12.3 Unmedicated Schizophrenic Patients

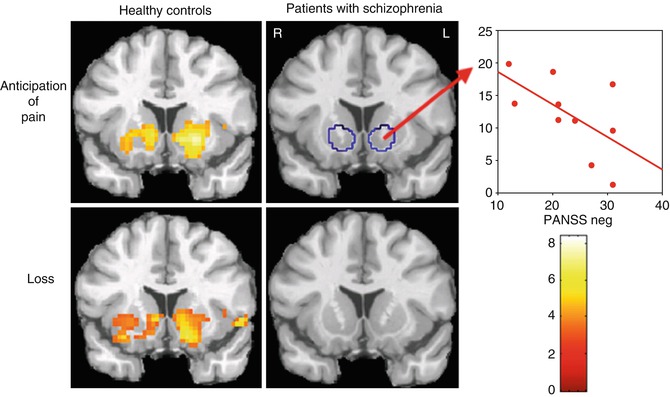

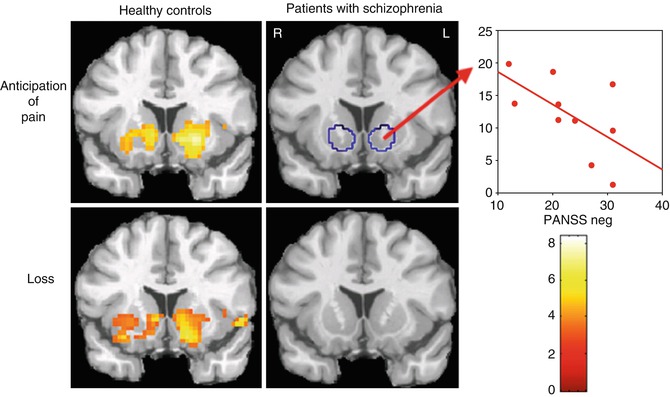

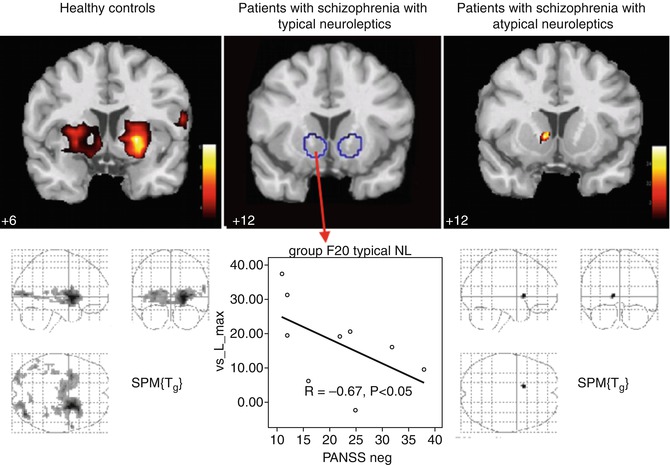

In a first study (Juckel et al. 2006a), ten unmedicated schizophrenic patients (ages, 26.8 ± 7.8 years) and ten healthy controls (ages, 31.7 ± 8.4 years) were examined. Both groups were matched according to gender, age, left or right handed, as well as task performance concerning the monetary game. Of the schizophrenic patients, seven have never been treated with neuroleptics and three had taken neuroleptics 2 years ago. There was no difference between both groups concerning total monetary gain or the reaction times. In accordance with the findings of Knutson et al. (2001), healthy controls showed a BOLD response at both sides of the ventral striatum during the anticipation of monetary gain versus the neutral condition (contrast “anticipation of monetary gain > neutral condition” in healthy control subjects at the left side ((x y z) = (−21 6 −3), t = 5.63) and at the right side ((x y z) = (9 6 −5), t = 4.26)). In contrast, untreated schizophrenic patients displayed no significant activation in the ventral striatum, though the achievements did not show any differences for both groups (Fig. 12.2). In comparing both groups a significant higher activation was observed in the left ventral striatum in healthy controls compared to the schizophrenic patients concerning the anticipation of monetary gain ((x y z) = (−15 9 −3), t = 3.29) and loss ((x y z) = (−18 6 −5), t = 3.24) compared with the neutral conditions. Within the group of schizophrenic patients, the BOLD response correlated in the left ventral striatum inversely with the severity of the negative symptomatology (measured with the PANSS negative score; Spearman’s R = −0.66, P < 0.05), i.e., a reduced activity of the ventral striatum concerning reward-indicating stimuli was correlated with a higher negative symptomatology.

Fig. 12.2

Unmedicated patients with schizophrenia and healthy controls as well as the relationship to negative symptoms

In a recently published study (Juckel et al 2012), it could be shown that in ultra high-risk persons (prodromal schizophrenia) (mean age, 25.5 ± 4.6 years), matched with healthy controls in regard of age, gender, and test performance, the activity of the ventral striatum in prodromal patients during the Knutson paradigm is approximately positioned in the center compared to completely manifested schizophrenic patients on the one side and healthy probands on the other side. A remaining activation concerning monetary anticipation, but also concerning avoidance of loss, was significantly different concerning the left and right striatum compared with healthy persons (Juckel et al. 2012).

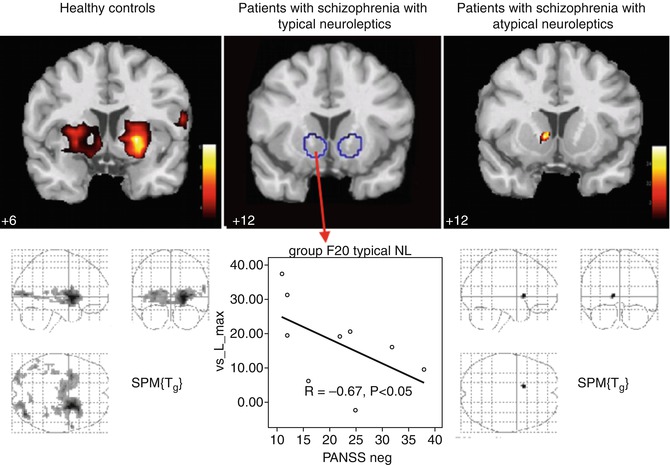

12.4 Typical Versus Atypical Neuroleptics: A Cross-Sectional Study

In a further study (Juckel et al. 2006b) the influence of typical and atypical neuroleptics concerning the reward system in schizophrenic patients was examined. Three groups were tested: one group of ten schizophrenic patients, which received typical neuroleptics (four flupenthixol 12 ± 4 mg, four haloperidol 10 ± 5 mg, and two fluphenazine 12 ± 4 mg); one group of schizophrenic patients, which were treated with atypical neuroleptics (four with risperidone 5 ± 1 mg, four with olanzapine 19 ± 6 mg, one with aripiprazole 30 mg, and one with amisulpride 300 mg); and a healthy control group. There were no significant differences found between the three groups concerning age, gender, and total gain. There were no significant differences concerning the psychopathology of both patient groups (PANSS total in patients under typical neuroleptics, 70.11 ± 20.37, and those under atypical neuroleptics, 64.44 ± 22.59). The healthy control subjects showed again an activation concerning the contrast between gain anticipation versus neutral condition at both sides of the ventral striatum (left, (x y z) = (−21 5 −3), t = 9.53, and right, (x y z) = (12 2 −10), t = 4.25). In schizophrenic patients under typical neuroleptics, no activation of reward-indicating stimuli was observed, whereas in schizophrenic patients with atypical neuroleptic medication, an activation of the right ventral striatum was observed ((x y z) = (12 12 −1), t = 3.58) (Fig. 12.3). In comparing the groups, a significant difference between the healthy subjects and the schizophrenic patients under typical neuroleptics ((x y z) = (−21 9 −3), t = 3.39) was observed, but there was no difference between healthy controls and patients under atypical neuroleptics. Within the group of persons being treated with typical neuroleptics – as well as unmedicated schizophrenic patients – an inverse correlation between reduced activation concerning reward-indicating stimuli and the severity of the negative symptomatology was observed (Spearman’s R = −0.67, P < 0.05).

Fig. 12.3

Effects of typical versus atypical neuroleptics on the ventral striatum in patients with schizophrenia (cross-sectional study)

12.5 Switch From Typical to Atypical Neuroleptics: Reactivation of the Ventral Striatum in Schizophrenic Patients

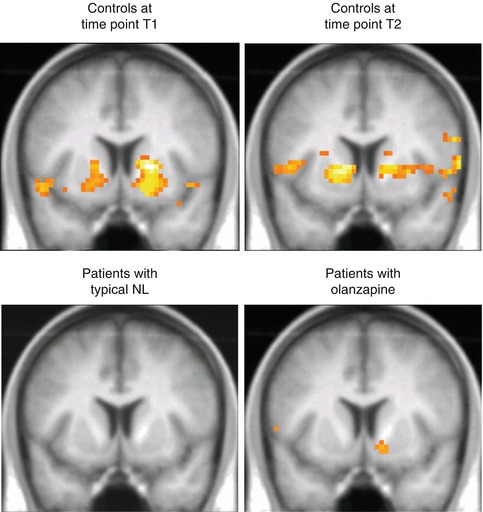

As cross-sectional studies are not sufficiently valid in order to evaluate effects of antipsychotic medication on ventral striatum activation within the MID task, further studies have been carried out by treating schizophrenic patients with a typical neuroleptic agent (haloperidol or flupenthixol) for at least 2 weeks and afterwards with an atypical neuroleptic medication (risperidone, olanzapine, or aripiprazole) for another 2 weeks. After the respective treatment for 2 weeks, the patients were examined by fMRI and the “monetary incentive delay task” and compared with healthy controls, who were examined twice by fMRI, too, after similar time intervals. Concerning changes to olanzapine (Schlagenhauf et al. 2008), ten schizophrenic patients were first examined by fMRI under typical neuroleptics (haloperidol, 10.8 ± 4.3 mg/day; flupenthixol, 7.0 ± 5.1 mg/day) and were afterwards treated with olanzapine (18.3 ± 7.5 mg/day). The patients were treated with typical neuroleptics for 17.8 ± 15.0 days and with olanzapine for 18.5 ± 7.5 days. The repeated examination by fMRI under olanzapine was carried out after 31.7 ± 17.3 days after the first examination under typical neuroleptics. Ten healthy subjects were also examined twice after a period of 32.7 ± 15.5 days in order to control a potential time effect. In anticipation of a monetary gain, healthy volunteers showed a significant activation of the ventral striatum (left, (x y z) = (−19 6 −9), t = 3.87, and right, (x y z) = (18 6 −3), t = 4.7), whereas the schizophrenic patients did not show any activity under the typical neuroleptics (Fig. 12.4). However, under the treatment of olanzapine, an activation of the ventral striatum could be observed on the right side ((x y z) = (15 6 −12), t = 4.36) in schizophrenic patients. In the healthy control subjects, activation of the ventral striatum due to anticipation of reward remains quite stable over time. Presumably due to the secondary negative symptomatology, in the patients, there was an observed significant correlation between the activation of the ventral striatum and the PANSS negative score (r =−0.721, P = 0.019) only under treatment with typical neuroleptics in patients.

Fig. 12.4

Activation of the ventral striatum under several weeks of treatment with an atypical neuroleptic agent (olanzapine) after switching from a classical typical neuroleptic (mostly haloperidol, flupenthixol) in patients with schizophrenia in comparison to healthy subjects with two recordings in similar time interval distance

In a further study (Juckel, Schlagenhauf et al.; not published yet) in eight patients suffering from schizophrenia, who received a typical medication with haloperidol or flupenthixol, the medication was changed to risperidone. The age average of these male patients was 35 ± 13 years versus the examinations of 33.6 ± 12.5 years. The test performance did not show any differences for both groups. In the course of this study, the patients were tested again after a period of nearly 2 months in order to minimize effects of classical neuroleptics, e.g., haloperidol and flupenthixol, which are acting a long time. With T1 under a classical neuroleptic, schizophrenic patients showed a significantly lower activation compared to healthy controls (t-values 2.5–3.0, t = 0.03–0.04, corrected for ventral striatum ROI FDR). After changing the medication to risperidone, the MID paradigm showed a visible increase of the activity in the ventral striatum concerning the gain anticipation compared with healthy subjects at the left side (t = 3.6, P = 0.04 corrected for ROI) as well as at the right side (t = 3.6, P = 0.02 corrected for ROI), which substantiates a regeneration of the dopaminergic reward system in the ventral striatum after change over to an atypical neuroleptic. The difference between the administration of risperidone compared to a typical neuroleptic in schizophrenic persons was not significant due to the small number of cases; in the ventral striatum a t-value of 2.1 and a p-value of 0.186 were ascertained. A change from typical neuroleptics to aripiprazole (Schlagenhauf et al. 2010) also resulted in an increased activation under aripiprazole compared to typical medication in the ventral striatum t = 2.17, P < 0.05.

12.6 Discussion

For the first time, we could substantiate a dysfunction of the reward system in patients with schizophrenia. They showed a reduced activation of the ventral striatum, a core region of the reward system, compared to healthy controls, and the severity of the negative symptomatology was associated with the reduced activation in the ventral striatum. The reduced ventral striatal activation in schizophrenic patients could be potentially an explanation for an increased dopaminergic “noise” in this region interfering with the processing of cue-elicited signals. In unmedicated schizophrenic patients, an increased dopaminergic transmission in the ventral striatum was observed again (Abi-Dargham et al. 2000). This interpretation is substantiated by a study of Knutson et al. (2004

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree