(1)

Radiology Department Beijing You’an Hospital, Capital Medical University, Beijing, People’s Republic of China

19.2.3 HIV/AIDS Related Esophagitis

19.3.1 Pathogens and Pathogenesis

19.3.2 Pathophysiological Basis

19.3.3 Clinical Symptoms and Signs

19.3.5 Imaging Demonstrations

19.3.6 Criteria for the Diagnosis

19.3.7 Differential Diagnosis

19.4.1 Pathogens and Pathogenesis

19.4.2 Pathophysiological Basis

19.4.3 Clinical Symptoms and Signs

19.4.5 Imaging Demonstrations

19.4.6 Criteria for the Diagnosis

19.4.7 Differential Diagnosis

19.5.1 Pathogens and Pathogenesis

19.5.2 Pathophysiological Basis

19.5.3 Clinical Symptoms and Signs

19.5.5 Imaging Demonstrations

19.5.6 Criteria for the Diagnosis

19.5.7 Differential Diagnosis

19.6.1 Pathogens and Pathogenesis

19.6.2 Pathophysiological Basis

19.6.3 Clinical Symptoms and Signs

19.6.5 Imaging Demonstrations

19.6.6 Criteria for the Diagnosis

19.6.7 Differential Diagnosis

19.7.1 Pathogens and Pathogenesis

19.7.2 Pathophysiological Basis

19.7.3 Clinical Symptoms and Signs

19.7.5 Imaging Demonstrations

19.7.6 Criteria for the Diagnosis

19.7.7 Differential Diagnosis

Abstract

The gastrointestinal tract is one of the most involved organs by HIV/AIDS, with lesions in the mesentery, peritoneum and retroperitoneum. HIV/AIDS related gastrointestinal diseases can be divided into two types, including inflammations and neoplasms, such as CMV infection and KS. These diseases can involve all kinds of tissues in the digestive system. For instances, Candida mainly invades oral cavity and esophagus, while protozoa infection often involves colon to cause chronic diarrhea. KS commonly occurs in esophagus, followed by the small intestine and colon in frequency of occurrence. Lymphomas mostly occur in small intestine and colon.

19.1 An Overview of HIV/AIDS Related Gastrointestinal Diseases

The gastrointestinal tract is one of the most involved organs by HIV/AIDS, with lesions in the mesentery, peritoneum and retroperitoneum. HIV/AIDS related gastrointestinal diseases can be divided into two types, including inflammations and neoplasms, such as CMV infection and KS. These diseases can involve all kinds of tissues in the digestive system. For instances, Candida mainly invades oral cavity and esophagus, while protozoa infection often involves colon to cause chronic diarrhea. KS commonly occurs in esophagus, followed by the small intestine and colon in frequency of occurrence. Lymphomas mostly occur in small intestine and colon.

The common inflammatory diseases include:

1.

Candida infections

Candida albicans is the most common pathogen for esophageal infections in HIV/AIDS patients, with typical symptoms of swallowing pain and difficulty swallowing, progressive chest pain that may be severe. In the early stage, the lesions include small patchy filling defects in esophageal mucosa that distribute along the long axis of the esophagus, mucosal edema, and further brush liked change of the esophagus wall. Deep ulceration and mucus shedding are causes of irregular esophageal wall in its progressive stage.

2.

Spastic esophagitis

Clinically, based on esophageal spasm, spastic esophagitis can be diagnosed. It is favorably demonstrated by esophageal contrast radiography. The common demonstrations include multiple scattering superficial ulcers that distribute between normal mucosa.

3.

Cytomegalovirus infections

Cytomegalovirus esophagitis is a common complication in AIDS patients, with involvements of almost all segments of gastrointestinal tract. Infections of colon and small intestine are more common than infections of esophagus and stomach. Ulcer occurs due to local tissue ischemia induced by CMV. CMV esophagitis has common manifestations of discontinuous ulcers between normal esophageal mucosa. The definitive diagnosis depends on biopsy. CMV gastritis commonly involves gastric sinuses. By barium meal radiography, the gastric sinus wall is demonstrated to have nodular thickening, ring shaped stenosis of the gastric sinus cavity, and accompanying weakening dilation. CMV colonitis firstly is demonstrated as superficial ulcers. But with the occurrence of edema, mucosal folds are thickened, with enlarged and deepened ulcers.

4.

Tuberculous esophagitis

Tuberculous esophagitis is often derived by expanding of necrotic lymphoid tuberculosis within the mediastinum adjacent to the middle esophageal segment. Esophageal X-ray and CT scanning demonstrate local external lump impression, deep ulcer, sinus tract and fistula formation. Intestinal tuberculosis commonly involves ileocecus. By barium double contrast and radiography, there are ring shaped stenosis and ring shaped thickening of the ileocecus wall. In some cases, there is also formation of sinus tract, such as occurrence of urethrorectal fistula.

5.

Kaposi’s Sarcoma (KS)

KS is a kind of tumor derived from lymphatic reticuloendothelial cells. KS often occurs in homosexual/bisexual AIDS patients, with an incidence of up to 50 %. A KS related herpes virus (KS-HV) has been isolated from KS in patients of different ethnic groups, indicating its existence in KS. It involves different organs including, in frequency order, skin, lymph nodes, gastrointestinal tract, lungs, liver and spleen. The gastrointestinal tract is one of the most commonly involved organs, with typical manifestations of smooth submucosal nodules and accompanying/absent navel liked depression.

6.

HIV/AIDS related lymphomas

In patients with AIDS, about 10 % sustains NHL, which often occurs in superficial lymph nodes and mediastinal lymph nodes, especially in the esophagus, skeleton and abdominal organs, with no peripheral lymphadenectasis. Cases of gastric, intestinal or rectal lymphoma are demonstrated to have irregular thickening of the mucosal folds by barium meal radiography.

General introduction to HIV/AIDS related intestinal diseases:

1.

Small intestinal diseases

HIV/AIDS related small intestinal disease is commonly enteritis caused by opportunistic infection. The pathogen is cryptozoite and mycobacterium avium. And small intestinal infections caused by tubercle bacillus, salmonella and campylobacter jejuni are also common. The common symptoms include diarrhea or chronic diarrhea for four to five times a day, abdominal distension, nausea and spastic pain. Cryptozoite can only cause slight diarrhea among people with normal immunity that is self restraint lasting for 2–3 days. But in AIDS patients, it can cause severe diarrhea, such as cholera liked diarrhea. Mycobacterium avium can gain its access to the digestive tract via oral cavity to invade the small intestines, leading to fever and diarrhea.

2.

Colon and rectal diseases

The pathogens that cause colon and rectal infections in AIDS patients are commonly histolytic amebic protozoa, Giardia lamblia and herpes simplex (HSV). The other pathogens include cryptosporidium and cytomegalovirus, whose infections can cause colonitis that is common in AIDS patients. Cryptosporidium/cytomegalovirus infection induced colonitis is especially common in AIDS patients who are receiving antibiotic therapy. The clinical manifestations of colon and rectal diseases in AIDS patients are inflammation and perianal pain. Intestinoendoscopy demonstrates mucosal ulcers. The colon infection caused by cytomegalovirus (CMV) can lead to ulcer and perforation. Other related intestinal lymphomas and KS are more common in male homosexual patients with AIDS.

19.2 HIV/AIDS Related Viral Esophagitis

19.2.1 HIV/AIDS Related CMV Esophagitis

Cytomegalovirus infection, a common complication of HIV/AIDS, can lead to death. About 2–13 % AIDS patients have involvement of the gastrointestinal tract by CMV infection, leading to esophagitis, gastritis and colonitis. According to autopsy of CMV infected AIDS patients, about 90 % has explicit CMV infection and the cause of death is CMV infection in 40 % such patients. Studies have demonstrated that about 24 % AIDS patients have severe CMV infection within 2 years after the onset, which leads to occurrence of earlier death in AIDS patients. CMV infection in HIV/AIDS patients can involve all organs of the body, even the skin. But the commonly involved are the lungs, the central nervous system and the gastrointestinal tract. CMV pneumonia often causes death in patients with HIV/AIDS.

19.2.1.1 Pathogens and Pathogenesis

CMV belongs to the herpes virus family, and it can invade human body via various routes, including placenta, contacts, injection, blood transfusion, breathing, digestion, sexual intercourse and organ transplantations. AIDS patients are susceptible to CMV infection, with an incidence of up to 95 % in homosexual patients with AIDS. Generally, CMV remains a long-term incubation in the human body. CMV infection commonly occurs in immunocompromised population, with more than 90 % patients having CMV antibody positive and more than 50 % patients having virusemia. The compromised immunity occurs in AIDS patients due to HIV infection, while CMV can also have inhibitory effect on cellular immunity which worsens the immunity of AIDS patients.

19.2.1.2 Pathophysiological Basis

CMV infection often involves the adrenal gland, lungs and digestive tract, and it can also invade the spleen, lymph nodes, heart, thyroid gland, brain, pancreas, retina, liver, gall bladder, meninges, saliva gland, peripheral nerves, bladder, respiratory tract, larynx and other body organs. Klatt et al. retrospectively reviewed clinical data of 565 cases of AIDS [11]. It has been reported that CMV infection involved alimentary tract segments occurs in 165 cases (57.7 %), including 41 cases with esophageal involvement, 34 cases with gastric involvement, 40 cases with small intestine involvement and 43 cases with colorectal involvement. During the progression of HIV/AIDS, most patients sustain complications of active infections, with about 1/4 having life threatening serious infection. The characteristic pathology of CMV infection includes formation of cytomegaly and intranuclear virus inclusion bodies in owl’s eye sign. CMV antibody can be immunohistochemically marked for its demonstration. Atypical giant cells also have diagnostic value, which constitutes the criteria for the early diagnosis. In addition, there are also necrosis and shedding of local alimentary mucosal epithelial cells, degeneration and necrosis of tissues as well as mononuclear cells infiltration with accompanying necrotic focus.

19.2.1.3 Clinical Symptoms and Signs

The common clinical symptoms are fever and fatigue. Within 1–2 weeks after occurrence of fever, the absolute value of lymphocyte count in the blood increases, with heteromorphic changes and skin maculopapule. Esophagitis, gastroenteritis, splenomegaly and lymphadenitis (Table 19.1) can also occur.

Table 19.1

Alimentary diseases caused by CMV infection

Common diseases | Clinical manifestations |

|---|---|

Esophagitis | Difficulty swallow, retrosternal pain |

Gastritis | Epigastric pain, gastric ulcer |

Colorectal inflammation | Abdominal pain, diarrhea, poor appetite, weight loss and fever |

19.2.1.4 Examinations and Their Selection

1.

The definitive diagnosis of the disease depends on cytological and pathological examinations as well as virus culture. Brush cytology can be applied to collect samples for detection of inclusion bodies in the squamous epithelial cells. Using such procedure, the results can be obtained within 24 h. The positive rate is high in biopsy of specimens obtained by fibergastroscopy from the ulcers margin. In the advanced stage of the disease, it is difficult to harvest specimens. By virus culture, the results can be obtained within 24–72 h.

2.

By immunohistochemistry and in situ hybridization, the diagnosis can be made. By immunohistochemistry, the cytoplasm, nucleus and cytomegalic inclusion in the epithelial cells from lesions can be stained to show strong positive. In situ hybridization demonstrates the nucleus positively stained.

3.

The findings of serum anti-CMV antibody positive and IgM antibody positive can confirm the reactivation of current infection or latent infection. But the finding of serum IgG positive indicates a past infection.

4.

Using human fibroblasts to culture the patient’s specimens from surgical operation, blood, secretions and excretions, CMV can be isolated within about 4 weeks.

5.

Using the patient’s specimens from surgical operation, blood, secretions and excretions, CMV antigen can be detected. Its sensitivity to immunofluorescence can be up to 100 %.

6.

The finding of isolated ulcer in normal mucosa is characteristic by barium swallow examination. In the early stage, the ulcer is in shape of shallow round or oval. But in the advanced stage, the ulcer fuses to form plaque.

7.

In the early stage, gastroscopy demonstrates superficial and isolated small ulcers in the mucosa.

19.2.1.5 Imaging Demonstrations

Gastrointestinal Radiography

The direct signs include local or extensive CMV infection, with involvement of any segment of gastrointestinal tract to cause various lesions. The lesions include small and superficial erosion as well as deep ulcer and perforation. The indirect signs include esophageal irritation.

Direct Signs by Esophagoscopy

There are obvious congestion and edema in the mucosa of esophageal wall as well as crisp mucosa that tends to bleed when touched. There are also erosion or different sizes of ulcers, and even perforation.

Case Study

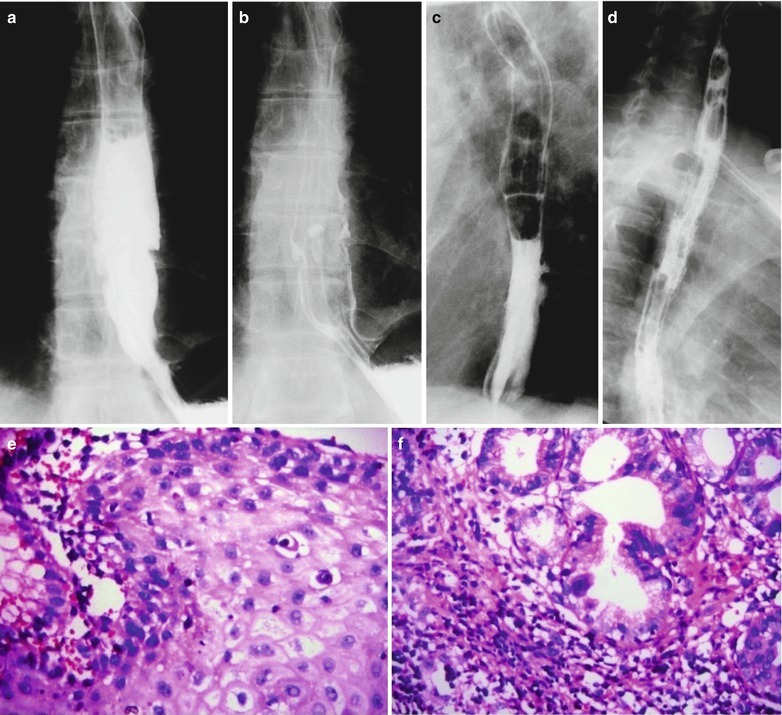

A male patient aged 34 years was confirmatively diagnosed as having AIDS by the CDC. He complained of retrosternal intermittent unsmooth swallowing for half a year, burning and progressive odynophagia for 6 weeks. His CD4 T cell count was 9/μl

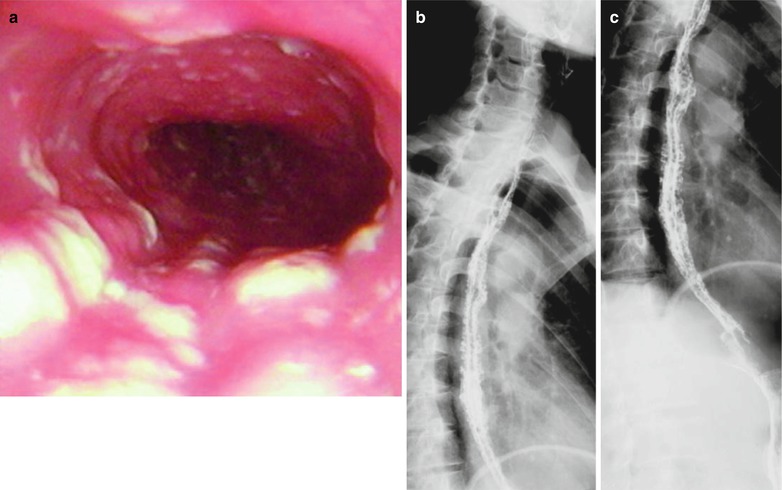

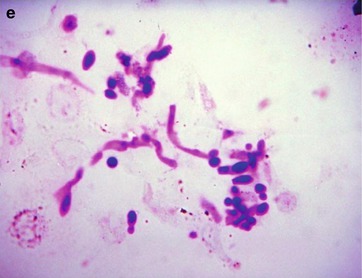

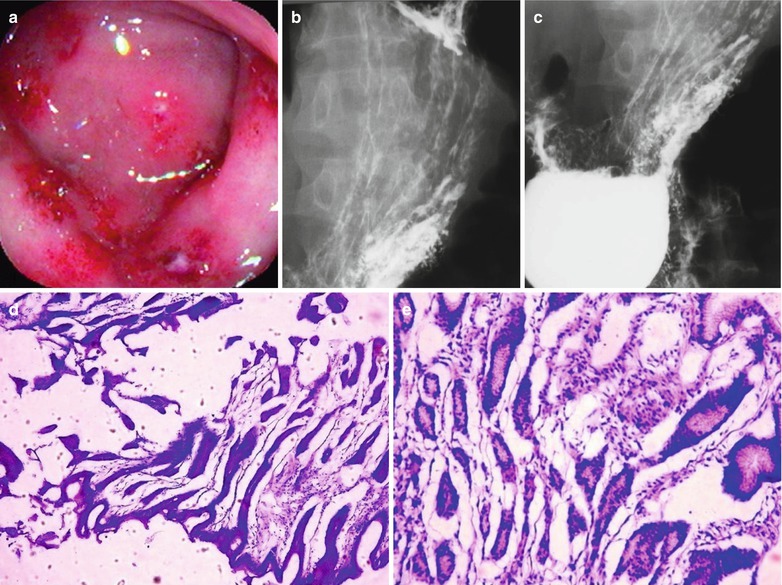

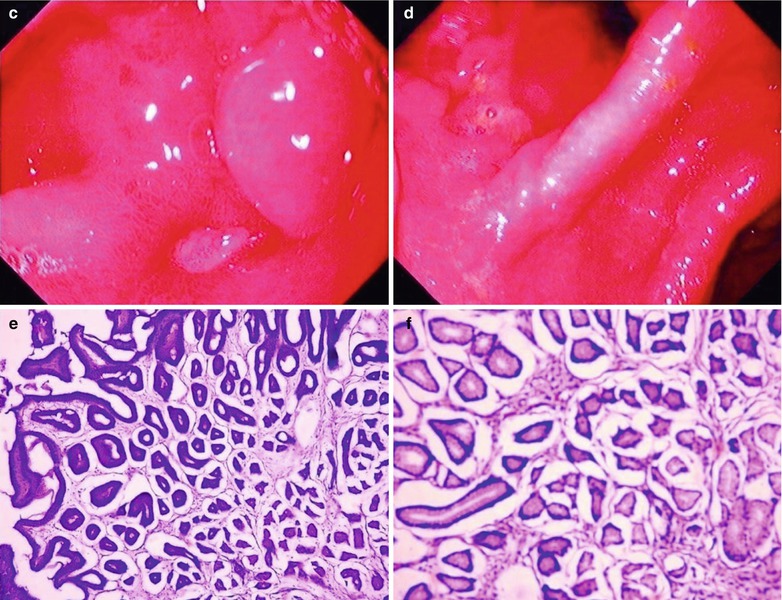

Fig. 19.1

(a–f) HIV/AIDS related CMV esophagitis. By esophageal barium meal radiology: (a, b) It is demonstrated to have normotopic barium meal filling sign and mucosa sign, indicating a niche liked filling defect and barium plaque in the lower part of the esophagus. (c) It is demonstrated to have right anterior oblique view of barium meal filling sign and mucosal niche liked barium plaque protrusion, with small burr shaped barium shadow. (d) It is demonstrated to have left anterior oblique view of coarse and unsmooth mucosa in middle and lower segments of the esophagus. (e) HE staining demonstrates cytomegalovirus inclusion bodies in the esophageal squamous epithelium (HE ×200). (f) HE staining demonstrates to have cytomegalovirus inclusion bodies in the mucosa of the lower segment of the esophagus (HE ×200)

19.2.1.6 Criteria for the Diagnosis

Clinical Symptoms

CMV esophagitis has common symptoms of retrosternal foreign sense, retrosternal pain, odynophagia and dysphagia as well as esophageal bleeding. Slight infection commonly is asymptomatic.

Endoscopy

At the dismal esophagus, there are small blisters, hole liked ulcers of various sizes, obvious congestion and edema in the fundus, crisp mucosa that tends to bleed when touched.

Biopsy

Biopsy of ulcers demonstrates acute/chronic inflammation, with findings of cytomegalovirus inclusion bodies. Biopsy in the early stage for virus culture has positive findings.

Esophageal Barium Meal Radiology

It demonstrates multiple scattered superficial ulcers, in manifestations of multiple patch liked filling defect and spike liked small ulcers.

Cytomegalorirus

There is increased titer of cytomegalovirus antibody in AIDS patients.

19.2.1.7 Differential Diagnosis

HIV/AIDS related CMV esophagitis should be differentiated from HSV esophagitis, candidal esophagitis and esophageal burn lesions.

19.2.2 HIV/AIDS Related HSV Esophagitis

19.2.2.1 Pathogens and Pathogenesis

The pathogen of viral esophagitis is herpes viruses. Therefore, viral esophagitis is also known as herpetic esophagitis. Currently, it is believed that the pathogens are commonly herpes simplex virus I and II, herpes zoster virus (HZV), CMV and EBV, in which HSV is more common. HSV can reach the esophagus along the vagus nerve to cause mucosal herpes lesions, which is common in immunocompromised and AIDS patients. The pathogenesis of herpes virus induced esophagitis is still in disagreement. Some scholars believe that the virus causes subintimal inflammation of the capillaries, arterioles and venules, with occurrence of thrombus to cause local necrosis and the resulted mucosal ulcers.

19.2.2.2 Pathophysiological Basis

HSV can reach esophagus along the vagus nerve to cause mucosal herpes lesions. The earliest pathological changes include focal ulcers. Generally, the disease can be divided into three stages. In the first stage, multiple small blisters occur at the distal esophagus. In the second stage, the small blisters fuse into swelling in size of 0.5–2 cm.

19.2.2.3 Clinical Symptoms and Signs

The common symptoms include retrosternal foreign sense and pain, odynophagia and dysphagia as well as occasional esophageal bleeding. Slight infections are usually asymptomatic. During the epidemic of the virus, cases with general soreness and pain, sore throat and accompanying esophageal symptoms should be diagnosed as having virus esophagitis (Table 19.2).

Table 19.2

Digestive diseases caused by HSV infection

Common diseases | Manifestations |

|---|---|

Pharyngitis and esophagitis | Dysphagia, substernal pain |

Colon and rectal inflammation | Anus and rectum pain, abdominal pain, diarrhea, poor appetite, weight loss, tenesmus, constipation, sacral abnormal feeling |

19.2.2.4 Examinations and Their Selection

1.

The definitive diagnosis of the disease depends on cytological and pathological examinations as well as virus culture.

2.

By immunohistochemistry and in situ hybridization, the diagnosis can be made.

3.

In situ hybridization should be performed with DNA probe of the herpes simplex virus. By immunohistochemistry, the cytoplasm, nucleus and cytomegaly inclusion of lesions epithelial cells are all stained strongly positive. By in situ hybridization, the nucleus is positive.

4.

By esophageal barium swallowing examination, isolated superficial ulcers are characteristic findings.

5.

By gastroscopy, small isolated superficial ulcers can be found in mucosa in the early stage of the disease, in sizes ranging from several millimeters to several centimeters.

6.

Biopsy.

19.2.2.5 Imaging Demonstrations

Gastrointestinal Radiography

The direct signs include characteristic isolated ulcers by double contrast esophageal radiography, in shallow round or oval shape in the early stage and fusion of ulcers into plaques in the advanced stage. The indirect signs include esophageal irritation.

Esophagoscopy

Esophagoscopy demonstrates hole liked ulcers of different sizes in the distal segment of the esophagus, and normal mucosa between ulcers. There are obvious congestion and edema in the mucosa in the early stage of the disease, and fusion of ulcers in the advanced stage. The mucosa is crisp, with diffuse damages and bleeding.

19.2.2.6 Criteria for the Diagnosis

1.

Clinical symptoms include general soreness and pain, sore throat and upper gastrointestinal tract symptoms with accompanying esophageal symptoms.

2.

By endoscopy, there are small blisters in the distal esophagus, hole liked ulcers of different sizes and normal mucosa between ulcers.

3.

Scattering and multiple superficial ulcers by esophageal barium radiology of double contrast.

4.

Biopsy and culture can confirm the diagnosis.

19.2.2.7 Differential Diagnosis

Cytomegalovirus Esophagitis

CMV infection is commonly complicated by infections of HSV, fungus and bacteria.

HZV Infection

VZV can cause necrotic esophagitis, and it can also lead to disseminated visceral infections.

HIV/AIDS Related Virus Esophagitis

The infected localizations have multiple ulcers, with symptoms of fever, diarrhea and odynophagia.

Papilloma Virus Infection

It can cause wart and flat condyloma of the squamous epithelium.

19.2.3 HIV/AIDS Related Esophagitis

Some chronic inflammation of the gastrointestinal tract and diarrhea show no evidence of pathogenic infection. It has been speculated that HIV may directly affect the intestinal environmental balance, which are known as idiopathic HIV/AIDS related intestinal diseases.

19.3 HIV/AIDS Related Candida Esophagitis

19.3.1 Pathogens and Pathogenesis

Candida albicans is a kind of conditional pathogenic fungi. The weakened immunity or the dysfunctional bacterial colonies cause candida albicans to be pathogenic fungi to cause candida infection. The incidence of candida infection is 80–90 %. The lesions commonly are found in the oral cavity, throat, esophagus and lungs. In AIDS patients, about 20 % has candida esophagitis. It is ulcerative pseudomembranous esophagitis caused by invasion of candida albicans to the esophageal mucosa. Such patients’ CD4 T cell count are commonly lower than 350/μl.

19.3.2 Pathophysiological Basis

Candida is a kind of conditional pathogen and Candida albicans is the main pathogenic type. Candida invades into the blood to cause candidemia, and then disseminated to visceral tissues and organs to cause multiple abscesses and chronic inflammation. The esophageal mucosa is found to have congestion, swelling, necrosis and even ulceration.

19.3.3 Clinical Symptoms and Signs

Clinical symptoms are pharyngalgia, odynophagia and dysphagia. Most patients have accompanying epigastric distention, hiccups, poor appetite and other gastrointestinal symptoms.

19.3.4 Examinations and Their Selection

1.

By digestive endoscopy, there are irregular ulcers and white pseudomembrane in the esophageal mucosa.

2.

Among various imaging examinations, barium meal radiography is of choice.

3.

Digestive endoscopy.

4.

Biopsy for pathological examination.

19.3.5 Imaging Demonstrations

19.3.5.1 Digestive Radiography

Esophageal X-ray of double contrast demonstrates (1) A wide range of involvement with different degrees of severity, increasingly serious involvements from the top to the bottom of the esophagus; (2) Abnormal dynamic changes including reduced tension and weakened peristalsis of all involved esophagus segments that are more obvious in lower esophagus, and delayed emptying; (3) Contour profile abnormalities including slight stenosis of the involved esophageal lumen as well as rough and irregular esophageal wall with brush liked sign; (4) Mucosal abnormalities including unevenly thickened mucosa, and scattering irregular filling defects of varying sizes on the surface of the thickened mucosa in cobblestone liked sign.

19.3.5.2 Digestive Endoscopy

It demonstrates congestion and edema of the involved esophagus, unevenly scattering irregular yellowish white pseudomembranous plaques of different sizes covering the mucosal surface that are more obvious in the lower segment.

Case Study 1

A male patient aged 36 years was confirmatively diagnosed as having AIDS by the CDC. He had symptoms of fever, fatigue, emaciation, throat irritation, dysphagia or odynophagia and feeling of retrosternal burning. His CD4 T cell count was 145/μl

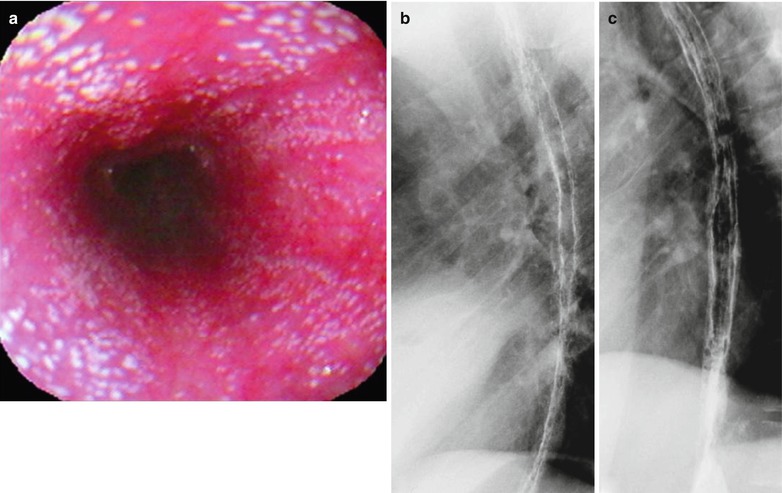

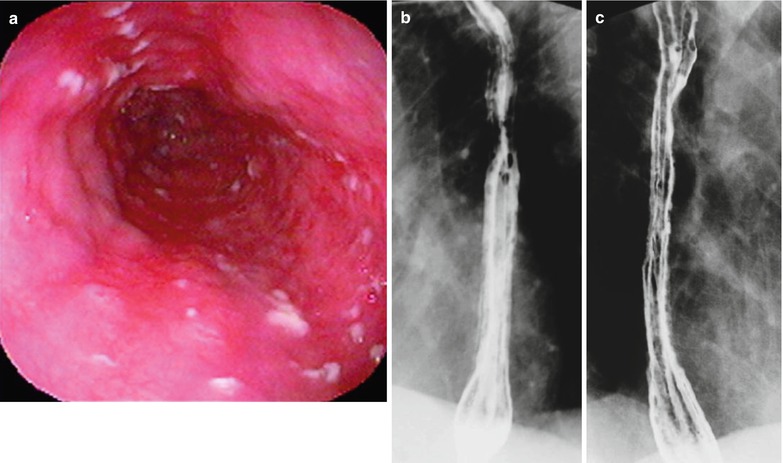

Fig. 19.2

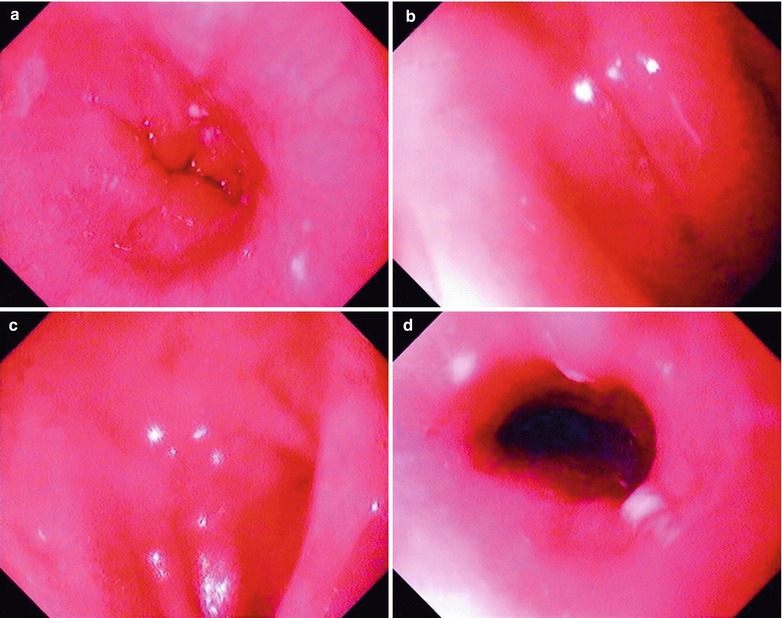

(a–c) HIV/AIDS related candida esophagitis. (a) Digestive endoscopy demonstrates mucosal congestion and edema in all segments of the esophagus, scattering yellowish white pseudomembranous plaques of different sizes adhering to the mucosa that is unable to be detached. (b–c) Esophagus barium meal radiology demonstrates thickened esophageal barium meal mucosa, narrowed lumen and blurry borderlines in lace liked sign or sawtooth liked sign

Case Study 2

A male patient aged 38 years was confirmatively diagnosed as having AIDS by the CDC. He had symptoms of fever, fatigue, emaciation, throat foreign sense, dysphagia or odynophagia, and retrosternal burning sense. His CD4 T cell count was 85/μl

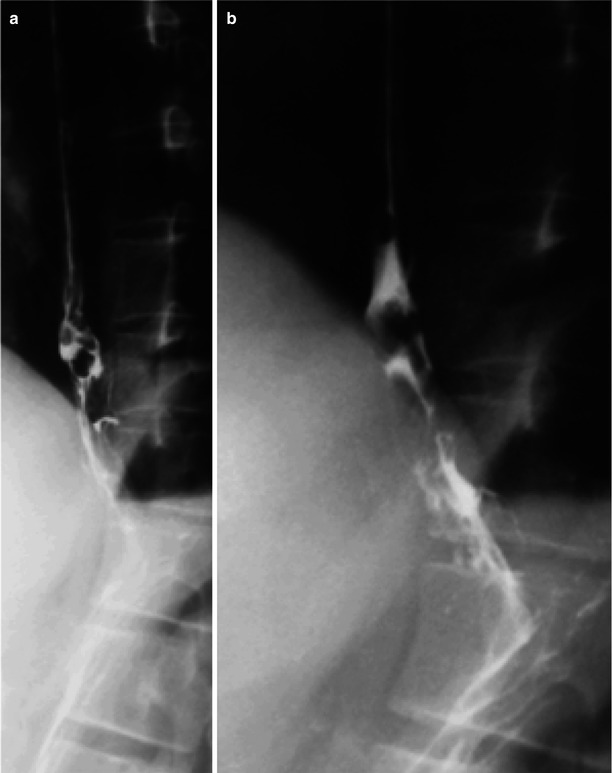

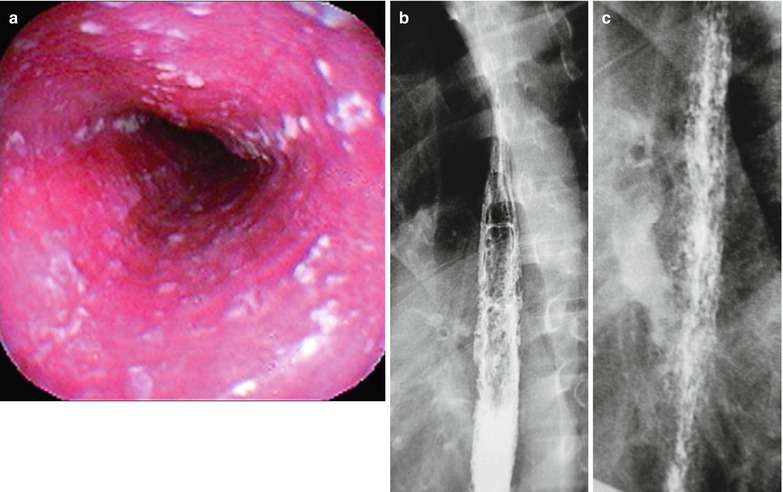

Fig. 19.3

(a, b) HIV/AIDS related candida esophagitis. (a, b) Esophagus barium meal radiology demonstrate thickened mucosa of the middle and lower segments of the esophagus, plaque liked filling defects, narrowed lumen, blurry and irregular borderline

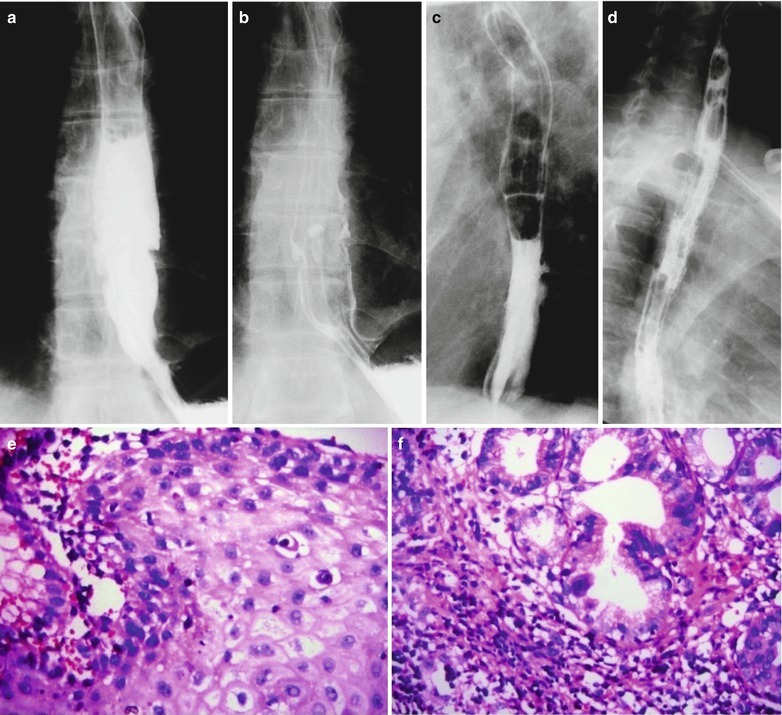

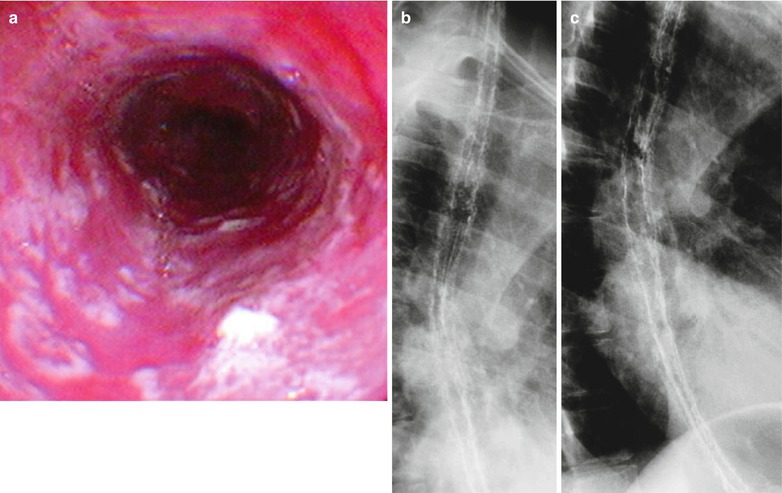

Case Study 3

A male patient aged 17 years was confirmatively diagnosed as having AIDS by the CDC. He had symptoms of fever, sense of foreign substance in the throat, dysphagia and retrosternal sense of burning. His CD4 T cell count was 40/ μl

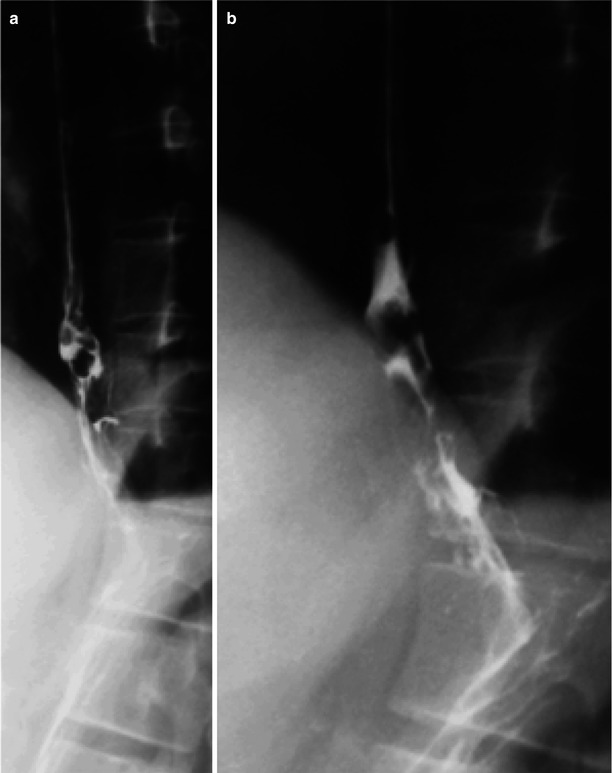

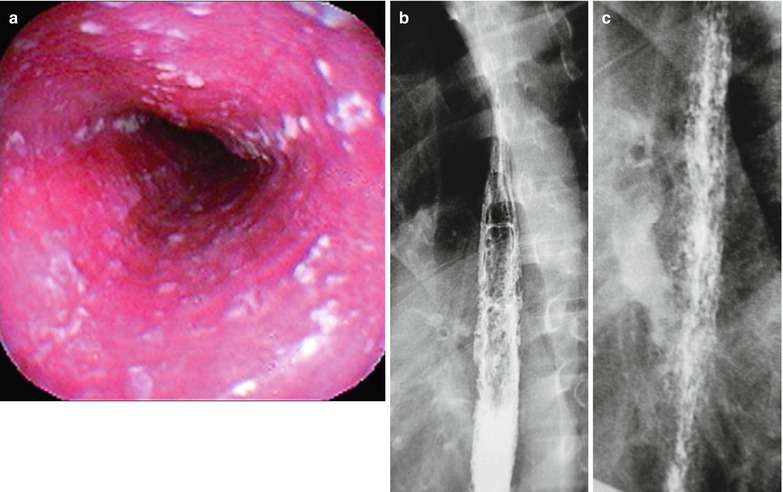

Fig. 19.4

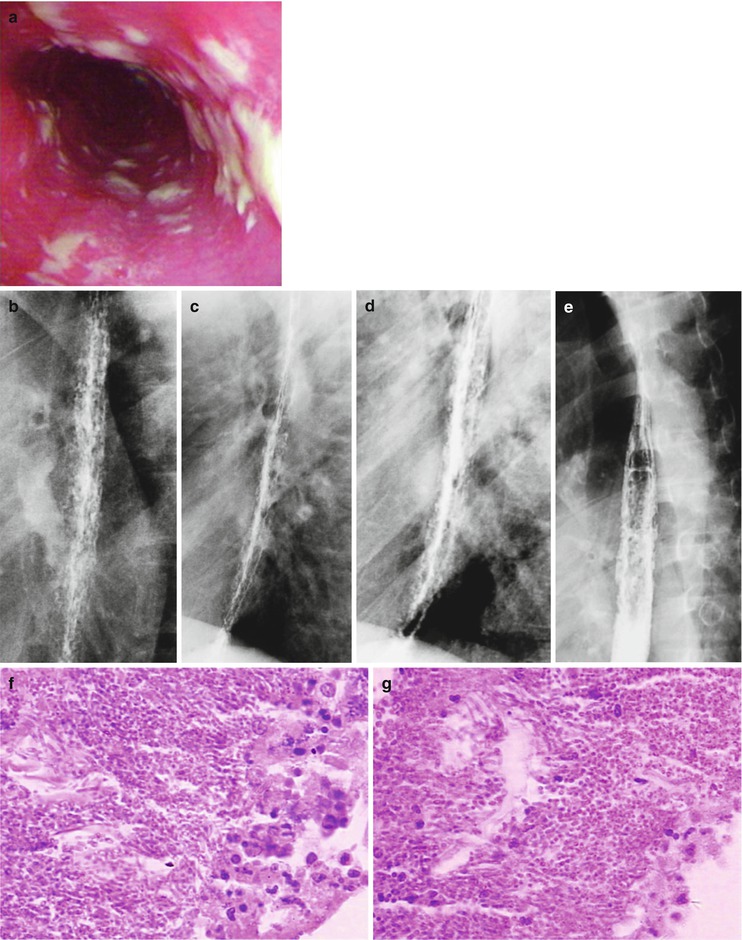

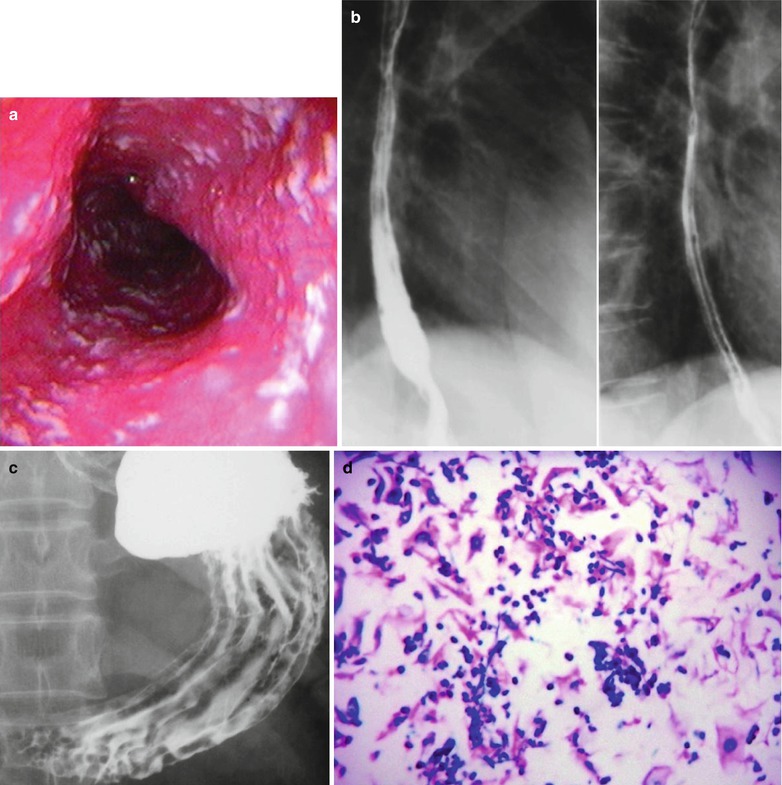

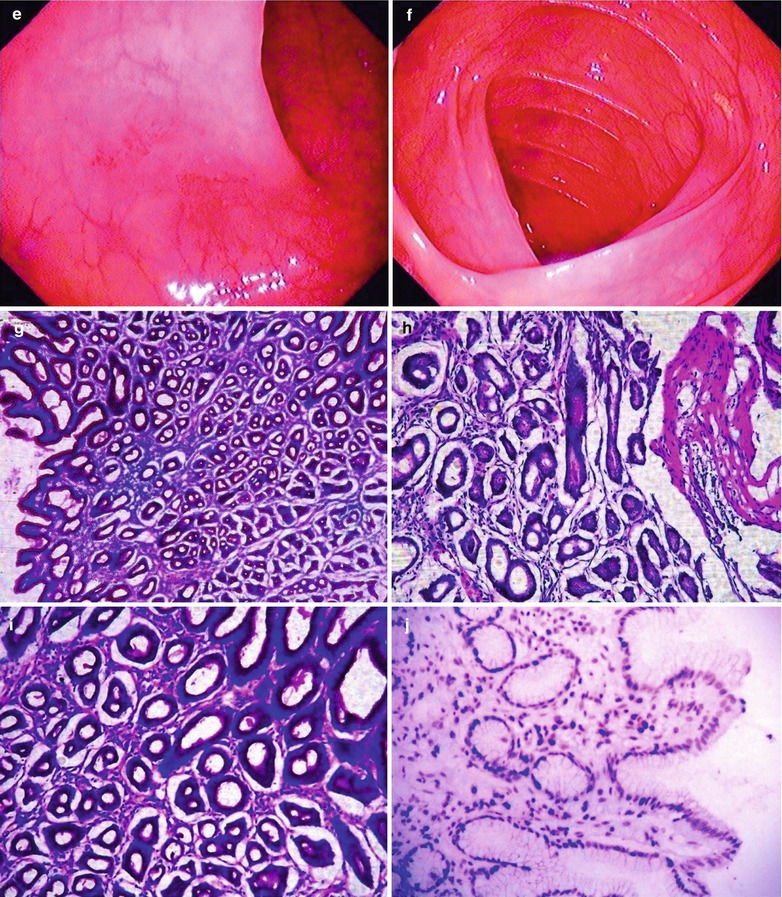

(a–g) HIV/AIDS related candida esophagitis. (a) Gastroscopy demonstrates mucosal congestion and edema of all segments of the esophagus, and scattered yellowish white pseudomembranous plaques of varying sizes adhering to the mucosa. (b–e) Esophagus barium meal radiology demonstrate thickened esophageal mucosa, narrowed lumen, blurry and irregular borderline, with lace liked sign or snake skin liked sign. (f–g) Biopsy and pathological tissue analysis demonstrate growth of large quantity cadida that is consistent with cadida infection

Case Study 4

A female patient aged 45 years was confirmatively diagnosed as having AIDS by CDC. She had symptoms of fever, emaciation and dysphagia. Her CD4 T cell count was 80/μl.

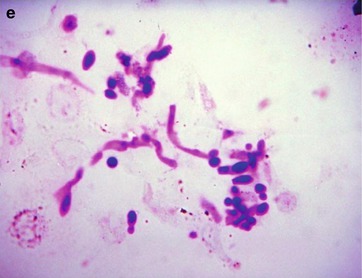

Fig. 19.5

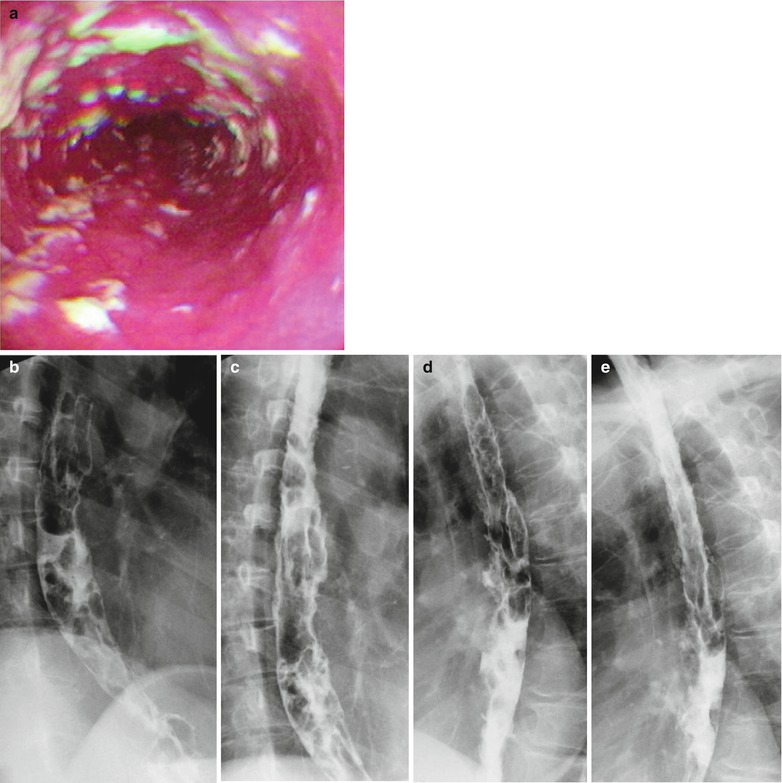

(a–e) HIV/AIDS related candida esophagitis. (a) Gastroscopy demonstrates mucosal congestion and edema in all segments of the esophagus, and scattered yellowish white pseudomembranous plaques of varying sizes adhering to the musosa. (b–e) Esophagus barium meal radiology demonstrate thickened esophageal mucosa, multiple flaky filling defects in the lumen, blurry and irregular borderline

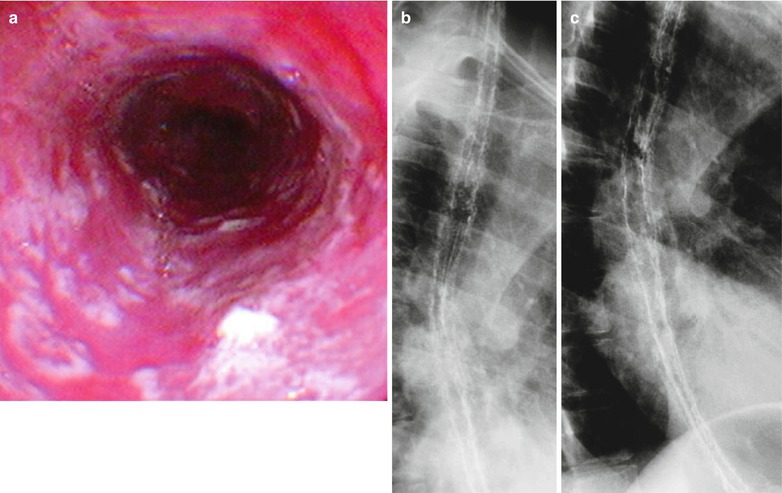

Case Study 5

A female patient aged 30 years was confirmatively diagnosed as having AIDS by CDC. She had symptoms of fever, Sense of foreign substance in the throat, dysphagia and retrosternal sense of burning. Her CD4 T cell count was 115/ μl.

Fig. 19.6

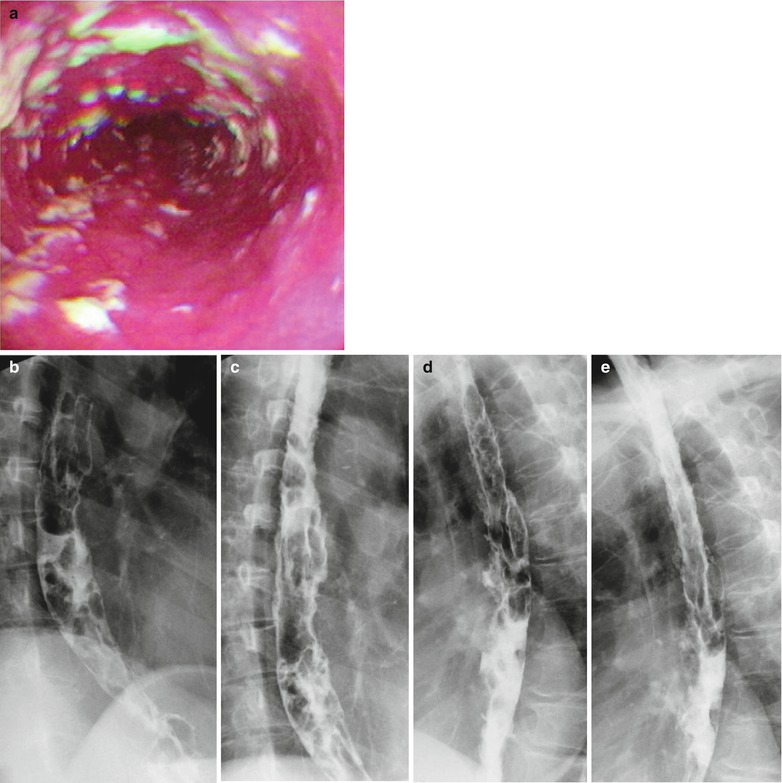

(a–c) HIV/AIDS related candida esophagitis. (a) Gastroscopy demonstrates mucosal congestion and edema of all segments of the esophagus, and scattered yellowish white pseudomembranous plaques of varying sizes adhering to the mucosa. (b, c) Esophagus barium meal radiology demonstrate thickened esophageal mucosa, multiple spots filling defects, narrowed lumen, blurry and irregular borderline in lace liked sign or snake skin liked sign

Case Study 6

A female patient aged 39 years was confirmatively diagnosed as having AIDS by CDC. She had symptoms of fever, emaciation, sense of foreign substance in the throat, odynophagia, and retrosternal sense of burning. Her CD4 T cell count was 115/μl.

Fig. 19.7

(a–c) HIV/AIDS related candida esophagitis. (a) Gastroscopy demonstrates mucosal congestion and edema of all segments of the esophagus, and scattered yellowish white pseudomembranous plaques of varying sizes adhering to the mucosa. (b, c) Esophagus barium meal radiology demonstrate thickened esophageal barium meal mucosa, multiple spots filling defects, narrowed lumen, blurry and irregular borderline in lace liked sign or snake skin liked sign

Case Study 7

A female patient aged 50 years was confirmatively diagnosed as having AIDS by CDC. She had symptoms of high fever, fatigue, sense of foreign substance in the throat, dysphagia and odynophagia. Her CD4 T cell count was 15/μl.

Fig. 19.8

(a–c) HIV/AIDS related candida esophagitis. (a) Gastroscopy demonstrates mucosal congestion and edema of all segments of the esophagus, and scattered yellowish white pseudomembranous plaques of varying sizes adhering to the mucosa. (b, c) Esophagus barium meal radiology demonstrate thickened esophageal barium meal mucosa, multiple spots filling defects, narrowed lumen, blurry and irregular borderline, with lace liked sign or snake skin liked sign

Case Study 8

A male aged 38 years was confirmatively diagnosed as having AIDS by CDC. He had symptoms of fever, sense of foreign substance in the throat, dysphagia and retrosternal sense of burning. His CD4 T cell count was 55/μl.

Fig. 19.9

(a–c) AIDS-related Candida esophagitis. (a) Gastroscopy demonstrates mucosal congestion and edema of all segments of the esophagus, and scattered yellowish white pseudomembranous plaques of varying sizes adhering to the mucosa. (b, c) Esophagus barium meal radiology demonstrate thickened esophageal mucosa, multiple spots filling defects, narrowed lumen, blurry and irregular borderline, with lace liked sign or snake skin liked sign

Case Study 9

A female patient aged 42 years was confirmatively diagnosed as having AIDS by CDC. She had symptoms of high fever, sense of foreign substance in the throat and dysphagia. Her CD4 T cell count was 85/μl.

Fig. 19.10

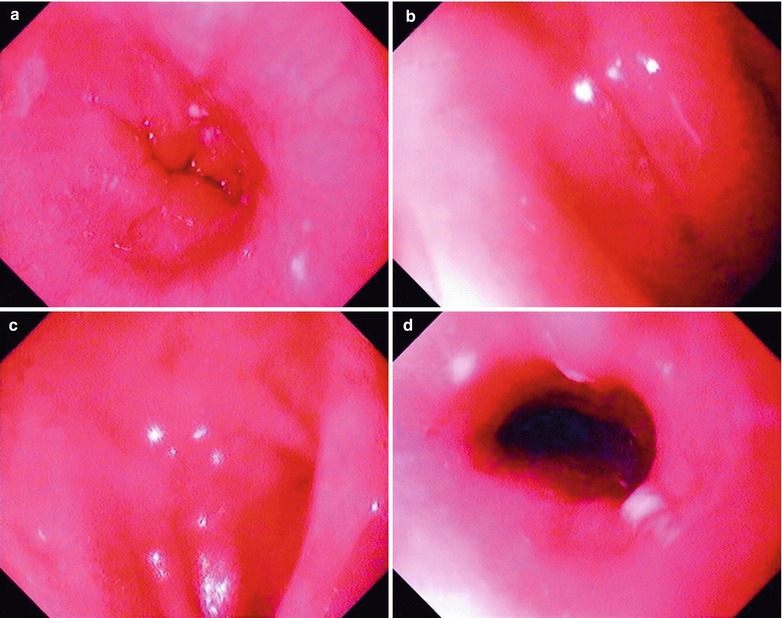

(a–c) HIV/AIDS related candida esophagitis. (a) Gastroscopy demonstrates mucosal congestion and edema of all segments of the esophagus, and scattered yellowish white pseudomembranous plaques of varying sizes adhering to the mucosa. (b) Esophagus barium meal radiology demonstrates thickened esophageal mucosa, multiple spots filling defects, narrowed lumen, blurry borderline with lace liked sign or snake skin liked sign. (c) Esophagus barium meal radiology demonstrates coarse gastric mucosa, and multiple round filling defects gastric body and antrum. (d) HE staining demonstrates candida albicans in gastric mucosa (HE ×400). (e) PAS staining of the candida albicans in gastric mucosa demonstrates red spores and pseudohyphae of Candida albicans (×1,000)

19.3.6 Criteria for the Diagnosis

1.

The sensitivity of digestive radiography to pseudomembranous plaques is up to 90 %, with cobblestone liked filling defects.

2.

Gastroscopic demonstrations of mucosal congestion and edema as well as yellowish white pseudomembranous plaques are main evidences for the diagnosis of HIV/AIDS related candida esophagitis.

3.

Biopsy finding of yeast liked fungal pseudohypha is an important evidence for the diagnosis.

19.3.7 Differential Diagnosis

19.3.7.1 Cytomegalovirus Esophagitis

Esophageal X-ray of double contrast demonstrates cytomegalovirus esophagitis to have multiple flat mucosal ulcers in large diameters. Low density edema rings can be found around the ulcers.

19.3.7.2 Herpes Simplex Virus Esophagitis

Esophageal X-ray of double contrast demonstrates herpes simplex virus esophagitis to have multiple spots, ring shaped or linear mucous superficial ulcers, and low density edema rings around the ulcers.

19.4 HIV/AIDS Related Gastritis

19.4.1 Pathogens and Pathogenesis

Some chronic inflammation and diarrhea have no evidence of pathogen infections, which has been speculated to be related to direct effects of HIV on intestinal environmental balance. Such diseases are known as idiopathic HIV/AIDS related intestinal diseases. The causes of HIV/AIDS related gastritis can be divided into exogenous and endogenous. Generally, the pathogens that gain their access to the stomach to cause gastritis are exogenous, commonly including chemical factors, physical factors, bacteria (especially the Helicobacter pylori), virus and toxins. The pathogens that infect the gastric mucosa along with blood flow are endogenous, commonly including systemic infection, uremia, liver failure, respiratory failure and stress responses.

19.4.2 Pathophysiological Basis

Most foci of acute gastritis occur from the gastric fundus in appearance of petechia or ecchymosis that fuse into irregular small ulcers in sizes of 2–20 mm. The histologic lesions are restricted to the mucosa. The focus continuously progresses to involve the submucosa, even penetrate the serosa, leading to multiple hemorrhage of the gastric fundus and involvement of the gastric antrum.

19.4.3 Clinical Symptoms and Signs

The common clinical manifestations of acute gastritis are epigastric upset, pain, nausea, vomiting and poor appetite. In cases with accompanying enteritis, diarrhea occurs. Physical examinations may find epigastric slight tenderness, with short duration of several days. Chronic gastritis has no specific findings, commonly with poor appetite.

19.4.4 Examinations and Their Selection

1.

Gastroscopy in combination with direct vision biopsy is the main method for the diagnosis of chronic gastritis.

2.

Digestive tract radiography demonstrates no specific findings in most cases of chronic gastritis.

3.

Gastric juice analysis demonstrates chronic atrophic gastritis with dysfunctioning gastric acid secretion, which is more serious in cases with chronic atrophic gastritis in the body of stomach.

4.

Serum parietal cell antibody test and serum gastrin determination demonstrate serum parietal cell antibody positive and increased level of serum gastrin in most cases of gastritis in the body of stomach.

19.4.5 Imaging Demonstrations

19.4.5.1 Digestive Radiography

The direct signs include thickened gastric mucous, poor adhesion of barium. The indirect signs include accelerated gastric peristalsis or irritation signs.

19.4.5.2 Gastroscopic Demonstrations

Mucosal congestion and edema of the stomach, possibly with superficial ulcers.

Case Study 1

A male aged 28 years was confirmatively diagnosed as having AIDS by CDC. He has symptoms of epigastric upset, pain, nausea, vomiting and poor appetite. His CD4 T cell count was 34/μl.

Fig. 19.11

(a–j) HIV/AIDS related gastritis and duodenitis. (a) Gastroscopy demonstrates smooth esophageal mucosa, favorable peristalsis and mucosal edema. (b) Gastroscopy demonstrates measles liked changes of mucosa in the body of stomach, antral mucosa commonly in red and white with dominant color of red, multiple swelling lesions with central depression, smooth surface, favorable peristalsis, round pyloric ostium with favorable opening. (c–e) Gastroscopy demonstrates multiple flaky congestion of varying sizes in the duodenal lumen, and no erosion. (f) Gastroscopy demonstrates clearly defined dentate line in size of 0.1 cm × 0.2 cm, no varicosis at the esophageal gastric fundus, large quantity of turbid mucous fluid in the mucus pool. (g) PAS staining demonstrates HIV inflammation with infiltration of inflammatory cells and gland atrophy (PAS ×10). (h–i) PAS staining demonstrates dilated glandular cavity, mucosal hemorrhage, and infiltration of inflammatory cells in the muscularis mucosa, which is serious inflammation (PAS ×20). (j) Immunohistochemistry demonstrates lymphocyte HIV-1GP120 antigen positive in the gastric mucosa in yellowish brown (×200)

Case Study 2

A male patient aged 47 years was confirmatively diagnosed as having AIDS by CDC. He complained of epigastric upset, epigastric distention and poor appetite. His CD4 T cell count was 84/μl.

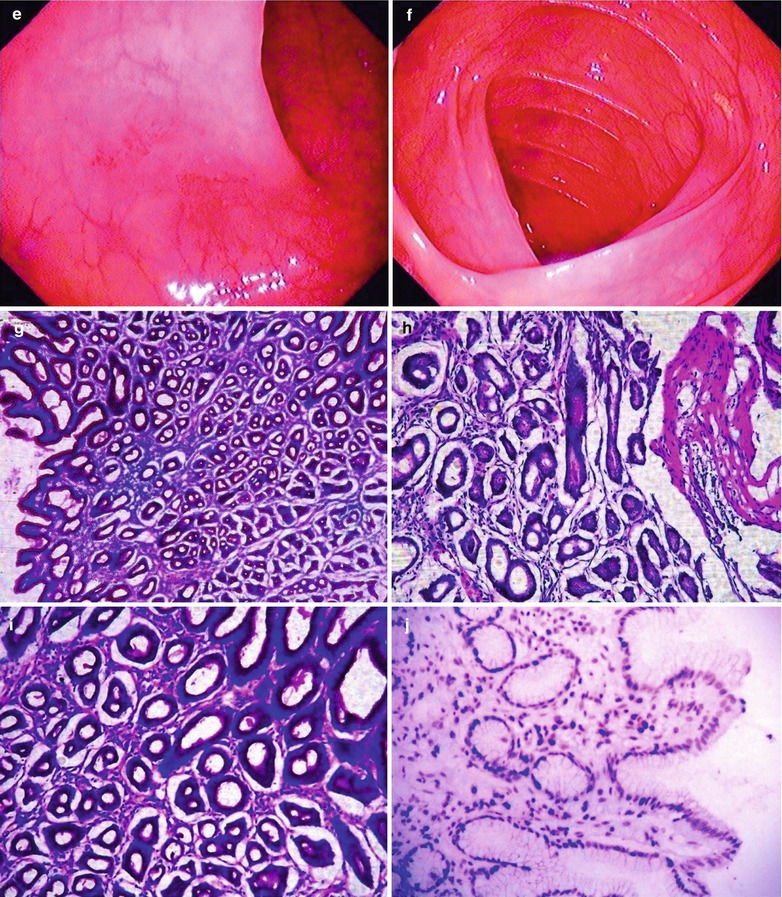

Fig. 19.12

(a–e) HIV/AIDS related gastritis. (a) Gastroscopy demonstrates multiple flaky milky white ulcers in the gastric mucosa, with flaky hemorrhagic plaques; (b, c) Esophagus barium meal radiology demonstrates thickened and coarse gastric mucosa; (d) PAS staining demonstrates dilated glandular cavities, mucosal hemorrhage, infiltration of inflammatory cells in the muscularis mucosa, which is severe inflammation (PAS ×10); (e) HE staining demonstrates dilated glandular cavities, mucosal hemorrhage, and infiltration of the inflammatory cells in the muscularis mucosa, which is severe inflammation (HE ×40)

19.4.6 Criteria for the Diagnosis

1.

The symptoms of chronic gastritis are nonspecific, with few signs.

2.

X-ray facilitates to diagnose the space occupying diseases of the stomach. The definitive diagnosis depends on gastroscopy and gastric mucosa biopsy.

3.

The diagnosis of chronic gastritis depends on histological changes and anatomic localization, with reference to immunological indices. The conference on chronic gastritis held in Chongqing, China in 1982 proposed a simple classification of gastritis: (1) superficial gastritis, with involvements of the surface and epithelium of the gastric mucosa, including symptoms of erosion and bleeding. Diffuse or confined should be defined. For cases of confined chronic gastritis, the localization of the lesions should be indicated. (2) Atrophic gastritis, with involvements of the glands in the deep mucosa to cause atrophy. (3) Hypertrophic gastritis. Its occurrence is still in controversy because there lacks supports by evidence of epithelial cells hypertrophy.

19.4.7 Differential Diagnosis

19.4.7.1 Peptic Ulcer

Both have chronic epigastric pain. Peptic ulcer has symptoms of epigastric regular periodic pain, while chronic gastritis has no regular pain, with common symptom of dyspepsia. Their differential diagnosis depends on barium meal radiology and gastroscopy.

19.4.7.2 Chronic Biliary Diseases

Chronic cholecystitis and cholelithiasis have symptoms of chronic right epigastric and abdominal distension, belching and some other symptoms of dyspepsia, which can be misdiagnosed as chronic gastritis.

19.5 HIV/AIDS Related Gastroduodenal Ulcer

19.5.1 Pathogens and Pathogenesis

HIV infection causes gastric mucosal inflammation and epithelial cell apoptosis. Studies have demonstrated that apoptosis may play an important role in the pathogenesis of HIV/AIDS related digestive diseases and gastric mucosal apoptosis index may not be related to local inflammation and Hp infection but to HIV itself and environmental changes of mucosal immune. Generally, it is believed that HIV/AIDS related gastroduodenal ulcer is caused by compound factors leading to vascular and muscular spasm of the gastroduodenal wall. The resulted cellular malnutrition of gastrointestinal wall and decreased defense of gastrointestinal mucosa cause the gastrointestinal mucosa being susceptible digestion by gastric juice to lead to ulcers.

19.5.2 Pathophysiological Basis

The lesions of HIV/AIDS related gastroduodenal ulcer are commonly found in similar localizations to typical duodenal ulcer in patients with normal immunity. The pathogenic process can be divided into three stages, including erosion, acute ulcer and chronic ulcer.

19.5.2.1 Erosion

Erosion is the shallow depression of the mucosa, and usually does not penetrate the muscularis mucosa. By naked eyes, erosion is the red spots with shallow depression, in diameters of less than 0.5 cm. By microscopy, the shallow erosion only involves the gland neck and sometimes muscularis mucosa. On the erosion fundus, there are few necrotic tissues and large quantity infiltration of neutrophils.

19.5.2.2 Acute Ulcer

Acute ulcers refer to those ulcers that penetrate the muscularis mucosa and involve the inferior layer of the mucosa. It can be derived from erosion, in diameters of less than 1 cm with clearly defined borderline. By microscopy, mucosa and muscularis mucosa are all destroyed and absent. The fundus of the ulcers is attached with small quantity necrotic tissues and small quantity fibrins and infiltration of many neutrophilic granulocytes.

19.5.2.3 Chronic Ulcer

About 15 % cases of duodenal ulcer are multiple, with accompanying gastric ulcer. By naked eyes, the ulcer fundus is attached by few exudates and necrotic tissues. Under a microscope, the ulcer is composed of 4 layers, namely inflammatory exudates, coagulative necrotic tissue, granuloma tissue and scar tissue.

19.5.3 Clinical Symptoms and Signs

HIV/AIDS related ulcers have common symptoms of pain, which is induced by HIV and other related factors. Pains from lesser gastric curvature ulcers mostly occur after the meals. Pains from duodenal ulcer and helicobacter pylori gastric ulcer usually occur in hunger and relieves after meals, which are similar to patients with gastric ulcers and normal immunity.

19.5.4 Examinations and Their Selection

19.5.4.1 Gastrointestinal Endoscopy and Biopsy

They can directly demonstrate the size and morphology of the lesions, and facilitate their qualitative diagnosis.

19.5.4.2 Diagnostic Imaging

Digestive radiography is a common examination for the diagnosis of ulcers. It can directly demonstrate the ulcer niche of the stomach and duodenum as well as its secondary organic and functional changes. It can also demonstrate different manifestations in different stages of ulcers, including its active stage and its healing stage. Virtual endoscopy by CT scanning or MR imaging has a limited application.

19.5.5 Imaging Demonstrations

19.5.5.1 Digestive Radiography

Gastric ulcer and duodenal bulbar ulcer are characterized by (1) Niche shadow, which is a direct X-ray demonstration for the diagnosis of duodenal ulcer. Duodenal bulbar ulcer mostly occurs in the anterior and posterior wall adjacent to the duodenal bulbar fundus, with surrounding transparent edema stripes that is gradually blurry towards the periphery, sometimes with short and fine mucosal markings whipping together. In cases of concurrent anterior and posterior wall ulcers in duodenal bulb, slight rotation can demonstrate two isolated barium plaques, known as kissing ulcers. (2) Deformity due to functional or organic changed caused by ulcer. The duodenal bulb commonly loses its normal morphology of triangular shape, and a variety of malformations occur, which is the common and important sign of bulbar ulcers. When the overall bulb spasm occurs, it demonstrates an irritative phenomenon. (3) Mucosal changes including the mucosal patterns in radial shape, whipping together towards the niche shadow. (4) Other changes including pyloric spasm, and duodenal ulcer lesions. Duodenal ulcer may progress into deep or surrounding tissues to penetrate the duodenal wall, leading to peripheral duodenal adhesion, narrowed and even obstructed passage, and other complications.

19.5.5.2 Gastroscopy

The lesions and their severity of gastric and duodenal ulcers can be determined by gastroscopy. From the most serious to slight, the disease can be divided into three stages and each stage can be subdivided into two periods. They are represented by A1, A2; H1, H2; and S1, S2.

1.

Acute stage can be subdivided into A1 and A2 periods. In A1 period, there are necrosis of the ulcer surface with coverage of thick white/yellow mosses, and obvious peripheral congestion and edema. In A2 period, there are necrosis of the ulcer surface with thinner coverage of the moss, and obvious peripheral congestion and edema.

2.

Healing stage can be subdivided into H1and H2 periods. In H1 period, there is no necrosis on the ulcer surface with thinner or absent coverage of the white moss, erosion, alleviated or absent peripheral congestion and edema, and regeneration of the epithelium. In H2 period, there are absent erosion, slight peripheral congestion or absent peripheral congestion and edema, obvious regeneration of epithelium and mild mucosal concentration.

3.

Scar stage can be subdivided into S1 and S2 periods. S1 period is also known as the red scar period, with red scar, no peripheral congestion and edema, regenerated epithelium and concentrated mucosa. In S2 period is also known as the white scar period, with white scar at the locations of ulcers and obvious concentrated mucosa.

Its staging can facilitate the description in the clinical diagnosis. However, the borderlines between stages and periods are difficult to be defined.

Case Study 1

A male patient aged 26 years was confirmatively diagnosed as having AIDS by the CDC. He had symptoms of epigastric pain for several months. His CD4 T cell count was 85/μl.

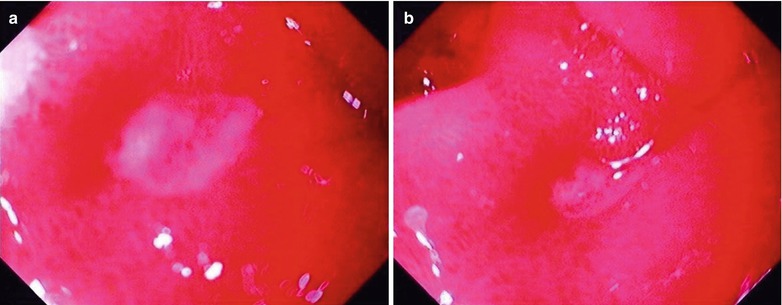

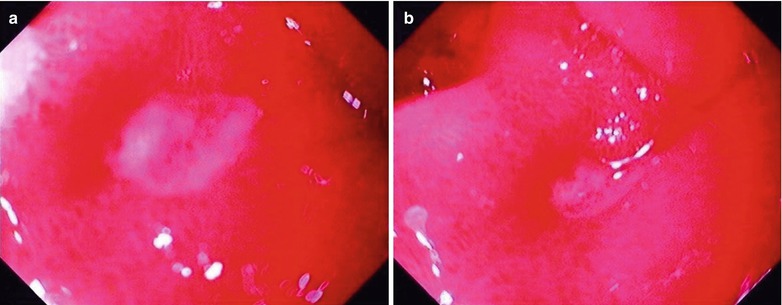

Fig. 19.13

(a–f) HIV/AIDS related chronic superficial gastritis, duodenal ulcer (A2), duodenal pseudodiverticulum. (a–d) Gastroscopy demonstrates slight congestion and edema of antral mucosa, deformed duodenal bulb, pseudodiverticulum of the anterior wall, swelling lesions in size of 2 × 3 cm in the posterior wall, quite smooth, ulcer in size of 0.5 cm in the inferior wall with coverage of white moss, and peripheral mucosal congestion and edema by gastroscopy. (e, f) The histopathological analysis demonstrates atrophic and loosened gastric interstitium, dilated gland lumen, infiltration of large quantity inflammatory cells, and severe inflammation

19.5.6 Criteria for the Diagnosis

1.

Clinical symptoms include acid reflux, chronic epigastric pain and other symptoms.

2.

By gastroscopy, there is mucosal erosion or ulceration of the stomach and duodenum.

3.

Digestive radiology demonstrates niche shadow of the duodenal bulb, gathered mucosa and irritation sign.

4.

Biopsy for pathology demonstrates infiltration of large quantity inflammatory cells.

19.5.7 Differential Diagnosis

1.

Various lesions of gastritis, functional gastrointestinal diseases.

2.

Benign ulcers and malignant ulcers.

3.

Gastric cancer, hepatobiliary tumor and pancreatic head carcinoma.

4.

Colonic irritation syndrome.

19.6 HIV/AIDS Related Ileocecal Tuberculosis

19.6.1 Pathogens and Pathogenesis

HIV/AIDS-related ileocecal tuberculosis generally is caused by the mycobacterium tuberculosis along with blood flow, and it can also be caused by drinking contaminated milk or dairy products. People with bovine tuberculosis can also spread the disease. Its spreading routes include (1) gastrointestinal infections are the main spreading routes of ileocecal tuberculosis. After the oral intake of mycobacterium tuberculosis, they cannot be killed by gastric acid due to its adipose enveloping membrane. When the bacteria reaches the ileocecus, the food containing mycobacterium tuberculosis has been chyme, which has a greater chance to directly contact with the intestinal mucosa. Simultaneously, due to the physiological retention and reverse peristalsis of the ileocecus, the chance of infection increases. In addition to the abundant lymphoid tissues in the ileocecus, its susceptibility to tuberculosis increases its chance of infection. Therefore, intestinal tuberculosis mostly occurs in the ileocecus. (2) Spreading along with blood flow is also an infection route of intestinal tuberculosis. HIV/AIDS related miliary tuberculosis invades the intestinal tract via spreading along with blood flow. (3) Intestinal tuberculosis can also be caused by the direct spread of intra-abdominal tuberculosis, such as fallopian tuberculosis, tuberculous peritonitis and mesenteric lymph nodes. And such infections are spread along with lymph flow.

19.6.2 Pathophysiological Basis

Ileocecus is a predispose site of HIV/AIDS related intestinal tuberculosis. It commonly occurs in young and middle aged populations, with female patients slightly more than male patients. After invasion of TB bacteria, its pathological changes vary with the immunity and allergic responses to mycobacterium tuberculosis. In the cases of large quantity bacteria invasion with high toxicity, and strong allergic reactions of human body, the lesions are commonly exudative, possibly with caseous necrosis and ulceration. In the cases of mild infection but strong immunity (mainly cellular immunity) of the human body, the lesions are often hyperplastic, with tuberculous nodules and further fibrosis, known as hyperplastic intestinal tuberculosis. Mixed intestinal tuberculosis sometimes occurs.

19.6.2.1 Ulcerative Intestinal Tuberculosis

After invasion of mycobacterium tuberculosis to the intestinal wall, firstly the concentrated lymphoid tissue in the intestinal wall causes congestion, edema and exudative lesions, which further develop into caseous necrosis. After that, ulceration occurs to spread peripherally. The borders of the ulcers may be irregular with different depth, sometimes to the muscular layer or serosa layer of the intestinal wall, and even involve the peritoneum or adjacent mesenteric lymph nodes. Ulcers of intestinal tuberculosis can spread with lymph flow of the intestinal wall, mostly in ring shape. Ulcerative intestinal tuberculosis is often demonstrated as having adhesion with abenteric tissues, and therefore low incidence of intestinal perforation. In the repairing process, due to large quantity fibrous tissue hyperplasia and scar formation, ring shaped stenosis of intestinal lumen can occur.

19.6.2.2 Hyperplastic Intestinal Tuberculosis

In the early stage, there are local edema and lymphangiectasia. In the chronic period, there are hyperplasia of large quantity tuberculous granulation tissue and fibrous tissue, commonly in the inferior layer of mucosa with nodules of varying sizes. In the serious cases, there are tumor liked masses protruding into the intestinal lumen to cause intestinal stenosis, and even intestinal obstruction.

19.6.3 Clinical Symptoms and Signs

Most patients have a history of pulmonary tuberculosis, with symptoms of the lower right abdominal pain. By palpation, there are restricted tenderness point and abdominal mass of medium hardness, possibly with slight tenderness and limited mobility. Ulcerative intestinal tuberculosis is often accompanied by tuberculosis toxemia, with symptoms of low fever after noon, irregular fever, remittent/continued fever, accompanied by night sweating as well as fatigue, emaciation, anemia and malnutritional edema and other symptoms and signs.

19.6.4 Examinations and Their Selection

19.6.4.1 Tuberculin Test

The finding is an important indicator for the definitive diagnosis.

19.6.4.2 Hemogram Erythrocyte Sedimentation Rate

The cases of ulcers commonly have normal or lower WBC count, higher lymphocyte count, with signs of slight and moderate anemia. In patients in active phase of TB, the erythrocyte sedimentation is often accelerated.

19.6.4.3 Stool Examination

In cases of hyperplastic intestinal tuberculosis, the stool has no significant changes. In cases of ulcerative intestinal tuberculosis, microscopic examination of the stool demonstrates small quantity of pyocytes and erythrocytes.

19.6.4.4 Colon Endoscopy

It can be applied for the direct observation of ileocecal lesions. And it can also be used for the collection of specimens for biopsy and bacteria culture.

19.6.4.5 Diagnostic Imaging

Barium meal radiography or barium enema examination is of great significance for the diagnosis of intestinal tuberculosis. Patients with complication of intestinal obstruction should avoid barium enema, otherwise, barium enema can aggravate the obstruction.

19.6.5 Imaging Demonstrations

19.6.5.1 Digestive Radiology

(1) Leaping sign or irritation sign, accelerated intestinal movements, poor local adhesion of barium; (2) Thickened and deranged intestinal mucosal folds, with sawtooth liked borders and small niche shadow; (3) multiple polypoid hyperplasia; (4) thickened intestinal wall, irregular stenosis of intestinal lumen or perforation and adhesion.

19.6.5.2 CT Scanning

It demonstrates edema and thickening of the intestinal wall, irregular stenosis of intestinal lumen or perforation and adhesion.

19.6.5.3 Gastroscopy

It can be applied for the direct observation of the lesions in the entire colon, the cecum and ileocecus. It can also be used for the collection of specimens for biopsy and bacteria culture to find the mycobacterium tuberculosis.

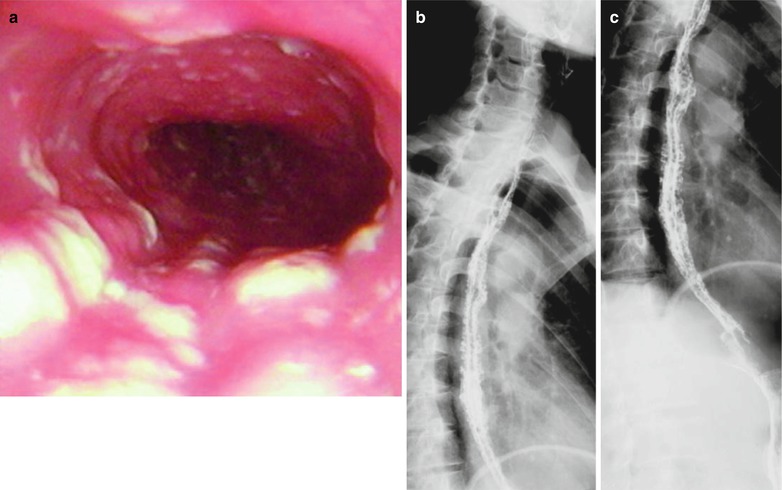

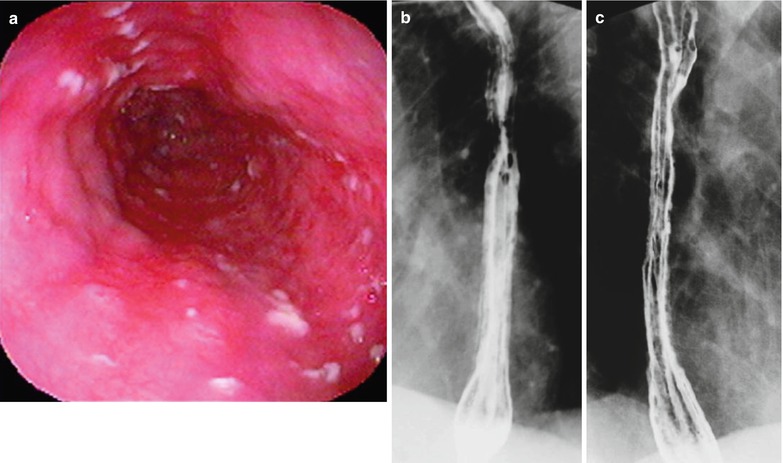

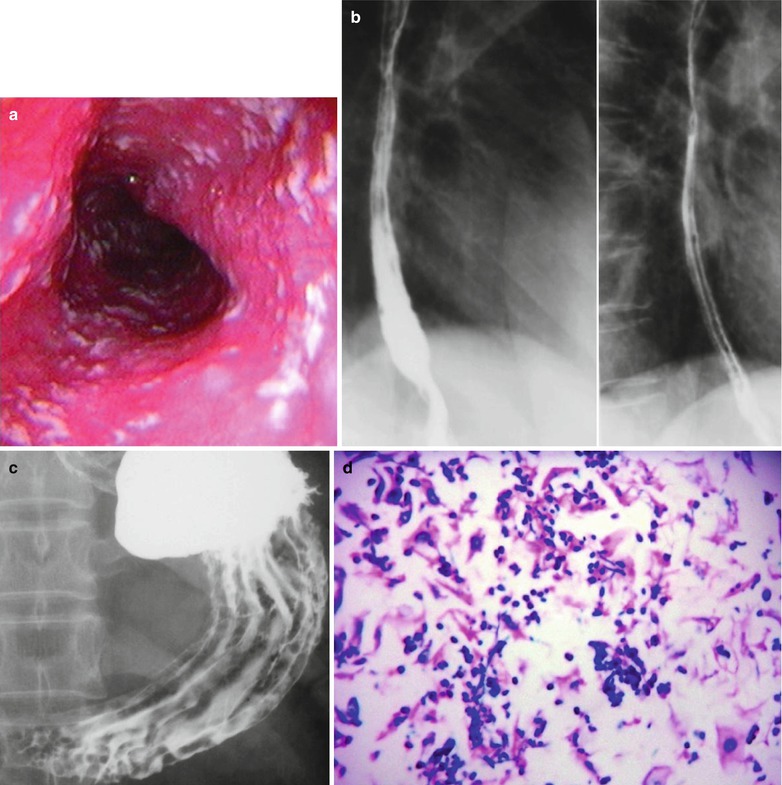

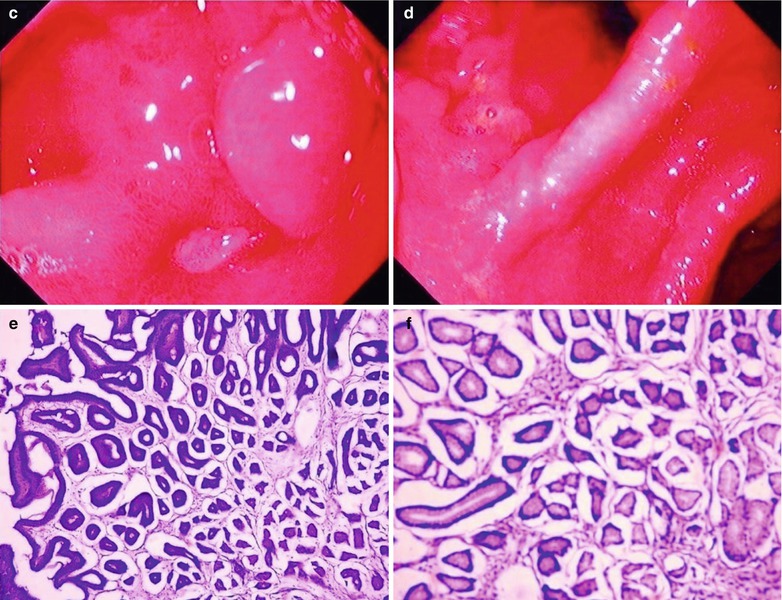

Case Study 1

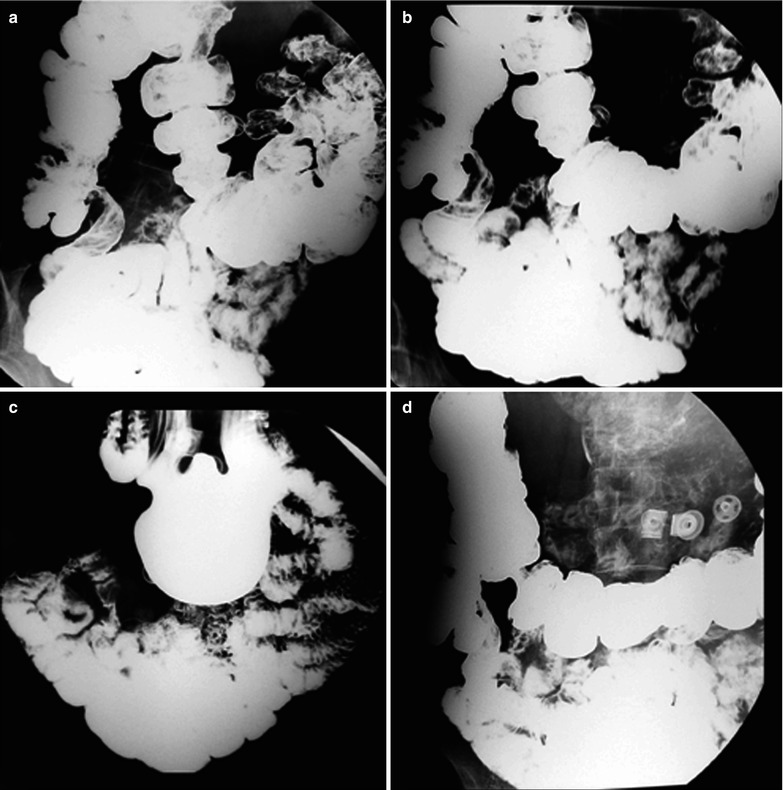

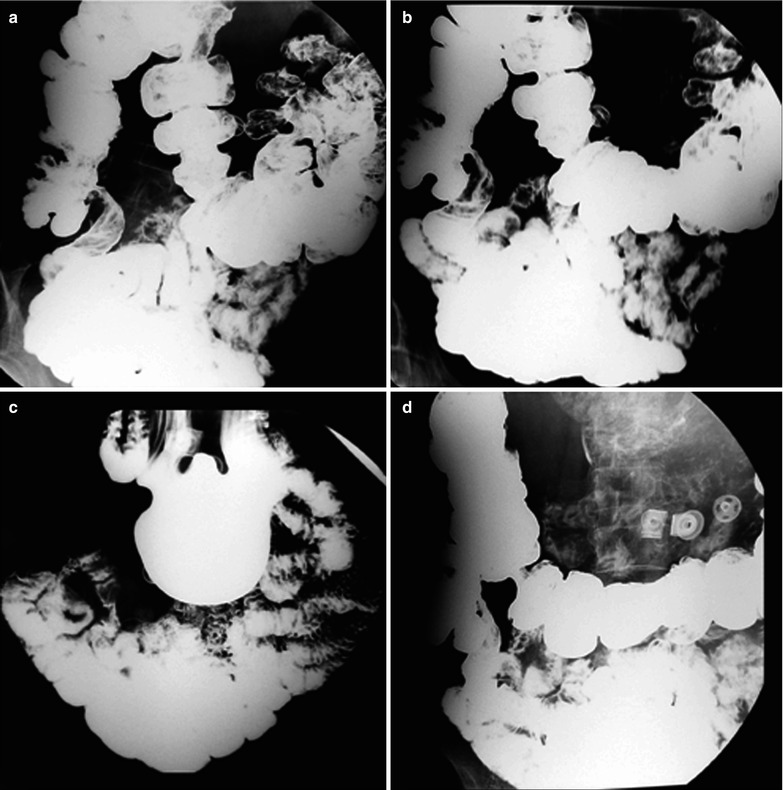

A female patient aged 53 years was confirmatively diagnosed as having AIDS by CDC. She had a history of paid blood donation and had been HIV positive for 5 years. She complained of fatigue and night sweat for 2 months, intermittent fever for 1 month, with right lower abdominal pain. Her CD4 T cell count was 85/μl.

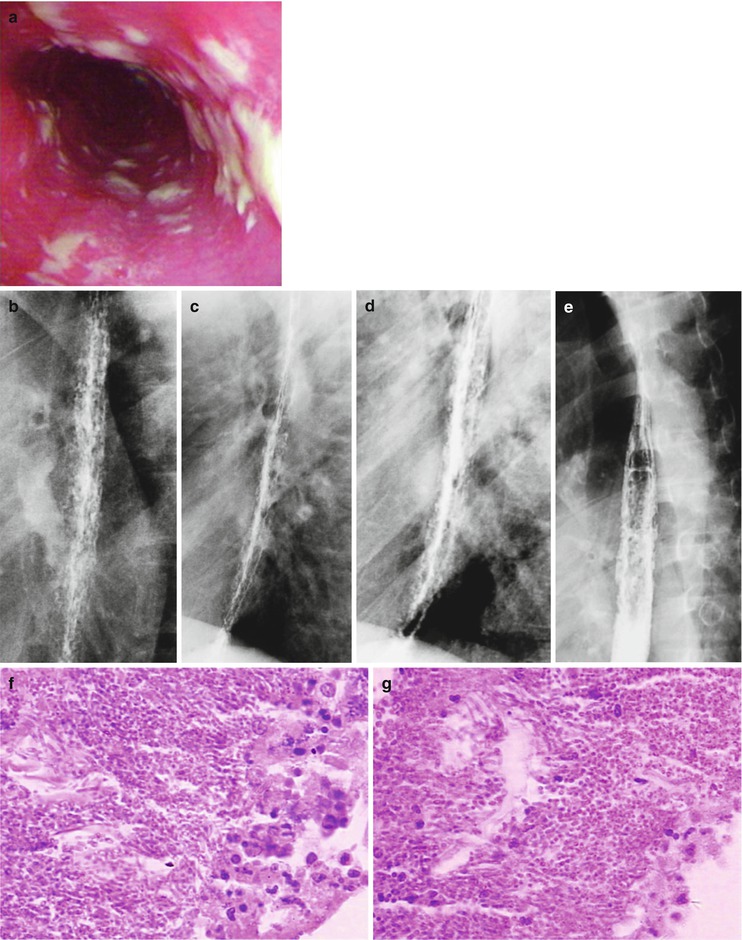

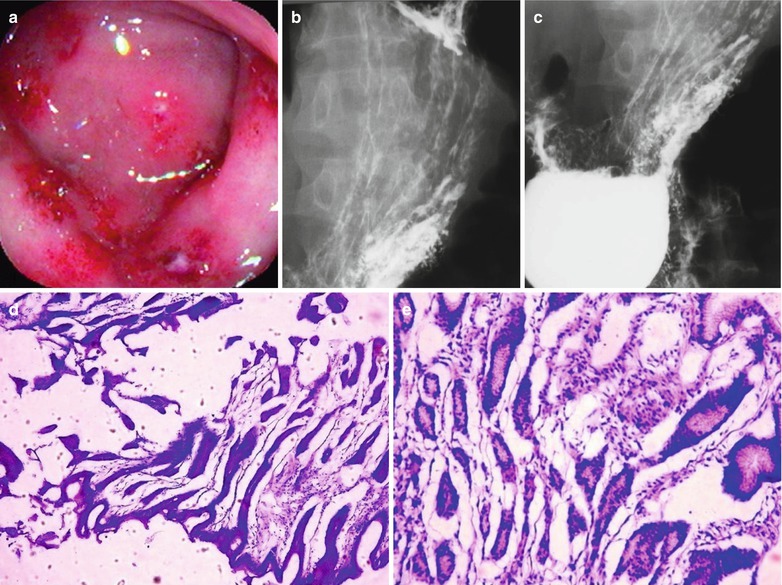

Fig. 19.14

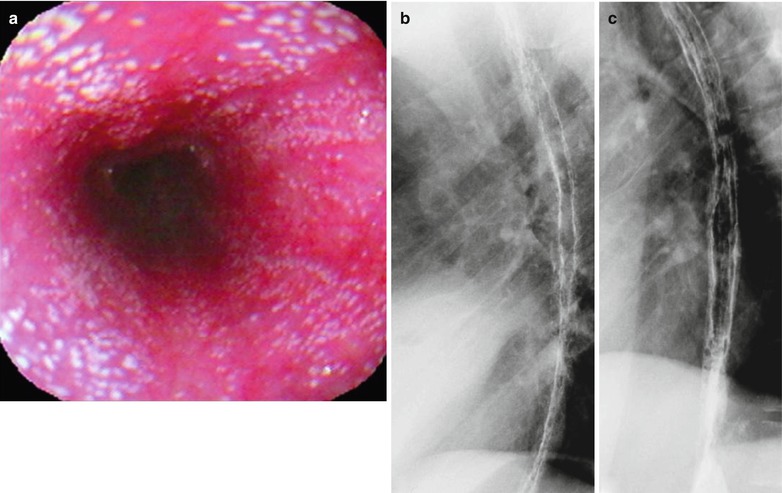

(a–d) HIV/AIDS related ileocecal tuberculosis. (a–d) Barium meal radiography demonstrates right ileocecal stenosis, poor filling, irregular intestinal wall and fine ulcers

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree