Fig. 16.1

Barium swallow shows normal indentations of the esophagus caused by the aortic arch, left main bronchus, and left atrium (all annotated)

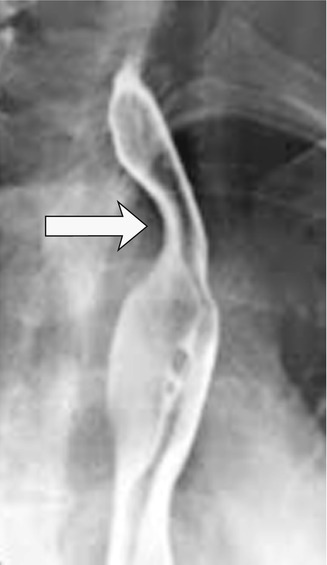

Fig. 16.2

Thirty-two-year-old woman who presented with dysphagia. Barium swallow shows posterior indentation of the esophagus (arrow) caused by an aberrant left subclavian artery in a patient with a right-sided aortic arch

16.2.2 Eosinophilic Esophagitis

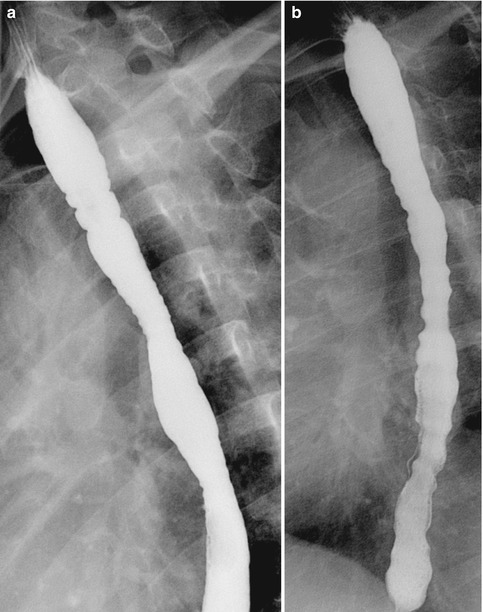

Eosinophilic esophagitis is an immune-mediated hypersensitivity reaction to inhaled or ingested allergens which affects genetically susceptible individuals. The condition more commonly occurs in the third or fourth decade of life, with a male predominance (male to female ratio 3:1). The incidence is approximately 6 in 10,000 population. Patients usually present with difficulty in swallowing solids and with food impaction. Management options include dietary modification, medical therapy, or surgical dilatation for symptomatic strictures. Typical appearances on barium swallow which are highly specific for eosinophilic esophagitis consist of multiple persistent rings in the mid- and/or distal esophagus (Shanbhogue et al. 2010) (Fig. 16.3a). Compare this with tertiary contractions, which are temporary and a more common finding (Fig. 16.3b).

Fig. 16.3

(a) Barium swallow in a young man with dysphagia shows ring-like constrictions within the upper and mid-esophagus, typical of eosinophilic esophagitis. These rings persisted throughout the investigation. (b) Compare this with another patient with temporary tertiary contractions of the esophagus

Learning Points

As well as assessing the mucosa on a barium swallow, look at the morphology of the tract.

Look for extrinsic compressions and indentations that do not follow normal anatomy and assess whether they are temporary or permanent.

16.3 Gastric Carcinoma on CT

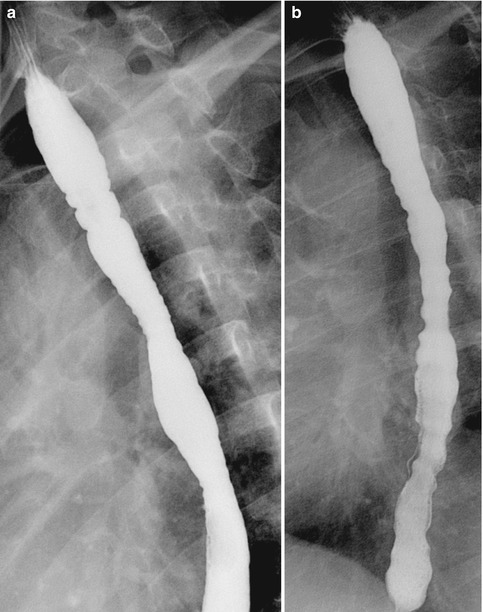

Gastric cancer is the fifth most common cause of cancer-related death worldwide. It is often diagnosed late and has a poor prognosis, with an overall 5-year survival rate of less than 20 % in the UK. Multi-detector CT (MDCT) is used to stage gastric carcinoma preoperatively. Imaging features of the stomach on MDCT can be misleading, especially if not protocolled specifically to assess for gastric carcinoma. Prone imaging and gas-forming granules to distend the stomach, as well as intravenous contrast administration, can increase the sensitivity and specificity of detecting pathological gastric wall thickening (Fig. 16.4a, b). The use of negative oral contrast may also be useful in increasing the conspicuity of subtle pathological gastric wall enhancement (Hargunania et al. 2009). Following esophageal surgery for esophageal carcinoma, imaging for recurrence can be particularly challenging, especially with abnormal anatomy (gastric pull-through). Patients often present with vague chest or upper abdominal symptoms. The search for ancillary signs, such as nodal enlargement and pathological soft-tissue enhancement, is often useful in diagnosing disease recurrence (Upponi et al. 2007) (Fig. 16.5).

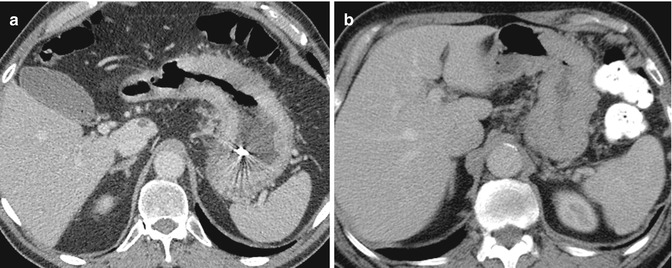

Fig. 16.4

(a) Sixty-four-year-old man who presented with anemia and epigastric discomfort. Axial CT image of the upper abdomen shows diffuse gastric wall thickening due to carcinoma. Nasogastric tube produces streak artifacts within the stomach. (b) Axial CT image of the upper abdomen in another patient shows apparent gastric wall thickening, which was found to be normal on endoscopy. Note that the stomach is not distended and the serosa is normal

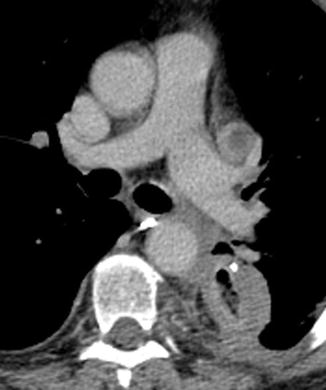

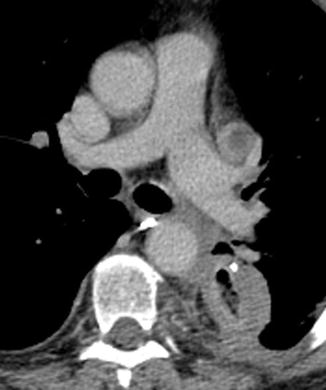

Fig. 16.5

Seventy-eight-year-old man with back pain, presenting 8 months following esophagectomy for carcinoma. Axial CT image of the mid-thorax shows diffuse thickening of the wall of the gastric pull-through. There is a nasogastric tube in situ. Note the adjacent posterior enhancing pleural thickening, consistent with tumor invasion. There is also a necrotic mediastinal node anterior to the left main pulmonary artery. The patient had esophageal carcinoma recurrence in the gastric pull-through

Learning Points

The gastric wall is difficult to assess on CT.

Look for ancillary signs such as lymphadenopathy, soft-tissue enhancement, and serosal irregularity.

If specifically asked to exclude gastroesophageal carcinoma, protocol scans appropriately to obtain adequate distension.

16.4 Bowel Wall Erosion

16.4.1 Gastric Band Slippage

The rise in the prevalence of obesity in developed countries has caused an increase in bariatric surgery as a management option. Gastric banding is a common procedure carried out for morbid obesity and has a high complication rate of up to 40 %. It is therefore important to know the normal imaging findings of gastric bands and to recognize the imaging features of complications. The procedure involves insertion of a non-distensible ring around the proximal stomach, creating a small proximal gastric “pouch,” the distension of which produces satiety early during oral intake. Gastric band erosion and slippage are common complications of bariatric surgery, with patients often presenting with upper abdominal pain. CT may show intramural gas in early erosion or complete erosion of the band into the gastric lumen (Quigley et al. 2011) (Fig. 16.6).

Fig. 16.6

Twenty-eight-year-old woman who had previous gastric banding now presenting with epigastric pain. Axial CT of the upper abdomen shows that the gastric band is still outside the stomach (short arrow) but with adjacent gastric wall edema. Part of the band has eroded into the gastric lumen (long arrow)

16.4.2 Aortoduodenal Fistula

A mycotic aneurysm that arises at the level of the duodenum may erode through the duodenal wall, resulting in a fatal aortoduodenal fistula. The inflammatory tissue surrounding a mycotic aneurysm should be carefully inspected to detect any evidence of fistulation into adjacent structures. If a fistula is present, gas locules may be seen within the aorta. In the illustrated case, a CT colonography was performed as a non-enhanced scan to look for a cause of anemia and change in bowel habit. The initial CT showed a cuff of inflammatory tissue around the aorta at the level of the duodenum, which had an unusual outpouching (Fig. 16.7a). This was not seen on the initial scan. A few months later, a further CT scan was performed following increasing abdominal symptoms. The penetrating ulcer was now seen more clearly, and there was an aortoduodenal fistula with gas locules within the aorta (Fig. 16.7b, c).

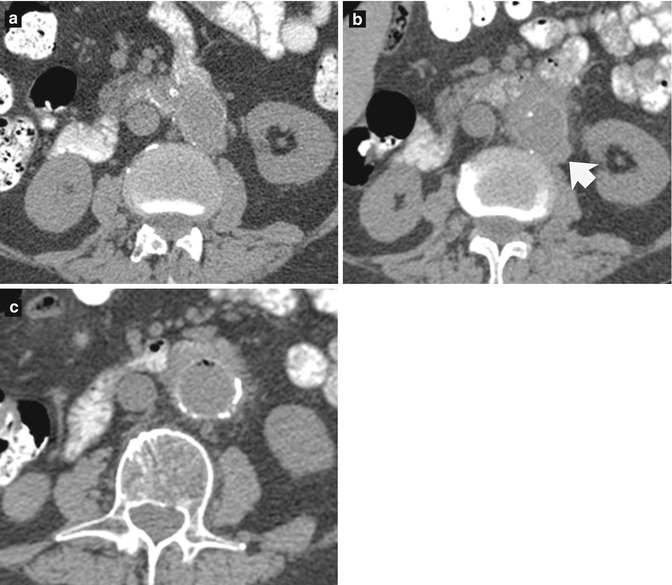

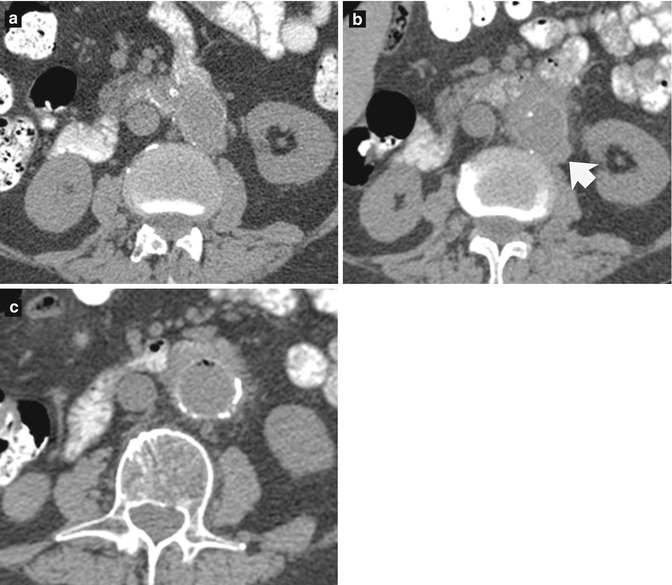

Fig. 16.7

Sixty-nine-year-old man who presented with anemia and change in bowel habit. (a) Axial CT image, taken at the level of the kidneys, shows adherence of the third and fourth parts of the duodenum to the aorta. (b) Repeat axial CT image was taken a few months later when the patient had developed melena. There is now diffuse thickening of the aortic wall and inflammatory stranding of the surrounding fat. There is a penetrating ulcer at the posterolateral aspect of the aorta which is now seen more clearly (arrow). (c) Just inferiorly, gas locules are present within the aortic lumen

Learning Points

Remember the normal postoperative appearances of gastric bands, band slippages, and erosions.

Always remember to look carefully at all imaged structures on CT.

Look for inflammatory stranding of fat, an ancillary sign which can lead you to an area of abnormality.

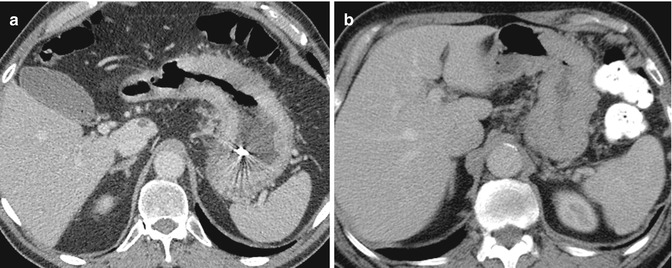

16.5 Duodenal Malrotation and Normal Variations in Pancreatic Contour

Intestinal malrotation is a congenital abnormality, which can result in midgut volvulus. Neonates usually present in the first week of life with proximal small bowel obstruction and bilious vomiting. Approximately 25 % of cases are asymptomatic and are found incidentally in adult life. Malrotation has been associated with variations in pancreatic head contour. A bulky pancreatic head can be mistaken for pancreatic tumor, but in malrotation, the bulky pancreatic tissue is of the same attenuation and of the same enhancement pattern as normal pancreas (Chandra et al. 2012) (Fig. 16.8).

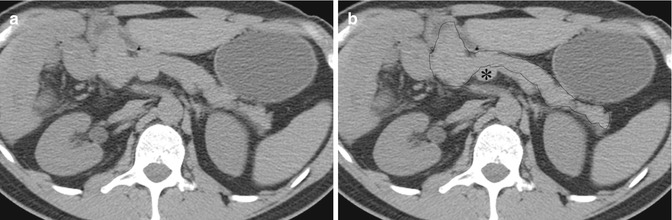

Fig. 16.8

Twenty-five-year-old man who presented with right loin to groin pain (a) Non-enhanced axial CT image of the abdomen shows a mixed elongated and globular-shaped pancreatic head. (b) Annotated image illustrates that the duodenum does not pass posterior to the pancreas (outlined), and the superior mesenteric artery lies lateral to the superior mesenteric vein (asterisk), in keeping with malrotation

Learning Point

An abnormal contour of the pancreas may be associated with malrotation.

16.6 Missed Duodenal Pathology in Small Bowel Enema

The small bowel enema requires insertion of a nasojejunal (NJ) tube before controlled administration of contrast agent via the NJ tube to delineate the small bowel. It is important to note that the duodenum is not usually opacified and pathology can be missed within this region. In the illustrated case, a small bowel enema study was performed where there was difficulty in NJ tube insertion. Following some contrast administration, there was an evident stricture at the junction of the second and third parts of the duodenum, obstructing the passage of the NJ tube (Fig. 16.9a, b). In this case, the pathology was demonstrated. However, if the stricture was less narrow, the tube may have passed and the contrast material may not have refluxed back far enough to delineate the duodenal tumor. The extent of visualization of the duodenum at gastroscopy is variable, so that the duodenum can be a “blind” area for both the endoscopist and the radiologist. This limitation may still apply with cross-sectional enteroclysis techniques (CT or MR enteroclysis).

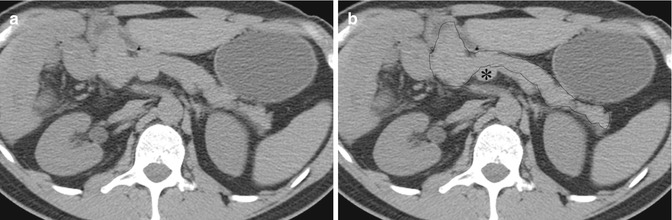

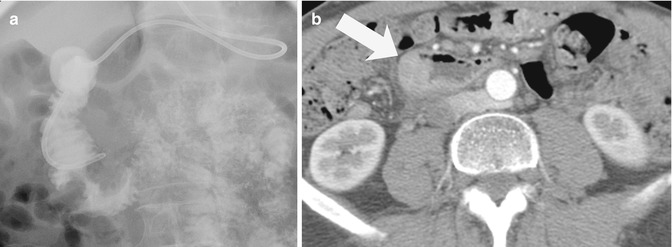

Fig. 16.9

Fifty-four-year-old woman who presented with epigastric pain and bloating. (a) Small bowel barium enema was performed during which there was difficult intubation. The tube did not pass beyond the second part of the duodenum. There was an apple-core stricture at the junction of the second and third parts of the duodenum. (b) Axial CT image taken at the level of both kidneys shows an enhancing soft-tissue tumor in the D2/3 region (arrow) Biopsy confirmed the diagnosis of adenocarcinoma

Learning Point

The duodenum can be a “blind” area on both endoscopy and small bowel enema; therefore pathology may be missed within this region.

16.7 Small Bowel Lymphoma

Lymphoma of the small bowel can present in many morphological forms. Aneurysmal dilatation is quite specific but occurs in a minority of cases. There can be marked thickening of areas of involved bowel wall, with no ulceration and only minor change in caliber of the lumen or distortion of the valvulae conniventes. At barium examinations, therefore, the abnormalities can be very subtle (Fig. 16.10a). On CT, the abnormality is much more conspicuous with gross focal bowel wall thickening (Ghai et al. 2007) (Fig. 16.10b).

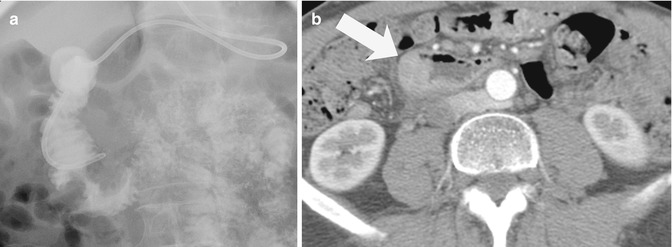

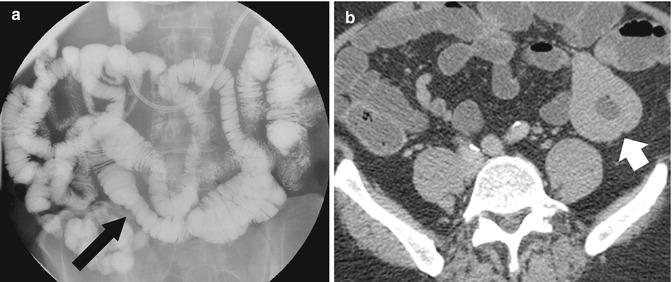

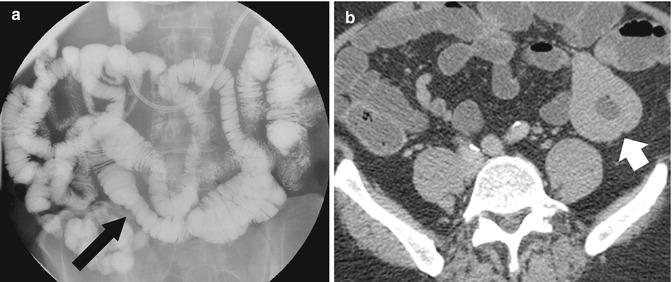

Fig. 16.10

Forty-five-year-old woman who presented with bloating and abdominal discomfort. (a) Small bowel barium enema shows an abnormal loop of the jejunum with thickened folds and minimal luminal narrowing (arrow). This is a subtle abnormality. (b) Axial CT image of the lower abdomen shows gross bowel wall thickening (white arrow), which is much easier to appreciate than on the barium study

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree