Chapter 29 Lymphoma and disease of bone marrow

Malignant lymphomas

Aetiology and epidemiology

• t(14;18)(q32;q21) in about 80% of follicular lymphoma, involving the BCL2 gene on chromosome 18q21

• t(11;14)(q13;q32) in all cases of mantle cell lymphoma, involving the Cyclin D1 gene on chromosome 11q13

• t(8:14)(q24;q32) in Burkitt’s lymphoma, involving the MYC gene on chromosome 8q24.

Pathological characteristics

Prognosis and therapy depend on the maturity and subtype of the cell of origin. This is defined by:

1. morphology – appearance and arrangement of cells

2. immunophenotyping – cellular differentiation (CD) cell surface antigens identified by a panel of antibodies

3. cytogenetics – chromosome translocations

The WHO classification includes HL and NHL (Table 29.1). A specialist haematopathologist is essential for accurate categorization. Morphologically, aggressive NHL can resemble poorly differentiated carcinoma and indolent NHL may be confused with benign lymphadenopathy.

Table 29.1 Simplified WHO classification of tumours of haematopoietic and lymphoid tissues

Chronic myeloproliferative diseases CML PRV Myelofibrosis Thrombocythemia |

Myelodysplastic/myeloproliferative diseases and syndromes Acute myeloid leukaemias AML with cytogenetic abnormalities or with prior dysplasia/therapy |

Precursor B-cell neoplasm Precursor B lymphoblastic leukaemia/lymphoma (ALL) |

Mature B-cell neoplasms CLL/small lymphocytic lymphoma Marginal zone lymphoma: splenic/nodal/MALT Myeloma and plasmacytoma Follicular lymphoma Mantle cell lymphoma Diffuse large B-cell lymphoma Mediastinal large B-cell lymphoma Burkitt’s lymphoma |

B-cell proliferations of uncertain malignant potential Post-transplant lymphoproliferative disorder |

Precursor T-cell neoplasms Precursor T-lymphoblastic leukaemia/lymphoma (ALL) |

Mature T-cell and NK-cell neoplasms T-cell and NK-cell leukaemias NK/T-cell lymphoma Peripheral T-cell lymphoma Anaplastic large cell lymphoma and cutaneous ALCL Mycosis fungoides and Sézary syndrome Angioimmunoblastic T-cell lymphoma Enteropathy-type T-cell lymphoma |

Hodgkin’s lymphoma Nodular lymphocyte predominant HL |

Classical HL Nodular sclerosis Lymphocyte-rich Mixed cellularity Lymphocyte-depleted |

Diagnosis and staging

Staging establishes the extent of the disease, using the Ann Arbor classification (Table 29.2), clinical assessment and essential investigations:

1. blood tests – full blood count, plasma viscosity, serum urea and electrolytes, calcium, liver function tests, lactate dehydrogenase (LDH) and β2-microglobulin

2. chest x-ray as baseline for reference

3. computed tomography (CT) scan of chest, abdomen and pelvis with intravenous and oral contrast

4. a bone marrow aspirate and a small core of bone (trephine) are taken from the posterior iliac crest

5. lumbar puncture for high-risk groups (see below). At the time of the procedure, it is usual to inject methotrexate 12.5 mg

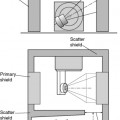

6. positron emission tomography (PET) shows uptake of fluorodeoxyglucose (FDG) into areas actively metabolizing glucose and representing viable tumour in most cases. FDG-PET can assess response where there is a residual mass on CT, which may be fibrous tissue or lymphoma. Ideally, a pretreatment scan would be available for comparison.

Table 29.2 Ann Arbor staging classification of lymphoma