Fig. 8.1

Plain chest film a shows a central venous catheter positioned in the superior vena cava (arrow). MDCT sagittal reformatted image b shows a large infectious thrombus (arrow) mixed to air bubble (arrowhead) in the superior vena cava lumen, closed to the catheter

Catheter-related thrombosis can be intraluminal or periluminal. Several factors influence the formation of catheter-related venous thrombosis including catheter duration, the caliber of the catheter, the access vein used, or systemic comorbidities [14]. Although most thrombosis is either asymptomatic or results in catheter blockage alone, serious life-threatening vascular events, including SVC syndrome and pulmonary embolism may occur.

The common sources of intravascular foreign body (Fig. 8.2) are lost guidewires during insertion and catheter fractures related to tearing of the catheter during insertion or following catheter damage during removal or traction on the catheter-hub junction. Fracture of CVCs is a rare but serious complication of their use.

Fig. 8.2

MDCT coronal reformatted image a shows a long venous catheter fragment at the left paravertebral side. MDCT sagittal reformatted image b reveals the presence of a large infectious venous catheter fragment surrounded by air bubbles (arrows) in the lumen of an anomalous left course vena cava

8.3 Metallic Stents

Endoprosthetic stents composed of metals and other materials were originally designed for intravascular use, but they have found extensive application in many other situations [15–17]. With respect to the vascular tree, they are used to maintain or restore the patency in compromised arterial and venous lumens. Angioplasty and stenting of femoral, iliac, renal, and coronary arterial lesions are common, and endovascular stents are being applied to the treatment of aortic aneurysms.

Well-known complications of these stents include intimal dissection, thrombosis, malpositioning, infections, and rupture (Fig. 8.3).

Fig. 8.3

MDCT –VR reformatted image demonstrates a left iliac stent rupture (arrow)

8.4 Endovascular Abdominal Aortic Aneurysm Repair

Endovascular repair of an abdominal aortic aneurysm (EVAR) was first performed by Dr Juan Parodi in Argentina in 1991 [18]. It has since gained increasing acceptance over open repair due to its low invasiveness and feasibility for high-risk patients.

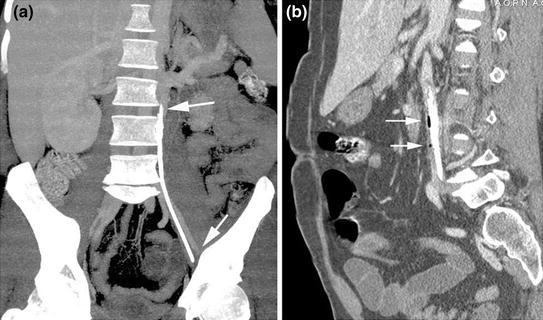

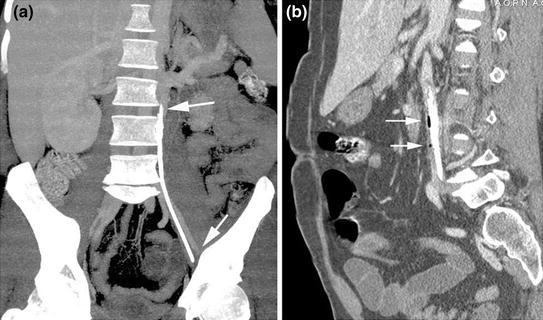

Imaging surveillance post-EVAR is accepted as mandatory to identify several complications: stent or hook fractures (Fig. 8.4), endoleaks (Fig. 8.4), separation of modular components, aneurysm enlargement, and distal migration of the endograft [19]. Moreover, any implanted device may become infected, and there are uncommon cases of infection of stent-grafts (Fig. 8.5). The appearances are similar to infected surgical grafts with retroperitoneal inflammatory change, gas in the sac, and periaortic fluid collections.

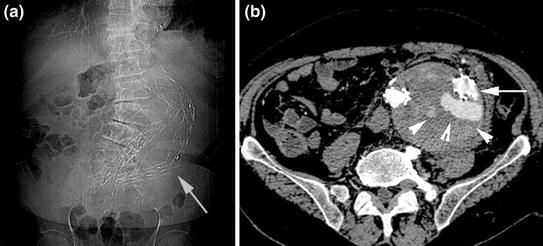

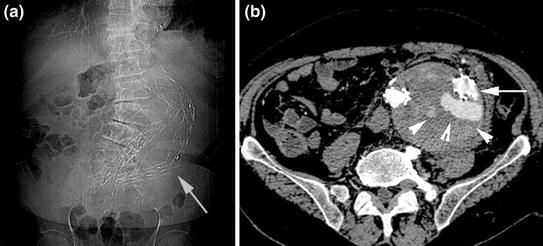

Fig. 8.4

Plain abdominal film a performed in patient post-EVAR shows an alteration of device configuration with left iliac branch rupture (white arrow). MDCT axial image b confirms the stent wire fracture (arrow), associated with contrast medium extravasation inside the native aortic aneurysm lumen (arrowheads)

Fig. 8.5

MDCT coronal reformatted image shows the infection of the aortobisiliac endoprosthesis with thrombotic lumen mixed to air bubbles (arrows)

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree