George M. Bridgeforth and Mark Nolden

A 64-year-old woman who has had a lump in her right breast for 11 years presents after falling badly and lying on the floor for several days.

CLINICAL POINTS

- Affected patients are usually older than 50 years of age.

- Patients frequently complain of extreme pain.

- A history of associated trauma may be present.

Clinical Presentation

Approximately 50% to 80% of all skeletal metastases are caused by breast, prostrate, lung, and prostrate cancers. In addition, renal cancer, gastrointestinal cancer, thyroid cancer, sarcoma, lymphoreticular malignancies, lymphoma, multiple myeloma, and melanoma also metastasize. Metastatic cancer frequently affects bones. The most common site is the spine, although the pelvis, femur, humerus, and skull are often affected. Patients may complain of pain and soreness in the lower back, pelvis, or hips (cervical metastatic disease is uncommon); limited range of motion; and weakness and weight loss. They may attribute these symptoms to recent strain or trauma. Those with skeletal metastatic lesions may develop pathologic fractures of the spine, femur, and hip.

Physical assessment of patients with metastatic spine disease can be perplexing. It requires a high index of suspicion. Key clues include a patient history of cancer (especially breast, lung, or prostrate), a positive history of smoking (especially in lung or renal cancer), hematuria (renal cancer), or a positive family history of cancer. Other key clues include undiagnosed breast masses, generalized unexplained weakness or weight loss, and sudden onset of severe low back pain with or without the sudden onset of radicular symptoms (e.g., numbness and weakness of the lower extremities).

It is important to note that metastatic cancers may also cause cauda equina injuries to the spinal cord. Affected patients usually present with severe low back pain associated with numbness and weakness of the lower extremities. In addition, they may have new problems with bowel and bladder incontinence and report changes in sexual function, including impotence and loss of libido.

PATIENT ASSESSMENT

- Patient (or family) history of cancer

- Pain and soreness

- Constitutional signs such as malaise, weakness, and weight loss

- Possible focal tenderness

The possibility of a cauda equina injury should be considered, especially if the neurological examination shows saddle anesthesia (S2, S3, S4) at the perianal region. Rectal examination reveals a loss of sphincter tone. Additional neurological findings include new-onset sensory loss, the pattern of which may vary with the type and the location of the spinal core injury. The sensory loss is associated with upper/lower motor signs (e.g., motor weakness with hyperactive or absent reflexes).

Radiographic Evaluation

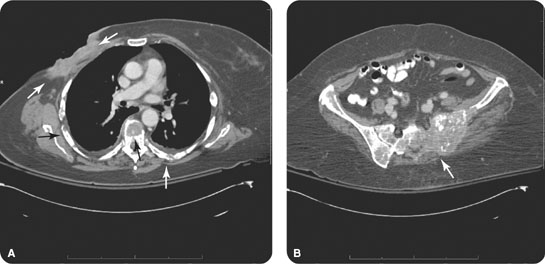

Tests to order include radiographs of the lumbar spine, including anteroposterior, lateral, and oblique views (2). Other recommended imaging tests include a magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) scan if metastatic disease is suspected. A computed tomography (CT) scan (Fig. 49.1) is optional, although if there is a high index of suspicion, a CT with narrow cuts for bone metastasis may be warranted (especially in the hospital setting where the presence of medical equipment may make it difficult to obtain an MRI scan).

It is important to note that not every injury that patients believe is associated with trauma is actually trauma related. When screening back pelvic and hip radiographs (especially in patients with severe pain over fifty years of age), it is always important to check for metastatic cancers. When viewing the anteroposterior lumbar sacral spine, a solitary metastatic lesion may be very subtle. The examiner should always check each pedicle, the ilium, the sacroiliac joints, and the sacrum for lytic or blastic changes. Lytic lesions may be produced by multiple myeloma and by lung, colon, renal, and thyroid cancers. The well-circumscribed punched-out lesions of multiple myeloma are usually apparent on skull films as well. Blastic lesions are caused by metastatic prostrate cancers. Mixed blastic/lytic lesions may be caused by breast and lung tumors as well as by cervical, testicular, and ovarian cancers, although these reproductive cancers are uncommon.

Metastatic lesions should not be confused with osteomyelitis. The following radiological clues may be helpful. Metastatic lesions (whether blastic or lytic) are usually confined to the bony architecture. For example, metastatic lesions involving two adjacent lumbar vertebral bodies shows no evidence of an inflammatory reaction that has spread across the disc space. The lesions are localized to the bony architecture. On the other hand, osteomyelitis has indistinct cortical margins with a white inflammatory reaction that has spread beyond the bones, causing a partial or complete effacement of the disc space. In the absence of widespread disease, metastatic lesions rarely affect the thoracic and cervical spine. The initial metastatic lesions are usually the lower thoracic or lumbar spine, hips, and pelvis. Although thoracic osteomyelitis is extremely rare, a patient who presents with this disease, which is characterized by indistinct inflammation and bony destructions, should be evaluated for Pott’s disease, or tuberculosis of the spine. Untreated, Pott’s disease can lead to marked unstable kyphotic deformity.

FIGURE 49.1 (A) An axial computed tomography (CT) image from the patient in the introductory case demonstrating an extensive, infiltrative lesion in the right breast with osseous involvement of the spine and ribs. (B) A more inferior CT image through the sacroiliac joints demonstrates multiple lytic soft tissue lesions.

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree