Malignant Bone Tumors I: Osteosarcomas and Chondrosarcomas

Osteosarcomas

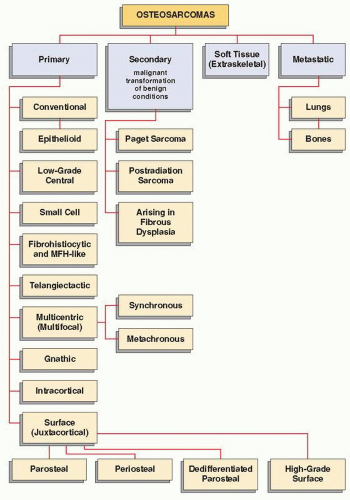

Osteosarcoma (osteogenic sarcoma) is one of the most common primary malignant bone tumors, comprising approximately 20% of all primary bone malignancies. There are several types of osteosarcoma (Fig. 21.1), each having distinctive clinical, imaging, and histologic characteristics. The common feature of all types is that the osteoid and bone matrix are formed by malignant cells of connective tissue.

The majority of osteosarcomas are of unknown cause and can therefore be referred to as idiopathic, or primary. A smaller number of tumors can be related to known factors predisposing to malignancy, such as Paget disease, fibrous dysplasia, external ionizing irradiation, or ingestion of radioactive substances. These lesions are referred to as secondary osteosarcomas. All types of osteosarcomas may be further subdivided by anatomic site into lesions of the appendicular skeleton and axial skeleton. Furthermore, they may be classified on the basis of their location in the bone as central (medullary), intracortical, and juxtacortical. A separate group consists of primary osteosarcoma originating in the soft tissues (so-called extraskeletal or soft-tissue osteosarcomas).

Histopathologically, osteosarcomas can be graded on the basis of their cellularity, nuclear pleomorphism, and degree of mitotic activity. According to Broder’s system, the numerical grade (1 to 4) indicates the degree of malignancy (grade 1 indicating the least undifferentiated tumor and grade 4 the most undifferentiated tumor) (Table 21.1). For example, well-differentiated central osteosarcomas and parosteal osteosarcomas are regarded as grade 1 or, rarely, grade 2 tumors; periosteal osteosarcomas and gnathic osteosarcomas as grade 2 or, rarely, grade 3; and conventional osteosarcoma as grade 3 or 4. Telangiectatic osteosarcomas, osteosarcomas developing in pagetic bone, postirradiation osteosarcomas, and multifocal osteosarcomas are usually grade 4 tumors. This grading has clinical, therapeutic, and prognostic importance. Generally speaking, central osteosarcomas are much more frequent than juxtacortical tumors, and they tend to have a higher histologic grade. Although pulmonary metastasis is the most common and most significant complication in high-grade osteosarcoma, it is rare in two subtypes: osteosarcoma of the jaw and multicentric osteosarcoma.

Primary Osteosarcomas

Conventional Osteosarcoma

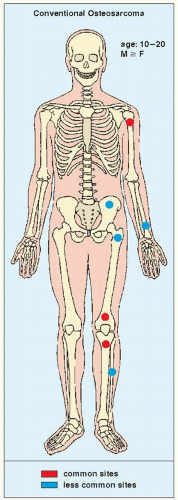

Conventional osteosarcoma is the most frequent type, having its highest incidence in patients in their second decade and affecting males slightly more often than females. It has a predilection for the knee region (distal femur and proximal tibia), whereas the second most common site is the proximal humerus (Fig. 21.2). Patients usually present with bone pain, occasionally accompanied by a soft-tissue mass or swelling. At times, the first symptoms are related to pathologic fracture.

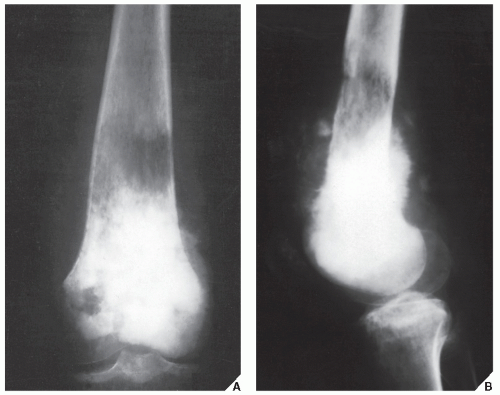

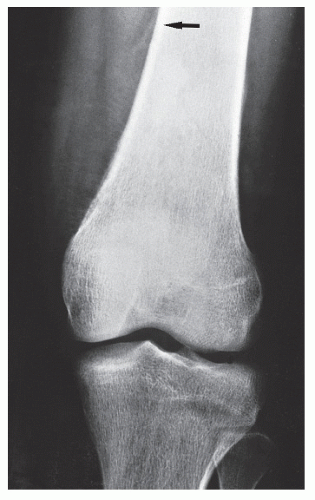

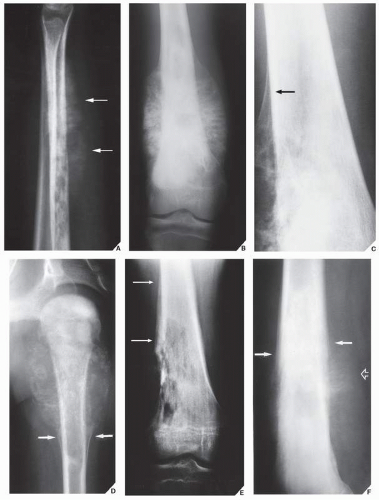

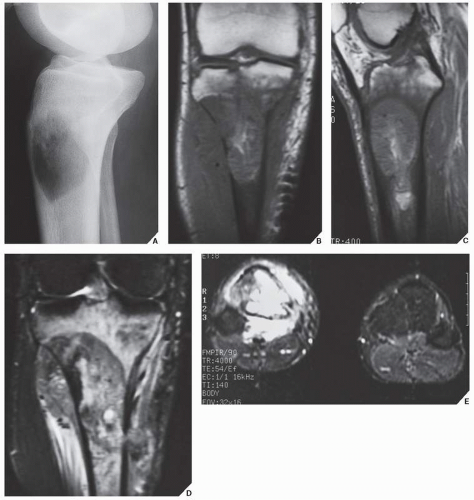

The distinctive radiologic features of conventional osteosarcoma, as demonstrated by radiography, are medullary and cortical bone destruction, an aggressive periosteal reaction, a soft-tissue mass, and tumor bone either within the destructive lesion or at its periphery, as well as within the soft-tissue mass (Fig. 21.3). In some instances, the type of bone destruction may not be obvious on the conventional studies, but patchy densities representing tumor bone and an aggressive periosteal reaction are clues to the diagnosis (Fig. 21.4).

The degree of radiopacity in the tumor reflects a combination of the amount of tumor bone production, calcified matrix, and osteoid. Tumors may present as purely sclerotic lesions or purely osteolytic lesions, but mostly a combination of both (Fig. 21.5). The borders are usually indistinct, with a wide zone of transition. The type of bone destruction is either moth-eaten or permeative, and only rarely geographic.

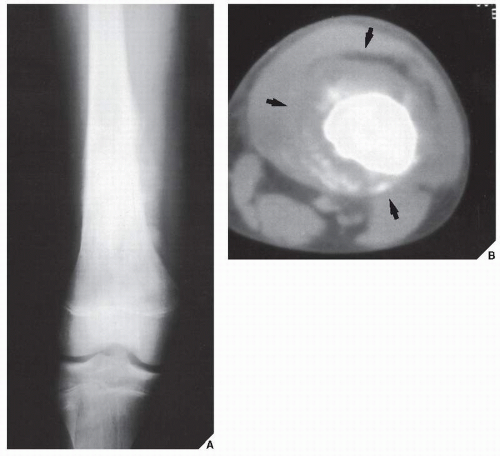

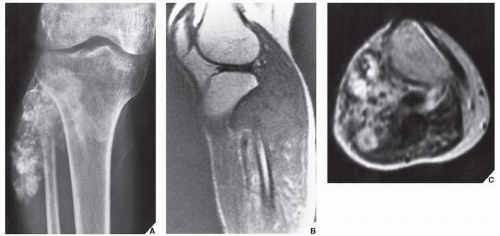

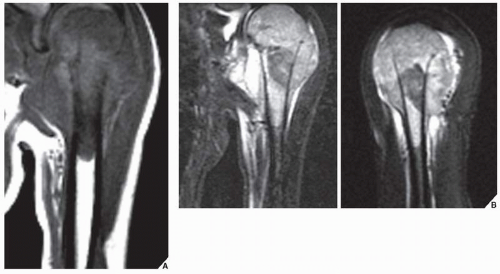

The most common types of periosteal response encountered with osteosarcoma are the “sunburst” type and a Codman triangle; the lamellated (onionskin) type of reaction is less frequently seen (Fig. 21.6). In the past, computed tomography (CT) was an indispensable technique for evaluating these tumors (Fig. 21.7). This was particularly important if a limb-salvage procedure was contemplated because extension of the tumor into the medullary cavity is crucial information for effective surgical planning (see Fig. 16.11). Currently, magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) has become a modality of choice for evaluating these tumors, particularly for intraosseous tumor extension and soft-tissue involvement. On T1-weighted images, the solid nonmineralized parts of osteosarcoma generally present as areas of low to intermediate signal intensity. On T2-weighted images, the tumor demonstrates a high signal intensity (Figs. 21.8,21.9,21.10). Osteosclerotic tumors demonstrate low signal intensity on all imaging sequences (Fig. 21.11). MRI may also effectively demonstrate peritumoral edema. This feature displays an intermediate intensity signal on T1-weighted and a high intensity on T2-weighted images and is seen in the soft tissues surrounding the tumor. CT (see Fig. 16.12) and MRI are also essential in monitoring the results of treatment.

Based on the dominant histologic features, conventional osteosarcoma can be subdivided into three histologic subtypes: osteoblastic, chondroblastic, and fibroblastic. The last may occasionally mimic

malignant fibrous histiocytoma (MFH). At times, the tumor cells may be so undifferentiated that on a purely cytologic basis, it is difficult to tell whether they are sarcomatous or epithelial. This variant of conventional osteosarcoma is sometimes referred to as epithelioid osteosarcoma. The diagnosis usually becomes evident from the patient’s age, the production of obvious tumor matrix, and a radiographic appearance typical of osteosarcoma.

malignant fibrous histiocytoma (MFH). At times, the tumor cells may be so undifferentiated that on a purely cytologic basis, it is difficult to tell whether they are sarcomatous or epithelial. This variant of conventional osteosarcoma is sometimes referred to as epithelioid osteosarcoma. The diagnosis usually becomes evident from the patient’s age, the production of obvious tumor matrix, and a radiographic appearance typical of osteosarcoma.

TABLE 21.1 Histologic Grading of Osteosarcoma | ||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| ||||||||||||

FIGURE 21.2 Skeletal sites of predilection, peak age range, and male-to-female ratio in conventional osteosarcoma. |

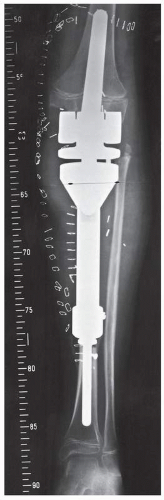

Complications and Treatment. The most frequent complications of conventional osteosarcoma are pathologic fracture and the development of pulmonary metastases.

If a limb-salvage procedure is feasible, a course of multidrug chemotherapy is used, followed by wide resection of the bone and insertion of an endoprosthesis (Fig. 21.12). Less frequently, amputation is performed, followed by chemotherapy. Currently, the 5-year survival rate after adequate therapy exceeds 50%.

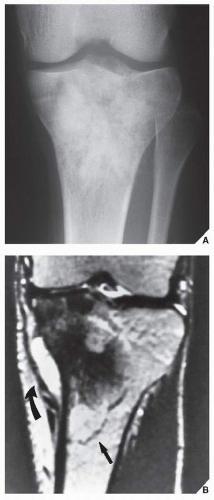

Low-Grade Central Osteosarcoma

This rare form of osteosarcoma (1% of all osteosarcomas) usually occurs in patients older than those presenting with conventional osteosarcoma, although the sites of predilection are similar. Radiographically, it may be indistinguishable from conventional osteosarcoma, but it grows more slowly and has a better prognosis. At times, its radiographic presentation clearly mimics fibrous dysplasia (Fig. 21.13) or other benign lesion (Fig. 21.14). Histologic examination typically reveals abundant osteoid and spindle cells with a paucity of cellular atypia and mitotic figures.

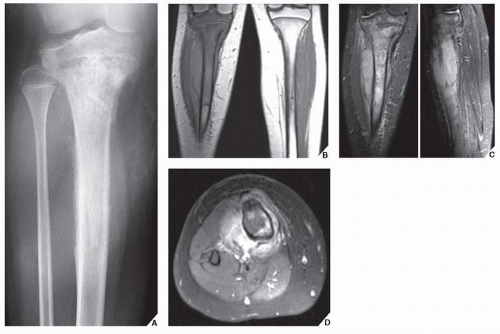

Telangiectatic Osteosarcoma

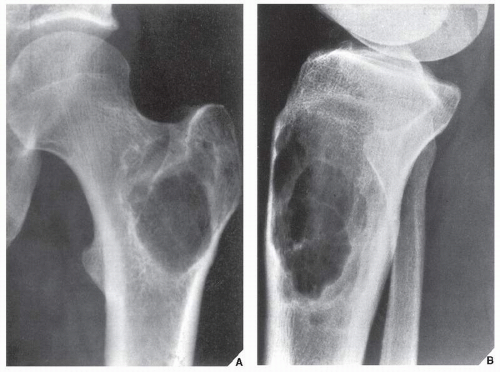

A very aggressive type of osteosarcoma, the telangiectatic variant, also called hemorrhagic osteosarcoma by Campanacci, is twice as common in males than in females and is seen predominantly in patients in their

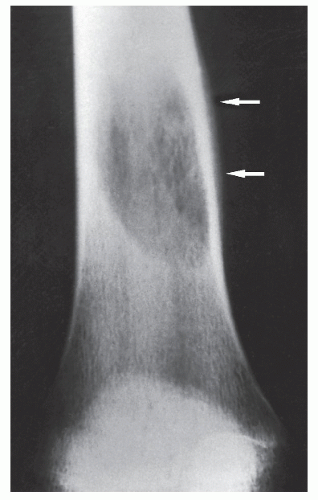

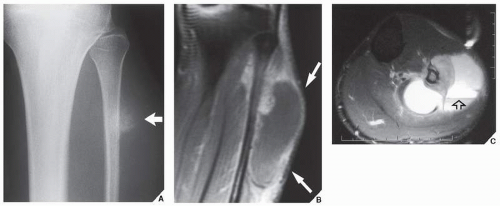

second and third decades of life. It is rare, comprising approximately 3% of all malignant bone tumors. It is characterized by a high degree of vascularity and large cystic spaces filled with blood, which account for its atypical imaging presentation. Most of these tumors arise in the femur and tibia. On radiography, telangiectatic osteosarcoma most commonly presents as an osteolytic destructive lesion with or without matrix mineralization, and with an almost complete absence of sclerotic changes; a soft-tissue mass may also be present (Figs. 21.15,21.16,21.17,21.18). An aggressive periosteal reaction (lamellar, sunburst, or Codman triangle) is present in most patients, reflecting the malignant nature of this tumor, and a pathologic fracture is not uncommon in the case of large lesions. On MRI, telangiectatic osteosarcoma often exhibits areas of high signal intensity on T1-weighted sequences, owing to the presence of methemoglobin. On T2 weighting, signal intensity is commonly heterogeneous. Fluid-fluid levels can occasionally be seen (Fig. 21.19), similar to ones seen in aneurysmal bone cyst.

second and third decades of life. It is rare, comprising approximately 3% of all malignant bone tumors. It is characterized by a high degree of vascularity and large cystic spaces filled with blood, which account for its atypical imaging presentation. Most of these tumors arise in the femur and tibia. On radiography, telangiectatic osteosarcoma most commonly presents as an osteolytic destructive lesion with or without matrix mineralization, and with an almost complete absence of sclerotic changes; a soft-tissue mass may also be present (Figs. 21.15,21.16,21.17,21.18). An aggressive periosteal reaction (lamellar, sunburst, or Codman triangle) is present in most patients, reflecting the malignant nature of this tumor, and a pathologic fracture is not uncommon in the case of large lesions. On MRI, telangiectatic osteosarcoma often exhibits areas of high signal intensity on T1-weighted sequences, owing to the presence of methemoglobin. On T2 weighting, signal intensity is commonly heterogeneous. Fluid-fluid levels can occasionally be seen (Fig. 21.19), similar to ones seen in aneurysmal bone cyst.

On gross pathologic examination, the tumor resembles a “bag” of blood and is characterized by blood-filled spaces, necrosis, and hemorrhage. Histologically, it is composed of loculated blood-filled spaces, partially lined by malignant cells producing sparse osteoid tissue. It resembles an aneurysmal bone cyst, both radiologically and pathologically.

Small Cell Osteosarcoma

Described by Sim and associates, small cell osteosarcoma with preferential sites of distal femur, proximal humerus, and proximal tibia, usually occurs as a radiolucent lesion with permeative borders and a large soft-tissue mass. Its radiographic appearance thus mimics that of a round cell bone sarcoma. These lesions usually exhibit small round cells in many histologic fields, much like Ewing sarcoma. The presence, however, of spindled tumor cells, as well as the focal production of osteoid or bone, helps to make a histologic diagnosis of osteosarcoma.

Fibrohistiocytic Osteosarcoma

Fibrohistiocytic osteosarcoma, which resembles MFH, has recently been described in the literature. It can sometimes be confused with true MFH of bone because both of these tumors tend to arise at a greater age than conventional osteosarcoma, usually after the third decade. Both tend to involve the articular ends of long bones, and less periosteal reaction is typically present than in conventional osteosarcoma. Although on radiography both of these lesions tend to be radiolucent and thus do resemble giant cell tumor and fibrosarcoma, the MFH-like osteosarcoma usually exhibits areas of bone formation resembling cotton balls or cumulus clouds, whereas MFH does not. When such areas are identified on imaging studies, a diligent search should be made for tumor bone in the resected specimen. Histologically, MFH-like osteosarcoma is characterized by pleomorphic spindle cells and giant cells, many of which have bizarre nuclei. This lesion therefore resembles giant cellrich osteosarcoma. An inflammatory background is not unusual, and the storiform or spiral nebular arrangement, characteristic of MFH, although sometimes a dominant feature, may be less prominent or may be replaced by areas of large pleomorphic cells arranged in diffuse sheets. As in all other subtypes of osteosarcoma, the distinction from other sarcomas depends on the demonstration of osteoid or bone formation by malignant cells in the very typical patterns seen in osteosarcomas.

Intracortical Osteosarcoma

Intracortical osteosarcoma is one of the rarest forms of osteosarcoma. Very few of these tumors have been reported, with an age range of 9 to 43 years (average 24 years) and a male predominance. The presenting symptom is pain, often associated with activity. In some patients, a history of previous trauma has been elicited. The tumor involves the cortex, without extension into the medullary portion of the bone or the soft tissues. The radiographic presentation is that of a radiolucent lesion with surrounding cortical sclerosis. The size of the lesion varies from 1.0 to 4.2 cm. In some instances, the lesion mimics osteoid osteoma or intracortical osteoblastoma.

Gnathic Osteosarcoma

Gnathic osteosarcoma is osteosarcoma arising in the maxilla or mandible. Unlike osteosarcoma arising elsewhere in the skeleton, this tumor occurs in older patients (fourth to sixth decades, with a mean age of 35 years). It is usually a well-differentiated tumor with a low mitotic rate, possessing a predominantly cartilaginous component in a high percentage of cases and with less malignant potential and a better prognosis than for other forms of osteosarcoma.

Multicentric (Multifocal) Osteosarcoma

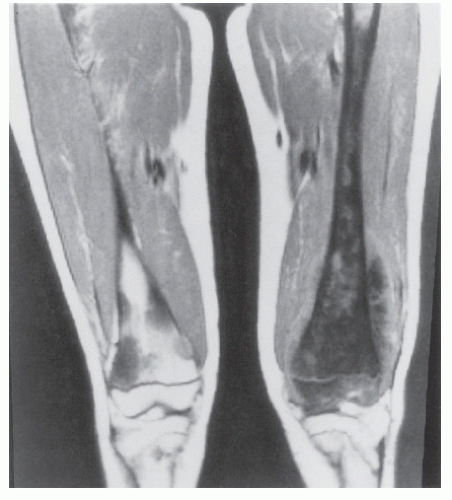

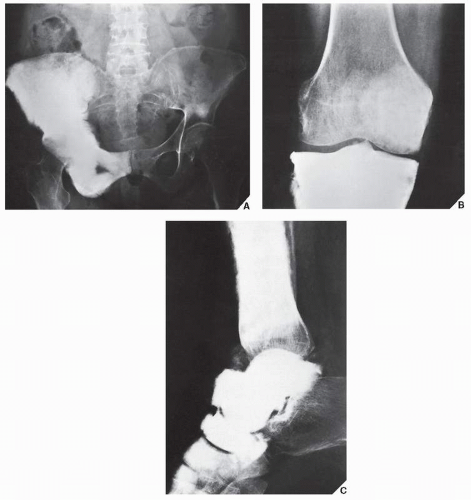

The simultaneous development of foci of osteosarcoma in multiple bones is a rare occurrence (Figs. 21.20 and 21.21). Whether this entity is truly separate or represents multiple bone metastases from a primary conventional osteosarcoma remains a controversy. This type of osteosarcoma is currently recognized as having two variants: synchronous and metachronous. Multifocal osteosarcoma must be differentiated from osteosarcoma metastasized to other bones.

Surface (Juxtacortical) Osteosarcomas

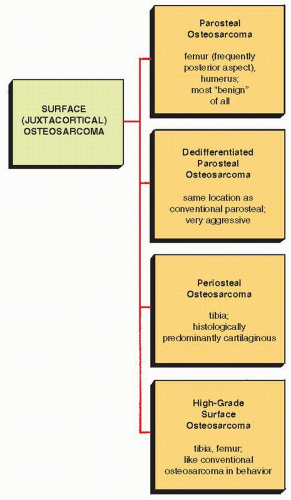

The term juxtacortical is a general designation for a group of osteosarcomas that arise on the bone surface (Fig. 21.22). Usually, these lesions are much rarer and occur a decade later than their intraosseous counterparts. The majority of juxtacortical osteosarcomas are low-grade tumors, although there are moderately and even highly malignant variants.

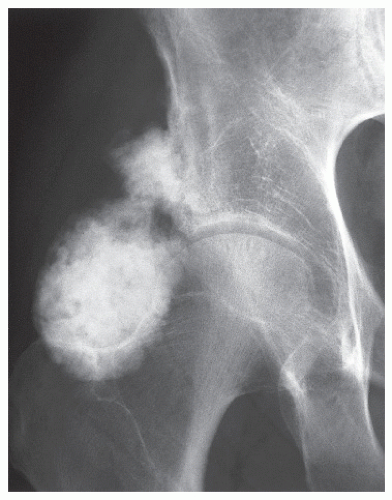

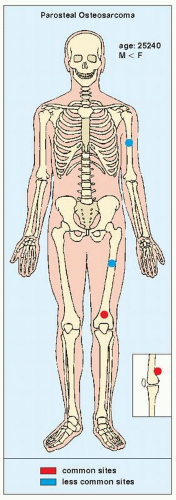

Parosteal Osteosarcoma. Parosteal tumors are seen largely in patients in their third and fourth decades, with a characteristic site of predilection in the posterior aspect of the distal femur (Fig. 21.23).

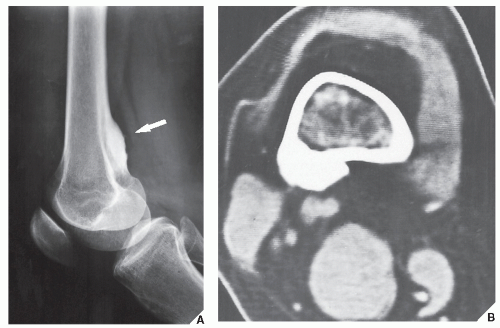

Conventional radiography is usually adequate for making a diagnosis of parosteal osteosarcoma. The lesion presents as a dense oval or spherical mass attached to the cortical surface of the bone and sharply demarcated from the surrounding soft tissues (Figs. 21.24,21.25,21.26). CT (Fig. 21.26B) or MRI (see Fig. 16.21) is often necessary to determine whether the lesion has penetrated the cortex and invaded the medullary region of the bone.

Histologically, the lesion consists of fibrous stroma, probably derived from the outer fibrous periosteal layer. The osseous component is often trabeculated but is at least partially immature, particularly at the periphery of the tumor. This is an important point in differentiating it from the sometimes similar-appearing myositis ossificans, which, however, matures in a centripetal fashion, with its most mature portion outermost.

Differential Diagnosis. Parosteal osteosarcoma must be differentiated from parosteal osteoma (see Fig. 17.4), myositis ossificans, soft-tissue osteosarcoma, parosteal liposarcoma with ossifications, and sessile osteochondroma. Differentiation from myositis ossificans and

osteochondroma is the most frequent source of confusion. Myositis ossificans is distinguished by a zonal phenomenon and by a cleft separating the ossific mass from the cortex (Fig. 21.27; see also Figs. 4.55, 4.56 and 18.28). In sessile osteochondroma, however, the cortex of the lesion merges without interruption into the cortex of the host bone (see Figs. 18.26 and 18.28), a feature not seen in parosteal osteosarcoma. Because the lesion is relatively slow growing and most often involves only the surface of the bone, the prognosis for patients with parosteal osteosarcoma is much better than for those with other types of osteosarcoma. Simple wide resection of the lesion often constitutes sufficient treatment.

osteochondroma is the most frequent source of confusion. Myositis ossificans is distinguished by a zonal phenomenon and by a cleft separating the ossific mass from the cortex (Fig. 21.27; see also Figs. 4.55, 4.56 and 18.28). In sessile osteochondroma, however, the cortex of the lesion merges without interruption into the cortex of the host bone (see Figs. 18.26 and 18.28), a feature not seen in parosteal osteosarcoma. Because the lesion is relatively slow growing and most often involves only the surface of the bone, the prognosis for patients with parosteal osteosarcoma is much better than for those with other types of osteosarcoma. Simple wide resection of the lesion often constitutes sufficient treatment.

FIGURE 21.20 Multicentric osteosarcoma. Multicentric osteosarcoma, a very rare bone tumor, is demonstrated here in the right hemipelvis (A), right tibia (B), and several bones of the right foot (C). |

FIGURE 21.23 Skeletal sites of predilection, peak age range, and male-to-female ratio in parosteal osteosarcoma. |

FIGURE 21.24 Parosteal osteosarcoma. Typical presentation of this tumor at the posterior aspect of the distal femur (arrows) in a 23-year-old woman. |

Dedifferentiated Parosteal Osteosarcoma. A rare and unusual bone tumor, dedifferentiated parosteal osteosarcoma, was identified by a group from the Mayo Clinic. Most cases reportedly originate as conventional parosteal osteosarcomas that, after resection and multiple local recurrences, have undergone transformation to histologically high-grade sarcomas. Some cases, however, have presented as primary tumors arising on the cortical surface of a bone de novo. Radiographically and histologically, dedifferentiated parosteal osteosarcoma mimics the features of conventional parosteal osteosarcoma. There are, however, some traits of a high-grade sarcoma, such as radiographically identifiable cortical destruction (Fig. 21.28) and histologically identifiable pleomorphic tumor cells with hyperchromatic nuclei and a high mitotic rate. Hence, the prognosis is much worse than that of parosteal osteosarcoma.

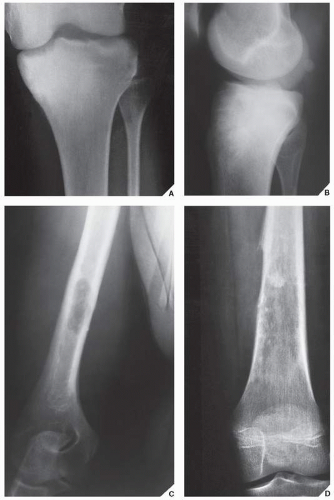

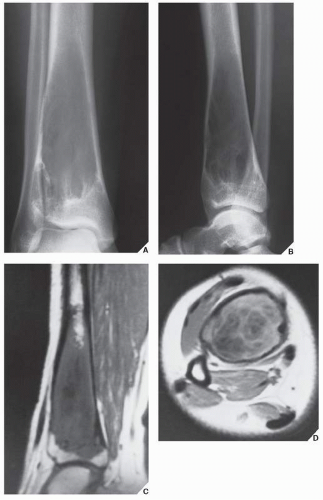

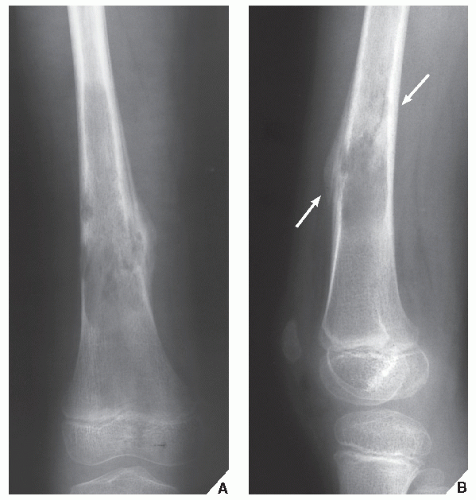

Periosteal Osteosarcoma. Most often occurring in adolescence, periosteal osteosarcoma is a very rare tumor (accounting for 1% to 2%

of all osteosarcomas) that grows on the bone surface, usually at the midshaft of a long bone such as the tibia. The characteristic feature of this tumor, which radiographically may resemble myositis ossificans, is a predominance of cartilaginous tissue (Fig. 21.29). This may lead to an erroneous diagnosis of periosteal chondrosarcoma. The radiologic characteristics of periosteal osteosarcoma were defined by deSantos and colleagues. These include a heterogenous tumor matrix with calcified spiculations interspersed with areas of radiolucency representing uncalcified matrix; occasional periosteal reaction in the form of a Codman triangle (Fig. 21.30); thickening of the periosteal surface of the cortex at the base of the lesion, with sparing of the endosteal surface; extension of the tumor into the soft tissues; and sparing of the medullary cavity (Fig. 21.31). By microscopy, these tumors have low-grade to medium-grade malignancy and are composed mainly of lobulated chondroid tissue with moderate cellularity. Periosteal osteosarcoma is marked by a better prognosis than the conventional type but a worse one than the parosteal variant.

of all osteosarcomas) that grows on the bone surface, usually at the midshaft of a long bone such as the tibia. The characteristic feature of this tumor, which radiographically may resemble myositis ossificans, is a predominance of cartilaginous tissue (Fig. 21.29). This may lead to an erroneous diagnosis of periosteal chondrosarcoma. The radiologic characteristics of periosteal osteosarcoma were defined by deSantos and colleagues. These include a heterogenous tumor matrix with calcified spiculations interspersed with areas of radiolucency representing uncalcified matrix; occasional periosteal reaction in the form of a Codman triangle (Fig. 21.30); thickening of the periosteal surface of the cortex at the base of the lesion, with sparing of the endosteal surface; extension of the tumor into the soft tissues; and sparing of the medullary cavity (Fig. 21.31). By microscopy, these tumors have low-grade to medium-grade malignancy and are composed mainly of lobulated chondroid tissue with moderate cellularity. Periosteal osteosarcoma is marked by a better prognosis than the conventional type but a worse one than the parosteal variant.

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree