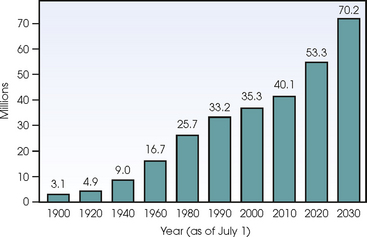

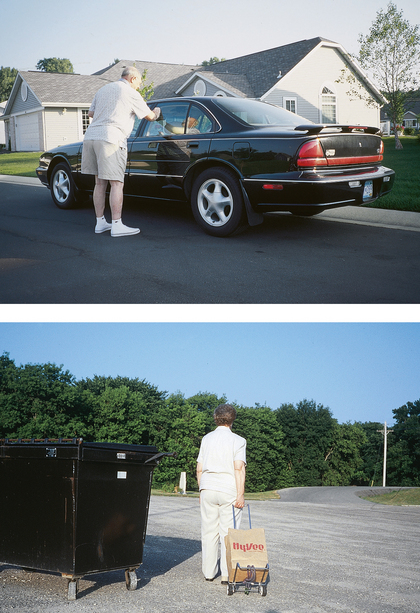

27 The acceleration of the “gray” American population began when individuals born from 1946-1964 (known as the “baby boomers”) began to turn age 50 in 1996. The number in the age 65 and older cohort is expected to reach 70.2 million by 2030 (Fig. 27-1). The U.S. experience regarding the increase in the elderly population is not unique; it is a global one. As of 1990, 28 countries had more than 2 million persons older than 65, and 12 additional countries had more than 5 million people older than 65. The entire elderly population of the world has begun a predicted dramatic increase for the period 1995-2030. The economic status of elderly adults is varied and has an important influence on their health and well-being (Fig. 27-2). Most older people have an adequate income, but many minority patients do not. Single elders are more likely to be below the poverty line. Economic hardships increase for single elders, especially women. Of the population older than age 85, 60% is women, making women twice as likely as men to be poor. By age 75, nearly two thirds of women are widows. Financial security is extremely important to an elderly person. Many elderly people are reluctant to spend money on what others may consider necessary for their wellbeing. A problem facing aging Americans is health care finances. Elderly individuals often base decisions regarding their health care not on their needs but exclusively on the cost of health care services. Aging is a broad concept that includes physical changes in people’s bodies over adult life; psychological changes in their minds and mental capacities; social psychological changes in what they think and believe; and social changes in how they are viewed, what they expect, and what is expected of them. Aging is a constantly evolving concept. Notions that biologic age is more critical than chronologic age when determining health status of the elderly are valid. Aging is an individual and extremely variable process. The functional capacity of major body organs varies with advancing age. As one grows older, environmental and lifestyle factors affect the age-related functional changes in the body organs. Advancements in medical technology have extended the average life expectancy in the United States by nearly 20 years over the past halfcentury, which has allowed senior citizens to be actively involved in every aspect of American society. People are healthier longer today because of advanced technology; the results of health promotion and secondary disease prevention; and lifestyle factors, such as diet, exercise, and smoking cessation, which have been effective in reducing the risk of disease (Fig. 27-3). Most elderly patients seen in the health care setting have been diagnosed with at least one chronic condition. Individuals who in the 1970s would not have survived a debilitating illness such as cancer or a catastrophic health event such as a heart attack can now live for more extended periods, sometimes with various concurrent debilitating conditions. Although age is the most consistent and strongest predictor of risk for cancer and for death from cancer, management of an elderly cancer patient becomes complex because other chronic conditions, such as osteoarthritis, diabetes, chronic obstructive pulmonary disease, and heart disease, must also be considered in their care. Box 27-1 lists the top 10 chronic conditions for people older than 65 years. A 1995 study by Rarey concluded that most of 835 radiographers surveyed in California were not well informed about gerontologic issues and were not prepared to meet the needs of their patients older than age 65.1 Reuters Health reported from a Johns Hopkins study that medical students generally have poor knowledge and understanding of elderly adults, and this translates to an inferior quality of care for older patients. More education in gerontology is necessary for radiographers and physicians. Education would enable health care providers to adapt imaging and therapeutic procedures to accommodate mental, emotional, and physiologic alterations associated with aging and to be sensitive to cultural, economic, and social influences in the provision of care for elderly patients. A positive attitude is an important aspect of aging. Many older people have the same negative stereotypes about aging that young people do.1 For them, feeling “down” and depressed becomes a common consequence of aging. One of five people older than age 65 in a community shows signs of clinical depression. Yet health care professionals know that depression can affect young and old. Research has shown most elderly people rate their health status as good to excellent. How elderly persons perceive their health status depends largely on their successful adaptation to disabilities. The aging process alone does not likely alter the essential core of the human being. Physical illness is not aging, and age-related changes in the body are often modest in magnitude. As one ages, the tendencies to prefer slower-paced activities, take longer to learn new tasks, become more forgetful, and lose portions of sensory processing skills increase slowly but perceptibly. Health care professionals need to be reminded that aging and disease are not synonymous. The more closely a function is tied to physical capabilities, the more likely it is to decline with age, whereas the more a function depends on experience, the more likely it will increase with age. Box 27-2 lists the most common health complaints of elderly adults. An elderly person may show decreases in attention skills during complex tasks. Balance, coordination, strength, and reaction time all decrease with age. Falls associated with balance problems are common in the elderly population, resulting in a need to concentrate on walking. Not overwhelming elderly adults with instructions is helpful. Their hesitation to follow instructions may be a fear instilled from a previous fall. Sight, hearing, taste, and smell all are sensory modalities that decline with age. Older people have more difficulty with bright lights and tuning out background noise. Many elderly people become adept at lip reading to compensate for loss of hearing. For radiographers to assume that all elderly patients are hard of hearing is not unusual; they are not. Talking in a normal tone, while making volume adjustments only if necessary, is a good rule of thumb. Speaking slowly, directly, and distinctly when giving instructions allows older adults an opportunity to sort through directions and improves their ability to follow them with better accuracy (Fig. 27-4). One of the first questions asked of any patient entering a health care facility for emergency service is, “Do you know where you are and what day it is?” Health care providers need to know just how alert the patient is. Although memory does decline with age, this is experienced mostly with short-term memory tasks. Long-term memory or subconscious memory tasks show little change over time and with increasing age. There can be various reasons for confusion or disorientation. Medication, psychiatric disturbance, or retirement can confuse the individual. For some older people, retirement means creating a new set of routines and adjusting to them. Most elderly adults like structure in their lives and have familiar routines for approaching each day.

GERIATRIC RADIOGRAPHY

Demographics and Social Effects of Aging

Physical, Cognitive, and Psychosocial Effects of Aging

GERIATRIC RADIOGRAPHY