Type of Arthritis |

Site |

Crucial Abnormalities |

Technique/Projection |

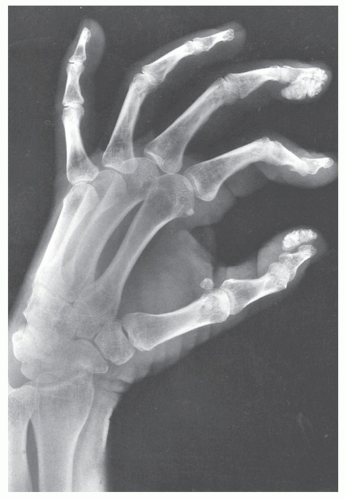

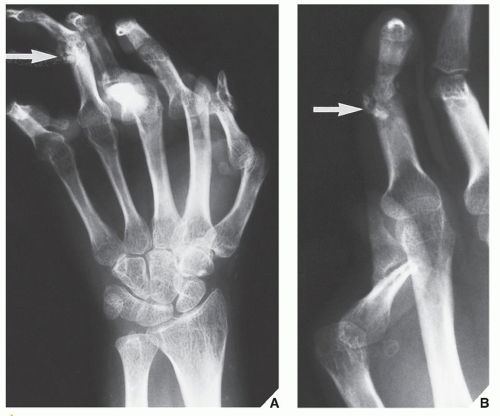

Gout (M > F) |

Great toe

Large joints (knee, elbow)

Hand |

Articular erosion with preservation of part of joint

Overhanging edge of erosion

Lack of osteoporosis

Periarticular swelling |

Standard views of affected joints |

|

|

Tophi |

Dual-energy color-coded CT |

CPPD crystal deposition disease (M = F) |

Variable joints |

Chondrocalcinosis (calcification of articular cartilage and menisci)

Calcifications of tendons, ligaments, and capsule |

Standard views of affected joints |

|

Femoropatellar joint |

Joint space narrowing

Subchondral sclerosis

Osteophytes |

Lateral (knee) and axial (patella) views |

|

Wrists, elbows, shoulders, ankles |

Degenerative changes with chondrocalcinosis |

Standard views of affected joints |

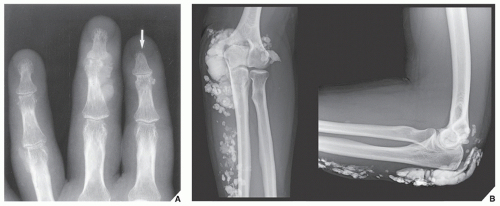

CHA crystal deposition disease (F > M) |

Variable joints, but predilection for shoulder joint (supraspinatus tendon) |

Pericapsular calcifications

Calcifications of tendons |

Standard views of affected joints |

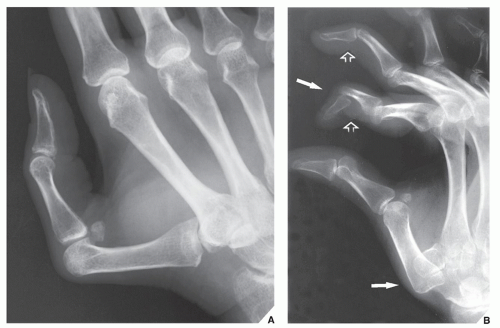

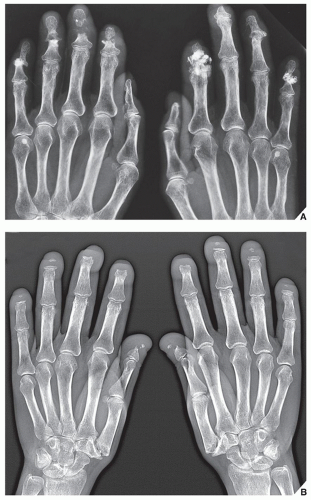

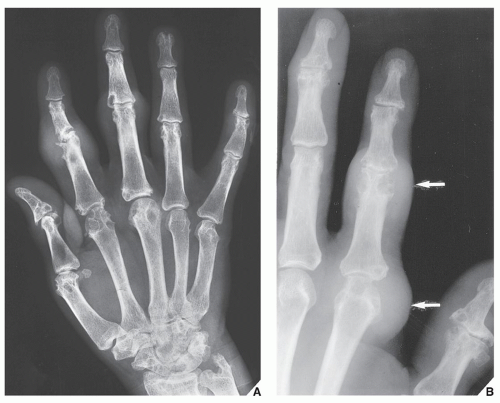

Hemochromatosis (M > F) |

Hands |

Involvement of second and third metacarpophalangeal joints with beak-like osteophytes |

Dorsovolar view |

|

Large joints |

Chondrocalcinosis |

Standard views of affected joints |

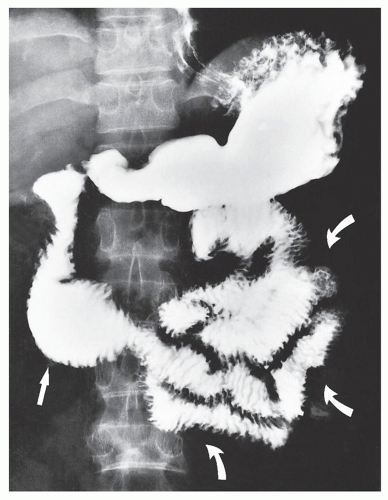

Alkaptonuria (ochronosis) (M = F) |

Intervertebral disks, sacroiliac joints, symphysis pubis, large joints (knees, hips) |

Calcification and ossification of intervertebral disks, narrowing of disks, osteoporosis, joint space narrowing, periarticular sclerosis |

Anteroposterior and lateral views of spine; standard views of affected joints |

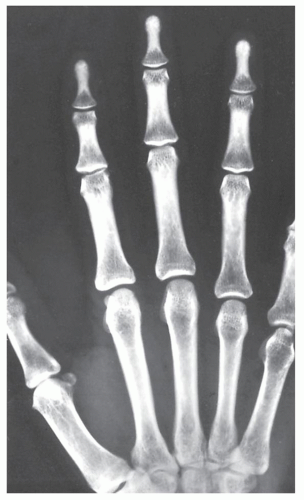

Hyperparathyroidism (F > M) |

Hands |

Destructive changes in interphalangeal joints

Subperiosteal resorption |

Dorsovolar view

Dorsovolar and oblique views |

|

Multiple bones

Skull

Spine |

Bone cysts (brown tumors)

Salt-and-pepper appearance

Rugger-jersey appearance |

Standard views specific for locations

Lateral view

Lateral view |

Acromegaly (M > F) |

Hands |

Widened joint spaces

Large sesamoid

Degenerative changes (beak-like osteophytes) |

Dorsovolar view |

|

Skull

Facial bones

Heel

Spine |

Large sinuses

Large mandible (prognathism)

Thick heel pad (>25 mm)

Thoracic kyphosis |

Lateral view

Lateral view

Lateral view

Lateral view (thoracic spine) |

Amyloidosis (M > F) |

Large joints (hips, knees, shoulders, elbows) |

Articular and periarticular erosions, osteoporosis (periarticular), joint subluxations, pathologic fractures |

Standard views of affected joints

Radionuclide bone scan (scintigraphy) |

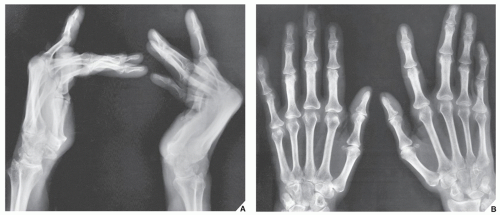

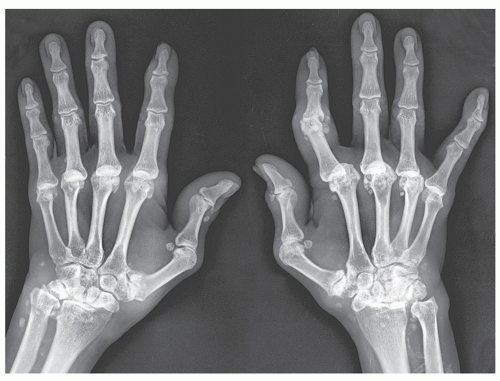

Multicentric reticulohistiocytosis (F > M) |

Hands (distal and proximal interphalangeal joints)

Feet |

Soft-tissue swelling, articular erosions, lack of osteoporosis |

Dorsovolar view

Norgaard (ball-catcher’s) view

Dorsoplantar view

Oblique view |

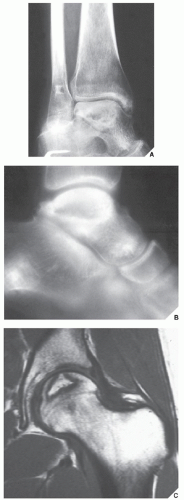

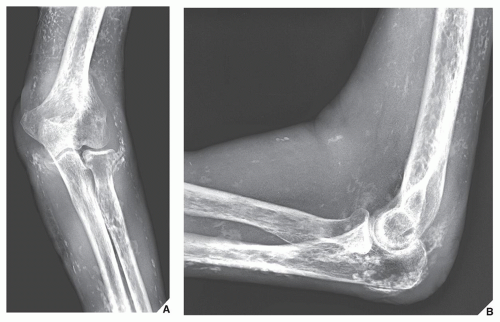

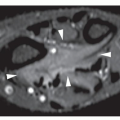

Hemophilia (M > F) |

Large joints (hips, knees, shoulders)

Elbows, ankles |

Joint effusion, osteoporosis, symmetrical and concentric joint space narrowing, articular erosions, widening of intercondylar notch, squaring of patella; very similar to changes of juvenile rheumatoid arthritis |

Standard views of affected joints

MRI |

M, male; F, female; CT, computed tomography; CPPD, calcium pyrophosphate dihydrate; CHA, calcium hydroxyapatite; MRI, magnetic resonance imaging. |