(1)

Radiology Department Beijing You’an Hospital, Capital Medical University, Beijing, People’s Republic of China

15.1.1 HIV/AIDS Related Retinitis

15.1.3 Herpes Virus Induced Lesions

15.1.4 Toxoplasma Retinitis

15.1.5 Other Infections

15.1.6 Eye Neoplasms

Abstract

In patients with AIDS, over 90 % have ocular manifestations of opportunistic infections and over 70 % have accompanying signs of oculopathy. CMV infection is the most common HIV/AIDS related oculopathy and PCP, tuberculosis, HSV infection, fungus infection, toxoplasmic infections and Kaposi’s sarcoma rarely occur. Oculopathy is commonly opportunistic infections, with involvement of both intraocular and extraocular tissues. Concurrent infections may be found, such as concurrence of fungal infection and CMV infection. Some oculopathies occur in the early stage of AIDS, being an indicator of HIV infection. With the prolonged course of the illness, the occurrence of complications increases.

15.1 Introduction to HIV/AIDS Related Oculopathy

In patients with AIDS, over 90 % have ocular manifestations of opportunistic infections and over 70 % have accompanying signs of oculopathy. CMV infection is the most common HIV/AIDS related oculopathy and PCP, tuberculosis, HSV infection, fungus infection, toxoplasmic infections and Kaposi’s sarcoma rarely occur. Oculopathy is commonly opportunistic infections, with involvement of both intraocular and extraocular tissues. Concurrent infections may be found, such as concurrence of fungal infection and CMV infection. Some oculopathies occur in the early stage of AIDS, being an indicator of HIV infection. With the prolonged course of the illness, the occurrence of complications increases.

15.1.1 HIV/AIDS Related Retinitis

HIV/AIDS related fundus microvascular lesions is also known as HIV/AIDS related retinitis, which may result in retinal capillary occlusion, retinal nerve fiber necrosis, microaneurysms and flaky retinal hemorrhage, with cotton-wool liked exudating plaques or round/oval Roth plaques with white centers. Ophthalmoscopy demonstrates white cotton wool liked effusions at the posterior end of the retina, with unclearly defined boundary. The old lesions are in lightened color in whitish gray with clearly defined boundary. The absorbed white plaques have remained slight retinal pigment disorder. The pathological changes of retinal microvascular lesions include: (1) vascular endothelial cells swelling; (2) globulin sedimentation or increased immune complexes; (3) increased blood viscosity; (4) cellular necrosis surrounding blood vessels and thickened basal membrane of endothelia cells. Pathological examination suggests immune complexes sedimentation, followed by microvascular occlusion and local ischemia. In addition, edema, degeneration, necrosis and rupture of the nerve fiber can be found, with swelling of neural terminals.

15.1.2 Cytomegalovirus (CMV) Infection

In patients with AIDS, disseminative CMV infection is common, with a death rate of 30 % directly from CMV infection. In the advanced stage of AIDS, CMV may involve eyes. The incidence rate of HIV/AIDS related CMV retinitis is about 10–15 %, and about 30 % by autopsy. With the prolonging of the survival period, its incidence is increasing. Retinitis is a local manifestation of disseminative CMV infection, with characteristics of chronic and progressive necrosis of the whole retina (necrotic retinitis) with following blindness after several months’ progression. Its clinical manifestations include unilateral visual field defect or decreased vision, sense of floating materials or dark spots in front of eyes. By ophthalmoscopy, typically large yellowish white opaque foci scatter along the vascular vessels. Sometimes, the accompanying inflammatory effusion or bleeding surrounding vascular vessels may occur, with necrosis at the focal center. The necrotic retina and normal retina are clearly defined, with yellowish white particles at the margin of the foci. At the early stage, the lesions are found at the peripheral area of the fundus, with light gray cotton wool liked exudates of blurry borderline, which extends later to the macula and the optic papilla. Macular edema can lead to decreased vision, with retinal congestion and edema or even hemorrhage and necrosis in the active phase in tomato sauce liked appearance of the fundus. The active lesions are grayish white at the edges with a rapid progression while lightened color at the edges of foci. The small granules are relatively static. Meanwhile, the foci can gradually enlarge, possibly with newly occurring foci. It has been reported that the foci may enlarge 1–2 times within 1 month. CMVR is a complication in terminal AIDS patients, which usually occur in cases with CD4+ T count being less than 0.05 × 109/L. At this level of CD4 T count, the incidence of CMVR is about 24.6 %. It can be manifested as a sudden outbreak or regional granular. The pathological basis is that retinal microvascular lesions cause local insufficiently of blood supply and formation of cotton wool liked plaques. The foci of the infection distribute along vascular vessels. Commonly, CMV invades blood vessels to cause toxemia, leading to multi-focal infection. Invasion of CMV into retinal gliocytes and pigment epithelial cells renders CMV to duplicate actively in them to cause irreversible damages to the infected cells. Therefore, necrosis of large areas of retina occurs. For cases of AIDS have blurry vision or sense of floating materials in front of eyes, fundus examination should be performed under dilated pupil. CMV retinitis typically occurs at the retinal peripheral area or at the posterior pole, commonly with hemorrhage and vascular inflammatory changes. Thereby, in the year of 1987, CDC of the United States listed CMV retinitis as an indicator of AIDS in the diagnosis, with following diagnostic criteria: specific changes by ophthalmoscopy such as scattered retinal white effusions with blurry boundaries disseminating along the blood vessels centrifugally. Its progression lasts for several months, with occurrence of accompanying retinal vasculitis, hemorrhage and necrosis. After acute lesions subside, the retinal scars and atrophy remain with accompanying retinal pigment epithelial spots. CMV retinitis is irreversible. Isolation of CMV from the patient’s aqueous humour and tear is of diagnostic value. PCR technology has high specificity and sensitivity, facilitating the diagnosis of pathogen.

15.1.3 Herpes Virus Induced Lesions

Herpes virus induced lesions are commonly caused by Herpes simplex virus( HSV) and varicella-zoster virus (VZV) infections, both of which can lead to acute retinal necrosis with a rapid progression. Within 2–4 days, the whole retina can be completely destroyed. The foci are grayish white, with clearly defined borderline. Such patients usually have a recent history of herpes zoster or herpes simplex infection.

15.1.4 Toxoplasma Retinitis

Toxoplasma retinitis is usually congenital or can be found in patients with AIDS. Retinochoroiditis initially occurs, with lesions in the peripheral area of the fundus in the early stage. In the following stages, the foci may involve macula and optic papilla. Fundus examination indicates singular or multiple light yellow retinal lesions at the fundus at the acute phase, being irregular in shape. It may develop into necrotic retinochoroiditis, chronic choroiditis or optic neuritis, with accompanying vitreitis.

15.1.5 Other Infections

Other infections include tuberculosis, pneumocystosis, cryptococcal and bacterial infections, which may result in conjunctivitis, cornea ulcer and meibomian gland cyst. Viral infections usually lead to molluscum contagiosum and in children lead to a typical viral skin infection, which can involve eyelid and conjunctiva. Molluscum contagiosum is clinically manifested as grayish white nodules at the eyelids, 2–3 mm in diameter with a central hilar depression. Herpes zoster is also common.

15.1.6 Eye Neoplasms

Kaposi’s sarcoma commonly occurs at the eyelids and conjunctivas of AIDS patients, with an incidence rate of about 20–24 %. It can be found in the tissues of eyelids, tarsal gland, lacrimal gland and conjunctiva. The diseased eyelids may have light purple colored lesion or bright/dark red flat plaques and nodules, with involvement of both upper and lower eyelids. The lesions are confined painless nodules, with local lumps which gradually enlarge. The conjunctival lesions are relatively flat, being prone to be confused with subconjunctival hemorrhage and nodules. Orbital involvement causes exophthalmos, blepharoedema, and ptosis of the upper eyelid.

15.2 HIV/AIDS Related Orbitopathy

15.2.1 HIV/AIDS Related Intraorbital Mucormycosis

15.2.1.1 Pathogen and Pathogenesis

Mucor spores are commonly found in soil and air, which can be inhaled into nasal sinus and lung. It seldom causes disease in healthy populations and mucormycosis occurs commonly in immunocompromised people and is generally secondary. The pathogen invades the body through nasal mucosa where black necrotic foci are formed. Then they spread around and extend to the orbit of the same side to involve eyeballs, intraorbital soft tissues, blood vessels and nerves. Mucor invasion into ophthalmic artery can cause thrombosis that further leads to facial, orbital content and eyelid infarction as well as local skin gangrene.

15.2.1.2 Pathophysiological Basis

HIV/AIDS related orbital mucormycosis is not the same as other mycoses which have a chronic progression. It is an acute inflammation with a rapid progression to trigger extensive dissemination. It spreads to the surrounding tissues rapidly, commonly invading blood vessels to cause thrombosis and infarction. Sometimes the illness is chronic, with multitude macrophages and foreign giant cells, infiltration of massive neutrophils and eosinophils, interstitial fiber hyperplasia and thickened capillary walls. The necrotic area, vascular wall, vascular lumen and thrombosis contain quantities of mucor hyphas. HIV/AIDS related orbital mucormycosis is manifested as acute suppurative inflammation, which has a more severe invasion to the blood vessels than aspergillus to cause a higher occurrence of vascular thrombosis and infarction. Therefore, severe necrosis and purulence of the tissues might be the results of concurrence direct action of mucor and vascular blockage by mold embolus.

15.2.1.3 Clinical Symptoms and Signs

Clinically the ocular symptoms include orbital pain, eyelid ptosis, exophthalmos, fixation and loss of sight, orbital infection (cellulitis) companied with exophthalmos, pus discharge from the nasal cavity, possible damage of nasal septum, roof of the mouth (palate), orbital bones or sinus tract. The pathogens may also invade major blood vessels to cause thrombosis and necrosis. Death may rapidly occur in such patients.

15.2.1.4 Examinations and Their Selection

1.

Direct microscopic examination and culture of fungus: The specimens are collected from superior turbinate scrapings or biopsy.

2.

Histopathological examination facilitates the qualitative diagnosis.

3.

CT scanning and MR imaging facilitate the shape of the occupied space and its surrounding tissues.

15.2.1.5 Imaging Demonstrations

CT scanning demonstrates an increase in orbital density, loss of posterior fat space of eyeballs and exophthalmos, diffuse shadows of increased density at the orbital conical area, effusion in nasal cavity and maxillary sinus, mucosal hypertrophy of maxillary sinus and ethmoidal sinus, curved nasal septum. The severely ill patients may develop orbital cellulitis, suggesting of pathogenic invasion into eyes and the central nervous system to cause paralysis of multiple cranial nerves such as V and VII.

Case Study

A male patient aged 43 years was confirmatively diagnosed as having AIDS by CDC. He had a history of paid blood donation and his CD4 T cell count was 55/μl.

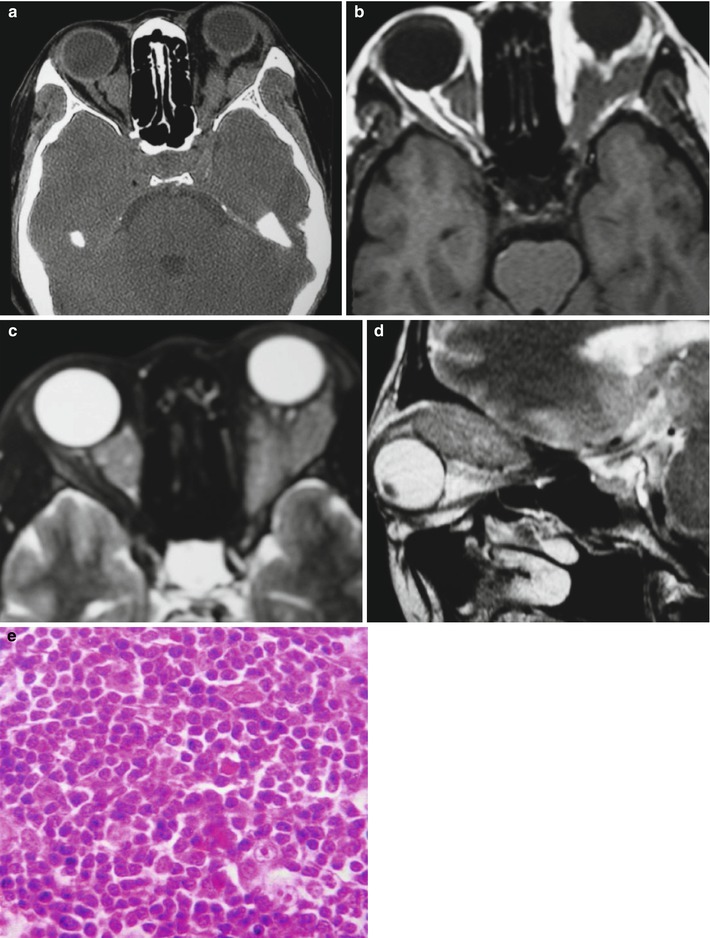

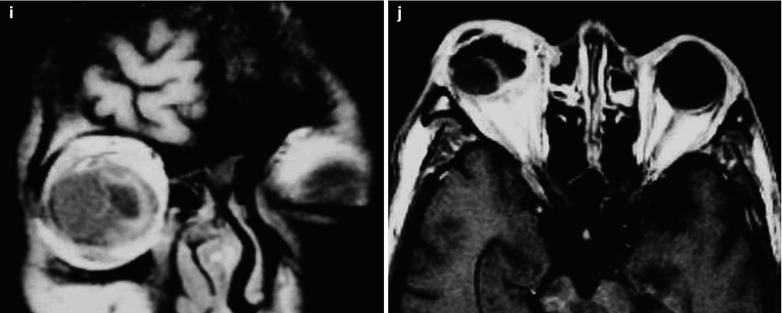

Fig. 15.1

(a–d) HIV/AIDS related mucormycosis. (a–b) CT scanning demonstrates increased tissues density in the left eye, deformed eyeball and diffuse shadows of increased density at the orbital conical area. (c) CT scanning demonstrates liquid level of the left maxillary sinus, mucosa hypertrophy of the right maxillary sinus and ethmoidal sinus, and curved nasal septum. (d) Pathological analysis of perforated tissues indicates light staining of hyphas with varied diameters

15.2.1.6 Criteria for the Diagnosis

1.

Etiological examinations

2.

Histopathological examinations

It usually demonstrates suppurative inflammation companied with abscess formation and suppurative necrosis. The necrotic tissue may contain broad hyphas, with peripheral narrow band of neutrophils. Chronic infection rarely occurs, with common manifestations of simplex granuloma or concurrent purulent inflammation and granuloma inflammation. Invasion of blood vessels by pathogens may be found, with vascular wall necrosis, fungal embolism and tissue infarction.

3.

CT scanning and MRI imaging

CT scanning and MR imaging demonstrate intraorbital space occupying effects, loss of orbital posterior fat space and protruding eyeball due to compression.

15.2.1.7 Differential Diagnosis

Patients with normal immunity usually have chronic nasal mucormycosis with local nasal granuloma containing hyphae. In some patients, only cranial or cerebral granuloma occurs, with demonstrations of intracranial space occupying effects. The immunocompromised patients with AIDS rarely have granuloma, making it difficult to be identified from other fungal infections and bacterial infections. Therefore, the diagnosis should be based on the etiological examinations.

15.2.2 HIV/AIDS Related Intraorbital Lymphoma

15.2.2.1 Pathogen and Pathogenesis

Compromised immunities caused by AIDS, some hereditary diseases, acquired immunodeficiency diseases or autoimmune diseases such as ataxia telangiectasia, combined immunodeficiency syndrome, rheumatoid arthritis, systemic lupus erythematosus, hypogammaglobulinemia and patients receiving long-term immunosuppressing medication (such as medication after organ transplantation) are high risks for occurrence of non-Hodgkin’s lymphoma.

15.2.2.2 Pathophysiological Basis

According to the latest classification, orbital lymphoma is categorized into non-Hodgkin’s lymphoma, accounting for about 0.01 % in patients with lymphoma and 3 % in patients with extraglandular malignancies. It can occur in conjunctiva and lacrimal gland or posterior to eyeballs, complicating central nervous system lymphoma. It occurs in patients aged above 30 years, with homogeneously yellowish or pinkish masses. Its inside lobule is obvious, with clearly defined borderline. The neoplasms have a uniform shape, composed of immature lymphocytes or evidently deformed lymphocytes. The tumor cells are in diffusive infiltration, with various morphologies. The tumor cells may be atypical T lymphocytes in different sizes, concurrently exist with possible involvement of the blood vessels.

15.2.2.3 Clinical Symptoms and Signs

It is clinically manifested as unilateral or bilateral swelling and ptosis of the eyelids, with palpable painless hardened lumps. The eye ball bulges, migrating laterally. Chemosis occurs, with infiltrative hyperplasia to involve optic nerves and extraocular muscles. In the cases with invasion to subconjunctiva, lumps like pink fish can be observed through conjunctiva.

Non-Hodgkin’s lymphoma is a definitive illness of AIDS. Orbital lymphoma is commonly non-Hodgkin’s lymphoma (originating from B lymphocytes). It has a unilateral occurrence (more common) or bilateral concurrence (rarely found). Clinically, it can be divided into acute and chronic. The chronic type has a hideous onset, with slow progression and mild symptoms, while the acute type has clinical manifestations of eyelid swelling, palpable painless hardened nodular intraorbital lumps; propelled eyeballs out of the orbits, eyeballs motion disorders and decreased eyesight.

15.2.2.4 Examinations and Their Selection

1.

Ultrasonography.

2.

CT scanning

3.

MR imaging

4.

Pathological examinations provide essential evidence for the diagnosis of MHL and its category.

15.2.2.5 Imaging Demonstrations

B Ultrasound

The B mode ultrasonography demonstrates irregular lesions in flat or oval pattern with clearly defined borderline, less echoes, and decreased ultrasound attenuation. Generally, CDI can detect the relatively rich blood flow within the lesions.

CT Scanning

Lymphoma usually occurs in the extraconal space, with concurrent involvement of orbit and extraconal space. It has unclearly defined borderline with peripheral extraocular muscle and eye ring, with even density of orbital foci by CT scanning. Lymphoma shows a diffuse growth inside and outside of muscular cone, and grows encompassing eyeballs with a cast liked condition, whereas the eye ring is complete without confined thickening. The intraorbital fat space cannot be found. Enhanced scanning suggests mildly or moderately even enhancement. Based on the range of the involvement, lymphoma is divided into local and diffuse. (1) Most lesions are located anterior to the extraconal space, immediately posterior to orbital septum and anterior area of the orbital septum, with a growth tendency of encompassing eyeballs. (2) Unilateral lesions are common with rare occurrence of bilateral involvements. The lesions grow backward along extraconal space with a sharp posterior margin of the lump in a cast liked change. (3) Due to no envelope surrounding the tumors, the tumors have infiltrative growths, with no obvious mechanical space occupying effects. Therefore, it commonly involves extraconal space, with unclearly defined borderline with eye ring, extraocular muscle and optic nerve. The interface between the wall of eyeball and the tumor has no depression, with no obvious thickened eye ring. (4) Plain CT scanning demonstrates homogeneous density, similar to the density of the extraocular muscle. By enhanced scanning, moderately homogeneous enhancement of the tumors can be found. (5) Orbital bone injury is rarely found, but can be found in cases with lesions resulted from orbital lymphoma invasion. (6) In some cases, the lymphoma can spread to intracranial and extracranial areas via superior or inferior orbital fissure.

MR Imaging

Lymphoma commonly occurs in the extraconal space, with concurrent involvements of the orbit and extraconal space. It is unclearly defined from peripheral extraocular muscle and eye ring. Moreover, MRI shows equal T1 and long T2 signals and a moderate enhancement by enhanced imaging. Lymphoma often involves eyelid and the peripheral tissues of the orbit, with rare involvement of the orbit itself.

Case Study

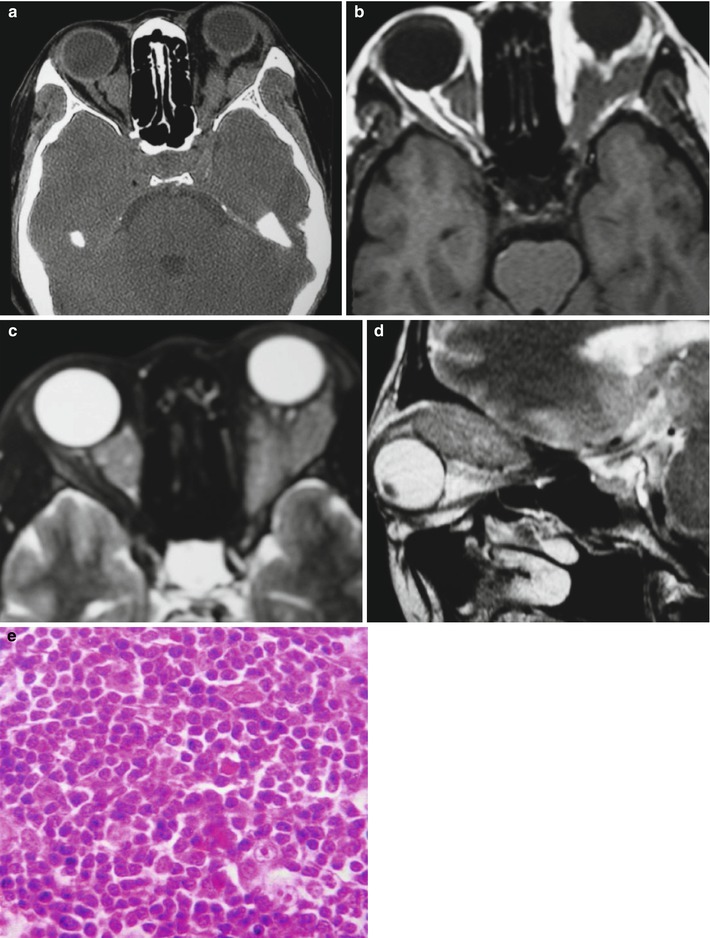

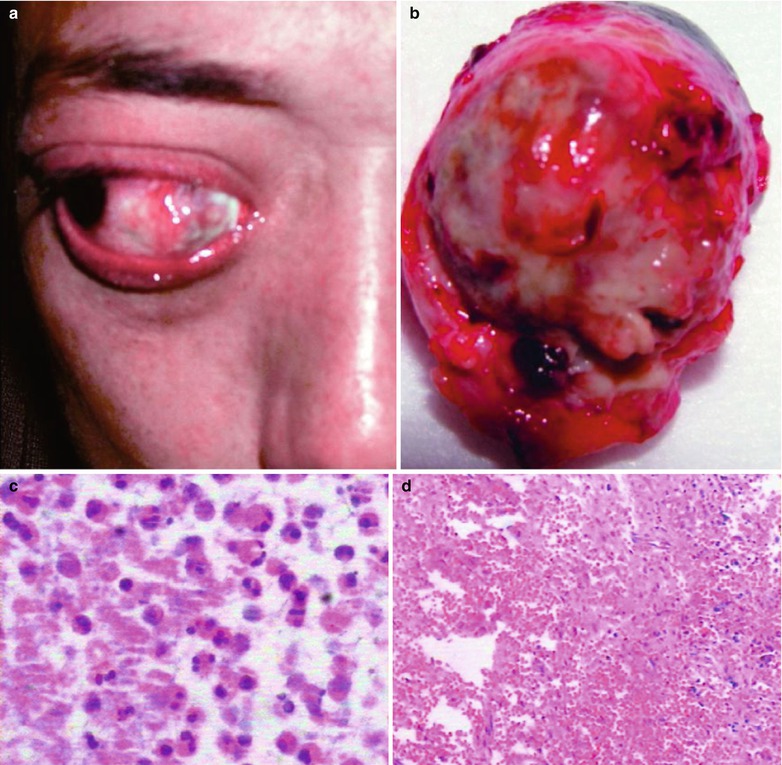

A female patient aged 54 years was confirmatively diagnosed as having AIDS by CDC. She had a history of paid blood donation and her CD4 T cell count was 15/μl.

Fig. 15.2

(a–e) HIV/AIDS related orbital lymphoma. (a) The bilateral orbits demonstrates irregular shaped mass shadows of soft tissues. (b, c) Axial MRI demonstrates equal T1 and long T2 signals of intraorbital soft tissues. (d) Sagittal MRI demonstrates spindle shaped soft tissue signals above optic nerves. (e) Pathological analysis of perforated tissues demonstrates mirror cells as a main type of lymphocytes

15.2.2.6 Criteria for the Diagnosis

1.

CT scanning demonstrates lump shadows of soft tissue density superior to the orbit and surrounding eyeballs have an unclearly defined borderline with their neighboring eyelid, extraocular muscle and lacrimal gland. The lumps are of homogeneous density with moderately even enhancement. The orbits are rarely involved.

2.

MR imaging indicates frequent occurrence of lymphoma in the extraconal space, with equal T1 and long T2 signals. Enhanced imaging demonstrates a moderate enhancement. The orbits are rarely involved.

3.

Biopsy of pathological tissues suggests mirror cells as a main type of lymphocyte.

15.2.2.7 Differential Diagnosis

Diffuse Inflammatory Pseudotumor

It commonly has an uneven density with extraocular hypermyotrophy. Its typical manifestations include simultaneous thickening of the muscular belly and tendon, companied by thickened eye ring and enlarged lacrimal gland. Hormone therapy is effective but it commonly recurs.

Orbital Cellulitis

The symptoms include swollen eyelid soft tissues with unclear borderline, swollen and thickened extraocular muscles. Enhanced scanning suggests inhomogeneous but evident enhancement of the foci. Thereby, diagnosis can be made in combination of its inflammatory manifestations. Its clinical medical history and blood biochemical examination has specific indicators.

Diffuse Lymphangioma

It generally has a long-term progression, with manifestations of large lumps, irregular shapes, uneven density, obvious enlargement and no damages to bones.

15.2.3 HIV/AIDS Related Fungal Suppurative Panophthalmitis

15.2.3.1 Pathogen and Pathogenesis

The vitreum is a tissue with no blood supplying, only containing water and protein. The invasion of pathogens and their duplication may cause inflammation and abscess. The pathogens are usually from eyelid and conjunctival sac, fungus accounting for 26 %. The invasion of pathogens into eyes and duplication there produces endotoxins and exotoxins which triggers violent inflammatory reactions of the ocular tissues. Thereby, a series of clinical symptoms show up.

15.2.3.2 Pathophysiological Basis

The common pathological changes include extensive suppurative inflammation, large quantities of neutrophils infiltration. Separated small abscesses adjacent to foci may be found. At the terminal phase, polymorphonuclear white cells encompass the fungus to trigger granuloma reactions.

15.2.3.3 Clinical Symptoms and Signs

According to the severity of clinical manifestations, endophthalmitis falls into three categories.

1.

Acute endophthalmitis The incubation period is about 3 days or just hours. The symptoms are severe, with a rapid progression, which is usually caused by staphylococcus aureus, pseudomonas aeruginosa and bacillus cereus with strong virulence.

2.

Sub-acute endophthalmitis The incubation period is about 1 week. The symptoms are evident, caused by streptococcus and diplococcus pneumonia.

3.

Chronic endophthalmitis The incubation period is over 1–2 weeks. The symptoms are slight, with a slow progression or recurrence. The pathogens include staphylococcus epidermidis, staphylococcus albus, fungus and propionibacterium acnes with weak virulence.

Suppurative endophthalmitis and endophthalmitis induced by bacillus cereus commonly have a sudden outbreak, which should be given focused attention.

15.2.3.4 Examinations and Their Selection

1.

Bacterial culture and smear staining of aqueous humour and the vitreum is of critical value for the definitive diagnosis.

2.

Ultrasound can identify the severity of vitreous opacity, retinal detachment and presence of bulbar wall or retrobulbar abscess, which is key for the diagnosis and treatment.

3.

CT scanning demonstrates heterogeneously moderate density, with the eye rings bulging inward and deformed.

4.

MR imaging is of high resolution for soft tissues, which can provide more information about the tissue structure for the diagnosis.

15.2.3.5 Imaging Demonstrations

B Ultrasound

B ultrasound demonstrates spot or strip liked echo of the vitreum and posterior high intensity echo band connected to the optic disc, which indicates retinal detachment.

CT Scanning

CT scanning demonstrates enlarged eyeballs with uneven density and unclear borderline with peripheral tissues. The eye ball bulges inward with obvious deformity.

MR Imaging

MR imaging demonstrates equal T1 and long T2 signals of eyeballs, deformed eyeball, thickened eye ring and enhanced signaling from the vitreum. IV-GD-DT-PA demonstrates obviously ring shaped abnormal enhancement of retrobulbar lumps.

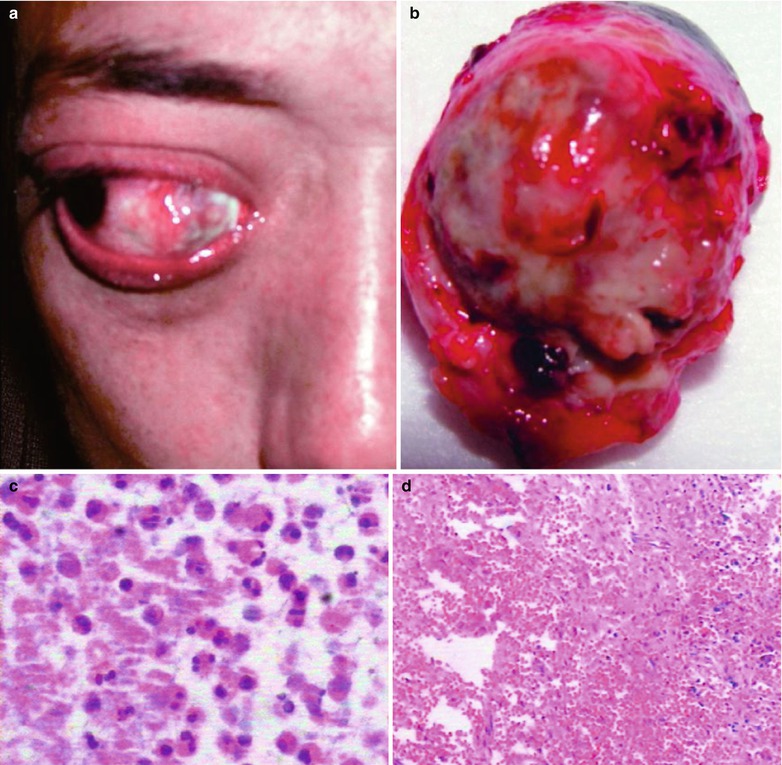

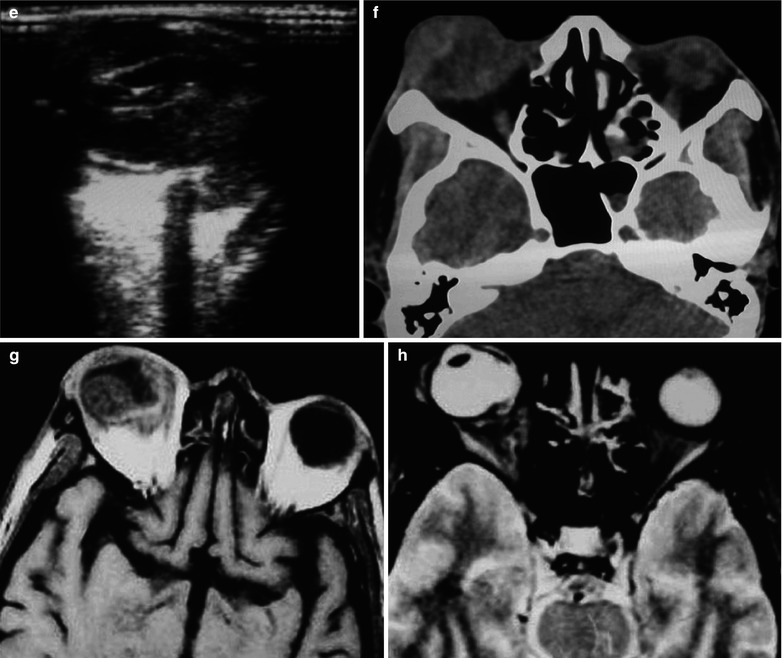

Case Study

A male patient aged 31 years was confirmatively diagnosed as having AIDS by CDC. He had a history of paid blood donation, with a progressive loss of right eyesight and bulging eye ball with pain for 1 month. His CD4 T cell count was 75/μl.

Diagnosis: AIDS complicated by fungal suppurative panophthalmitis and interior staphyloma.

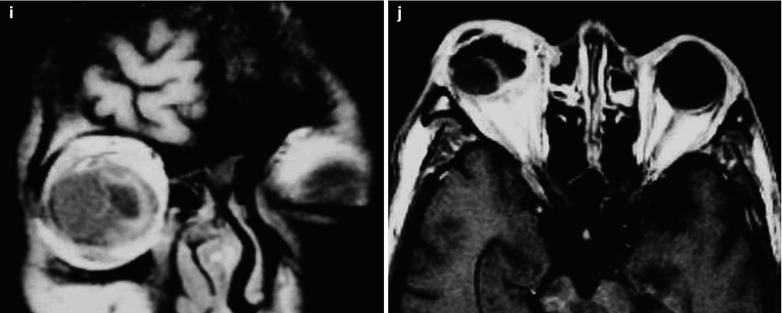

Fig. 15.3

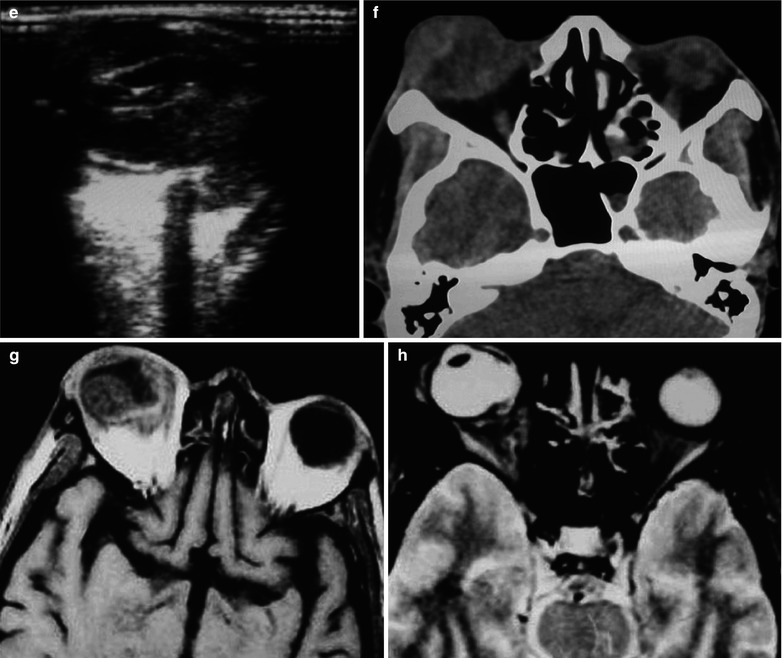

(a–j) HIV/AIDS related fungal suppurative panophthalmitis and interior staphyloma. (a) Right eyeball protruding outward with exterior rotation as well as ocular medial masses. (b) Manifestations before and after enucleation of the right eyeball, with abscesses and protrusion of the medial sclera to cover the surface of the eyeball. (c) Pathological analysis demonstrates inflammatory necrotic tissues in the ocular infected area, with congestion and small vessel hyperplasia; chronic suppurative necrosis in the ocular abscess area with abundant neutrophils and local acidophils; blood clots in the ocular necrotic tissues and melanin deposit in the cavity wall with obvious congestion. (d) Massive inflammatory necrotic tissues and fungal hyphae with slight staining. (e) B ultrasound demonstrates spot and strip liked echo in the vitreum and posterior light bands with strong echo connected to the optic disc, indicating retinal detachment. (f) CT scanning demonstrates heterogeneously moderate density area in size of 2 × 2 cm in the right eye, with the eye ring protruding inward and deformed eyeball. (g, h) MR imaging demonstrates equal T1 and long T2 signal posterior to the eyeball. (i) Coronal MR imaging demonstrates enlarged and deformed right eyeball, with heterogeneous signaling from the vitreum. (j) MRI IV-GD-DTPA demonstrates retrobulbar masses with obviously ring shaped enhancement but no central enhancement

15.2.3.6 Criteria for the Diagnosis

B Ultrasound

B ultrasound demonstrates spot and strip liked echo in the vitreum, with posterior light band of high intensity connected to the optic disc, indicating retinal detachment.

CT Scanning

CT scanning demonstrates enlarged eyeballs with uneven density and vague borderline with peripheral tissues, inward bulging eye ring and obviously deformed eyeball.

MR Imaging

MR imaging demonstrates equal T1 and long T2 signals of eyeballs, deformed eyeball, thickened eye ring and enhanced signaling from the vitreum. IV-GD-DT-PA demonstrates abnormal ring shaped enhancement of retrobulbar lumps but no central enhancement.

15.2.3.7 Differential Diagnosis

It should be differentiated from traumatic hemorrhage and ocular neoplasms.

15.2.4 HIV/AIDS Related Choroidal Tuberculosis

15.2.4.1 Pathogen and Pathogenesis

Choroidal tuberculosis falls into two categories according to the lesions nature. One is caused by direct invasion of tissues by mycobacterium tuberculosis. Due to the rich choroidal blood vessels and slow blood flow, bacteria are likely to remain there to cause choroidal tuberculosis. Therefore, choroidal tuberculosis is common in ocular tuberculosis. This type of choroidal tuberculosis is characterized by chronic proliferative lesions, with no severe inflammatory reactions. The other category is caused by direction invasion of other bacteria than mycobacteria, namely allergic responsive inflammation of tissues to tuberculoplasmin which is characterized by acute progression with evident inflammatory effusion.

15.2.4.2 Pathophysiological Basis

In the acute stage, the fundus usually presents yellowish white or grayish white exudative foci in round or oval shapes or circumscribed by satellite spots. It can be found across the fundus, but commonly in the peripheral area. For cases with prolonged course or renal pigment degeneration caused by other factors, retina-choroid barrier may be damaged with choroidal fluid accumulating under the retina to cause retinal detachment. Thereby it should be differentiated from primary retinal detachment. After inflammation subsides after treatment, shrinkage foci may be remained at the fundus, with pigment sedimentation. It may recur in the peripheral area of the foci or in the areas adjacent to the inflammatory lesions.

15.2.4.3 Clinical Symptoms and Signs

Clinical manifestations of tuberculous chorioretinitis can be divided into four types, namely exudative, chronic miliary tuberculosis, acute miliary tuberculosis and choroidal tuberculoma. Their clinical manifestations include: (1) concurrence of retinal tubercles with choroidal tuberculosis, (2) tuberculous retinitis with yellowish white exudative foci, hemorrhage and venectasia, (3) tuberculous retinal periphlebitis and (4) tuberculous retinal arteritis that has a rare occurrence, with white effusions and tuberculous choroiditis in the retinal arteries.

15.2.4.4 Examinations and Their Selection

Ultrasonography

B ultrasound demonstrates retrobulbar thickened sclera that protrudes towards vitreous space and retrobulbar abscess. Retina-choroid detachment occurs due to retrobulbar scleritis. Retrobulbar abscess surrounds the optic nerve in a T shaped sign. A ultrasound demonstrates thickened posterior eyeball wall showing a massive spike liked echo.

CT Scanning and MR Imaging

CT scanning demonstrates thickened posterior eye ring, thickened junction between the optic nerve and eyeball, concurrent exophthalmos and retrobulbar edema. Injection of contrast reagent can more clearly demonstrate the findings. MR imaging demonstrates thickened posterior eyeball wall with long T1 and T2 signals and enhanced imaging demonstrates enhancement. Signal intensity of weighted imaging can distinguish choroid and retina, which is of great value for the diagnosis of retrobulbar scleritis.

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree