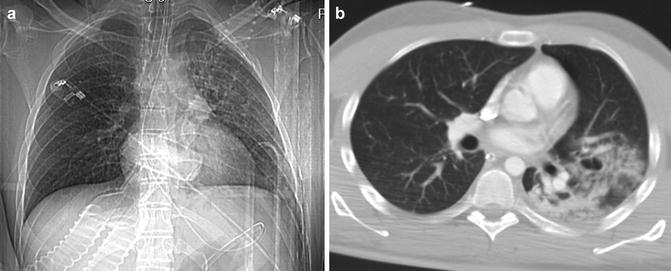

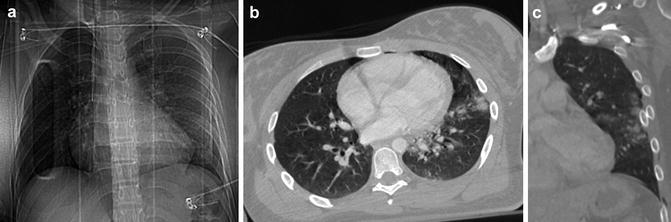

Fig. 1

(a) CXR: pulmonary contusions may appear as single or multifocal “ground-glass” area. The ground-glass pattern is indicative of an interstitial damage with partial alveolar filling. (b) Axial CT scan and (c) coronal reconstruction well depict the ground glass

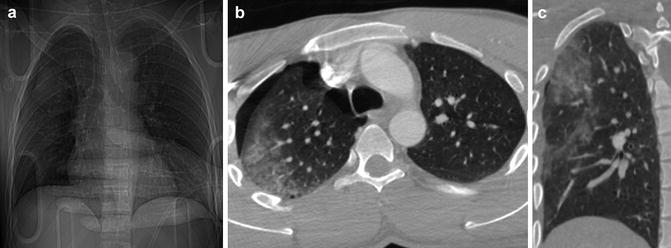

Fig. 2

(a) CXR, (b) axial CT scan, and (c) coronal reconstruction demonstrate the presence of contemporary ground-glass and parenchymal consolidation pattern

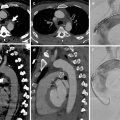

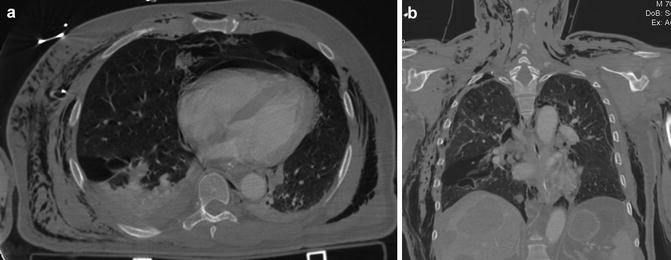

Fig. 3

(a) CXR, (b) axial CT scan, and (c) coronal reconstruction show severe contusion, which can appear as a parenchymal consolidation. The consolidation pattern is indicative of severe alveolar damage. In this patient it is associated with a wide apical ipsilateral pneumothorax

CT is highly sensitive in detecting pulmonary contusions: in experimental models, CT can detect pulmonary contusion in 100 % of cases compared with 37.5 % by chest radiographs, and it provides an accurate detection of the extent of the injury. However, there is a possibility that pulmonary contusions only visible on CT are not clinically significant. The feature on CT is dependent on the injury severity: “ground-glass opacity” is indicative of a mainly interstitial damage with partial alveolar filling, whereas consolidation is indicative of a severe alveolar damage, often associated with lacerations.

2.2 Differential Diagnosis

It may manifest as pathology of the airspaces, and differential diagnosis considers aspiration, atelectasis, and pneumonia. They all may have identical radiographic findings. Radiographic features of atelectasis include triangular shape and signs associated with volume loss; those of laceration the cavitating pattern within the radiopaque area. Lack of contusion clearance within 7–8 days should raise the suspicion of either associated laceration, pneumonia, or ARDS.

Air bronchogram sign is rare because distal airways are usually filled with blood or edema.

3 Pulmonary Laceration

Pulmonary lacerations are evident tears in the lung parenchyma, usually resulting either from shearing stress forces, secondary to high-energy trauma, or from direct puncture, i.e., due to fractured rib fragments. They may be associated with contusions that should represent a minor parenchymal damage. Clinically, pulmonary lacerations may manifest as hemoptysis.

Multiple types of lacerations can be seen in the same injured parenchyma simultaneously. They are usually benign lesions, although some complications may arise: infection, bronchopleural fistula, enlargement and subsequent compression of the surrounding parenchyma, and hemorrhage.

3.1 Diagnostic Imaging

The radiographic findings are variable and can change after admission to ED in subsequent examinations. The elastic recoil properties of the surrounding lung parenchyma give a round shape to the lacerations that are often difficult to identify on CXR. The space created by the tissue disruption may be filled with air, blood (hematoma), or more often both air and blood, creating air-fluid levels. In the acute stage, the blood, collected in the laceration, shows up a well-defined homogenous opacity, with density of soft tissue. Lacerations, sometimes masked by associated pulmonary contusions, become clearly detectable on serial follow-up examination, thanks to the clearance of the contusions. Lacerations, in fact, become more visible days after the trauma, with the shrinking of the edema and the hemorrhage, both associated with contusion. On occasion, small and multiple lacerative lesions are visible within areas of parenchymal contusion, in the form of focal uniform density, with a “Swiss cheese appearance.” Within areas of contusion, the detection of round, homogeneously dense focuses, indicative of multiple hematomas, is not rare.

With time, the hematoma within the laceration resolves, and it is replaced with a round or oval air cavity, referred to as posttraumatic pneumatocele. The posttraumatic pneumatocele appears within few days from trauma, but, in some cases, it can be evident after months; its size is usually 2–5 cm.

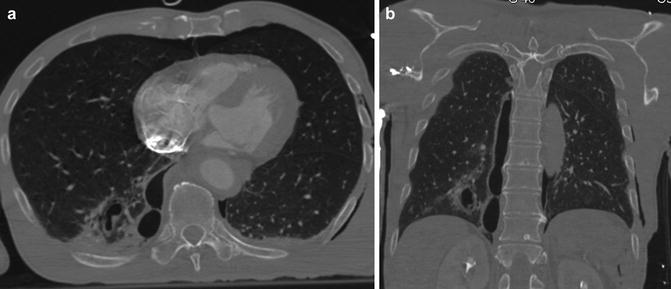

The detection of pulmonary lacerations is highly sensitive on MSCT, and, consequently, a classification into four types is possible:

Type 1: it is the most common type, centrally located; it results from shearing stress forces, developed between the lung parenchyma and the tracheobronchial tree (Fig. 4).

Fig. 4

(a) Axial CT scan, (b) coronal reconstruction: pulmonary laceration, type 1. Large parenchymal lacerations, peripherally located. In this patient, associated are pneumopericardium and extensive subcutaneous emphysema of the chest wall

Type 2: often seen as a tubular lesion in the lower lobes, resulting from a compression force of the parenchyma across the vertebral body (the spine) (Fig. 5).

Fig. 5

(a) Axial CT scan and (b) coronal reconstruction: pulmonary lacerations, type 2. They appear as tubular lesions, more frequent in lower lobes, near the spine. They are the result of a compression force of the parenchyma across the spine

Type 3: it is small, rounded, peripherally located, associated with rib fractures and a PNX (Fig. 6).