Chapter 11 Clinical Presentation and Etiologies: Children present with variable degrees of pain, as well as secretions that can be serous early and progress to frank purulence. External otitis is associated with swimming and can be caused by a number of pathogens, including fungi. Otomycosis is more common in the postsurgical ear and presents in a similar fashion to a bacterial infection.1 Imaging: The diagnosis of otitis externa should be made clinically; however, the diagnosis can be made in the evaluation for possible mastoiditis. Soft tissue swelling and inflammation of the external canal in isolation, without evidence of involvement of the parotid or mastoids, may be demonstrated on computed tomography (CT) (e-Fig. 11-1). The acute inflammatory stage can be classified from mild to severe, and when infection spreads to surrounding tissues, the condition is then termed malignant or necrotizing otitis externa.2 Langerhans cell histiocytosis can infiltrate the soft tissue of the external canal but is more often associated with bony involvement (Box 11-1). e-Figure 11-1 Otitis externa in a 13-year-old with ear pain and soft tissue swelling. Clinical Presentation and Etiologies: Usually, the presentation is acute, with associated systemic symptoms of fever and leukocytosis. Pseudomonas aeruginosa is the most common cause of this severe infection of the external canal. Diabetes is a common predisposing condition; however, any condition resulting in immunodeficiency can be associated with malignant otitis externa.3–5 Children are reported to have better outcomes compared with adults. Imaging: CT shows more extensive inflammation within the external canal and can demonstrate bony destruction. Magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) with gadolinium demonstrates osteomyelitis, with increased signal on fat-suppressed T2-weighted images and abnormal enhancement, within bone. MRI is useful in confirming central skull base involvement, especially in the presence of multiple cranial nerve palsies, and in evaluating for intracranial complications. Facial nerve paralysis, intracranial extension, and additional cranial nerve involvement may result.5 Single photon emission CT (SPECT) technetium-99m bone scan is an effective way to confirm or exclude bone involvement in a patient whose condition evokes high clinical suspicion, and bone scan can be positive in the absence of osseous destruction on CT.6 Treatment: Several weeks of intravenous antibiotics are required for adequate treatment. High-resolution CT helps assess the extent of inflammation and surrounding bony involvement and is used to stratify patients into nonsevere and severe groups, with the latter offered early surgical intervention and debridement.7 Acquired cholesteatoma may present as debris or a mass within the external auditory canal (e-Fig. 11-2), as can keratosis obturans.8 Exostoses of the external canal may result from chronic inflammation caused by prolonged exposure to water. These lesions tend to be bilateral, broad based, and of bony density. e-Figure 11-2 Acquired cholesteatoma in a 5-year-old with otorrhea. Foreign bodies and osteomas can also occur in the external canal, with osteomas appearing pedunculated and very dense (e-Fig. 11-3).9 e-Figure 11-3 Foreign body. Clinical Presentation and Etiologies: Otitis media is the most common childhood infection that is treated with antibiotics. The otoscopic findings are critical to the diagnosis. Acute otitis media typically presents with fever, ear pain, and a red tympanic membrane.10 The initial cause of the infection is likely viral, but it may be bacterial or represent a secondary bacterial infection. Antibiotic therapy does appear to be moderately more effective than no treatment. Complications may occur in up to 10%, and this rate may be increasing; this could be associated with more conservative treatment.11 Clinical Presentation and Etiologies: Acute mastoiditis is the most common complication of acute otitis media and usually presents with high fever and elevated systemic inflammatory markers. Bacterial infections are most commonly caused by Streptococcus pneumoniae and group A beta-hemolytic streptococci. Nonbacterial causes include tuberculosis and fungal infections. Disease in the very young or infections that are not responsive to antibiotic therapy should raise the suspicion of an atypical infection or possible Langerhans cell histiocytosis.12 Facial nerve paralysis is uncommon in bacterial mastoiditis and usually is temporary, which may suggest atypical etiologies. Complications of acute mastoiditis are common, reported in up to 25% of cases.13–15 Imaging: Mastoid air fluid levels can be seen in uncomplicated acute mastoiditis; however, the diagnosis remains a clinical diagnosis. Imaging becomes useful in evaluating for possible complications of acute mastoiditis, with CT being the primary acute imaging modality. CT facilitates the diagnosis of complications of mastoiditis with a high sensitivity and positive predictive value.16 MRI and magnetic resonance venography (MRV) are valuable in assessing intracranial involvement and associated dural sinus thrombosis. The initial CT finding is decreased definition of the mastoid trabeculae caused by inflammatory hyperemia. As the trabeculae are absorbed and periostitis develops, coalescent mastoiditis develops with infected fluid within the mastoid.17 The subsequent development of a subperiosteal abscess is, by far, the most common complication and typically occurs in the postauricular region where bone is thin, termed the Macewen triangle. CT demonstrates a rim-enhancing fluid collection that is adhering close to bone; underlying bone is usually intact but may show focal destruction (Fig. 11-4). The abscess rarely may arise from the zygomatic root and present with an abscess anterior to the ear. The infection may also progress inferiorly through the mastoid tip, resulting in a Bezold abscess (e-Fig. 11-5). The eustachian tube allows infection to spread into the retropharyngeal space, and children with mastoiditis may present with a retropharyngeal abscess. Figure 11-4 Mastoiditis in a 2-year-old with post auricular swelling. e-Figure 11-5 Complicated mastoiditis. Mastoid infection may extend to the petrous apex and central skull base though the continuous mucosal spaces, resulting in petrous apicitis and osteomyelitis, respectively. Petrous apicitis classically presents as the clinical Gradenigo triad of purulent otorrhea, pain in the distribution of the fifth cranial nerve, and ipsilateral sixth cranial nerve palsy.18 CT demonstrates bony destruction and associated epidural empyema, but normal asymmetric pneumatization may make evaluation difficult. MRI demonstrates a peripherally enhancing fluid collection within the apex, and diffusion-weighted images show restricted diffusion with associated empyema or, less commonly, brain abscess (Fig. 11-6). Figure 11-6 Petrous apicitis. The major pathways that allow infectious intracranial extension include bone erosion, thrombophlebitis, and preformed pathways. The oval and round windows, cochlear and vestibular aqueducts, internal auditory canal, dehiscent tegmen, and patent petrosquamosal suture are preformed pathways that allow early or late intracranial extension. These pathways may lead to the development of suppurative labyrinthitis, as shown by abnormal enhancement of the internal auditory canal and membranous labyrinth (e-Fig. 11-7). Meningitis can occur via these pathways by spread to the subarachnoid space.17 e-Figure 11-7 Suppurative labyrinthitis. Meningitis, epidural empyema, dural sinus thrombosis, and cerebellar or cerebral abscesses are the most common intracranial complications. Bony erosion commonly involves the relatively thin sigmoid plate (Trautmann triangle) and may result in an epidural empyema or anterior lateral cerebellar abscess. Usually, significant compression of the adjacent sigmoid sinus occurs, and it may be difficult to distinguish between extrinsic mass effect and thrombosis of the sinus. Erosion through the tegmen results in a middle cranial fossa epidural empyema and or temporal lobe abscess (Fig. 11-8). Veins allow organisms to readily traverse both bone and dura, resulting in thrombophlebitis and spread of infection. The sigmoid sinus is the most common to become thrombosed; however, the lateral, petrosal, and cavernous sinuses may be involved, especially with infection of the petrous apex.17,19,20 Venous sinus thrombosis may lead to venous infarctions or otitic hydrocephalus caused by impaired venous drainage.21 MRI and gadolinium-enhanced MRV can be helpful in diagnosing dural sinus thrombosis (e-Fig. 11-9). Diffusion-weighted images show purulent material to have increased signal, which may be especially helpful in postoperative imaging (Fig. 11-10 and Box 11-2).19 Figure 11-8 Brian abscess.

Infection and Inflammation

External Ear

Axial postcontrast computed tomography through the level of the external canal shows extensive inflammation surrounding the left external canal (arrow) with normal aeration of the adjacent mastoids and a normal parotid gland (not shown).

Malignant (Necrotizing) Otitis Externa

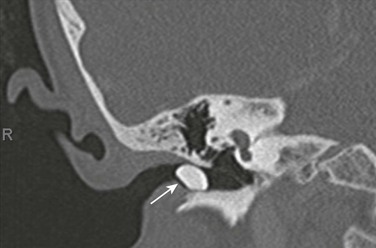

Other Lesions Encountered Within the External Auditory Canal

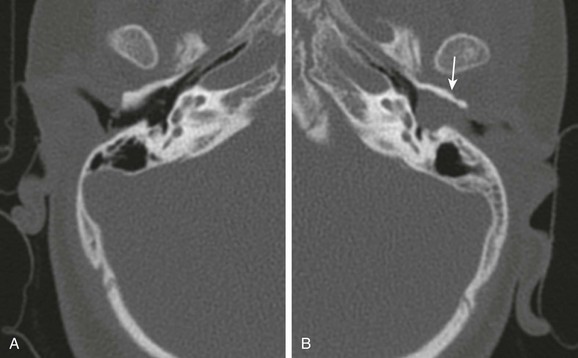

A, Axial computed tomography image through the normal right external canal. B, Axial computed tomography image through the left external canal. A large soft tissue mass with erosion of the anterior wall (arrow) is present. The tympanic membrane bulges medially with findings representing an external canal cholesteatoma.

An 8-year-old with mass in the external canal. Axial computed tomography image demonstrates a dense mass in the external canal. Surgery revealed the mass to represent a foreign body rather than an osteoma, but both should be considered.

Mastoid and Middle Ear

Otitis Media

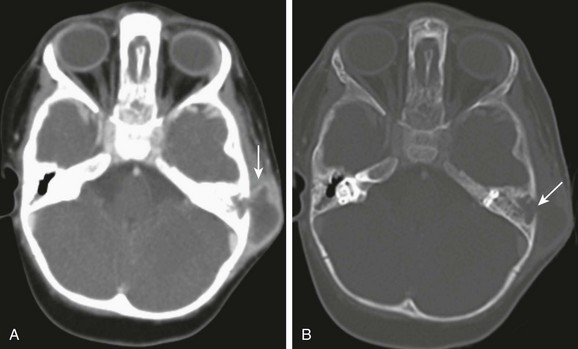

Mastoiditis

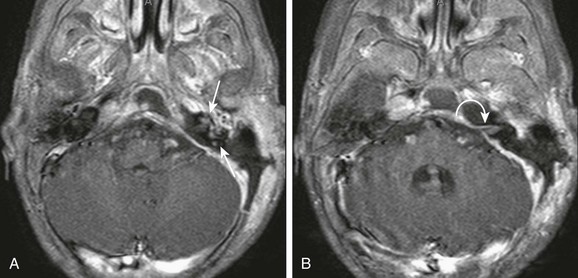

A, Axial computed tomography image through the mastoids shows a large subperiosteal abscess (arrow). B, Axial computed tomography with bone windows demonstrates destruction of the lateral mastoid wall (arrow). No intracranial extension is present with a normally enhancing sigmoid sinus.

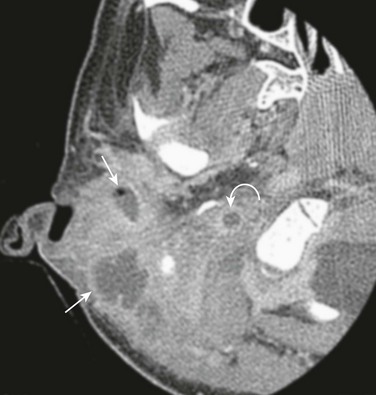

Axial postcontrast computed tomography shows a Bezold abscess inferior to the mastoids (arrows) with the anterior fluid collection containing air. Thrombosis of the internal jugular vein is also present (curved arrow). (Case courtesy of L Gibert Vezina MD.)

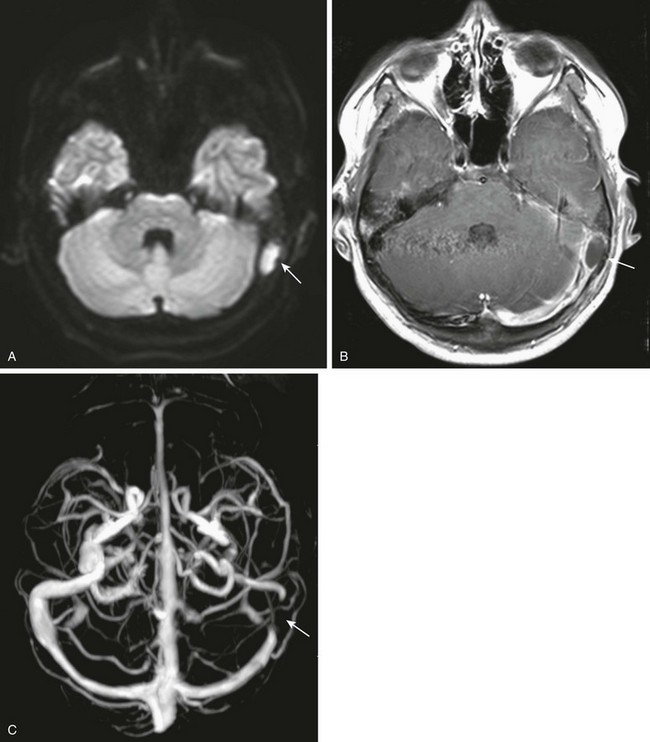

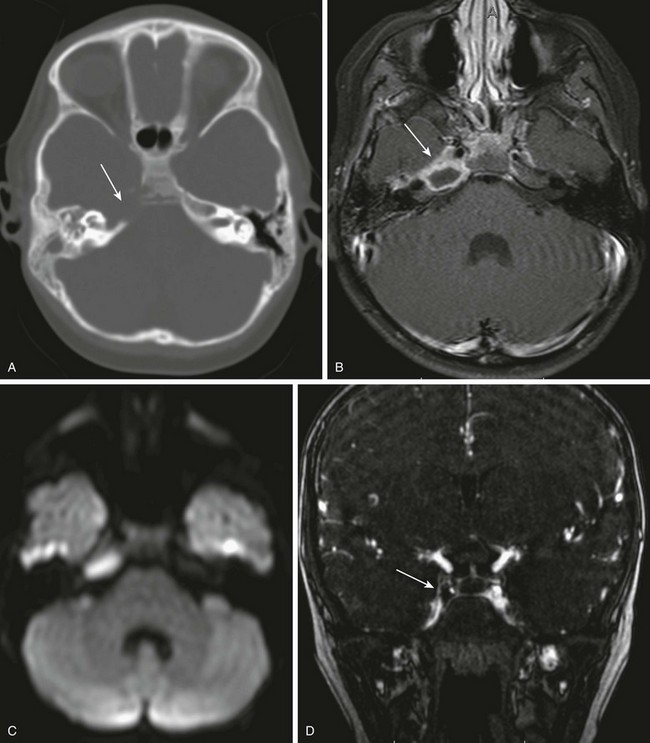

A 6-year-old with headache and right sixth nerve palsy. A, Axial computed tomography shows absence of the right petrous apex (arrow). B, Axial post-gadolinium T1-weighted images show a rim-enhancing fluid collection in the right petrous apex with associated dural enhancement. The left internal carotid artery is narrowed, likely relating to inflammation within the cavernous sinus (arrow). C, Restricted diffusion is present on the axial diffusion-weighted image. D, Gadolinium-enhanced magnetic resonance venography shows a filling defect in the right cavernous sinus consistent with thrombosis (arrow).

An 18-month-old with mastoiditis. A and B, Axial post-gadolinium T1-weighted images through the membranous labyrinth. Extensive peripheral enhancement throughout the mastoids and extension to the central skull base along with regional dural enhancement are present. Abnormal enhancement is present within the left internal auditory canal (curved arrow), cochlea, and vestibular system (arrows), consistent with suppurative labyrinthitis. A left-sided mastoidectomy has been performed.

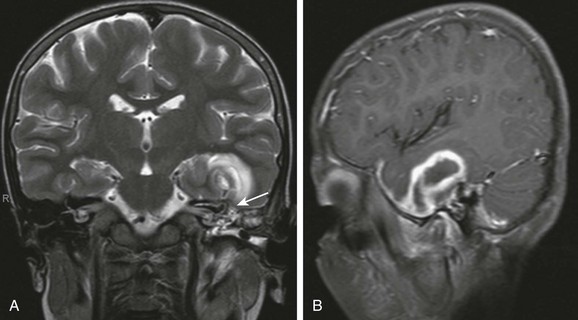

An 8-year-old with complicated mastoiditis. A, Coronal T2-weighted image shows fluid in the left mastoid and middle ear. A defect is present within the tegmen (arrow) associated with a large temporal intraaxial lesion. B, Left parasagittal post-gadolinium T1-weighted image demonstrates rim enhancement of the temporal mass, consistent with abscess.