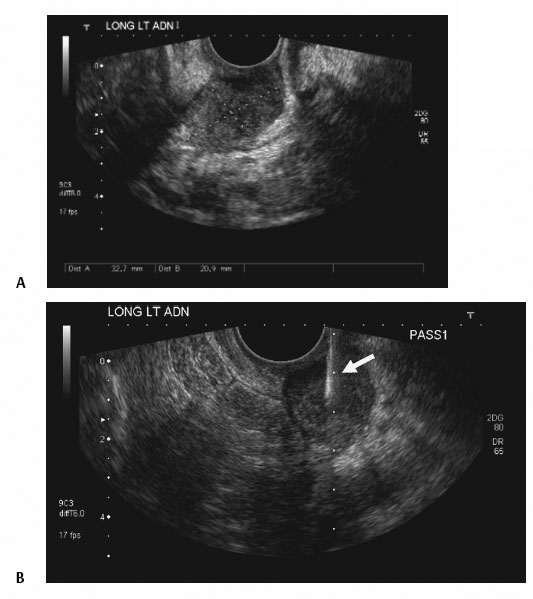

8 Endovaginal Procedures Endovaginal ultrasound-guided interventional procedures are an important tool for the interventionist. These procedures are typically well tolerated by women and can be performed with local anesthesia or no anesthesia at all. Lesions located within the central pelvis, which can be difficult to access by the usual percutaneous transabdominal or transsciatic methods, can often be easily and safely accessed with the endovaginal technique. Real-time needle visualization and no ionizing radiation are additional benefits of endovaginal ultrasound guidance. Positioning is particularly important if the target is located in the anterior aspect of the pelvis. To direct the probe tip toward the anterior pelvis, the probe handle must be moved posteriorly. Raising the patient’s hips with the folded sheets makes it easier to move the probe handle posteriorly. Otherwise, the cart or table that the patient is lying on will prohibit the interventionist from moving the probe handle posteriorly. Fig. 8.1 Hysterosalpingogram tray. The contents include a syringe and connecting tubing (which should be filled with ∼ 15 cc of povidone–iodine solution), a plastic speculum, a long cotton swab, and sponge swabs to clean the perineum. The sponge swabs should be soaked in the povidone–iodine solution and then used to clean the perineum. It can be difficult to have subsequent needle passes enter the vaginal wall at the same site; therefore, it is important to use other landmarks in the pelvis (i.e., vessels, the bladder wall) to help ensure needle penetration at or near the lidocaine wheal. A fine-needle aspiration (FNA) also allows one to assess the vascularity of a lesion directly. With most FNAs, only a few drops of blood or no blood at all may come out while the needle is within the lesion. If several milliliters or more of blood are aspirated during the performance of the FNA, then this suggests that the lesion is quite vascular. For such vascular lesions, it may be prudent to defer performing a cutting needle biopsy to avoid a potential bleeding complication. Alternatively, if a cutting needle is needed, one could perform a core needle biopsy, but with a small needle, such as a 20-gauge cutting needle or smaller. Fig. 8.2 Left adnexal mass in a patient with endometrial carcinoma status post total abdominal hysterectomy/bilateral salpingo-oophorectomy. (A) Image from the endovaginal ultrasound demonstrates the adnexal mass. (B) Endovaginal ultrasound-guided fine-needle aspiration with a 20-gauge Chiba needle (arrow). The biopsy proved an endometrial carcinoma recurrence.

Classification

Endovaginal Ultrasound-Guided Interventional Procedures

Indications

Contraindications

Absolute Contraindication

Relative Contraindication

Patient Preparation

Patient Positioning

Endovaginal Ultrasound-Guided Biopsy

Preprocedural Evaluation and Preparation of the Patient

Equipment

Fine-Needle Aspiration or Cutting Needle Biopsy

Endovaginal Ultrasound-Guided Biopsy for Adnexal/Pelvic Masses and Endometrium

Endovaginal Ultrasound-Guided Biopsies of the Adnexa, Iliac Nodes, or Vaginal Cuff

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree