Long Chen • Ali Akber Hazari • Laura MacNeil • Kieran Murphy

Epistaxis, commonly known as a nosebleed, is the most common otolaryngologic emergency.1 It is estimated that 60% of people have experienced at least one episode of epistaxis, with 6% requiring medical attention.2 Although this medical condition is not always recognized as life-threatening, there have been incidences where epistaxis has led to serious complications, and if not treated effectively, it can be fatal. Therefore, it is crucial that the techniques and treatments used in prevention are well understood.

Many studies indicate that the severity of the epistaxis depends on where the bleed originates. Clinically, anterior bleeds are usually less severe than posterior bleeds, and in about 80% of cases, epistaxis originates from the anterior septal area.1,3 Kiesselbach plexus, an “anastomosis with branches from both the internal and external carotid artery systems,” is responsible for most anterior septal nosebleeds, for example, those which children experience in the winter time.3 Anterior septal nosebleeds would also include epistaxis resulting from trauma, digital irritation, and dryness.3 The posterior septal area is where epistaxis can be severe, more specifically the Woodruff area where the “anastomoses of the sphenopalatine and pharyngeal arteries is found.”3

In a case of epistaxis, the aim of treatment is to do at least one of the following: reduce bleeding through decreasing arterial inflow pressure, reduce mucosal irritation, or reduce blood flow by inducing clot formation. The initial treatment of epistaxis is based on nasal packing and chemical or electrocautery.4 This is usually successful for the anterior septal area and is also a first-line therapy for posterior epistaxis.4,5 However, the posterior nasal vault is located in an inaccessible region, causing this method to prove ineffective 25% to 50% of times.6,7 Nasal packing can also be painful for the patient.6 Patients with preexisting pulmonary or cardiac problems are at serious risk for hypoxia, cardiac arrhythmias, or sepsis when treated with nasal packing.8 This is a particular risk in patients with heart disease where the mucosal absorption of epinephrine can result in ischemia.

If the prior proves unsuccessful, patients are treated with nasal packing along with transantral maxillary artery and ethmoid artery ligation.8 The aim of this treatment is to surgically achieve homeostasis at the affected area by decreasing arterial blood flow so epithelial repair and clotting may occur.8 However, this procedure is not always successful in achieving the desired homeostatic result and also puts the patient at risk for anesthetic problems, septal perforation, infraorbital nerve dysfunction, ophthalmoplegia, blindness, or myocardial infarction.8 Rarely, postsurgical pseudoaneurysms develop.

Therefore, both these methods have been proven to carry a relatively high number of risks and possible complications, making alternative therapies more favorable for patients with severe cases of epistaxis.

One such alternative therapy, which has proven to be very effective, is endovascular embolization. Embolization is the process of inducing blood clots or embolus to occlude blood flow. In 1974, Sokoloff et al.9 reported the first successful percutaneous embolization of the internal maxillary artery causing nasal hemorrhage. A later study conducted in 1995 by Elahi et al.7 demonstrated a 96% success rate in treating patients with intractable epistaxis using embolization. Embolization is a relatively short procedure, which increases both safety and accuracy.7 Moreover, a patient who has undergone embolization is able to remove his or her posterior nasal pack earlier, which allows for a reduced hospital stay and increased patient comfort.7 The technique has since then been widely accepted and its efficacy confirmed.10 Nevertheless, in some institutions and in case the of conservative treatment failure, angiographic embolization remains the procedure of first choice.11

DEVICE/MATERIAL DESCRIPTION

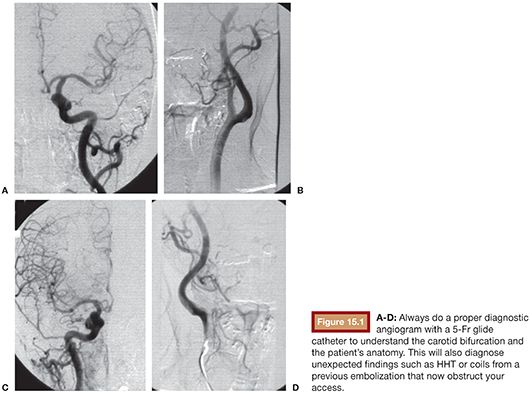

Once a year, our group is asked to review strokes that occur during epistaxis embolizations. Usually, this happens in a procedure performed by a well-intentioned interventional radiologist who uses a 5-Fr glide catheter to close the internal maxillary. This is a recipe for disaster. Strict guiding catheter and microcatheter technique must be used. Embolization is a procedure that can be conducted using various techniques or materials, for example, microcoils, gelfoam, glue, and polyvinyl alcohol (PVA) foam. Microcoils are overused by inexperienced practitioners and are a major problem in patients with recurrent bleeding as they recanalize, allowing reperfusion but obstructing embolization access. In transarterial embolization, physicians will use 6-Fr guiding catheters, microcatheters, and microwires to access the sphenopalatine branch of the internal maxillary artery.12 As it is difficult to reach areas in the nasal cavity, microcatheters are often preshaped in a 30- to 45-degree angle.12 The materials mentioned earlier are sometimes used in combination with one another. Patients should be heparinized during procedures to decrease the risk of periprocedural stroke.

PVA particles with a diameter of 300 to 500 μm are used for embolization of epistaxis.13 Particles with a smaller diameter should be avoided as they can navigate through the skull base extracranial–intracranial dangerous anastomosis and cause stroke. On the other hand, a larger diameter can clump and block the microcatheter. To balance the benefit of embolization therapy and the risk of complications, it is recommended that the range in diameter is between 300 and 500 μm.4,14

N-butyl cyanoacrylate (NBCA), detachable balloons, and microcoil embolization should be reserved for massive bleeding, when it is necessary to sacrifice internal carotid artery for epistaxis caused by internal carotid artery lesion such as a gunshot wound.15 For arteriovenous malformation (AVM) or dural arteriovenous fistula (DAVF), NBCA or Onyx (Covidien, Irvine, California) can be employed for embolization.16–18

TECHNIQUE

Transarterial embolization therapy should be conducted under conscious sedation, but in an agitated patient, general anesthesia (GA) should be used.19,20 Embolization under GA is recommended for patients with major blood loss, especially for cases of epistaxis caused by trauma, which are usually accompanied with a major blood loss and of higher risk for aspiration. Confused patients move and you lose your road map guidance. In that situation, it is harder to detect excessive reflux of embolic material retrograde from the catheter tip and potentially into the carotid bifurcation and hence internal carotid artery and cause stroke.

Complete common carotid and bilateral internal and external carotid arterial angiography should be conducted before embolization19,21 (Fig. 15.1). Preembolization angiography should be performed to indentify lesions such as AVMs, DAVF, and pseudoaneurysms. Preembolization diagnostic angiography can identify if extracranial–intracranial dangerous anastomosis exist. The key dangerous anastomosis exists between the middle meningeal artery and the ophthalmic artery. Due to anatomical variation, dangerous anastomoses exist between external and internal carotid arteries and their ophthalmic artery branches. Even if there is no extracranial–intracranial dangerous anastomosis detected by conventional angiography, potentially dangerous anastomosis will still open with an increase in the injection pressure during the embolization process. Internal and external carotid artery anastomoses can occur with vidian artery, artery of the foramen rotundum, the ascending pharyngeal artery, branches of middle meningeal artery and accessory meningeal artery, sphenopalatine artery, and branches between sphenopalatine artery and ophthalmic artery (Fig. 15.2).4,19 If embolic materials traverse through these anastomosis from external carotid artery to internal carotid artery or ophthalmic artery, it may cause cranial nerve palsy, loss of vision from retinal artery embolization, or even stroke.19,22

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree