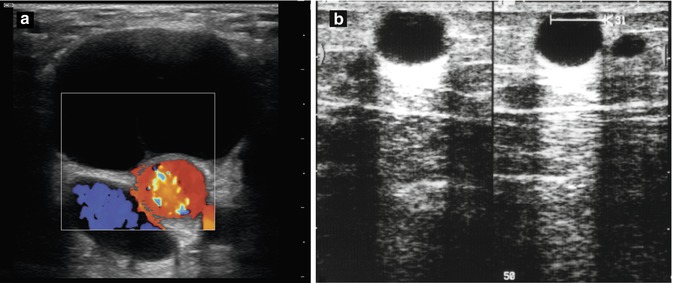

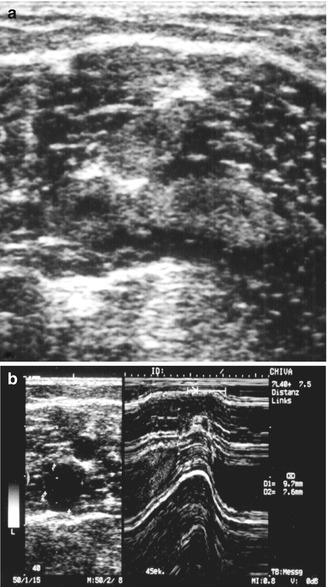

Fig. 17.1

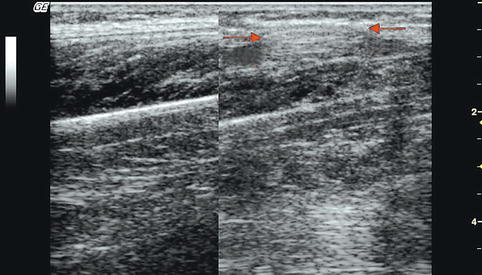

Lymph nodes. (a) Transverse view through the right groin demonstrating enlarged lymph nodes (LN). (b) Transverse view 0.5 cm further distal during muscular diastole in colour duplex. The lymph node is in contact with the refluxive vein which may even flow through the node (see accompanying online material). (c) Transverse view through the right groin in a patient with a venous ulcer: the lymph node (red arrows) lies between the great saphenous vein and the anterior accessory saphenous vein (unlabelled). Both veins are refluxive on colour duplex. The contours of the lymph node are smooth which lessens their chance of being malignant. The node demonstrated has mixed areas of chronic and acute inflammation. (d) Transverse view of a large, acutely inflamed lymph node in the left groin due to erysipelas. Note the wide echo-lucent (black) border. (e) Longitudinal view of a malignant lymph node in the left groin. This patient presented with increasing swelling of the left leg for 4 weeks. Multiple lymph nodes are demonstrated with irregular borders that are partially inseparable from the surroundings

Copyright: [Author]

Acute inflammation: large, homogeneously echo lucent (Fig. 17.1c, d)

Malignant: large, heterogeneous, echo-lucent areas with absence of an internal structure (Fig. 17.1e)

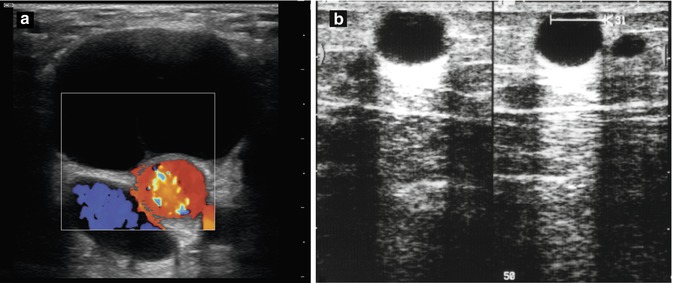

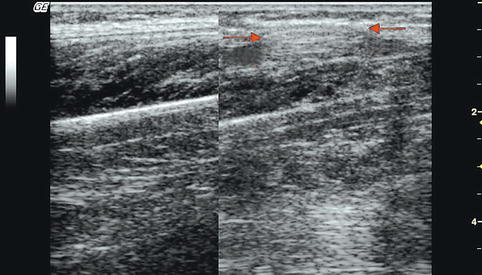

After groin surgery a lymphatic collection may develop. Occasionally this erupts as a cutaneous lymph fistula. On B-scan this appears as an echo-lucent structure separating the other tissues or forming a smooth-edged lymphatic cyst. On colour duplex there is no flow (Fig. 17.2a).

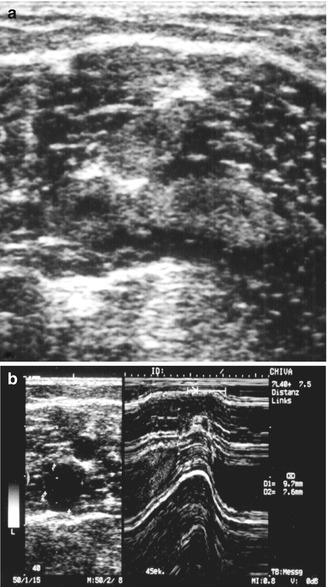

Fig. 17.2

(a) Lymphatic cyst in the left groin 3 months after cannulation of the femoral artery for cardiopulmonary bypass. Lymphatic cysts with arteries and/or veins flowing through them have a smooth border. Those without have an echo reinforcement (see accompanying online material). (b) B-scan of the thigh at the level of the adductor canal (left, longitudinal; right, transverse). A great saphenous vein tributary was ligated 8 weeks previously. The patient had a painful, tender, indurated area in the region of the scar. A lymphatic cyst appears as an echo-lucent expansion with a strong acoustic shadow, 11 × 13 × 10 mm in size. In transverse view the great saphenous vein tributary is visible

Copyright: [Author]

Lymphatic cysts are round, smooth-edged structures with a strong acoustic shadow. They may develop after trauma or from iatrogenic causes like previous surgery (Fig. 17.2b).

Occasionally a Valsalva manoeuvre may interfere with the ultrasound view of the saphenofemoral junction because of the descent of an inguinal hernia. Reducible hernias can be controlled with groin pressure by the patient in order to facilitate the examination.

Calcifications of the arterial wall appear as white, usually irregular alterations to the wall with a prominent acoustic shadow. They represent dystrophic calcification in a degenerative arterial wall which indicates arterial disease (Fig. 17.3a).

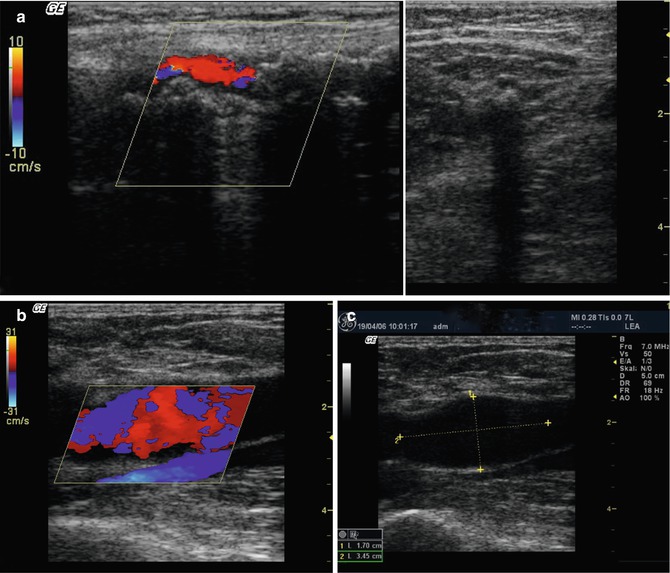

Fig. 17.3

(a) Calcification of the femoral artery. Left, longitudinal view through the groin showing a completely calcified common femoral artery with a prominent acoustic shadow. Blood flow is visible within a narrowed lumen. Right, transverse view through the inner thigh demonstrating a calcified femoral artery casting an acoustic shadow. (b) Longitudinal view of a common femoral artery aneurysm with turbulent flow (see accompanying online material). (c) The diameter of this aneurysm is 17 mm

Copyright: [Author]

The diameter of arteries enlarges with age. An excessive generalised dilatation is termed arteriomegaly. Saccular or fusiform dilatation is called an aneurysm. Their walls are often calcified with turbulent flow (Fig. 17.3b) and laminated thrombus (Fig. 17.5) in the lumen.

After interventions requiring femoral artery cannulation, an expansible, pulsatile swelling may develop. It gradually increases in size causing discolouration of the overlying skin with eventual rupture. It is caused by blood leaking from the puncture site and is termed a false aneurysm. Rupture into an adjacent vein results in an arteriovenous fistula, which is common in IV drug abuse (see Fig. 6.2). These expansible lesions differ from lymphatic cysts because they demonstrate flow in the region of the echo-lucent space. Furthermore, an extensive visible subcutaneous haematoma is usually present. They can be sealed by direct compression (30 min to hours) with the ultrasound probe, surgical repair or by a percutaneous injection of thrombin under ultrasound guidance.

Occluded arteries are visible as an echo-poor structure without flow on colour duplex. After an arterial bypass, the blood flow can be seen in the bypass graft just as easily as in the native vessel. If the volume flow diminishes, then the patient is advised to seek urgent advice from a vascular surgeon. Areas of increased velocity are usually indicative of a stenosis.

The ultrasound appearances of thromboangiitis obliterans (von Winiwarter-Buerger’s disease) consist of arterial as well as venous wall changes typically in men <40 years. Atherosclerosis is identified in the arteries with characteristic corkscrew-like collateral vessels attempting to bypass arterial occlusions.

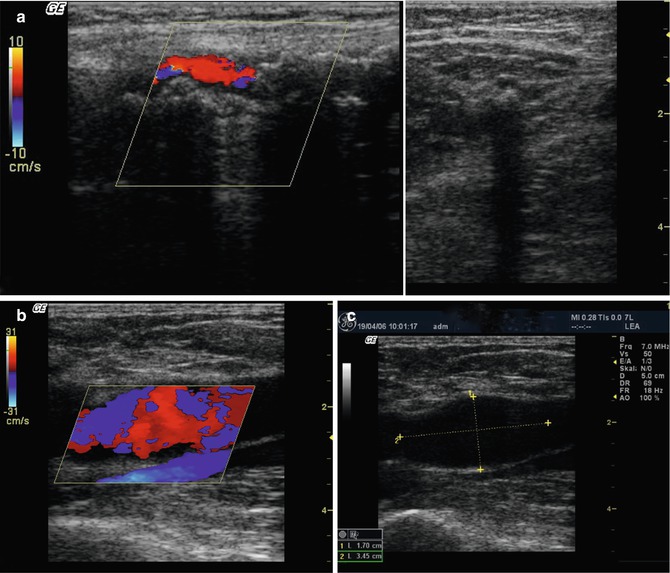

17.2 Findings in the Popliteal Fossa

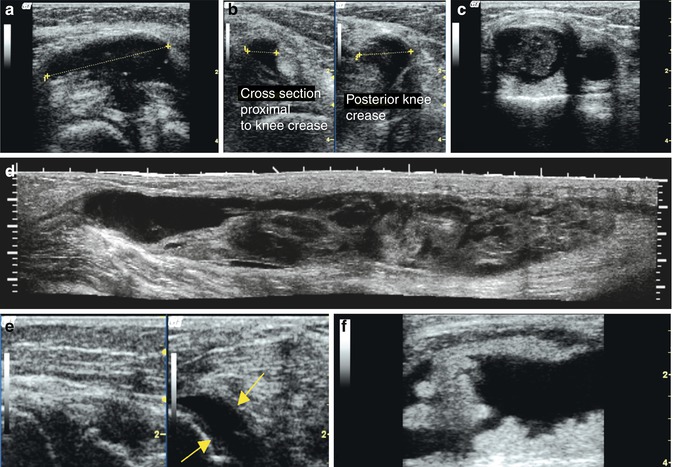

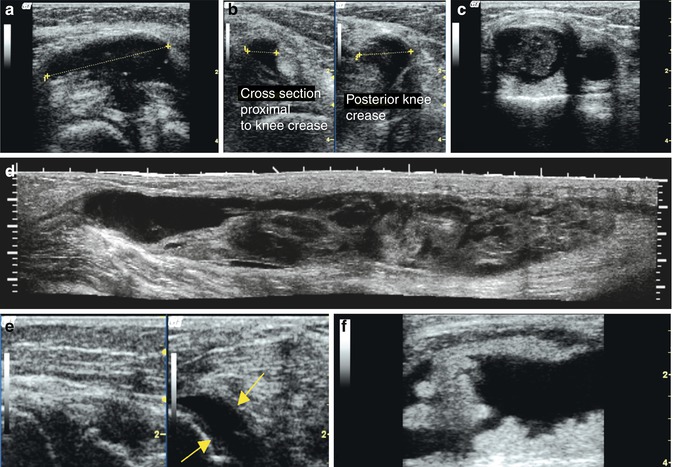

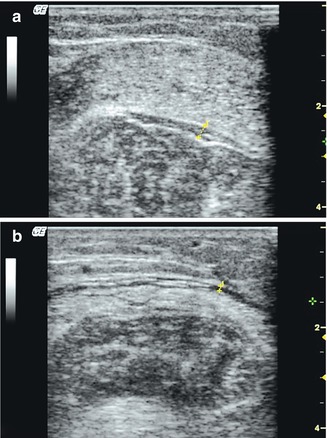

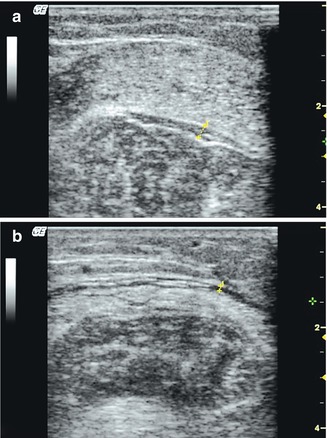

A Baker’s cyst is an echo-lucent fluid collection which accumulates behind the knee. It is an expansion filled with synovial fluid. It typically occurs in the popliteal fossa but can also appear laterally or medially. A communication with the knee joint is suspected because the cyst runs towards it in a wedge shape (Fig. 17.4a, b). However, a Baker’s cyst can also be completely round (Fig. 14.6c), haemorrhagic or divided into chambers. In the two latter cases, the internal echo is not homogeneous (Fig. 17.4c, d). A Baker’s cyst may be asymptomatic or it may compress surrounding structures, especially veins and nerves, and sometimes cause pain due to pressure (Fig. 17.4e). Rupture causes severe acute pain with swelling in the calf and reddening of the skin.

Fig. 17.4

Baker’s cyst. (a) Longitudinal view through the right popliteal region. Baker’s cyst measured at a length of 3.6 cm. The cyst points towards the knee joint (see accompanying online material). (b) Transverse view of the same knee. The left half of the image shows the proximal, rather narrower section of the cyst which corresponds to the left half of the previous image. The right half of the image shows the transverse view through the joint with the communication as mentioned above (see accompanying online material). (c) Longitudinal view through the medial popliteal region of the right leg of a patient with a painful, expanding tumour that has been increasing throughout the last 6 months. A partially solid, partially liquid-filled neoformation can be seen. It is not compressible and has no flow on colour duplex. The tumour seems to be adjacent to the bone, and the first idea was a malignant neoformation. Further examination using high-resolution ultrasound (in a clinic) resulted in a mistaken diagnosis of malignancy. The clinical history of intermittent expansion and partial resolution over 4 years confirmed the correct diagnosis of a Baker’s cyst with old haemorrhagic complications that organise and solidify over time (see accompanying online material). (d) Ruptured Baker’s cyst. Although the clinical diagnosis can be difficult, the ultrasound appearances are usually able to make the diagnosis. Using panoramic ultrasound a fluid-filled sinus is seen in the calf extending over 23 cm, 3 days after the clinical event. (e) Knee joint effusion after fall demonstrating free fluid separating the sides of the joint (arrowed). (f) Longitudinal view of the thigh just above the patella demonstrating chronic retropatellar bursitis. There is fluid extension into the thigh (right side) with internal echoes representing joint debris (see accompanying online material)

Copyright: Fig. d: Dr. Weskott

Patients with an acute rupture of a Baker’s cyst are often referred with a suspected deep vein thrombosis because the clinical appearance of the leg is similar. A ruptured cyst can be monitored in B-scan. Black, echo-lucent bands of fluid can be seen separating the layers of tissue. The tissues become oedematous with similar appearances as the surrounding oedema characteristic of the inflammation of a periphlebitis (Figs. 17.4d and 11.2). A ruptured Baker’s cyst is a common finding in the event of an acute pain in the knee or calf. The more serious condition of a deep vein thrombosis should always be excluded.

Baker’s cysts are usually part of an arthritic process which may undergo repeated rupture and haemorrhage as well as inflammation and scar formation. Over time, this results in a hard expanding lesion with heterogeneous internal echoes and irregular margins. This can be differentiated from a malignant tumour by the presence or absence of flow on colour duplex. A tumour has a pathological circulation, whilst a mature Baker’s cyst consists of scarring and old haematoma (Fig. 17.4c). Synovial fluid accumulation may occur also at the head of the fibula or subcutaneously which may be seen to communicate with the joint.

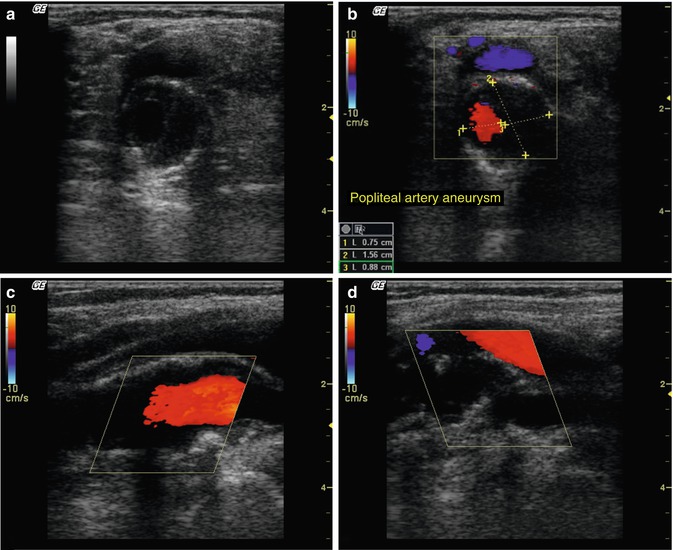

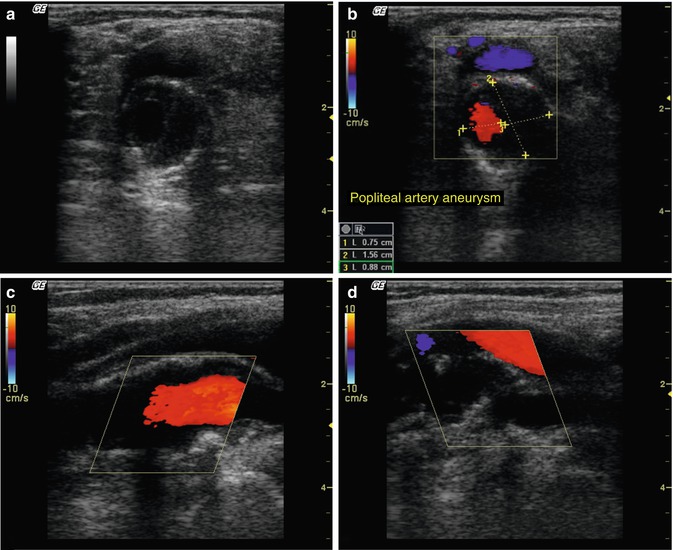

Popliteal artery aneurysms are visualised easily using ultrasound (Fig. 17.5). Colour duplex confirms they have not thrombosed since thrombosis may be a cause of acute limb ischaemia. They occur frequently on both sides. A maximum wall to wall diameter of 2.5 cm indicates the need for surgical repair. Popliteal artery aneurysms may progressively occlude the calf arteries or embolise into the calf and foot. Rupture is rare.

Fig. 17.5

Popliteal artery aneurysm. (a) Transverse B-scan through the popliteal aneurysm of the right leg containing a mural thrombus. The popliteal vein is compressed by the aneurysm (see accompanying online material). (b) Colour duplex demonstrates the remaining luminal area. (c) Longitudinal section through the same aneurysm (see accompanying online material). (d) Longitudinal view through the aneurysm demonstrating a tortuous lumen with irregular contours (see accompanying online material)

Copyright: [Author]

Cystic adventitial disease of the popliteal artery is rare, occurring in young men and presenting with intermittent claudication. The wall of the popliteal artery appears irregular in places with adjacent cystic areas compressing the lumen.

17.3 Findings in the Calf and Foot

Muscle hernias present as discrete superficial bulges which develop along the lateral part of the leg muscles when standing. They look like venous blow outs and can be confused with a varicose vein. These muscular hernias are usually easily differentiated clinically from a varicosity by having the patient stand with his weight on the ipsilateral leg, then with the weight off that leg, which should then make the bulge disappear. If there is still doubt, this can be resolved by duplex ultrasound. On ultrasound an interruption of the muscle fascia is seen with protruding muscle tissue. They can be caused by an overzealous phlebectomy, but they do not require treatment (Fig. 17.6).

Fig. 17.6

Muscle hernia. Longitudinal view at the middle third of the calf in a standing patient just lateral to the tibia. Left, fascia and muscle are clearly delineated; right, a little further lateral the fascia is interrupted, and the muscle hernia appears as a spindle-shaped protrusion (arrows)

Copyright: [Author] see online material

With an under- or overactive thyroid gland (hypo- or hyperthyroidism), calf oedema may occur (Chap. 16). It presents between the muscles and is deep to the muscular fascia (Fig. 17.7).

Fig. 17.7

Intermuscular oedema in a patient with thyrotoxicosis. (a) Transverse view through the calf with an echo-poor layer of oedema between the soleus and gastrocnemius muscles. This may also occur in hypothyroidism. (b) Transverse view through the same calf further up demonstrating another echo-poor layer of oedema between the muscle fascia and the gastrocnemius muscles (see online material)

Copyright: [Author]

Muscle veins including the soleal sinusoids may distend with thick “erythrocyte sludge” which gives the appearances of discrete lesions within the calf muscle. Compression or contraction of the calf should flush the veins and clarify the diagnosis (Fig. 17.8).

Fig. 17.8

Soleal sinusoids distended with “erythrocyte sludge”. (a) Transverse view through the calf with homogeneous areas in the muscle suggestive of a fatty or fibrous tumour. (b) Compression of the calf flushes the muscle veins from “erythrocyte sludge” which becomes echo lucent after compression. In M mode (right) the veins are filled with echogenic material beforehand which clears after compression

Copyright: [Author]

Inflammation of a tendon sheath

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree