, Gustav Andreisek2 and Erika J. Ulbrich2

(1)

Phoenix Diagnostic Clinic, Cluj-Napoca, Romania

(2)

Institute of Diagnostic and Interventional Radiology, University Hospital Zürich, Zürich, Switzerland

3.1 Anatomy and Normal MRI Appearance

The medial supporting structures of the knee can be divided into three layers [1]. Layer 1 consists of the deep crural fascia that is seen on MR images as a thin low-intensity structure on all MR sequences (Fig. 3.1). Anteriorly, the deep crural fascia joins the superficial layer of MCL into the medial patellar retinaculum that appears on MR images as a low-signal-intensity structure that extends from the vastus medialis muscle to the tibia inferiorly (Fig. 3.2) [2]. In some cases, two band-like structures may be seen [2].

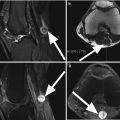

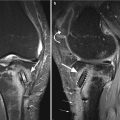

Fig. 3.1

Normal superficial layer of the medial supporting structures or layer 1 represented by deep crural fascia in a 36 year old male. Coronal proton-density (PD) FSE image (a) obtained posteriorly through the joint – the plane is drawn in c as line 3.1.A. At this level, the deep crural fascia that is seen on MR images as a thin low-intensity structure (arrows) separated by a variable amount of fat from the superficial layer of medial collateral ligament known also as the vertical part of the ligament (curved arrow). Anteriorly, mid-coronal proton-density (PD) FSE image (b) – the plane is drawn in c as line 3.1.B – the deep crural fascia (arrow) joins the medial collateral ligament (curved arrow in b)

Fig. 3.2

Normal medial retinaculum. Axial proton-density (PD) FSE fat-suppressed image shows the medial retinaculum as a thin low-signal-intensity structure (arrows) which results from the crural fascia and the superficial layer of the MCL. The medial patellar retinaculum is part of the anterior third of the medial joint capsule

The MCL is beneath the deep crural fascia (layer 1), from which it is separated by a variable amount of fat (Fig. 3.1). The MCL is composed of the superficial layer (layer 2 of the medial supporting structures) and the deep layer (layer 3 of the medial supporting structures).

The superficial layer of MCL (layer 2), also known as the vertical component of MCL, is about 12 cm long, 1–2 cm wide, and 2–4 mm thick and extends from its medial femoral epicondyle origin to its attachment at the tibial plateau, just posterior to the pes anserinus insertion (Fig. 3.1) [2]. It is the strongest part of MCL. Anteriorly, the superficial layer of MCL joins the deep crural fascia to form the medial patellar retinaculum which is part of the anterior third of the medial joint capsule (Fig. 3.2) [3]. Posteriorly, the superficial layer (layer 2) and the deep layer of MCL (layer 3) merge forming the posterior oblique portion, also known as the posterior oblique ligament (POL), that is closely attached to the posteromedial meniscus (Fig. 3.3) [4]. The posterior oblique ligament (POL) is part of the posterior third of the joint capsule and is formed by the superficial, the tibial, and the capsular arms [4]. The POL maintains medial stability and resists anteromedial tibial subluxation.

Fig. 3.3

The posterior oblique ligament (POL). Axial proton-density (PD) FSE fat-suppressed image through the meniscus shows the POL (large arrow) which results from the join of the superficial layer (layer 2) and the deep layer of medial collateral ligament (layer 3). Proximally, POL inserts at the semimembranosus tendon (small arrow). The POL is part of the posterior joint capsule and is closely attached to the medial meniscus (star)

All the above-described structures are structures of the so-called posteromedial corner. The posteromedial corner of the knee is reinforced by the semimembranosus tendon and the medial head of the gastrocnemius muscle (Fig. 3.4) [5].

Fig. 3.4

The main structures of the posteromedial corner of the knee. Axial proton-density (PD) FSE fat-suppressed image through the meniscus shows the MCL and the semimembranosus tendon (SM). The posteromedial corner is reinforced by the medial gastrocnemius tendon (MGT). The semitendinosus tendon (ST) is identified posteriorly

Layer 2 or the superficial layer of MCL appears on MR images as a homogeneous low-signal band and is separated from layer 3 or the deep layer of MCL by a variable amount of fat and the MCL bursa (Fig. 3.5). The MCL bursa is not apparent on normal MR images but may be outlined on MR images in the cases of bursitis [6].

Fig. 3.5

The two layers of the MCL. Coronal proton-density (PD) FSE image shows the superficial layer of MCL or layer 2 (large arrow) separated from layer 3 or the deep layer of MCL (small arrow) by a variable amount of fat (curved arrow)

The deep layer of the MCL (layer 3 of the medial supporting structures) is located close to the meniscus and represents the middle third of the deepest capsular layer of the knee. The medial meniscus is closely related to this layer. The deep layer of MCL includes the meniscofemoral ligament, meniscotibial ligament, and patellomeniscal ligament (Fig. 3.6). The meniscofemoral ligament originates from the superior margin of the meniscus and inserts on the femoral condyle or the superficial layer of MCL 1–2 cm above the joint line (Fig. 3.6) [2]. The meniscotibial ligament is shorter, and it extends from the inferior margin of the meniscus to tibial cortex inferior to the joint line (Fig. 3.6) [2]. The patellomeniscal ligament is seen anteriorly and extends from the medial meniscus to the patellar margin (Fig. 3.7) [7]. Anteriorly, the deep layer is continuous with the capsule of the suprapatellar recess [2]. The meniscofemoral, the meniscotibial, and the patellomeniscal ligaments are seen as thin low-signal-intensity bands on all MRI sequences (Figs. 3.6 and 3.7). The outer margin of the medial meniscus can typically not be distinguished from the deep layer of the MCL on MR images (Fig. 3.8).

Fig. 3.6

The meniscofemoral and the meniscotibial ligaments. Coronal proton-density (PD) FSE images through the anterior (a), mid-coronal (b), and posterior (c) joints. The superficial layer of the medial collateral ligament (Sup) is clearly separated by the meniscofemoral ligament which originates from the femoral condyle (MFL) and the meniscotibial ligament (MTL) which is shorter, and it extends from the inferior margin of the meniscus to tibial cortex inferior to the joint line

Fig. 3.7

The patellomeniscal ligament. Axial proton-density (PD) FSE fat-suppressed image through the meniscus shows the origin of the patellomeniscal ligament (arrow) extending anteriorly from the medial meniscus (star)

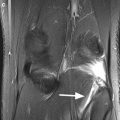

Fig. 3.8

Coronal proton-density (PD) FSE image demonstrates that the outer margin of the medial meniscus cannot be typically distinguished from the deep layer of MCL (large arrow) in comparison with the lateral side where is a clear demarcation between the lateral meniscus and the lateral collateral ligament (small arrow)

The MCL provides primary valgus stability. A secondary function of the MCL is resistance to anterior and posterior stress, supplementing the primary function of the cruciate ligaments, and therefore, in cases with ACL tears, the MCL and the medial supporting structures function as secondary restraints to anterior tibial translation [8–10].

3.2 MRI Pathological Findings

3.2.1 Acute Tear

The MCL is the most frequently injured knee ligament. Although, the treatment of the injuries is mostly nonoperatively, MR imaging is unavoidable in managing the patients. The interest in classifying the MCL injuries has declined since the treatment moves toward conservative approach for all grades of isolated injuries [11]. The MCL injuries may be classified into isolated or combined injuries. The most frequently associated lesions are ACL tears, medial meniscal lesions, meniscocapsular separations, medial retinaculum teas, disruption of the posteromedial joint capsule, and tears of pes anserinus [12].

Commonly, the MCL injuries are classified into the following three types or grades: sprain, partial tear, and complete tear.

Sprain with Intact Fibers

A MCL sprain with intact fibers is referred to as grade I MCL tear. It corresponds to ligamentous fibers that are stretched but still in continuity [12]. A MCL sprain is typically associated with pain but not with medial laxity on physical examination. The treatment is nonoperative. On MR images, the ligament is of almost normal thickness, and a diffuse edema or hemorrhage of high signal intensity on T2-weighted images parallel to superficial layer of MCL is seen (Fig. 3.9). There is a loss of clear demarcation between the MCL and the subcutaneous fat, but the ligament is still closely attached to the femoral and tibial bone at its origin and insertion, respectively (Fig. 3.9).

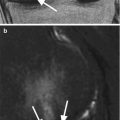

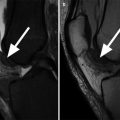

Fig. 3.9

Sprain of the medial collateral ligament (MCL) or grade I tear in a 36 year old female. Coronal proton-density (PD) fat-suppressed image (a) and axial proton-density (PD) FSE fat-suppressed image (b) show diffuse edema and hemorrhage of high signal intensity parallel to the medial collateral ligament (small arrows in a and b). The ligament fibers are intact (large arrow), and the ligament is still closely attached to the femoral and tibial bone as well as to the medial meniscus

Partial (or Incomplete) Tear

A partial tear of the MCL is referred to as grade II MCL tear. It implies an incomplete disruption of the fibers and some form of laxity on physical examination. An incomplete tear of the MCL is usually treated conservatively. MR images show a poorly defined internal signal intensity and morphologic disruption with focal abnormalities of hyperintensity of some but not all fibers [13]. The fibers are displaced from the adjacent bone at the ligaments origin or insertion, and diffuse edema and hemorrhage of high signal intensity is seen superficially and deeply to the MCL (Fig. 3.10). When the inner fibers are involved, the MCL bursa may be separated from the joint with fluid in the bursa [13]. Partial MCL tears may involve both, the superficial and the deep layer of MCL, with tear of the meniscofemoral and/or meniscotibial ligaments (Fig. 3.11). The latter two can also be affected in rare cases in isolation with an otherwise intact superficial portion of the MCL (Figs. 3.10 and 3.11). Contusion edema of the medial femoral condyle may be seen as an associated finding in partial tears of MCL. It might be noted that some authors use the expression “low-grade” and “high-grade” partial tears to address cases where partial tearing involves only few fibers or many fibers of the MCL. This is however of little consequence for patient management.