(1)

Radiology Department Beijing You’an Hospital, Capital Medical University, Beijing, People’s Republic of China

20.1.1 Hepatic Diseases

20.1.3 Splenic Diseases

20.1.4 Pancreatic Diseases

20.2.1 HIV/AIDS Related Lymphoma

20.3.5 HIV/AIDS Related Cirrhosis

20.5.1 Pathogens and Pathogenesis

20.5.2 Pathophysiological Basis

20.5.3 Clinical Symptoms and Signs

20.5.5 Imaging Demonstrations

20.5.6 Diagnostic Basis

20.5.7 Differential Diagnosis

20.7.1 Pathogens and Pathogenesis

20.7.2 Pathophysiological Basis

20.7.3 Clinical Symptoms and Signs

20.7.5 Imaging Demonstrations

20.7.6 Diagnostic Basis

20.7.7 Differential Diagnosis

20.8.1 Discussion

Abstract

The liver, gallbladder, pancreas and spleen are the commonly involved organs in AIDS patients and it has been reported that 60–84 % AIDS patients have hepatomegaly and hepatic dysfunction, with accompanying jaundice and 60 % AIDS patients have increased aminotransferase and serum alkaline phosphatase.

20.1 General Introduction to HIV/AIDS Related Hepatobiliary, Pancreatic and Splenic Diseases

The liver, gallbladder, pancreas and spleen are the commonly involved organs in AIDS patients and it has been reported that 60–84 % AIDS patients have hepatomegaly and hepatic dysfunction, with accompanying jaundice and 60 % AIDS patients have increased aminotransferase and serum alkaline phosphatase.

20.1.1 Hepatic Diseases

The opportunistic infections of the liver are due to cellular immunodeficiency, and some opportunistic infections can suppress the immune functions.

(1) CMV infection. It is common and often disseminated. In the hepatic parenchyma, there are diffuse microabscesses but no diffuse fused necrotic foci. (2) Mycobacteria infection. The incidence of mycobacteria infection is about 46–57 % in AIDS patients, mostly of M. avum complex (MAC) infection. Abdominal CT scanning or US examination demonstrates focal lesions in the liver parenchyma, with characteristic changes of granulomatosis formation with histocyte proliferation and sometimes abscesses formation. (3) Parasitic infection. Toxoplasma infection can result in degeneration and necrosis of hepatic cells, lymphocytes infiltration and formation of granuloma. Leishmania infection can also spread to the liver. AIDS complicated by Leishmania infection has a high morbidity. (4) Fungal infection. It usually leads to hepatomegaly and hepatic granuloma. Candida infection with accompanying microabscess in the liver is occasionally reported. (5) Carinii infection. Pneumocystis carinii pneumonia is an important diagnostic indicator of AIDS. Moreover, Carinii can involve extra-pulmonary tissues such as esophagus, gastrointestine, liver and spleen, and kidney, about 35 % with hepatic lesions. The diagnostic imaging demonstrates diffuse nodules in the liver, spleen and kidney, often accompanied by dystrophic calcification. (6) Bacterial infection. It is relatively rare. (7) Hepatic tumor. The most common hepatic tumor is KS, followed by non-Hodgkin’s lymphoma (NHL). About 30 % male homosexual AIDS patients have initial clinical manifestations of KS. CT scanning or liver scintigraphy demonstrates KS as multiple intrahepatic nodules which are non-specific changes. Moon et al. reported 19 % KS is demonstrated as hepatomegaly and only 3 % with focal lesions by abdominal CT scanning [12]. The incidence of HIV/AIDS related NHL is 6–8 %, with clinical manifestation of hepatomegaly. Abdominal imaging demonstrates intrahepatic focal lesions. (8) HIV/AIDS related hepatic hemangioma. AIDS complicated by hemangioma is not necessarily related to HIV infection but may be accompanying lesions. Trojan et al. reported its incidence of about 3 % [17].

20.1.2 Gallbladder and Biliary Diseases

Gallbladder and biliary diseases can also occur in AIDS patients, usually manifested as acalculous cholecystitis and AIDS cholangiopathy. CT scanning and MR imaging demonstrate thickened and coarse gallbladder wall. Recent studies have demonstrated that parasitization of Cryptosporidium on biliary epithelium can cause cholangitis and cholecystitis, with an incidence of 10 % in AIDS patients. Its principal clinical symptoms include nausea, vomiting, and abdominal confined pain of the right upper quadrant. X-ray demonstrates sclerotic cholangitis signs such as thickened gallbladder wall, proximal cholangiectasis, distal biliary stenosis and irregular biliary lumen.

20.1.3 Splenic Diseases

AIDS can involve spleen throughout its progression. In the acute period of HIV infection, some patients have splenomegaly. In the AIDS associated syndrome period, spleen changes along with lymph nodes from primary proliferation to lymphopenia. In the typical AIDS period, malignant lymphoma can also involve the spleen.

20.1.4 Pancreatic Diseases

AIDS patients have 35–800 times risk for developing acute pancreatitis than the general population. In other words, about 5–14 % HIV-infected patients experience acute pancreatitis and pancreas swelling, which can be caused by drugs, immunodeficiency, opportunistic infections and alcohol abuse. Infiltration of pancreatic lymphoma and KS can lead to pancreatic duct obstruction, which would trigger pancreatitis. By autopsy, pancreatic lymphoma and KS have an incidence of about 8 % in AIDS patients but usually without clinical symptoms. After the occurrence of AIDS complicated by pancreatitis, the further complications of pancreatic pseudocyst, acute respiratory distress syndrome and multiple organs failure may also occur.

20.1.4.1 Imaging Demonstrations Review

CT scanning, MR imaging or US examination should be the diagnostic imaging of choice for the diagnosis of hepatic lesions or cholangiectasis. However, the diagnostic imaging demonstrates no abnormalities in AIDS patients with biliary disease, with failed detection of choledocholith. Endoscopic retrograde cholangiography can facilitate diagnose of highly suspected biliary disease. Patients with hepatic focal lesions, biopsy guided by CT scanning or US examination can provide valuable diagnostic information. Focal lesions are not necessarily malignancies. In AIDS patients, opportunistic infections are sometimes suspected as metastatic tumors while histological examinations demonstrate as curable diseases such as tuberculosis or Carinii infection.

20.2 HIV/AIDS Related Liver Tumor

20.2.1 HIV/AIDS Related Lymphoma

Non-Hodgkin lymphoma (NHL), HIV/AIDS related lymphoma, is following KS to be the second commonly malignancy in AIDS patients. HIV infected people are at a significantly higher risk of developing lymphoma, especially senior B-cell lymphomas occurring at a CD4 T cell count of less than 100/mm3. The proportion of extranodal lymphoma is higher than HIV negative patients. Meanwhile, the incidence of HIV/AIDS related hepatic NHL is 6–8 %.

20.2.1.1 Pathogens and Pathogenesis

The classical model of ARL occurrence is as the following. B lymphocytes, under the violent stimulations by HIV, Epstein Barr Virus (EBV) and other infectious agents, induce continuous release of growth factors and cytokines to increase the risk of genetic mutations in the proliferative cells groups which accelerates B cell malignancy. The commonly found mutated genes include proto-oncogene c-myc (found in Burkitt lymphoma), bcl-6 (found in diffuse large B-cell lymphoma) and some anti-oncogenes. Studies have demonstrated a constant relationship between the occurrence of EBV infection and some diffuse large B-cell lymphoma (DLBCL).

20.2.1.2 Pathophysiological Basis

ARL can be categorized into three types by naked eyes observation. (1) Singular nodule/mass. An isolated large nodule/mass in the liver, commonly with a diameter of above 3 mm. (2) Multiple nodules. Multiple small nodular foci in the liver, commonly in a diameter of less than 3 mm. (3) Diffuse infiltration or hepatomegaly. With unclearly defined foci and with no distinct nodules or masses.

Histologically, DLBCL and Burkitt lymphoma are the most common ARL, accounting for about 90 %. According to cellular origins, DLBCL can be divided into two subtypes: centroblast type (originated from B cell of germinal center) and immunoblast type (originated from B cell after germinal center)

20.2.1.3 Clinical Symptoms and Signs

The clinical manifestations include abdominal pain, abdominal distension, emaciation, fatigue, superficial lymphadenectasis as well as hepatomegaly and splenomegaly.

20.2.1.4 Examinations and Their Selection

US Examination, CT Scanning and MR Imaging

They have high detection rate of nodular and mass lymphoma but low detection rate of diffuse and infiltrative lesions.

PET

It can be applied to detect lymphoma or to screen residual foci of lymphoma.

Liver Biopsy

It is the primary basis for the definitive diagnosis.

20.2.1.5 Imaging Demonstrations

Ultrasound Examination

Singular nodule type or mass type is demonstrated as low echo, few even no echo. Sometimes, US demonstrates a target sign, namely central high echo of the focus and marginal low echo, with low echo infiltration shadow of the unclear tumor border. Multiple nodule type usually involves several organs, demonstrated as multi-focal low echo nodules. Diffuse infiltration type shows liquid or gel liked lesions between abdominal organs and mesentery. Although the lymphoma infiltration is parenchymal, there is almost no echo by US.

CT Scanning

For the singular nodule/mass type, plain CT scanning demonstrates singular or multiple masses or nodules with low density in the liver, mostly with clear boundary. The singular lesion may be lobular but the multiple lesions are round or oval. The large nodule commonly has central necrosis in much lower density, occasionally with calcification. Enhanced scanning demonstrates no enhancement or only light enhancement in the artery phase, whereas clearly defined focus in the vein phase, with no enhancement or merely slight even enhancement of the tumor. The focus has a lower density than liver parenchyma.

For the diffuse infiltration type, plain CT scanning demonstrates general decrease of liver density, with extended liver contour in disproportion. Enhanced scanning demonstrates no masses or nodules. Apicella et al. [1] believed that no matter which type the lesions are, the peripheral blood vessels have demonstrations of stenosis due to compression, migration due to push and pull, deformation, but mostly no invasive obstruction, interruption and destruction. Enhanced scanning demonstrates continuous blood vessels shadow in the peritumor tissues or in the tumor, which is the characteristic demonstration of the disease.

MR Imaging

For the nodule/mass type, T1WI demonstrates low signal foci in the liver parenchyma, with clear boundary, in round or lobular shape. T2WI demonstrates slightly higher to high signal, with clear boundary, with central much higher or no signal. For the diffuse infiltration type, T1WI demonstrates decreased liver signal in the liver while T2WI increased liver signal, including demonstrations of enlarged liver and disproportional liver, but with no findings of nodule/mass foci. Enhanced imaging demonstrates the same as CT scanning, with no obvious enhancement or slight marginal enhancements of the foci in arterial/venous phases. There are continuous blood vessels surrounding or in the tumors.

Case Study 1

A female patient aged 37 years was confirmatively diagnosed as having AIDS by CDC. She complained of fever for more than 1 month and fatigue for 1 week. She had a history of intravenous drug abuse, with physical examinations findings of LDH 1,787 U/L, AFP <50 U/L and enlarged liver. Her CD4 T cell count was 85/μl.

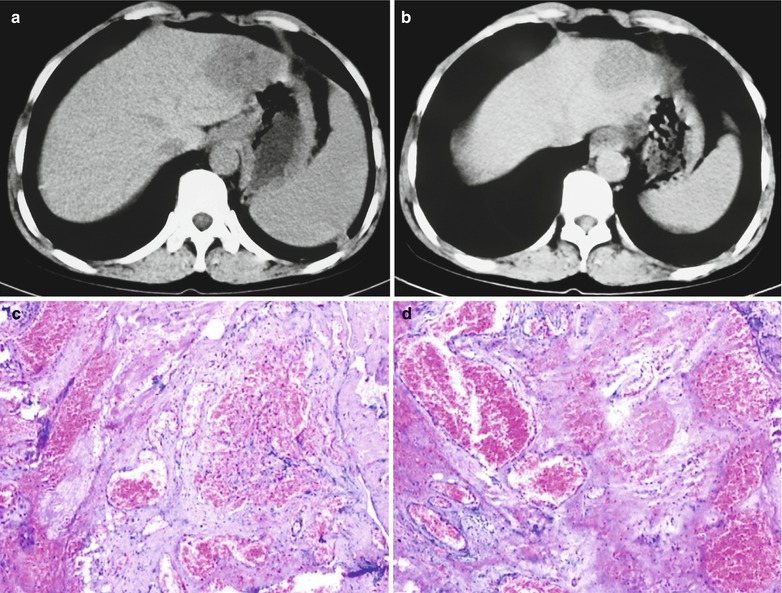

Fig. 20.1

(a, b) HIV/AIDS related hepatic lymphoma. (a) CT scanning demonstrates enlarged liver with regular border. Plain scanning demonstrates uneven density in the liver parenchyma. Enhanced scanning demonstrates diffuse nodular low density shadows of various sizes at the arterial phase in the liver parenchyma, with clear borders. In addition, there are fusion of some foci with marginal uneven ring shaped enhancement, low density foci at the portal and delayed phases. (b) HE staining demonstrates hepatic T cell lymphoma, with diffuse distribution of the tumor cells in the hepatic sinus. Immunohistochemistry findings of tumor cell CD3 positive demonstrated in the left upper corner and tumor cell CD45RO positive demonstrated in the right upper corner, HE ×100 (Figs provided by LANG, ZHW)

Case Study 2

A male patient aged 27 years was confirmatively diagnosed as having AIDS by CDC. He found a cervical mass that was progressively enlarging for 5 months, with no symptoms of fever and pain. He had a past history of intravenous drug abuse. On admission, he was found HIV antibody (+), CD4 T cell count 420/μl. By physical examination, multiple lymphadenectasis in the left side of neck, hard, poor mobility, with multiple foci fusion into a mass in size of 4 × 5 cm.

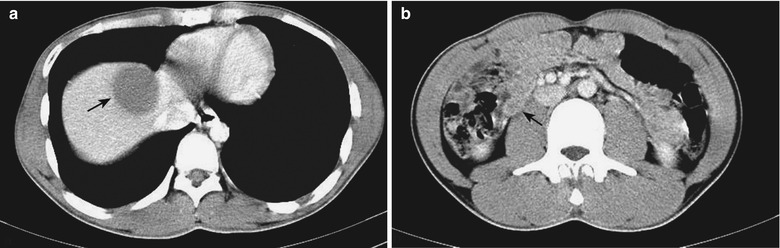

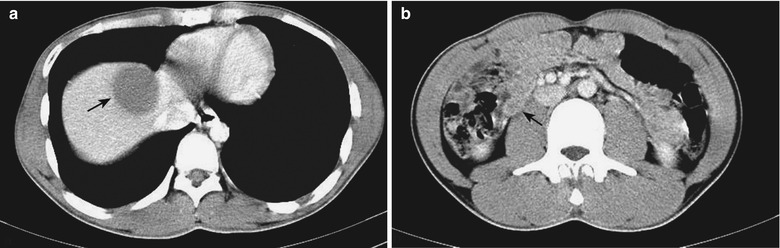

Fig. 20.2

(a–f) HIV/AIDS related hepatic lymphoma. (a) CT scanning demonstrates round liked low density shadow in the right hepatic lobe, in size of 4.0 × 3.5 × 2.4 cm, with homogeneous density and a CT value of about 47 HU. Enhanced scanning demonstrates slight enhancement of the foci at the arterial and portal vein phases, with clear boundary and a CT value of about 55 HU. (b) CT scanning demonstrates retroperitoneal multiple lymphadenectasis. (c, d) Cervical lymph nodes puncture for biopsy demonstrates pathologically and immunohistochemical confirmed diffuse giant B cell lymphoma. (e, f) Immunohistochemistry demonstrates CD20 (+) and CD79a (+)

20.2.1.6 Evidence for the Diagnosis

Imaging demonstrations of hepatic lymphoma are non-specific, whose accurate diagnosis should be made in combination with clinical data. The diffuse infiltration type can be misdiagnosed by CT scanning or MR imaging, which should be paid enough attention. Nodular hepatic lymphoma is demonstrated as multiple low density foci in the liver, with a tendency to fuse and no/slight enhancement by enhanced imaging.

20.2.1.7 Differential Diagnosis

Diffuse Hepatic Cancer

Diffuse infiltration hepatic lymphoma should be differentiated from diffuse hepatic cancer. The former merely results in thinner vein due to compression but with no involvements of the vascular wall and cavity, while the latter is prone to cause portal vein embolus and coarse venous wall in the liver. In addition, diffuse hepatic cancer has the foci of relatively even density while diffuse infiltration hepatic lymphoma has the foci of uneven density.

Hepatic Metastatic Tumor and Nodular Hepatocellular Carcinoma

The imaging demonstrations of nodular hepatic lymphoma are quite similar to those of hepatic metastases and nodular hepatocellular carcinoma. For primary hepatic lymphoma, extrahepatic organs and tissues generally present no changes. Delayed scanning of hepatic lymphoma in the arterial and port vein phases shows no obvious enhancement, with relatively even density and rare necrosis in the foci, which is different from the enhancement features of hepatic cancer and metastases. Occasionally, biopsy should be performed to differentiate hepatic lymphoma from hepatic metastases and nodular hepatocellular carcinoma.

20.2.2 HIV/AIDS Related Kaposi Sarcoma (KS)

Kaposi sarcoma is an indicative disease of AIDS, being commonly multiple and terminally involving the liver with an incidence of 14–18 %. KS is the most common hepatic malignant tumors in AIDS patients and is the most common reason of death in AIDS patients.

20.2.2.1 Pathogens and Pathogenesis

Until now, the pathogen of KS has not been fully unveiled. It is presumed to be associated with viral infections, heredity factors and hormones, among which viral infection, particularly KS associated virus (KSHV) infection is assumed to be a necessary factor for the occurrence of KS. KSHV genes encodes are similar to many cytokine analogues which make cellular growth independent of host regulation, thus increasing the possibility of tumors formation. HIV infection is an essential cofactor for the occurrence of KS, which impairs the defense mechanism of the hosts to facilitate KSHV replication. Moreover, some experts believe that EBV, CMV and HIV are all helper viruses that contribute to the occurrence of KSHV infection.

20.2.2.2 Pathophysiological Basis

By naked eyes observation, there are dark red tumor nodules in diameter of 5–10 mm on the liver envelope, radial growth of KS in the portal area and its infiltration along the biliary branches on the cross sections. Multiple dark red spots can be found in the liver parenchyma. Histologically, the typical pathological changes include infiltration of the tumor into portal area, enlarged portal area, focal concentration of large quantity hyperplasia of the vascular vessels in angioma liked changes or vascular fracture. The foci also show hemorrhage, hemosiderin sedimentation and infiltration of lymphocytes and plasmacytes. Meanwhile acidophilic inclusion bodies can be found in the tumor cytoplasm.

20.2.2.3 Clinical Symptoms and Signs

Its clinical manifestations are non-specific, generally with liver involvement as a part of skin and organs diffuse lesions. The clinical manifestations are fever, emaciation, anemia and increased serum alkaline phosphatase.

20.2.2.4 Examinations and Their Selection

1.

Laboratory tests demonstrate slightly increased serum alkaline phosphatase.

2.

Ultrasound, CT scanning and MR imaging are commonly used diagnostic imaging, with non-specific demonstrations of KS.

20.2.2.5 Imaging Demonstrations

Ultrasound

Disseminated KS can involve almost all parts of human body. However, abdominal ultrasound rarely detects lesions in the liver, spleen and pancreas, because its involvement in the advanced stage of KS and KS grows in infiltration along portal vessels rather than mass growth. By ultrasound, the only finding is low echo changes at the marginal hepatic artery, portal vein and bile duct, namely the portal triad, while abnormal high echo of intrahepatic multiple nodules (5–12 mm) is rarely found. In the cases of skin or gastrointestinal KS, the following ultrasound signs can indicate the intrahepatic KS. (1) hepatic pedicle infiltration; (2) high echo foci in the liver parenchyma; (3) intrahepatic bile duct dilation but no extrahepatic bile duct dilation. The high echo area in the liver may be consistent with the spreading of KS.

CT Scanning

The demonstrations are multiple low density small nodules foci, with a distribution tendency of adjacent to hepatic portal, liver envelope and surrounding the perihepatic portal vein. There is also irregular enlargement of the portal vein branches shadows in the liver parenchyma. Enhanced scanning demonstrates multiple low density small nodules foci surrounding the hepatic portal, liver envelope and perihepatic portal vein in the early stage, with more amount than plain scanning. Delayed scanning for 4–7 min demonstrates enhancement of most nodular shadows, with equal or slightly higher density. Sometimes, the small nodules shadows are in ring shaped enhancement. In some cases, there are accompanying splenomegaly, lymphadenectasis of retroperitoneum, mesentery and peripancreas and high density of the involved lymph nodes.

MR Imaging

The demonstrations include high signal by PDWI, and high signal tumor focus with perivascular infiltration in a shape of grape cluster.

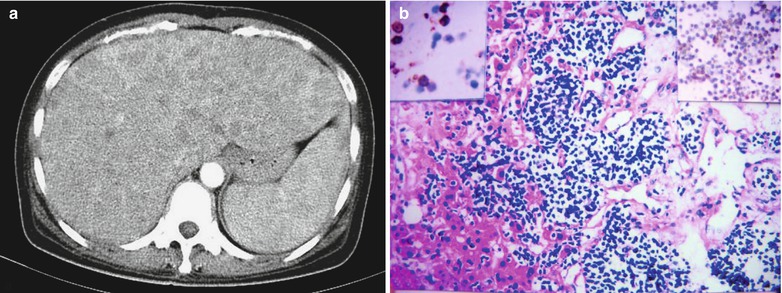

Case Study 1

A male patient aged 33 years was confirmatively diagnosed as having AIDS by CDC. He was found HIV antibody (+) 5 months ago, with present symptoms of cough, expectoration, nausea and diarrhea for 10 days. By physical examination, he was found to have emaciation, palpable enlarged hard lymph nodes without tenderness behind ears and at the bilateral groins, in size of about 10 × 20 mm. His CD4 T cell count was 87/μl.

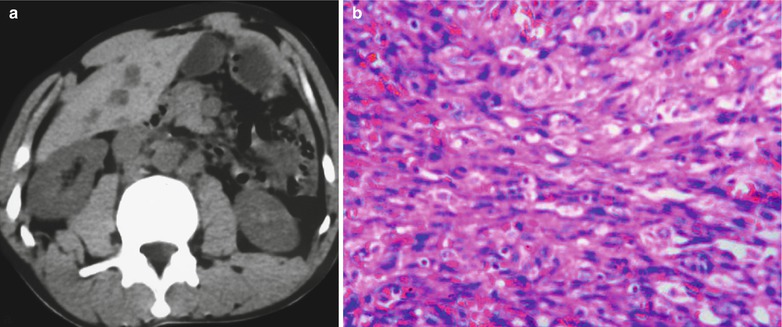

Fig. 20.3

(a, b) HIV/AIDS related KS carcinoma. (a) CT scanning demonstrates multiple low density nodular foci in the liver, multiple low density foci of various sizes in the abdominal cavity, with clear boundaries. (b) Biopsy demonstrates groin lymph nodes with abundant blood vessels like fissures and obvious proliferation of spindle cells

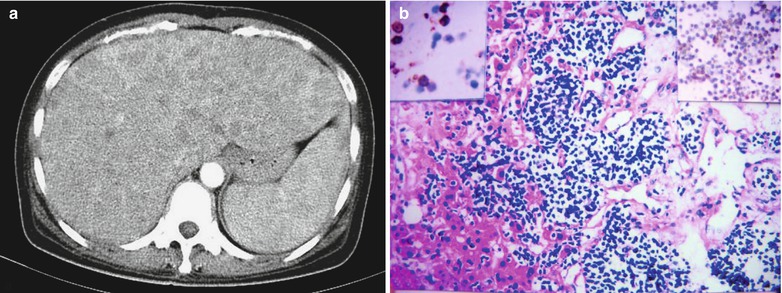

Case Study 2

A male patient aged 43 years was confirmatively diagnosed as having AIDS by CDC. His CD4 T cell count was 77/μl.

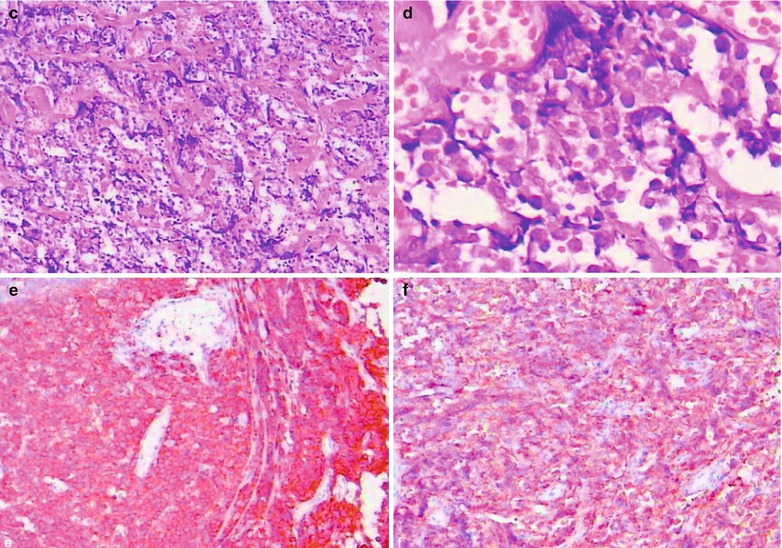

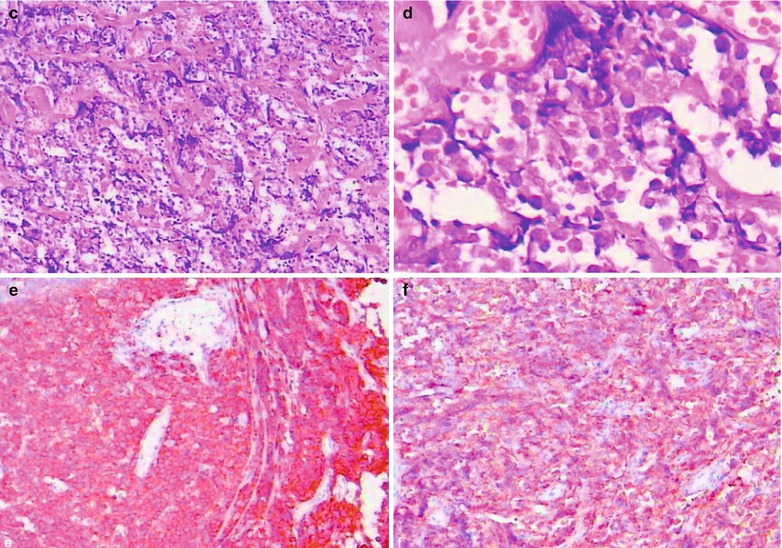

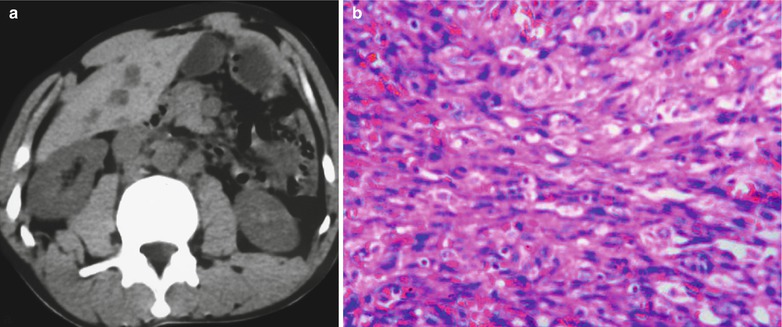

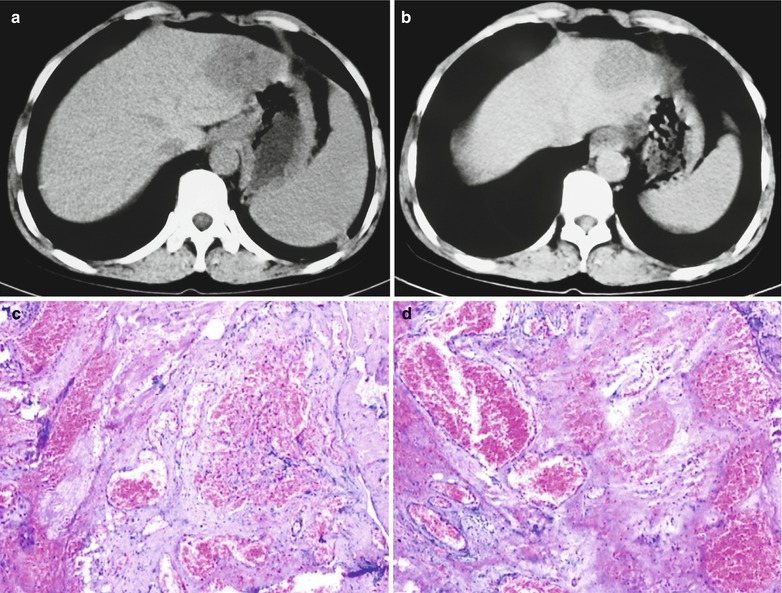

Fig. 20.4

(a, b) HIV/AIDS related Kaposi carcinoma. CT scanning demonstrates enlarged liver and spleen, multiple round low density foci of various sizes in the liver, with clear boundaries

20.2.2.6 Diagnostic Basis

Hepatic KS has no characteristic demonstrations by diagnostic imaging. The findings of hepatomegaly and multiple low density nodules in the liver with a distribution tendency around the portal area, liver envelope and peripheral portal veins, the clinical data indicates patients of HIV, organ transplantation or extremely compromised immunity. Especially in the cases with accompanying typical skin lesions (skin nodules and infiltrative spots in a bilaterally symmetric development in purplish brown or reddish blue with accompanying edema) and multiple organs lesions, the diagnosis of KS should be considered.

20.2.2.7 Differential Diagnosis

Hepatic Metastases

Both hepatic KS and hepatic metastases exhibit multiple nodular lesions. However, the lesions of KS are close to the portal area, liver envelope and perihepatic portal veins. Enhanced and delayed scanning demonstrate the lesions of KS as higher or equal enhancement comparing to the liver parenchyma, with rarely peripheral enhancement. The clinical data indicates compromised immunity and accompanying characteristic skin lesions. The lesions of hepatic metastases are scattered in the liver with similar sizes. The enhanced scanning demonstrates the foci mostly in marginal enhancement which is generally lower than normal liver parenchyma. In addition, the cases of hepatic metastases should have a past history of primary tumors.

Hepatic Lymphoma

Nodular hepatic lymphoma is demonstrated to have multiple low density foci in the liver with a fusion tendency. Enhanced scanning demonstrates no enhancement or slight enhancement. It is relatively difficult to be differentiated from KS. In combination with clinical manifestations and case history, the differential diagnosis can be made. The final definitive diagnosis depends on the biopsy.

Hepatic Schistosomiasis

Hepatic schistosomiasis shows subcapsular fibrosis and peripheral fibrosis of the portal vein. By the diagnostic imaging, it is similar to the distribution of KS nodules adjacent to the liver envelope and portal vein. However, hepatic schistosomiasis has characteristic envelope and septal calcification, resulting in map liked changes of the liver parenchyma. Meanwhile, the liver envelope and the septum are enhanced but no enhancement of the fibrosis foci by enhanced and delayed scanning, which are different from the findings of hepatic KS. In addition, the cases of KS commonly have impaired immunity, with accompanying characteristic skin lesions, while hepatic schistosomiasis usually has manifestations of hepatocirrhosis.

20.2.3 HIV/AIDS Related Hepatic Hemangioma

Hepatic hemangioma is the most common hepatic benign tumors, with an incidence of 0.4–7.3 % by autopsy. The diseases can be found in all age groups, but mostly in the middle aged females, with an incidence six times as high as that of males. About 90 % tumors are singular and the other 10 %, multiple. It occurs mostly below the liver envelope near the diaphragmatic surface, with involvement of both right and left liver lobes, but more in the right lobe. Hepatic hemangioma in AIDS patients may not necessarily be related to HIV infection but may be an accompanying lesion.

20.2.3.1 Pathogens and Pathogenesis

The cause of hepatic hemangioma remains unclear. Some scholars believe that it is caused by abnormal development of hepatic blood vessel structures and some other scholars believe that it is related to estrogen level.

20.2.3.2 Pathophysiological Basis

Histologically, hepatic hemangioma can be divided into cavernous hemangioma, sclerotic hemangioma, hemangioendothelioma and capillary hemangioma. Cavernous hemangioma is the most commonly seen in clinical practice.

Cavernous Hemangioma

By naked eyes observation, cavernous hemangioma is in blue or purplish red nodules with clear boundaries, mostly without capsules. Its cross section is honeycomb liked, with fibrosis, calcification and thrombus. Microscopy demonstrates tumors with components of vascular lumens and connective tissues of various sizes. The inner surfaces of the vascular lumens are covered by a single layer of flat endothelial cells.

Sclerotic Hemangioma

The tumor body is completely or mostly occupied by fibrous scar tissues or organized thrombus, usually with accompanying calcification. Lesions usually are small, with a diameter of less than 4 cm.

Hemangioendothelioma

The proliferation of vascular endothelial cells is active, which can readily cause malignant degeneration.

Capillary Hemangioma

It presents vascular stenosis and increased fibrous septal tissues.

20.2.3.3 Clinical Symptoms and Signs

Patients with hepatic hemangiomas in diameter less than 4 cm are usually asymptomatic, usually discovered occasionally in physical examination. About 40 % patients with hepatic hemangiomas in diameter more than 4 cm have abdominal irritation, hepatomegaly, poor appetite and indigestion. Huge hemangiomas can lead to significant enlargement of the liver and their rarely seen syndrome includes consumptive coagulation defect, thrombocytopenia and hypo-fibremia.

20.2.3.4 Examinations and Their Selection

CT Examination

It is an effective diagnostic imaging for the diagnosis and differential diagnosis of hepatic hemangioma.

MRI Examination

It can be applied for the diagnosis and differential diagnosis of hepatic hemangioma, with higher sensitivity and specificity than CT scanning. It can define the diagnosis without enhanced imaging.

Ultrasound

It is commonly used for screening and following up. For some cases of cavernous hemangioma, it can be performed for the qualitative diagnosis.

20.2.3.5 Imaging Demonstrations

Ultrasound

The tumors are round or round liked masses, with clear boundaries. On its margin, there are fracture sign, vascular accessing or penetrating sign. Tumors are commonly demonstrated as strong echo and rarely weak echo or uneven mixed echoes. For the cases of huge tumors, the pressing to the tumor by the probe during scanning may show deformation of the tumor.

CT Scanning

Plain scanning demonstrates mostly round or round liked low density foci with some few foci in lobular appearance with even inner density. In the comparatively larger tumors, there are commonly complications of high density calcification or low density degeneration and necrosis. In the cases with complicated hepatic adipose infiltration, the foci show slight high or high density. Tumors are clearly defined from their surrounding normal hepatic tissues, without peritumor edema. Dynamic enhanced scanning demonstrates the following four types of enhancement of the hemangioma. (1) Even enhancement of the tumor at the arterial phase, with an enhancement degree close to the aortic artery density, and a higher enhancement of the tumor than the liver parenchyma density at both the portal and delayed phases. This type of enhancement is usually found in the cases of hemangioma with a diameter less than 1.5 cm. (2) C or flower ring shaped, or nodular enhancement at the peripheral area of the tumor at the arterial phase, or a marginal spot liked enhancement (with varying shapes due to different perspectives sections) that is similar to the aortic artery density. Subsequently, along with the contrast agent spreading gradually toward the center, the tumor is completely filled at the delayed phase to demonstrate high or equal density, with findings of central necrosis and no enhancement of the scar tissues. Such findings are found in the cases of hemangioma with a diameter of above 3 cm. These are typical enhancement demonstrations of hemangioma and are the most common demonstrations. (3) No enhancement at the arterial phase and peritumor nodular enhancement at portal or delayed phase. The tumor is slowly filled by the contrast agent, with long term duration up to 10 min. (4) No enhancement of the tumor by dynamic scanning at the arterial phase. This type of demonstration is extremely rare and commonly found in the cases of sclerotic hemangioma.

MR Imaging

Low or equal signal of the tumor is demonstrated by T1WI; bright high signal by T2WI, which is highly similar to the demonstrations of hepatic cysts. However, hemangioma presents a higher T2 signal, in characteristic bulb sign. With the prolonging of TE, the signal of the tumor gradually increases in intensity, in contrast with the low signal of the liver parenchyma. Under the condition of TE 120–180 ms, hemangioma demonstrates similar signal to the cerebrospinal fluid. Hemangiomas with a diameter less than 3 cm have a homogenous signal while hemangiomas with a diameter above 3 cm show a heterogeneous signal in the tumor body. The central necrosis shows a higher signal than the peritumor tissues by T2WI. Fibrous scars always present low signal by both T1WI and T2WI.

The specificity of MR imaging to hemangiomas is up to 92–95 %. MR imaging can define the diagnosis without enhanced imaging. However, for some cases of atypical hemangioma or suspected with complications of other malignancies, dynamic enhanced imaging with Gd-DTPA can provide further information for differential diagnosis, with consistent enhancements with enhanced CT scanning. Degenerations, necrosis and thrombus in the tumors present no enhancement in low signal.

By enhanced imaging with SPIO, due to the contents of Kupffer cells in the hemangiomas, the foci are demonstrated low signal by T2WI, being still high comparing to that of the normal hepatic parenchyma.

Case Study 1

A female patient aged 43 years was confirmatively diagnosed as having AIDS by CDC. Her CD4 T cell count was 80/μl.

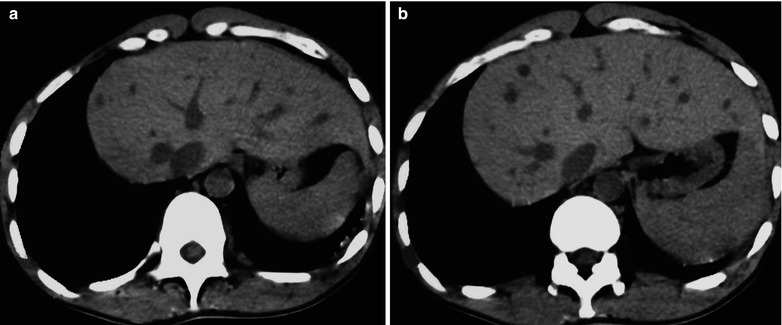

Fig. 20.5

(a–d) HIV/AIDS related hepatic hemangioma. (a, b) CT scanning demonstrates round low density foci in the lateral segment of the hepatic lobe, with clear boundaries. Enhanced scanning demonstrates even enhancement of the foci at the venous phase, with clear boundary and lower density than surrounding hepatic parenchyma. (c, d) HE staining demonstrates cystic enlarged space with accumulation of large quantity erythrocytes in it

Case Study 2

A male patient aged 29 years was confirmatively diagnosed as having AIDS by CDC. His CD4 T cell count was 117/μl.

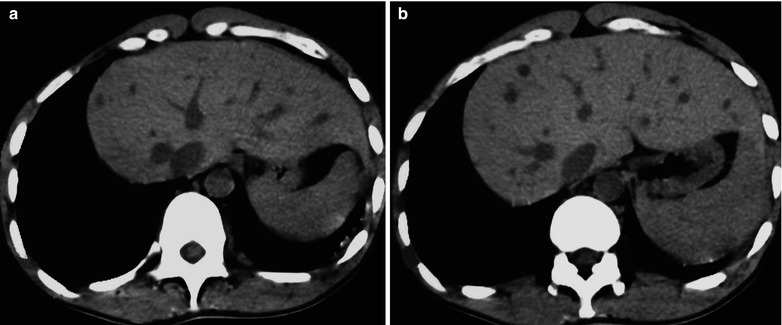

Fig. 20.6

HIV/AIDS related hepatic hemangioma. Enhanced CT scanning demonstrates round low density foci at the arterial phase under the envelope in the posterior segment of the right hepatic lobe, in size of 8 × 6 mm with clear boundaries, and marginal nodular enhancement of the foci

20.2.3.6 Criteria for the Diagnosis

CT scanning, MR imaging and ultrasound are all of great value for the diagnosis, with typical demonstrations of the hepatic tumors presenting less difficulties for the diagnosis. CT scanning can define the diagnosis of up to 90 % cases of cavernous hemangioma. For the cases with concurrent bulb sign by MR imaging; marginal fracture sign, vascular accessing or penetrating sign, the accuracy rate of diagnosis can be increased.

20.2.3.7 Differential Diagnosis

For hemangiomas with non-specific imaging demonstrations, it should be differentiated from other hepatic neoplastic lesions.

Primary Hepatocellular Carcinoma

Patients with primary hepatocellular carcinoma commonly have a history of hepatitis and hepatocirrhosis, AFP positive and peritumor edema, with involvement of adjacent portal veins and bile ducts. Its adjacent hepatic envelope shrinkage is more common. By MR imaging, weighted T2WI of hemangiomas presents bulb sign while hepatocellular carcinoma presents slightly high or equal signal. By enhanced imaging, hemangioma manifests enhancement of “early in and late out” or “late in and late out” while hepatocellular carcinoma presents “early in and early out” sign. In addition, hepatic carcinoma has pseudocapsule but hepatic hemangioma has no capsule. Especially by enhanced imaging at the delayed phase, the pseudocapsule of the hepatocellular carcinoma can be well defined.

Hepatic Metastases

Metastatic foci with abundant blood supply like nasopharyngeal carcinoma, leiomyosarcoma, carcinoid and neuroendocrine tumors have similar signal to hemangioma by T2WI. And the metastatic foci are demonstrated as low density by CT scanning. All these demonstrations present difficulty for their differential diagnosis. Enhanced scanning of these foci demonstrates even or uneven enhancement at the arterial phase, equal or slight low density of the decreased enhancement at the portal vein phase, which is obviously different from demonstrations of hemangioma, including nodular enhancement, slow filling and persistent enhancement. In addition, small liquefaction and necrosis foci in the tumor nodules are also facilitative for their differential diagnosis. Hepatic metastases are usually multiple. The case history and relevant laboratory tests findings can also be referred for the differential diagnosis.

Focal Nodular Hyperplasia (FNH)

Plain CT scanning demonstrates poorly defined slightly low density shadows. Dynamic enhanced scanning demonstrates obvious enhancement at the arterial phase, with slightly high or equal density signal. Delayed scanning demonstrates equal or slightly low signal. These demonstrations should be differentiated from hemangioma. The key points for the differential diagnosis are the enhancements by enhanced scanning: (1) Hepatic hemangioma usually presents nodular or cotton wool liked enhancement starting from the focus border toward the center, while FNH presents enhancement of the foci starting from the center towards the peripheral area like a spring or at the arterial phase presents a gradual decreasing enhancement to the peripheral area. (2) Central scar of hepatic hemangioma presents no delayed enhancement while some cases of FNH can have delayed enhancement of the central scar (FNH with thrombus in the blood vessels of central scar presents no delayed enhancement). (3) FNH usually shows distorted and thickened arteries at the focus center or its peripheral area while hepatic hemangioma rarely presents such a sign.

20.3 HIV/AIDS Related Viral Hepatitis

HIV/AIDS can also be complicated by various virus hepatitis. Even HIV and hepatitis virus can infect the same cell. Coinfection or interaction between cytokine and viral protein can make the conditions complex and progress rapidly.

20.3.1 HIV/AIDS Related Viral Hepatitis A

20.3.1.1 Pathogens and Pathogenesis

Studies on the pathogenesis of hepatitis A are rarely reported, hence, it has not been full clarified. After infection of hepatitis A virus (HAV) via the oral cavity, the patients show a short term temporary viremia before its onset. After that, the virus is located in the liver. It was believed that HIV has direct destructive effects on the hepatic cells. However, recent studies have demonstrated that its pathogenesis is mainly predisposed to be immune responses of the host. In the early stage after its onset, HAV proliferates in large quantity in the hepatic cells, together with the toxic effects of CD8 on T cells, the hepatic cells are damaged. In the later stage after its onset, the lesions are predominantly pathological changes of the defense mechanism.

20.3.1.2 Pathophysiological Basis

Hepatitis A mainly presents acute hepatitis lesions and can also cause cholestatic hepatitis and severe hepatitis. Its principal pathological changes are as the following. (1) Degeneration and necrosis of the hepatic cells. The most common is early swelling of the hepatic cells in balloon sign, with accompanying hepatocyte acidophilic degenerations and formation of acidophilic bodies, which leads to loss of hepatic sinuses. Subsequently, the hepatocytes in the hepatic lobules are disorderly arranged, with lytic necrosis of the hepatocytes around central veins of hepatic lobules. (2) Inflammatory cells infiltration is found in the portal area, mostly large monocytes and lymphocytes. (3) Kupffer cell hyperplasia in the sinusoid wall. The above pathological changes are reversible, which may recover to normal in 1–2 months after receding of jaundice. The lesions of jaundice hepatitis A and non-jaundice hepatitis A are similar lesions, but the cases of non-jaundice hepatitis A having relatively mild symptoms.

20.3.1.3 Clinical Symptoms and Signs

After infection of hepatitis A virus, generally there is about 1 month asymptomatic incubation period. Subsequently, symptoms of unknown causes occur, including fever, fatigue, poor appetite, nausea, vomiting and yellow skin. In some cases, there are also abdominal distension or diarrhea. The urine is in brown and the stool light-colored. Liver examination shows hepatomegaly and tenderness or percussion pain.

20.3.1.4 Examinations and Their Selection

Blood Test

Leukocyte count decreases slightly or remains normal, while lymphocyte count increases comparatively.

Urine Test

Urobilinogen and bilirubin are positive.

Serum HAV Antibody

With positive finding.

Liver Function Test

It is the basis for the diagnosis, with increased serum GPT which can be normal in the third to fourth week, and increased serum AKP and γ-GT.

CT Scanning and MR Imaging

They are commonly used imaging examinations for the diagnosis.

20.3.2 HIV/AIDS Related Viral Hepatitis B

HIV and hepatitis B virus (HBV) have similar transmission routes, including intravenous drug abuse, hemophilia, multiple transfusions, sexual transmission and perinatal vertical transmission, all of which can cause overlapping infections. Biological behavioral changes thus occur, to complicate the clinical manifestations.

20.3.2.1 Pathogens and Pathogenesis

Although HBV is a hepatotrophic virus and HIV is a non-hepatotrophic virus, studies have demonstrated that HBV can also infect T lymphocytes. Thereby these viruses can intracellularly meet in the infected patients. Consequently, mutual promotion of genetic transcription and replication between these two species of viruses can accelerate their progressions and aggravate the conditions. The HBV infection by HIV positive patients presents a poorer prognosis. Patients with HBV infection are more susceptible to HIV infection.

20.3.2.2 Pathophysiological Basis

In HBV infected patients, the histological changes include characteristic ground glass liked hepatocytes and cytoplasm containing HBsAg. The disease commonly has chronic hepatitis manifestations, with non-specific reactive hepatitis in the slight cases but fragmental necrosis and bridging necrosis in the severe cases. There are also portal fibrosis and its peripheral septal fibrosis, infiltration of lymphocytes, plasmocytes and histocytes in the portal area, as well as balloon like changes of the hepatocytes and acidophilic necrosis of the hepatocytes. In the advanced stage, the typical changes are formation of pseudolobule and even fibrosis.

20.3.2.3 Clinical Symptoms and Signs

The clinical manifestations are predominantly chronic hepatitis, with the symptoms of fatigue, poor appetite, jaundice and hepatalgia. By physical examinations, there is enlarged hardened liver. With its progression, hepatocirrhosis related symptoms and signs occur.

20.3.2.4 Examinations and Their Selections

Liver Function Test

The result is the important basis for the definitive diagnosis.

CT Scanning and MR Imaging

Both are commonly used imaging examinations.

Ultrasound

It is a commonly used diagnostic examination and can be applied for screening and follow-up examination but it fails to define the qualitative diagnosis.

Pathological Examination of Liver Tissues

The pathological findings are the golden criteria for its definitive diagnosis. In addition, it also provides information as the golden criteria for accessing the inflammation activity, fibrosis degree and therapeutic efficacy.

20.3.2.5 Imaging Demonstrations

CT scanning and MR imaging are ordered for patients with hepatitis to detect hepatocellular liver cancer. Imaging demonstrations of hepatitis are non-specific. CT scanning demonstrates acute hepatitis as hepatomegaly, diffuse adipose degenerations, thickened biliary wall and low density area around the portal veins due to edema. MR imaging demonstrates hepatitis as high signal by T2WI and prolonged relaxation of hepatic T1 and T2 due to peripheral edema of the portal veins. In the cases of chronic hepatitis, enhanced MR imaging with injection can distinguish fibrosis from concurrent or recent occurrence of hepatocellular lesions. About 70 % patients present early flaky enhancement, which is histologically confirmed as liver inflammation. About 95 % patients show late linear enhancement, which is histologically confirmed as fibrosis.

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree