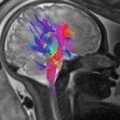

Fig. 22.1

An intravenous urogram from the archives showing the dilated right ureter tapering as it passes between the pelvic brim and the gravid uterus

The hormonal theory is that progesterone affects smooth muscle dilation causing reduced peristalsis and greater dilation. This is likely to be the predominant cause in the first trimester when the uterus is not large enough to have a mechanical effect, but thereafter, mechanical causes are predominant.

22.3 Symptomatology and Demographics

Symptoms of renal disease in pregnancy are nearly all related to infection or colic. The physiological changes of pregnancy itself may, however, also produce symptoms of abdominal or flank pain, nausea and lower urinary tract symptoms, and there may be other pregnancy-related discomforts that are harder to classify and may confuse any presentation.

Stone formation risk is higher in multiparous than primiparous women. The incidence is higher in Caucasians and those with a history of renal disease and hypertension. Up to a third of women presenting with stones in pregnancy will have a prior history of stones [5].

Flank and abdominal pain is the commonest symptom in stone disease, occurring in up to 100 % of all confirmed cases. Pain may occur in other conditions too, and consideration will need to be given to differential diagnoses such as pyelonephritis, appendicitis, diverticulitis or placental abruption. Otherwise, the main consideration is to distinguish the pain due to ureteric stones from that associated with physiological dilation. Stones usually cause more severe pain requiring greater analgesia. Left-sided pain is more likely to be due to stone [6]. Stones usually present in the second and third trimesters [7].

Frank haematuria has been reported in up to a third of women with proven ureteric calculi. Microscopic haematuria is much commoner but non-specific and is generally regarded as unhelpful in identifying stone disease [8].

Stone disease in pregnant women is associated with recurrent miscarriage, pre-eclampsia, chronic hypertension, gestational diabetes and a higher rate of Caesarean section. It is also associated with urinary tract infections. However, no increased rate of adverse perinatal outcome [9] or congenital anomaly [10] has been found. There is disagreement on the effect on preterm delivery with some studies finding no effect [9, 10] and others showing a doubling of the likelihood [11].

The prevalence of symptomatic stone disease in the pregnant population is variously quoted as between 1:200 and a much lower incidence. Most studies fall in the range of 1:200–1:300. The likelihood of a woman who is hospitalised for renal colic like pain having a stone as the underlying cause is about 20 % [12]. Some authors go so far as to state that almost a quarter of women diagnosed with stones have an inaccurate diagnosis [13].

22.4 Infections

Urinary tract infections are common in pregnant women. Pregnant women should be screened for asymptomatic bacteriuria and treated if it is present [14]. The physiological and structural changes in the pregnant woman’s urinary tract promote ascending infection from the urethra. There is a 20–50-fold increased risk of pyelonephritis in women with bacteriuria compared to those without. The prevalence of asymptomatic bacteriuria in pregnant women is around 7 % [15].

Over 70 % of asymptomatic bacteriuria infections in pregnancy are due to E. coli. The remainder is due to Klebsiella species, Proteus species (particularly in diabetics or obstructed systems), enterococci, Staphylococcus saprophyticus, pseudomonas and lastly streptococci. Antibiotic therapy during pregnancy needs to be modified to take account of the potential of some antibiotics to cause fetal harm. Tetracyclines, gentamicin and other aminoglycosides and chloramphenicol are all proven to cause fetal harm and must be avoided. Amoxicillin, ampicillin, nitrofurantoin and penicillins have been taken by large numbers of pregnant women without any proven fetal harm. It is best to check the formulary for contraindications when choosing a new antibiotic therapy.

Imaging is not needed for uncomplicated urinary tract infections that respond to treatment. If the women does not respond to antibiotics or has associated flank pain or other symptoms suggesting pyelonephritis or stones, then imaging becomes appropriate. Ultrasound is the best first-line test because of its ready availability and lack of ionising radiation.

Ultrasound features of pyelonephritis include global swelling with thickening of the urothelium. There may be loss of the normal corticomedullary differentiation and effacement of sinus echoes. Focal pyelonephritis may manifest as mass lesions of various echogenicities; some are echo-bright, whereas others are echo-poor (Fig. 22.2). The lesions may be wedge shaped and are often ill defined. The affected area usually has decreased vascularity on Doppler.

Fig. 22.2

A longitudinal ultrasound image of the kidney showing a focal segmental region of cortical hyper-echogenicity, which in the right clinical context is diagnostic of focal pyelonephritis

If the ultrasound has been unhelpful or a focal lesion needs clarification, then MR scan is the next imaging test of choice. Even in the non-pregnant patient, it has now been shown that diffusion-weighted MR scan outperforms CT in the diagnosis of pyelonephritis (sensitivities: DWI 95.3 %, non-contrast CT 66.7 % and contrast-enhanced CT 88.1 %) [16]. Likewise, diffusion-weighted imaging (DWI) performs just as well as contrast-enhanced MR in the detection of pyelonephritis, so there is no need to expose a pregnant women to gadolinium contrast agents [17]. Diffusion images can be obtained using a non-breath hold, single-shot echo-planar sequence with b values of 0, 600 and 1000. Areas of inflammation show restricted diffusion and are hypointense on T2-weighted images (Fig. 22.3). Sequential MR scans can be used to show resolution or to look for further complications such as abscess formation.

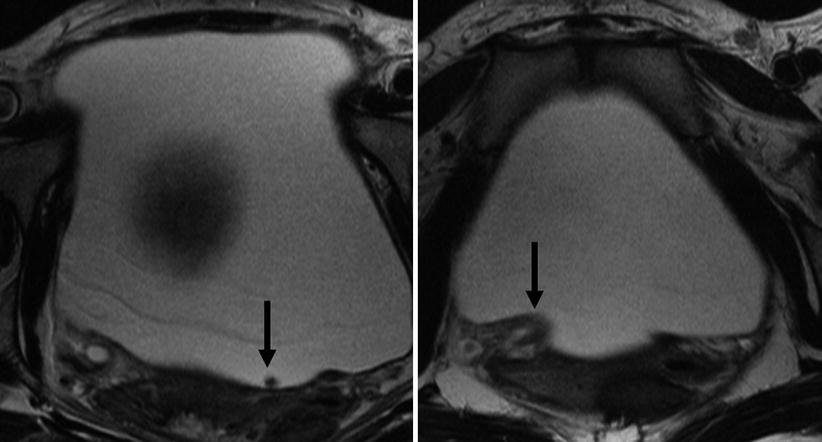

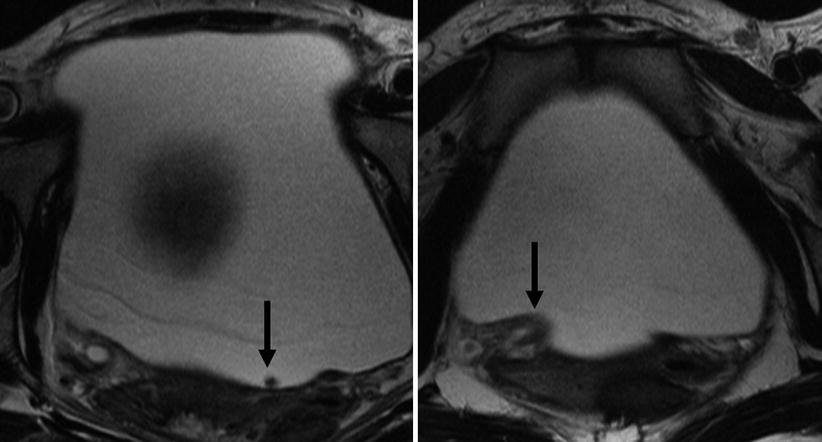

Fig. 22.3

T2-weighted (a) and diffusion-weighted (b) axial images of a focal area of pyelonephritis in the left kidney. The region is dark on T2- and bright on diffusion-weighted images. The diffusion-weighted images make the lesion more conspicuous

22.5 Renal Tract Dilation Versus Obstruction

22.5.1 Diagnosis

The essence of imaging in the presence of flank pain is to distinguish physiological dilation of the urinary tract due to pregnancy from the dilation caused by the presence of a ureteric stone. There is a very poor correlation of flank pain with the presence of hydronephrosis. A longitudinal study on pregnant women showed that many with hydronephrosis do not have any flank pain and that those with flank pain only have hydronephrosis in a third [18]. All cases resolved by 6 weeks post-partum.

22.5.2 Imaging

22.5.2.1 First-Line Imaging

Ultrasound is the primary imaging modality, agreed by all authors because of the lack of ionising radiation, ready availability and low cost. Ultrasound techniques involve identifying renal tract dilation and stones on greyscale imaging, using colour Doppler to look for the ring-down artefact from stones and to evaluate ureteric jets into the bladder and using spectral Doppler to assess the resistance index of blood flow in the interlobar arteries of the kidneys. Ultrasound is limited by the inability to view the whole ureter and by relative insensitivity to small calculi. Transvaginal ultrasound can improve visualisation of the distal ureter. Indeed, finding a dilated ureter below the level of the pelvic brim (where physiological compression is expected to occur) should alert the investigator to the possibility of a lower ureteric stone [19].

Dilation of the pelvicalyceal system alone is non-specific because of the effect of physiological dilation (Fig. 22.4). Left-sided symptoms and dilation have a higher correlation with stone disease because physiological dilation preferentially affects the right side. Renal pelvic diameter of 17 mm or less on an asymptomatic side effectively excludes the presence of stone.

Fig. 22.4

Longitudinal ultrasound image of a kidney showing quite marked pelvicalyceal dilation. This finding alone does not allow the distinction of physiological dilation of pregnancy from obstruction due to ureteric stone

Stones may be seen with ultrasound because of the focus of reflection with a posterior echo shadow (Fig. 22.5). Colour Doppler to show the ring-down artefact behind the stone can increase conspicuity (Fig. 22.6).

Fig. 22.5

(a, b) Two examples of a renal stone on ultrasound, both demonstrating posterior acoustic shadowing

Fig. 22.6

Axial greyscale ultrasound image of the bladder at the level of the ureteric orifice (a) showing a calculus impacted at the orifice. Colour Doppler image at the same level (b) showing both the ring-down artefact behind a stone and the ureteric jet phenomenon. The latter showing that the presence of a ureteric jet does not exclude a stone

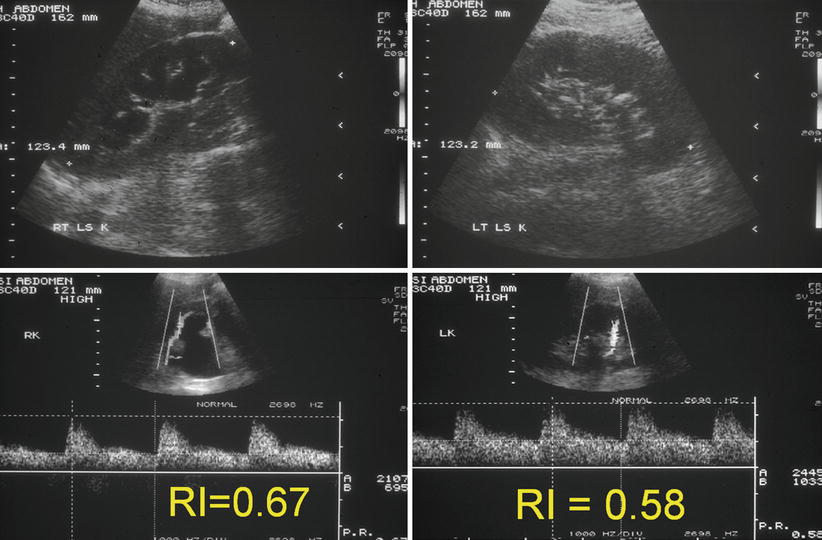

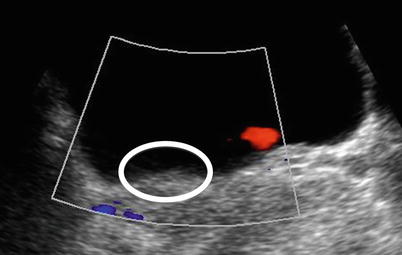

Indirect signs of the presence of a ureteral stone are a raised resistance index (RI) and an absent ureteric jet. The kidneys that have become obstructed by a stone have a raised intrarenal pressure that affects the blood flow through the kidney. This does not occur with physiological dilation. An RI over 0.70 or a difference in RI between the two kidneys of greater than 10 % correlates with the presence of a ureteral stone (Fig. 22.7). Limitations on RI are the confounding factors of prior renal disease, treatment with nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drugs and scanning within 6 h of the onset of obstruction or more than 48 h after obstruction.

Fig. 22.7

Composite set of ultrasound images of both kidneys showing greyscale appearances and the interlobar artery spectral traces. The right kidney is hydronephrotic. There is a stone in the left kidney. The resistive index in the right kidney is greater than 10 % higher than the contralateral kidney implying that the right-sided dilation is due to a ureteric calculus

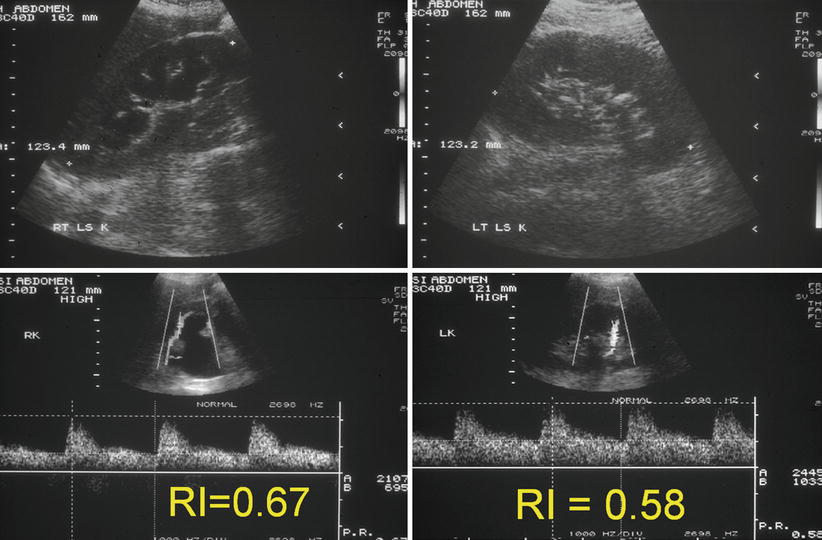

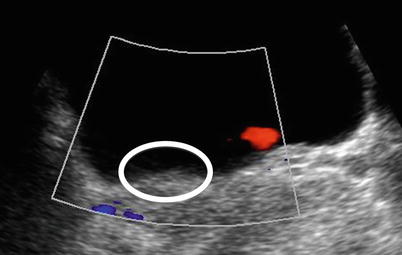

Unilateral absence of a ureteral jet into the bladder on the symptomatic side, as shown by colour Doppler, correlates with obstruction (Figs. 22.6 and 22.8). Care must be taken to image the woman in the opposite decubitus position to avoid compression of the ureter by the uterus [20, 21].

Fig. 22.8

Axial ultrasound image through the ureteric orifices. A ureteric jet is seen on the left but none on the right. The orifices should be observed together for a few minutes and the number of jets counted from both sides. A large discrepancy implies ureteric obstruction on the side with the smaller number. The circle shows the right ureteric orifice and highlights the lack of ureteric jet

Quoted ultrasound sensitivities for stone disease in pregnancy vary widely and is clearly dependent on operator expertise and the thrust of any research study. Rates vary from about a third to nearly nine out of ten cases.

22.5.2.2 Second-Line Imaging

The question arises, what should be the next step when ultrasound has not answered the clinical problem and the patient is still symptomatic despite conservative treatment? The choices lie between CT, diagnostic ureteroscopy or MR scan.

CT is undoubtedly the best test in the non-pregnant patient for the detection of urinary tract stones. It also offers an overview of the rest of the abdomen and pelvis allowing alternative causes of flank pain to be detected. The contraindication to its use in pregnancy is the radiation dose involved. This is a relative contraindication as with low-dose techniques, the dose to the fetus can be reduced to 4 mGy without losing sensitivity for stones. At this low dose, it is arguable that the risk of radiation to cause either deterministic or stochastic effects (e.g. fetal loss, teratogenicity or childhood leukaemia) is so negligible as to be considered nothing. Many authorities still advocate its use in pregnancy as shown by the compendium of guidelines published by Austin and Frush [22]. It is also recognised that CT skills and scanners are more widespread than MR and that radiologists may have far more experience in interpreting CT than MR in the pregnant patient. However, if the alternative of MR is available, then CT should be considered as the last choice given its use of radiation [23]. Repeating CT scans during pregnancy is also frowned upon because of the cumulative radiation dose.

Ureteroscopy, with or without fluoroscopy, is held by many urologists to be the next investigation step after ultrasound. The advantage is the ability to combine diagnosis with treatment [24]. General anaesthesia is used in up to two thirds of cases. It is possible to place a ureteric stent or to perform pneumatic lithotripsy with some authors reporting 100 % stone-free rates after treatment [25, 26]. An element of caution is needed as although the maternal and fetal risks are low, they are not non-existent. The rate of complications increases, the more procedures are done. One series quotes a 4 % rate of preterm delivery [27]; another describes a case of ureteral perforation [28]. In view of this, it is prudent to maximise the non-invasive imaging information prior to embarking on ureteroscopy.

In an ideal world, if ultrasound and conservative management have failed to solve the problem, then MR should be chosen as the second-line imaging test ahead of CT or ureteroscopy. MR has the advantage of not involving ionising radiation. MR without intravenous gadolinium-based contrast agents is considered a safe technique: the American College of Radiology (ACR) advises that pregnant patients can undergo MRI without risks for the fetus. MR imaging at 1.5 T or lower magnetic field strength has been used to evaluate diseases in pregnancy for over 20 years without any documented harmful effects [29]. The first trimester is generally avoided as it is difficult to establish safety because of active organogenesis. Field strengths higher than 1.5 T have not yet been proven to be safe, but as yet in the relatively short time, 3 T has been in use, there have been no adverse events reported. Theoretical risks of acoustic injury or thermal damage are limited by the manufacturers’ inbuilt limits for each pulse sequence.

Gadolinium-based contrast agents cross the placenta and are excreted by fetal kidneys into the amniotic fluid. These are classified as category C drugs by the Food and Drug Administration (FDA), i.e. animal reproduction studies have shown an adverse effect on the fetus. Well-controlled studies in humans are not available at present, but potential benefits may warrant use of the drug in pregnant women despite potential risks. For this reason, gadolinium should only be administered using the smallest dose of the most stable gadolinium agent (macrocyclic) [30] and preferably within the context of a trial.

Calculi do not themselves generate any signal on MR scan. MR needs there to be a signal generating fluid or tissue around the calculus to enable the calculus to be detected as a signal void (Fig. 22.9). MR is able to detect the secondary signs of ureteric obstruction due to stone by being able to reveal the dilated ureter, the oedema in the kidney and the perinephric fluid caused by obstruction. It has been suggested by some authors that MR can be used to define the level of obstruction, and then a limited CT scan focused on that level used to detect the stone, thereby greatly reducing the radiation dose whilst still maintaining sensitivity for stone [31]. There are clearly logistical difficulties with this approach in being able to proceed to CT straight after the MR scan such that the concept has not been adopted by other centres.

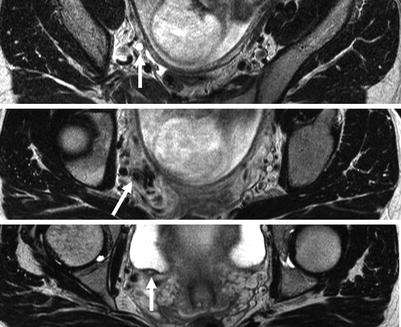

Fig. 22.9

T2-weighted axial images through the bladder. The stone in the bladder (arrow) is revealed as a signal void amongst the high signal of the urine. Note the second arrow points at the oedematous ureteric orifice implying recent passage of the stone

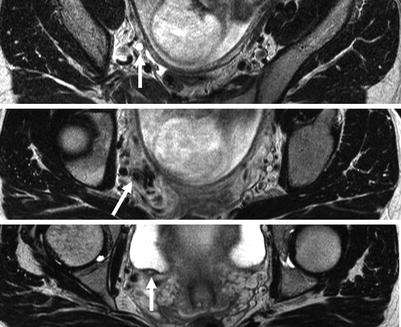

There are only a few published series of the use of MR in pregnancy-related renal colic [32, 33]. None have evaluated sensitivity or specificity for renal calculi. Generally, the larger the calculus, the more likely it is to be detected on MR. Thin-section scans increase the conspicuity of smaller stones (Fig. 22.10). However, the main limitation to high-resolution MR imaging in the pregnant patient is fetal movement. As a consequence, sequences able to generate images in a second or two are preferred with longer acquisitions reserved for imaging the level of obstruction.

Fig. 22.10

High-resolution axial T2-weighted images through the area of concern revealed by thick-slab SSFSE images allow the ureter to be traced (arrows) on sequential images and the stone revealed (on the middle image)

MR can be poorly tolerated by the pregnant patient because of claustrophobia or because of the need to lie in one position. Women in the third trimester often prefer to lie in a partial decubitus position as lying supine can allow the gravid uterus to compress the cava and cause fainting. A careful explanation of the examination and the use of wider bore scanners help to minimise the non-acceptance rate for MR.

Ideally, a radiologist should start by using coronal thick-slab SSFSE ‘MR urography images’ that provide a ‘road map’ of the urinary system (Fig. 22.11) looking for strictures or calibre changes and potential filling defects using fast imaging such as FISP and water-weighted sequences such as SSFSE and then to focus on these areas of interest using higher-resolution T2W imaging. The technique described in early reports using gadolinium as part of MR excretion urography [34] has not been adopted partly because of the unknown effects of gadolinium on the fetus and partly because it offers no advantage over MR urography using the intrinsic contrast available from urine. Showing delayed excretion on the affected side does not increase detection of stones (Fig. 22.12).