected EP, with bleeding, pain, and a positive qualitative pregnancy test, performing ultrasound first has value in identifying a definite IUP, EP, or a significant hemoperitoneum (Fig. 16.10). Not visualizing a significant hemoperitoneum allows a more conservative evaluation of such patients, while assuring patient safety.