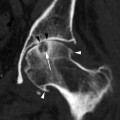

Fig. 37.1

CC (a) and MLO (b) views demonstrate a high-density lobulated mass with spiculated margins most conspicuous at its anterior edge (arrows). Pathology: Invasive ductal carcinoma

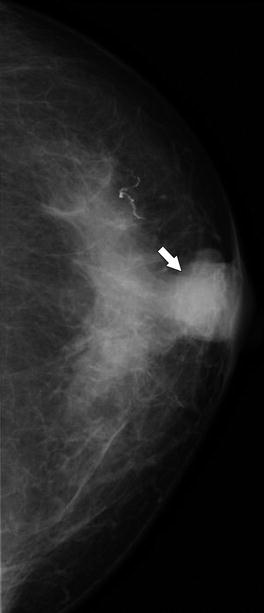

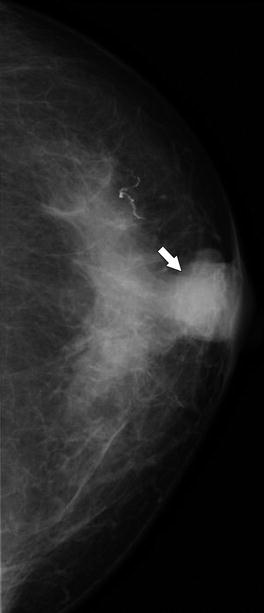

Fig. 37.2

A 71-year-old woman. MLO view demonstrates a high-density oval, relatively well-circumscribed mass (arrow). Pathology: Invasive ductal carcinoma

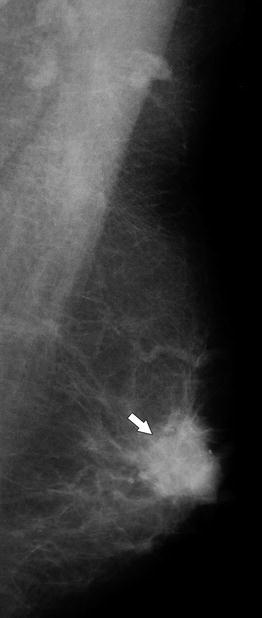

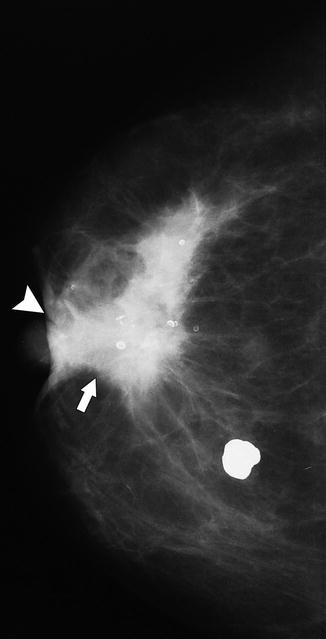

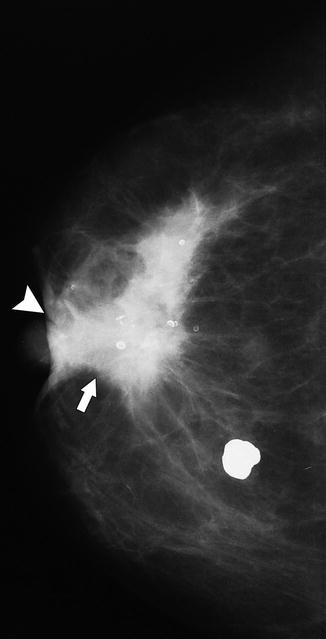

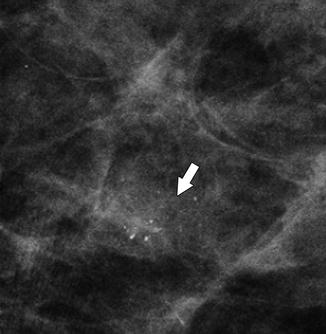

Fig. 37.3

A 67-year-old woman. MLO view demonstrates a lobulated mass with indistinct margins (arrow). Pathology: Invasive ductal carcinoma

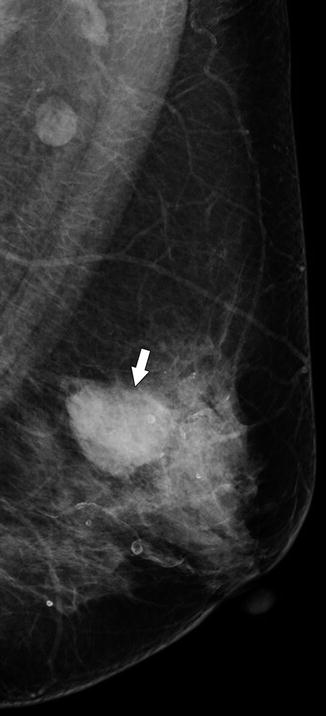

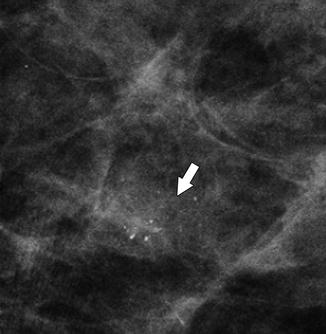

Fig. 37.4

A 78-year-old woman. CC view demonstrates a small spiculated mass (arrow) representing invasive ductal carcinoma. Heterogeneous calcifications (arrowheads) extend beyond the mass in a segmental distribution and represent DCIS

It is essential that any indeterminate mass seen on mammography be evaluated by ultrasound. Just as there are large variations in the appearance of IDCs on mammography, there are also variations in appearance on ultrasonography. Typical ultrasound findings suggestive of malignancy include hypoechogenicity compared with the surrounding normal breast fat, a taller-than-wide orientation, angular or spiculated margins, and attenuation of sound posterior to the malignancy (Stavros et al. 1995) (Fig. 37.5). However, ultrasound findings must be interpreted with caution, as there are many exceptions to these very general “rules.” Each lesion may be heterogeneous within itself, with some portions of the lesion appearing benign but with other portions of the same lesion showing more malignant-appearing features. The entire lesion must be scanned carefully for analysis. High-grade cancers can grow quickly and can be very cellular. The rapid growth of a high-grade cancer may not allow time for the formation of a fibrosing or desmoplastic reaction around the tumor, resulting in a more circumscribed appearance. Also, the high cellularity of these lesions may allow sound to be transmitted through the lesion, resulting in posterior acoustic enhancement instead of the typical shadowing often seen in malignancies. Adherence to strict interpretation criteria is necessary; otherwise, these well-circumscribed, extremely hypoechoic, and sound-transmitting malignant lesions may be misinterpreted as cysts.

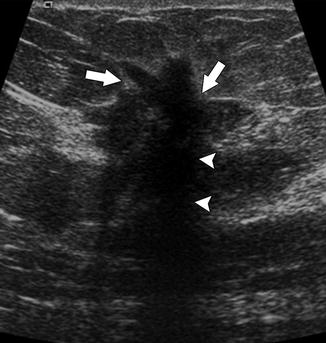

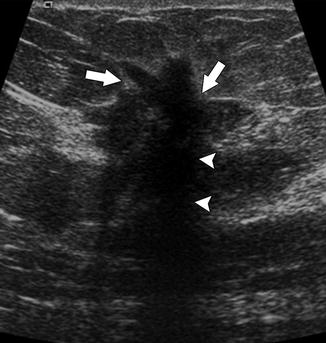

Fig. 37.5

This mass demonstrates malignant ultrasonographic features, including hypoechogenicity, angular margins (arrows), and posterior acoustic shadowing (arrowheads). Pathology: Invasive ductal carcinoma

In recent years, dynamic contrast-enhanced magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) has become an important breast imaging tool. On MRI, IDC can present as an enhancing mass or an area of non-mass-like enhancement (Bartella et al. 2006). Analysis of masses identified on MRI is based on morphologic evaluation of size, shape, and margins; evaluation of the enhancement characteristics of a mass after the administration of gadolinium-based contrast material may aid in interpretation as well. Generally speaking, altered vascular status of malignancies will allow contrast material to rapidly wash in and then back out of the cancer (Fig. 37.6), resulting in the typically malignant-appearing kinetic curve. Benign lesions tend to enhance more slowly and progressively, leading to persistent or progressive enhancement signal over time. However, it is important to note that a substantial number of malignancies may also have an indeterminate plateau-type kinetic pattern (Bartella et al. 2006) or even a progressive enhancement pattern; therefore, appropriate management cannot be based solely on kinetic evaluation. Careful evaluation of the lesion’s morphology is imperative, as is correlation with conventional imaging such as mammography and ultrasonography.

Fig. 37.6

Sagittal post-contrast T1-weighted MRI with fat suppression (a) demonstrates an irregular, heterogeneously enhancing mass (arrow). It demonstrates malignant-appearing kinetics, with greater enhancement intensity seen on the early (b) subtraction image than on the delayed (c) subtraction image, due to rapid wash-in and washout of contrast material from the mass. Pathology: Invasive ductal carcinoma

MRI may be helpful for evaluating tumor extension into the pectoralis muscle or chest wall. Other associated findings that can be seen with invasive ductal cancers may be nipple retraction, skin involvement, and regional adenopathy (Figs. 37.7, 37.8, and 37.9). Ultrasound is a valuable tool in the assessment of the regional nodal basins, including the axilla, infraclavicular, internal mammary, and supraclavicular regions.

Fig. 37.7

A 86-year-old woman. CC (a) and MLO (b) views demonstrate a high-density irregular mass (asterisk) with associated skin thickening (arrows) and overlying skin retraction (arrowhead). An involved axillary lymph node (curved arrow) is relatively small but irregular in shape; the normal morphology of the node has been lost. Pathology: Invasive ductal carcinoma with skin involvement and axillary nodal metastasis

Fig. 37.8

A 74-year-old woman. MLO view demonstrates a high-density round mass (arrow) representing invasive ductal carcinoma. A large metastatic lymph node is seen in the axilla (arrowhead)

Fig. 37.9

A 77-year-old woman. CC view shows a high-density spiculated mass (arrow), which causes tethering and retraction of the nipple (arrowhead)

37.2.2 Invasive Lobular Carcinoma

Invasive lobular carcinoma (ILC) is the second most common type of breast cancer, accounting for approximately 10 % of all breast cancers (Howlader et al. 2011). ILCs are more likely to be multiple and bilateral than are IDCs. Unfortunately, ILC is notoriously difficult to diagnose. In ILC, tumor cells are arranged in linear columns or single files of cells, and their pattern of invasion may preserve the architecture of the surrounding breast structures. Owing to this insidious pattern of spread, a well-defined tumor mass may not form or may not be evident on imaging or clinical exam. These patients often present with a vague palpable area of thickening as opposed to a discrete mass. They may complain of shrinking or retracting of the breast (Harvey et al. 2000), nipple retraction, or changes in breast contour. In patients with such symptoms, a high level of suspicion is needed, and the radiologist must search for subtle signs of malignancy.

ILC is mammographically occult more frequently than IDC is (Berg et al. 2004). When seen on mammography, ILC may appear as an irregular or spiculated density (Hilleren et al. 1991; Le Gal et al. 1992). However, even large tumors may be of relatively low density, often equal to that of normal breast parenchyma. These tumors may be seen only on one mammographic view but remain imperceptible on tangential views (Fig. 37.10). Less common findings include areas of architectural distortion, parenchymal asymmetry, or developing density (Hilleren et al. 1991; Le Gal et al. 1992) (Fig. 37.11). The breast affected by ILC may appear smaller than the contralateral breast on mammographic images or may appear to be shrinking and retracting when compared with prior mammograms (Fig. 37.12). Mammographic findings may be normal, even in patients with fatty breasts and extensive disease (Hilleren et al. 1991).

Fig. 37.10

Focal asymmetry (arrow) in the superior breast is seen on the MLO view (a) but is subtle and more difficult to perceive on the CC view (b). Circular markers in (a) and (b) are on skin moles. Ultrasonography (c) demonstrates an ill-defined area of hypoechogenicity (arrow). Final Pathology: Invasive lobular carcinoma

Fig. 37.11

MLO view (a) demonstrates a subtle area of architectural distortion (arrow), which was not seen on any other mammographic views. Ultrasonography (b) reveals a small, vertically oriented, hypoechoic mass (arrow) with irregular margins which correlates with the mammographic finding. Pathology: Invasive lobular carcinoma

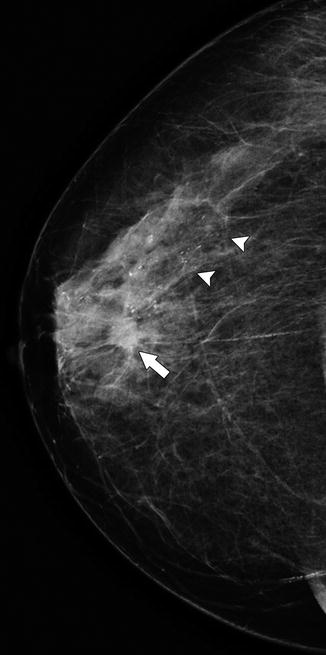

Fig. 37.12

CC (a) and MLO (b) views demonstrate the left breast to be slightly smaller than the right. There is flattening and subtle retraction of the left nipple (curved arrows). Density seen in the retroareolar position on the CC view (arrow) is not as well appreciated on the MLO view. Small focal asymmetry inferiorly on the MLO view (arrowhead) is not identified on the CC view. Pathology: Invasive lobular carcinoma involving several quadrants of the breast with 18 cm of disease

Ultrasound and MRI have a higher sensitivity for ILC than does mammography (Berg et al. 2004; Selinko et al. 2004). Ultrasound evaluation of ILC may demonstrate a hypoechoic ill-defined mass, with or without posterior acoustic shadowing. A more infiltrative appearance is sometimes seen as ill-defined areas of hypoechogenicity without identifiable margins, with or without posterior acoustic shadowing (Fig. 37.13). Shadowing may be seen as the only finding, without an associated mass (Selinko et al. 2004; Watermann et al. 2005; Lopez and Bassett 2009).

Fig. 37.13

CC (a), MLO (b), and spot compression (c, d) views demonstrate an extremely subtle area of distortion in the upper outer breast (arrows). Ultrasonography (e, f) of the same area demonstrates an ill-defined area of heterogeneous hypoechogenicity (arrow). In some areas, a “picket-fence” appearance was seen with subtle areas of vertically oriented hypoechoic shadowing (arrowheads). Pathology: Invasive lobular carcinoma

MRI may be used in patients whose clinical findings remain suspicious even after negative mammogram and ultrasound findings. A role for MRI in the preoperative evaluation of the extent of disease has been suggested for newly diagnosed ILC patients (Mann et al. 2010). On MRI, ILC may appear as an irregular mass with spiculated or ill-defined margins or as an area of non-mass-like enhancement (Bartella et al. 2006; Lopez and Bassett 2009; Le-Petross and Lane 2011). A dominant mass with surrounding smaller lesions or multiple foci with interconnecting strands may also be seen (Lopez and Bassett 2009; Le-Petross and Lane 2011). While some ILCs demonstrate typically malignant-appearing MRI kinetics with rapid influx of contrast followed by rapid washout, ILCs may do so less often than IDCs (Dietzel et al. 2010). Some ILCs may enhance more slowly and at later phases (Lopez and Bassett 2009) (Fig. 37.14). It is imperative that a lesion be managed according to its worst feature; a benign-appearing kinetic curve should not deter biopsy of an otherwise suspicious lesion.

Fig. 37.14

MLO views (a) demonstrate a large irregular mass (arrow) in the right breast with associated nipple retraction (arrowhead). Circular markers left breast are on skin moles. Ultrasonography (b) demonstrates a hypoechoic mass (arrow) with significant posterior acoustic shadowing (arrowheads). Early (c) and delayed (d) subtraction images generated from dynamic contrast-enhanced breast MRI show higher signal intensity on delayed images than on early images (arrows), suggesting that this malignancy has a progressive type enhancement pattern as opposed to the typically malignant washout type curve. Pathology: Invasive lobular carcinoma

ILC continues to be a diagnostic challenge, and physicians need to maintain a high level of awareness of the radiological and clinical signs of this disease, as findings are often extremely subtle. Biopsy of suspicious lesions should be performed using core biopsy technique. Given the incohesive growth pattern of ILC, fine-needle aspiration biopsy may not yield sufficient material for diagnosis.

37.2.3 Ductal Carcinoma In Situ

Approximately 20–30 % of breast cancers detected on mammography are ductal carcinoma in situ (DCIS) (Ernster et al. 2002; D’Orsi 2010). As in IDCs, the tumor cells of DCIS originate at or near the TDLU; however, there is no invasion through the basement membrane and DCIS lesions therefore have no metastatic potential. The sensitivity of mammography for detecting DCIS has been reported at 86 %, which is higher than mammography’s reported sensitivity for invasive cancers (Ernster et al. 2002); the implementation of widespread mammographic screening programs has resulted in higher detection and increased incidence of DCIS.

The large majority of DCIS lesions manifest as calcifications on mammography. Calcifications are assessed based on their morphology and distribution. Suspicious calcifications may have amorphous, linear, or pleomorphic morphology and may have grouped, linear, or segmental distribution (Figs. 37.15 and 37.16). High-grade DCIS can be associated with fine-pleomorphic or fine-linear branching calcifications (Barreau et al. 2005; Hofvind et al. 2011). Subtypes of DCIS differ in biological behavior and in level of aggressiveness. DCIS is a heterogeneous disease and may be classified by nuclear grade and by the presence or absence of necrosis. DCIS is a precursor to invasive disease and as such may advance to an invasive malignancy; however, 25–30 % of DCIS lesions (D’Orsi 2010) will not progress to invasive cancers and would remain clinically insignificant even if left untreated. There have been efforts to mammographically distinguish aggressive DCIS lesions from more indolent ones (Barreau et al. 2005), but the large overlap in imaging appearance makes it currently impossible to radiologically predict which DCIS lesions will progress to invasive malignancies.

Fig. 37.15

CC (a) and lateral (b) magnification views demonstrate pleomorphic calcifications with a segmental distribution (arrows). Calcifications such as these are highly suspicious for malignancy and require biopsy. Pathology: High-grade DCIS

Fig. 37.16

Magnification view demonstrates a cluster of indeterminate calcifications (arrow). Some of the calcifications appear larger and punctuate, but others are smaller and amorphous, and therefore, the entire group is accurately characterized as pleomorphic. Biopsy should be pursued. Pathology: High-grade DCIS

Although the majority of DCIS lesions result in calcifications, approximately 10–20 % of DCIS lesions are noncalcified (Cho et al. 2008). Low-grade DCIS without necrosis is more likely to be noncalcified than is higher-grade DCIS; therefore, low-grade DCIS may go undetected on mammography more frequently than high-grade DCIS (Yamada et al. 2010). Noncalcified DCIS may present as masses, asymmetries, or areas of architectural distortion, or they may remain occult on conventional imaging (Cho et al. 2008; Yamada et al. 2010). MRI can detect both calcified and noncalcified areas of DCIS. Although early MRI literature suggested that MRI sensitivity for DCIS was inadequate and was possibly lower than the sensitivity of mammography for DCIS, imaging techniques have improved over time, and as radiologists have gained more breast MRI experience, there is a better understanding of the MRI features of DCIS. Current literature reports MRI sensitivities for DCIS that are similar to or greater than those of mammography (Kuhl et al. 2007; Warner et al. 2011). The sensitivity of MRI for DCIS now approaches its sensitivity for detecting invasive cancers, which is extremely high (Kuhl et al. 2007; Warner et al. 2011). On MRI, DCIS most commonly presents as clumped non-mass-like enhancement with a ductal or segmental distribution. Kinetic evaluation of DCIS is not reliable and should be interpreted with caution; persistent, plateau, or washout curves may be seen in DCIS.

Although ultrasound does not play a large role in the evaluation of DCIS, ultrasonography may be helpful in evaluating patients with symptoms such as palpable areas of concern, nipple discharge, or nipple changes that are suspicious for possible Paget disease. Noncalcified masses or asymmetries seen on mammography should be evaluated with ultrasound as well. Ultrasound findings of DCIS may include irregular masses, often with microlobulated margins, or complex masses with both solid and cystic components. A “pseudomicrocystic” appearance may result from distension of the lobular portion of the TDLU; this appearance of DCIS may mimic a benign cluster of microcysts (Mesurolle et al. 2009). Any growth in this type of lesion, particularly in a postmenopausal patient, should prompt biopsy.

37.2.4 Papillary Carcinoma

Papillary carcinoma is an unusual malignant breast tumor, constituting about 1–2 % of all breast cancers (Soo et al. 1994). Papillary carcinoma generally occurs in women older than age 60 years (mean, 63–67 years) and usually has a good prognosis owing to a slow growth rate and less frequent axillary nodal metastasis (Liberman et al. 2001). Patients may present with a palpable mass or nipple discharge, with the latter present in 22–34 % of patients with papillary carcinoma (Soo et al. 1994). Papillary carcinoma may also be detected on screening mammography.

Papillary carcinoma can be either noninvasive or invasive and can be either solitary or multiple. Noninvasive papillary carcinoma can be either intraductal or intracystic type. When the tumor grows within a dilated duct, the lesion is classified as intraductal papillary carcinoma. If the tumor grows within a cyst, it is classified as intracystic papillary carcinoma. Invasive papillary carcinoma can spread from either the intraductal or intracystic type. The invasive component can retain a papillary pattern or, more commonly, can have various growth patterns of usual or not otherwise specified type (Ibarra 2006; Muttarak et al. 2008).

Imaging features of noninvasive and invasive papillary carcinomas overlap. On mammography, papillary carcinomas appear as a solitary round, oval, or lobulated mass with circumscribed, obscured, or indistinct margins. Another possible presentation is a cluster of well-defined masses confined to one breast quadrant. Associated microcalcifications may be present. On ultrasonography, papillary carcinomas appear as solitary or multiple circumscribed, hypoechoic masses or as complex masses with both cystic and solid components (Soo et al. 1994; Liberman et al. 2001; Muttarak et al. 2008) (Figs. 37.17 and 37.18). Intracystic papillary carcinoma may have hemorrhage within the cyst owing to torsion or hemorrhagic infarction of the tumor. Color Doppler ultrasonography is helpful to demonstrate blood flow within the tumor and differentiate tumor from blood clot.

Fig. 37.17

A 75-year-old woman. CC view (a) demonstrates a round mass with obscured margins (arrow). Ultrasonography (b) demonstrates a solid mass with relatively circumscribed margins (arrow) and subtle enhanced through transmission (arrowheads). Pathology: Invasive papillary carcinoma

Fig. 37.18

MLO view (a) demonstrates a high-density circumscribed mass (arrow). On ultrasonography (b), the mass is complex with both cystic (asterisks) and solid (arrows) components. Biopsy of a solid-appearing mural nodule should be pursued. Pathology: Intracystic invasive papillary and ductal carcinoma

37.2.5 Mucinous Breast Carcinoma

Mucinous breast carcinoma is a well-differentiated histologic subtype of invasive ductal carcinoma. This type of tumor accounts for 1–7 % of all breast cancers and usually occurs in older women (>60 years) (Cardenosa et al. 1994; Conant et al. 1994; Wilson et al. 1995; Dhillon et al. 2006). Histopathologically, mucinous carcinoma can be classified as pure or mixed form, depending on the variable mucinous content of the tumor. Pure mucinous carcinoma is characterized by all tumor cells being embedded in extracellular mucin. Mixed tumors have a more solid component comprised of infiltrating tumor cells not surrounded by mucin. It is important to distinguish pure from mixed mucinous carcinoma because the subtypes differ in behavior and prognosis. Pure mucinous carcinomas are typically less aggressive and have a lower frequency of axillary nodal metastases than do mixed mucinous carcinomas. Pure mucinous carcinoma accounts for about 7 % of breast cancers in women older than 75 years and for only 1 % in women younger than 35 years (Rosen et al. 1985).

There is good correlation between mammographic characteristics and histopathologic findings of pure and mixed mucinous carcinomas. A circumscribed mass is frequently found in pure mucinous carcinoma, whereas an indistinct, irregular mass is more commonly found in mixed mucinous carcinoma (Figs. 37.19 and 37.20). Associated calcification is more common in the mixed type than in the pure type (Wilson et al. 1995; Matsuda et al. 2000; Memis et al. 2000). A circumscribed appearance of mucinous carcinoma may mimic benign lesions and may lead to a delay in diagnosis (Dhillon et al. 2006). Therefore, mucinous carcinoma should be considered in the differential diagnosis of a circumscribed mass. On ultrasound, mucinous carcinoma may appear as a well- or poorly defined, iso- or hypoechoic, mixed solid and cystic mass, with or without posterior acoustic enhancement (Conant et al. 1994; Memis et al. 2000; Lam et al. 2004) (Figs. 37.21 and 37.22). The findings of an isoechoic mass or a homogeneous, hypoechoic mass with well-defined margins are frequently found in pure mucinous carcinoma.

Fig. 37.19

A 78-year-old woman. MLO views (a) demonstrate masses in both breasts (arrows). Pathology: Bilateral synchronous breast cancers. H&E × 100 right breast mucinous carcinoma (b) shows clusters of tumor cells (arrows) floating in a lake of mucin (m). H&E × 100 left breast invasive ductal carcinoma (c)

Fig. 37.20

A 79-year-old woman. CC view demonstrates a round mass in the subareolar position. Pathology: Invasive mucinous carcinoma

Fig. 37.21

Spot compression (a) demonstrates a small mass (arrow) which correlates with a palpable area of concern annotated by a triangular marker. On ultrasonography (b), the mass (arrow) is isoechoic to fat and circumscribed. Pathology: Invasive mucinous carcinoma

Fig. 37.22

CC (a) and MLO (b) views demonstrate a relatively circumscribed mass (arrows). On the MLO view, an enlarged lymph node is visible in the axilla (arrowhead). Ultrasonography (c) demonstrates an isoechoic mass (arrow) that correlates with the primary breast mass. Pathology: Invasive mixed mucinous carcinoma

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree