Imaging Techniques

Radiography

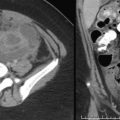

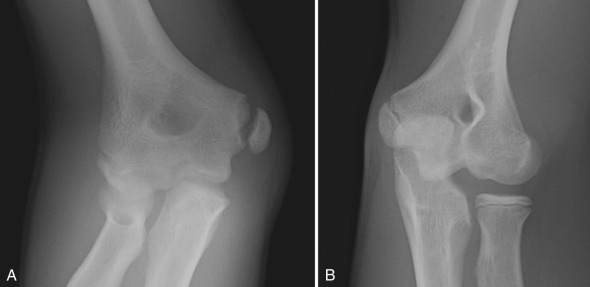

Conventional radiographs depict the bony detail of the skeletal system quite well and remain the mainstay in the evaluation of musculoskeletal disease. In the setting of acute trauma, radiographic views of the long bones are obtained in at least two projections, whereas joints are typically imaged in at least three projections. When bony injury to a digit is suspected, dedicated views of the digit alone should be obtained rather than views of the entire hand or foot. On occasion, comparison views with the contralateral asymptomatic side are useful, particularly when it is difficult to discern a suspected injury from a normal finding or normal variant. This may be helpful in the evaluation of the developing elbow in the setting of trauma, when patterns of apophyseal ossification and fusion may be confusing [ Fig. 7.1 ]. Complete radiographic skeletal surveys are indicated in the workup of suspected child abuse in infants and small toddlers. In this setting, imaging is performed on a high detail system to demonstrate subtle injuries characteristic of abuse to best advantage.

Radiographs should first be obtained in the setting of suspected infection, although they may be negative early on. It is important to exclude the presence of other pathology that may be responsible for a patient’s presenting symptoms, such as an underlying fracture or a primary osseous lesion.

Radiographs are essential in the evaluation of benign and malignant bone lesions. Although cross-sectional imaging is important in the diagnostic workup for many lesions, radiographic features are often more specific and helpful in narrowing differential diagnostic considerations. Radiographs are also helpful in planning advanced imaging once a lesion is identified.

Skeletal surveys are performed in the evaluation for dysplasia and in the assessment for multifocal bone disease seen with entities such as Langerhans cell histiocytosis (LCH). For these indications, a standard imaging system is typically used.

Ultrasound

Ultrasound has several applications in pediatric musculoskeletal imaging. It is the primary modality used in the evaluation for developmental dysplasia of the hip (DDH) from the newborn period until approximately 4 to 6 months of age, prior to ossification of the cartilaginous capital femoral epiphyses. It is used as a screening tool in infants with risk factors for DDH and also to monitor response to treatment once a diagnosis of DDH has been made.

In some centers, ultrasound is used to evaluate glenohumeral dysplasia in patients with a history of brachial plexus birth injury. The relationship of the humeral head to the glenoid can be assessed, and the angle of glenoid version can be calculated from ultrasound images.

Sonography is an effective tool in the evaluation of superficial soft tissue masses. Many common superficial lesions with characteristic sonographic features may be diagnosed by ultrasound alone. These include infantile hemangiomas, ganglion cysts, normal and abnormal lymph nodes, and popliteal cysts, among others [ Fig. 7.2 ]. When a specific diagnosis cannot confidently be made, ultrasound is helpful in stratifying lesions into those that can be clinically followed, those that require short-term ultrasound follow-up, those that might be further characterized by computed tomography (CT) or magnetic resonance imaging (MRI), and those that warrant surgical excision or biopsy.

Ultrasound is frequently used to evaluate for a joint effusion in the setting of suspected infectious or inflammatory disease. If an effusion is identified and the cause is unclear, joint fluid may be sampled under sonographic guidance.

Computed Tomography

CT remains an important modality in the evaluation of the musculoskeletal system. Scan times are very short, allowing most examinations to be completed without the need for sedation or anesthesia. Low-dose protocols are now standard for many musculoskeletal applications. The capacity for reformatting and three-dimensional reconstruction is a major advantage and is often important in guiding surgical management.

CT is particularly useful in the setting of trauma when radiographic evaluation is believed to be inconclusive or incomplete. Subtle injuries such as nondisplaced fractures of the scaphoid bone may be challenging to detect on radiographs, but well demonstrated on CT. Intraarticular extension of injuries may be shown to best advantage, and intraarticular fragments not seen on radiographs may be well demonstrated on CT. Complex injuries that may require surgical management are well profiled, including the distal tibial triplane and Tillaux fractures. CT is often useful in assessing fracture complications, including nonunion and premature physeal fusion after injury to the growth plate. Potential sternoclavicular joint injury is well assessed with CT. The sternoclavicular joints can be evaluated for symmetry, and injury to subjacent mediastinal structures can be detected in the setting of subluxation/dislocation.

Although MRI is often the advanced imaging modality of choice for assessment of a bone lesion after identification on radiographs, certain lesions have a very characteristic CT appearance, which is helpful when there is diagnostic confusion. An example is the cortically based osteoid osteoma. The MRI appearance of this lesion may be misleading. The lesion itself is typically small and may be difficult to discern, and there is often significant surrounding marrow edema and possibly synovitis involving a neighboring joint. Although these MRI features may be puzzling, a CT scan will demonstrate the classic appearance of this lesion and is most often diagnostic [ Fig. 7.3 ].

CT is helpful in the assessment for congenital anomalies such as tarsal coalition. Coalition is sometimes radiographically evident, although the diagnosis is not always clear without cross-sectional imaging. Osseous coalition is well demonstrated on CT, and fibrous and cartilaginous coalitions are typically also evident.

CT is routinely used in the evaluation of alignment disorders, including abnormalities of femoral version and tibial torsion. Glenohumeral dysplasia related to brachial plexus birth injury and patellofemoral tracking disorders also may be evaluated with CT. Multiplanar reformatting capabilities are particularly helpful for these indications, allowing quantitative measurements to be made that are useful in surgical planning.

Magnetic Resonance Imaging

There has been tremendous growth in the use of MRI in the pediatric population. Major applications include the imaging of infectious, inflammatory, neoplastic, metabolic, and sports-related pathology. Generally speaking, most children younger than 8 years require sedation or anesthesia to complete an MRI, which is managed by a dedicated team of sedation nurses and anesthesiologists (see Chapter 1 ).

Sequences used are tailored for the specific examination indication. A T1-weighted sequence is optimal for evaluation of the marrow and is particularly important in oncologic and metabolic imaging. Both T1-weighted and proton density sequences are useful for assessing trabecular architecture and demonstrating fractures to best advantage. Ligamentous anatomy, articular cartilage, and labra are well seen on proton density images.

Fluid-sensitive sequences include proton density with fat saturation, T2 with fat saturation, and short tau inversion recovery (STIR). These sequences are important in all musculoskeletal imaging, with marrow and soft tissue edema, myotendinous and ligamentous abnormality, and cartilage pathology all well demonstrated.

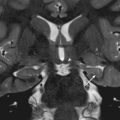

A gradient echo sequence is added to some protocols. This is useful to evaluate for anything that might cause susceptibility artifact, including blood products and intraarticular loose bodies. An example is the assessment for pigmented villonodular synovitis (PVNS). With this entity, there is often hemosiderin deposition in the synovium and joint space, with related blooming artifact demonstrated [ Fig. 7.4 ].

Postcontrast imaging is important in several settings. It is routine in the initial evaluation of bone and soft tissue tumors, and also is important in follow-up to assess for residual or recurrent disease. Postcontrast imaging is standard in the workup of suspected musculoskeletal infection. Joint involvement and intraosseous, subperiosteal, and soft tissue abscesses are well demonstrated on postcontrast images, and MRI findings are used to guide medical and/or surgical management in this setting. Inflammatory joint disease is also well profiled on contrast-enhanced imaging, with abnormal synovial thickening and hyperemia noted at the affected joint(s).

Nuclear Imaging

With improvements in the diagnostic accuracy of CT and MRI for many musculoskeletal imaging applications, utilization of nuclear imaging has decreased. It remains a useful modality in certain clinical settings, including the evaluation for very early osteomyelitis and radiographically occult bony injury. Skeletal scintigraphy is primarily performed with technetium-99m methylene diphosphonate, a pharmaceutical agent that concentrates in regions of increased blood flow and bone turnover. Sensitivity of scintigraphy with this agent is higher than that for radiography in the evaluation of pathology with osteoblastic activity, including infection, trauma, and neoplasia. Importantly, images obtained are nonspecific and do not provide anatomic detail.

Positron emission tomography (PET) imaging with fluorine-18-deoxyglucose offers high sensitivity for the detection of aggressive bone tumors, and also is useful in monitoring response to therapy. Fusion with CT or MRI improves spatial localization and allows for better characterization of lesions.

Anatomy

The tubular bones of the extremities are composed of four parts: the diaphysis; metaphysis; epiphysis; and physis, or growth plate [ Fig. 7.5 ]. Long, tubular bones have a physis at each end, whereas short tubular bones like the metacarpals and metatarsals have a physis at one end only. Generally, this is at the end of greater joint motion. The physis is composed of four layers of cartilage arranged in an organized fashion, and it is the site of long bone growth by endochondral ossification [ Fig. 7.6 ]. The physis is the weakest part of a long bone in a skeletally immature child, and thus is prone to mechanical failure and fracture.

An apophysis is an ossification center at a site where a tendon inserts. It does not contribute to the longitudinal growth of bone and does not form an articular surface [ Fig. 7.7 ]. Similar to physes, apophyses are points of relative weakness in the developing musculoskeletal system. Apophyseal injuries are relatively common in older children and adolescents, and are commonly seen involving the pelvis.

Normal Variants

Physiologic Subperiosteal New Bone Formation

Subperiosteal new bone formation may be seen as a normal finding in about 50% of infants younger than 6 months of age. In this setting, new bone is thin (≤2 mm) and smooth, and parallels the diaphysis of long bones such as the humerus, radius, femur, and tibia [ Fig. 7.8 ]. It is typically bilateral and symmetric. This finding disappears over the first weeks to months of life. There is a broad differential diagnosis for the finding of periosteal new bone formation in an infant [ Box 7.1 ].

Physiologic new bone formation

Caffey disease (infantile cortical hyperostosis)

Hypervitaminosis A

Prostaglandin therapy

TORCH (toxoplasmosis, other [congenital syphilis and viruses], rubella, cytomegalovirus, and herpes simplex virus) infections

Metastatic neuroblastoma

Child abuse

Physiologic Sclerosis

In children younger than 6 years, physiologic sclerosis may be seen along the zone of provisional calcification (ZPC) at the metaphyses of rapidly growing bones such as the femur and tibia [ Fig. 7.9A ]. These sclerotic metaphyseal bands may be difficult to distinguish from the “lead lines” seen in the setting of heavy metal intoxication. Lead lines are typically relatively broader, and are also seen in the metaphyses of more slowly growing bones such as the fibula [ Fig. 7.9B ].

Growth Recovery Lines

In the setting of stress, blood flow at the metaphysis of a long bone may be temporarily slowed and diverted. This can occur in a variety of settings, including prematurity, congenital heart disease, and trauma. Mineralization is disrupted, and a lucent band develops along the metaphysis [ Fig. 7.10A ]. When stress is relieved and bone growth resumes, a growth recovery line of Park will be seen as a curvilinear band of sclerosis at the metaphysis [ Fig. 7.10B ]. Over time this will migrate into the metadiaphysis and diaphysis, and fade into normal mineralization over months to years.

Epiphyseal Variants

Ivory epiphyses are sclerotic-appearing epiphyses most commonly seen in the distal phalanges and occasionally in the middle phalanges. This is often noted at the fifth digit [ Fig. 7.11A ]. This finding is seen in 1 in 300 children. Cone-shaped epiphyses are most commonly seen in the distal phalanges [ Fig. 7.11B ]. They may be a normal finding in 5% to 10% of children. When multiple, they may be associated with osteochondrodysplasias such as achondroplasia, Ellis–van Creveld syndrome, and cleidocranial dysostosis. They may also be associated with metabolic bone disease. Pseudoepiphyses may be seen in the proximal aspect of the second through fifth metacarpals and metatarsals or distal aspect of the first metacarpals and metatarsals [ Fig. 7.11C ]. These form by 4 to 5 years of age and fuse with the underlying bony shaft at the time of skeletal maturation. Histologically, a true physis is not identified, and pseudoepiphyses contribute little or nothing to linear growth. They are more commonly seen in children with hypothyroidism and cleidocranial dysostosis. Epiphyseal clefts or fissures may be seen, most commonly in the great toe, and should not be mistaken for fracture [ Fig. 7.11D ].

Metaphyseal Variants

Metaphyseal irregularity is commonly seen in the bones of the knee and wrist. A metaphyseal step-off, spur, or “beak” may be noted [ Fig. 7.12 ]. It is important to recognize these variants and be able to distinguish them from the classic metaphyseal lesions or bucket handle fractures seen in infants in the setting of child abuse.

Apophyseal Variants

The apophyses of the developing skeleton can have a widely varied appearance, and apophyseal irregularity is common. The apophysis at the fifth metatarsal base is a common source of confusion. This apophysis first appears during puberty. It may be in close approximation to the parent bone, or it may be somewhat distracted in the normal setting. A normal apophysis may be bifid or even somewhat fragmented. Attention to the surrounding soft tissues and correlation with focal symptoms and physical examination findings are important for diagnostic accuracy [ Fig. 7.13 ].

The calcaneal apophysis first appears around 7 years of age. It forms from the coalescence of multiple ossifications centers which fuse in the teenage years. Before fusion with the body of the calcaneus, the normal apophysis may be quite fragmented and sclerotic [ Fig. 7.14 ]. This appearance sometimes raises concern for calcaneal apophysitis, or Sever disease. This diagnosis is best made on clinical grounds rather than radiographic findings. MRI may be supportive, demonstrating apophyseal edema.

Irregular Ossification

Ossification of cartilage is not a smooth, uninterrupted process; thus irregular ossification patterns are common. This is classically seen in the epiphysis of the distal femur in younger children. Rapid growth and ossification of this epiphysis typically occurs in children between 2 and 6 years of age. During this time, the medial and lateral ends of the epiphysis may appear shaggy and irregular [ Fig. 7.9B ]. This is a normal appearance that should not be mistaken for pathology.

In older children, focal areas of irregular ossification can be seen along the posterior femoral condyles and may mimic osteochondritis dissecans (OCD) [ Fig. 7.15 ]. This normal variant is seen in up to 30% of children, most commonly between 8 and 10 years of age. It is most frequent along the posterior aspect of the lateral femoral condyle. OCD typically affects somewhat older children, and it is most common along the lateral aspect of the medial femoral condyle. With a normal variant, MRI will show a focal area of residual normal-appearing, unossified cartilage overlying the focal area of irregular ossification [ Fig. 7.15 ]. The characteristic MRI findings of OCD, including undercutting fluid, cystic change, overlying cartilage abnormality, and surrounding marrow edema, will not be present.

Irregular ossification patterns are also often seen at the proximal humeral epiphysis, proximal femoral epiphysis, and navicular bone. The ossification centers at the elbow may also be irregular as they come in, most notably the trochlea [ Fig. 7.16 ].

Sesamoid Bones

Sesamoid bones lie within tendinous insertion sites. The largest sesamoid bone in the body is the patella, which lies within the tendon of the quadriceps muscle. Two other sesamoid bones of the knee are the more common fabella within the lateral head of the gastrocnemius muscle [ Fig. 7.17 ] and the less common cyamella within the tendon of the popliteus muscle.

Sesamoid bones are very common in the hands and feet. At the first ray of the foot, sesamoids are seen within the medial and lateral slips of the hallux brevis tendon at the level of the first metatarsal head. The medial sesamoid is frequently bipartite, which may be challenging to distinguish from fracture in the setting of trauma. Chronic stress-related change, or sesamoiditis, is often seen in this location. MRI is helpful in the evaluation of acute trauma and also chronic inflammatory change.

Accessory Ossicles

Accessory ossicles are common and may be unilateral or bilateral. They may be asymptomatic and discovered incidentally, or may be associated with pain and/or susceptible to trauma. A bipartite patella is one example. This typically develops between 10 and 12 years of age and may persist into adulthood. The accessory ossicle is superolateral in position and appears after the ossification centers of the main body of the patella have fused [ Fig. 7.18 ]. This variant is seen in 1% to 6% of the population. It is much more common in males (90%) and is bilateral in 40% of cases. Stress injury or acute fracture may occur at the synchondrosis between the accessory ossicle and the parent bone, producing symptoms.

The accessory navicular ossicle is also common. This is seen in more than 20% of individuals, and is frequently bilateral. The ossicle is seen along the medial aspect of the parent navicular bone where the tibialis posterior tendon inserts. Three types are described [ Fig. 7.19 ]. A type I variant is a rounded ossicle measuring 2 to 6 mm. It is a true sesamoid bone, lying within the tibialis posterior tendon. It is usually asymptomatic, and typically does not fuse with the parent bone. The type II variant is larger, measuring 9 to 12 mm. It is connected to the parent navicular by a fibrous or cartilaginous synchondrosis. It is often symptomatic, and usually ultimately fuses with the parent navicular. A type III variant is also referred to as a cornuate navicular. There is no separate ossicle; rather, there is medial and plantar elongation of the navicular bone. This variant may be symptomatic.

An os trigonum is seen at the posterior aspect of the talus in approximately 15% of individuals [ Fig. 7.20 ]. This ossicle may predispose to posterior ankle impingement, the so-called os trigonum syndrome. This is particularly common in athletes who participate in activities that require repetitive forced plantar flexion, such as ballet dancers who dance en pointe.

Upper Extremity

The supracondylar process of the humerus is a pedunculated bony excrescence emanating from the medial aspect of anterior humeral shaft 5 to 7 cm proximal to the medial epicondyle [ Fig. 7.21 ]. This structure “points” to the joint. It is seen in 1% of individuals. It is most often asymptomatic but may be associated with a median nerve neuralgia.

An os styloideum , or carpal boss , is an accessory ossicle at the dorsal aspect of the wrist between the trapezium, capitate, and base of the second and third metacarpals [ Fig. 7.22 ]. It is seen in 1% to 3% of individuals and presents as a palpable mass.

Lower Extremity

Irregularity of the posteromedial aspect of the distal femoral metaphysis is very common [ Fig. 7.23 ]. It is sometimes referred to as a cortical desmoid. This is a “tug” lesion related to the origin of the medial head of the gastrocnemius muscle or adductor muscle insertion. It is important to be familiar with this entity, as it can sometimes appear quite irregular and may be mistaken for pathology.

A dorsal defect of the patella is a focal anomaly of ossification at the superolateral aspect of the dorsal patella. It is seen as a well-circumscribed lucency on radiographs [ Fig. 7.24A ]. On MRI, the cartilage overlying this defect is intact [ Fig. 7.24B ]. This lesion is typically asymptomatic. It must be differentiated from an OCD of the patella.

Accessory ossification centers may be seen inferior to the medial malleolus ( os subtibialis ) or lateral malleolus ( os subfibularis ) [ Fig. 7.25 ]. These accessory ossicles typically have a smooth contour and corticated margins. The differential diagnostic consideration is an avulsion injury.

A calcaneal pseudocyst presents as a triangular-shaped area of radiolucency in the anterior calcaneus [ Fig. 7.26A ]. This appearance is due to a relative deficiency of spongy bone in this location, rather than the presence of a true bony lesion. A simple bone cyst or an intraosseous lipoma may have a similar appearance [ Fig. 7.26B and C ]. When the diagnosis is not clear, CT or MRI may be helpful to distinguish these entities.

Pelvis

An accessory ossification center may develop in the cartilage of the acetabular rim, referred to as an os acetabuli. This typically appears in the second decade of life and subsequently fuses with the parent bone. This entity must be distinguished from an acetabular rim fracture.

The ischiopubic synchondrosis forms from two metaphyseal equivalents at the ischial and pubic bones. Irregularity and asymmetry of the synchondrosis is very commonly seen before fusion [ Fig. 7.27 ]. This is most often an incidental, asymptomatic finding. Fusion/ossification is highly variable, but usually occurs by the teenage years.

Constitutional Disorders of Bone

Skeletal Dysplasias

Skeletal dysplasias are defined as congenital disturbances of bone growth, structure, and modeling. Shortening of the limbs or the spine below the third percentile for a normal newborn constitutes congenital dwarfism.

Short stature may be symmetric or asymmetric. Symmetric short stature includes short-limb dwarfism, short-trunk dwarfism, and proportionate short stature.

Short-limb dwarfism is classified according to the appendicular skeletal segment involved. Rhizomelia involves the proximal appendicular skeleton, with shortening of the humeri and femurs. Mesomelia involved the middle appendicular segments, with shortening of the bones of the forearms and lower legs. With acromelia, there is shortening of the distal portions of the appendicular skeleton, including the metacarpals, metatarsals, and phalanges of the hands and feet.

Short-trunk dwarfism may be seen in the neonatal period as fatal achondrogenesis. In surviving infants it manifests as the metaphyseal chondrodysplasias, and in developing children as the mucopolysaccharidoses, the mucolipidoses, or spondyloepiphyseal dysplasia.

Proportionate short stature may be normal, may result from a variety of systemic conditions, or may be seen in the setting of entities such as cleidocranial dysostosis.

Asymmetric short stature is seen in entities such as osteogenesis imperfecta (OI) and multiple hereditary exostoses.

Symmetric Short Stature

Short-Limb Dwarfism

Rhizomelic Shortening.

Thanatophoric dysplasia, achondroplasia, and hypochondroplasia are forms of rhizomelic dwarfism. These entities develop because of variable mutations in the fibroblast growth factor receptor type 3 ( FGFR3 ) gene, which encodes a protein responsible for the velocity of endochondral growth.

Thanatophoric (“death-bearing”) dwarfism is the most common lethal skeletal dysplasia. This condition is nearly uniformly fatal, although there are rare cases of survival. Classic features include a “cloverleaf skull” caused by in utero craniosynostosis, curved long bones, dysmorphic femurs with a “French telephone receiver” appearance, and severe platyspondyly [ Fig. 7.28 ].

Achondroplasia is the most common skeletal dysplasia overall. This form of dwarfism is characterized by autosomal dominant inheritance, although the majority of cases are sporadic. Affected individuals have a normal or near-normal life span and normal mentation. An enlarged skull is seen, with frontal bossing and midface hypoplasia. The skull base is small, with a tight foramen magnum predisposing to cervicomedullary compression and related symptoms. The thorax is small, and the ribs are shortened and splayed anteriorly. The pedicles of the spine are short, and there is narrowing of the interpediculate distances progressing inferiorly along the spine. These features are associated with an increased risk for spinal stenosis. There is posterior vertebral body scalloping, kyphoscoliosis with gibbus deformity, and a profound lumbar lordosis. The iliac bones have a square shape and the acetabular roofs are flattened, leading to a “tombstone” configuration. The sacroiliac notches are narrow, giving the pelvic inlet a “champagne glass” appearance. The humeri and femurs are short, and the fibulas appear overgrown. Metaphyseal cupping is seen, with a V-shaped physeal margin (“chevron deformity”) [ Fig. 7.29 ].

Hypochondroplasia is a relatively milder form of rhizomelic dwarfism. This entity typically manifests in late childhood with clinical and radiographic findings that are similar to but less severe than those seen in achondroplasia.

Mesomelic/Acromelic Shortening.

The mesomelic dysplasias are rare. Acromelic dysplasias are relatively more common and include asphyxiating thoracic dystrophy (Jeune syndrome) and chondroectodermal dysplasia (Ellis–van Creveld syndrome). Asphyxiating thoracic dystrophy is a genetically heterogeneous disorder with a variable prognosis. Patients may present in infancy with respiratory distress caused by significantly shortened ribs with a small chest. Recurrent pulmonary infections, hypertension, and renal failure caused by progressive nephropathy may develop later in life. Characteristic radiographic findings include short, horizontal ribs with bulbous anterior ends and a long, tubular thorax. The iliac wings are small, short, and flared, and “trident acetabula” are seen [ Fig. 7.30 ]. The tubular bones of the hands and feet are shortened, and polydactyly is seen in up to one third of affected individuals.

Similar findings are seen in chondroectodermal dysplasia, an autosomal recessive, nonlethal disorder that is relatively common in the Amish community. Additional clinical manifestations include hypoplastic, brittle nails; thin, sparse hair; and dental abnormalities. Congenital heart disease is seen in two thirds of patients, with an atrial or ventricular septal defect being most common. Polydactyly is almost always present [ Fig. 7.31 ].

Short-Trunk Dwarfism

Achondrogenesis/Hypochondrogenesis.

Several forms of short-trunk dwarfism exist with varied levels of severity. The most severe form is achondrogenesis , which is fatal in the neonatal period. Affected infants have a large skull, a small thorax with short ribs, lack of mineralization of the spine and ischial and pubic bones of the pelvis, and significant micromelia (shortening of the proximal and distal segments of the appendicular skeleton). Hypochondrogenesis is a less severe variant, with infants typically surviving a few months.

Metaphyseal Chondrodysplasias.

In surviving infants with short-trunk dwarfism, four types of metaphyseal chondrodysplasias are seen which vary in severity. Affected infants have a large head, severe micromelia, and bowed limbs. With the autosomal dominant Jansen and Schmid types, irregular metaphyses and widened physes are seen. With the autosomal recessive McKusick type and Shwachman-Diamond dysplasia, epiphyseal flattening and metaphyseal irregularity are noted.

Rarer forms of short-trunk dwarfism which manifest early in life include Kniest dysplasia and spondylometaphyseal dysplasia, both with autosomal dominant inheritance. Radiographic findings include platyspondyly, anterior vertebral body wedging, and abnormal kyphosis, lordosis, or scoliosis. The metaphyses are irregular, and ossification of the epiphyses is often delayed.

Dysostosis Multiplex.

Dysostosis multiplex refers to a group of storage diseases associated with skeletal dysplasia. This group includes the mucopolysaccharidoses Hurler syndrome, Hunter syndrome, and Morquio syndrome . The mucopolysaccharidoses typically present in late infancy or early childhood. Definitive diagnosis is made by a geneticist with documentation of a specific enzymatic deficiency; however, the radiologist may first suggest the presence of a mucopolysaccharidosis. Radiographic findings are similar for Hurler and Hunter syndromes. A J-shaped sella turcica is often noted. The ribs are oar or paddle shaped, thin posteriorly and thickened anteriorly. There is characteristic inferior beaking at the anterior aspect of the vertebral bodies with a gibbus deformity, or focal kyphosis at the level of the thoracolumbar junction [ Fig. 7.32 ]. The acetabular roofs are often steep and irregular. At the hands, the proximal metacarpals are tapered. Some imaging features of Morquio syndrome overlap with those seen in Hurler and Hunter syndromes. A notable distinction is beaking of the central (rather than inferior) portion of the anterior vertebral bodies [ Fig. 7.33 ].

Proportionate Short Stature.

Proportionate short stature may be normal, as approximately 2% of all children measure below the third percentile on growth charts. It may also be seen in the setting of various systemic conditions including renal and nutritional disorders. Proportionate short stature is also often seen in children with chromosomal abnormalities.

Cleidocranial dysostosis is a relatively common autosomal dominant disorder characterized by cranial, clavicular, rib, and pelvic abnormalities. There is delayed closure of the fontanelles, and the cranial sutures are wide with wormian bones often present. The cranium is enlarged and brachycephalic. There is hypoplasia or absence of the clavicles. Eleven pairs of ribs are often seen, which may be shortened and downsloping. Delayed ossification of the symphysis pubis is common, with apparent widening on radiographs [ Fig. 7.34 ]. Affected patients develop normally and have a normal life span.

Asymmetric Short Stature

A relatively common entity associated with asymmetric short stature is osteogenesis imperfecta (OI). OI is an inherited disorder characterized by abnormal formation of type I collagen. Boys and girls are equally affected. Many different mutations have been identified, and there is a wide spectrum of clinical presentations. Historically, this condition has been divided into an autosomal recessive congenital form, which is often fatal (10%), and an autosomal dominant “tarda” form, which is clinically less severe (90%). Many types are now described. All forms of disease are characterized by osteopenia and a propensity for fractures. In the congenital form, thickened, tubular bones are seen as a result of multiple healing fractures. In the tarda from, the bones have a thin, gracile appearance. Other clinical manifestations of disease include blue sclera, poor dentition, and deafness related to otosclerosis. Radiographic findings may include diffuse osteopenia, multiple fractures of different ages, long bone bowing deformities, and wormian bones in the skull [ Fig. 7.35 ].

Tarda forms of disease are often treated with bisphosphonate therapy to increase bone calcium deposition. Intramedullary rods are used to correct bowing deformities and help prevent new fractures.

Chromosomal Disorders

Skeletal abnormalities are often seen in association with chromosomal disorders. Trisomy 21/Down syndrome is the most common chromosomal syndrome overall. Skeletal manifestations include short stature, atlantoaxial instability, 11 pairs of ribs, hypersegmentation of the sternum, flared iliac wings, and hip dysplasia, which may be seen in up to 40% of affected individuals [ Fig. 7.36 ]. Turner syndrome is seen in the setting of a 45, XO chromosomal pattern. Short stature, short fourth metacarpals, Madelung deformity, and osteopenia are characteristic.

Focal Congenital Anomalies of Bone

Proximal focal femoral deficiency is a congenital disorder consisting of a spectrum of abnormalities that may range from mild shortening and hypoplasia of the proximal femur to complete absence of the acetabulum, femoral head, and proximal femur [ Fig. 7.37 ]. It is bilateral in 15% of cases. This abnormality is thought to result from abnormal development and proliferation of chondrocytes in the proximal femoral physis in prenatal life. The acetabulum is secondarily affected. Ipsilateral fibular hemimelia (see the following paragraph) is present in more than 50% of cases. Ipsilateral foot deformities such as equinovalgus deformity are also often associated. Goals for management include maximizing the length of the affected extremity, optimizing alignment, and promoting joint stability.

Hemimelia is defined as the congenital absence of all or part of a limb. Fibular hemimelia is most common overall. Fibular abnormality may range from mild deficiency of the proximal fibula to complete absence of the bone [ Fig. 7.38 ]. Associated abnormalities of the ipsilateral lower extremity are common and may include a short, bowed tibia, femoral shortening or hypoplasia, tarsal coalition, clubfoot deformity, and absent lateral rays of the foot.

Radial dysplasia consists of a spectrum of abnormalities involving the upper extremity. Complete absence of the radius is most common, although hypoplasia may also be seen. The forearm is typically short and bowed, and there is radial deviation of the hand. The first metacarpal and/or thumb is often hypoplastic or absent [ Fig. 7.39 ]. Bilateral abnormality is seen in up to 50% of cases. Radial dysplasia is seen in association with a number of syndromes, including Holt-Oram syndrome (associated with congenital heart disease), VACTERL association ( v ertebral anomalies, a nal atresia, c ardiac anomalies, t racheo e sophageal fistula, r enal anomalies, and l imb anomalies), Fanconi anemia, and thrombocytopenia-absent radius syndrome. Management includes serial casting or splinting to improve radial deviation of the hand, surgical centralization of the hand over the ulna, and reconstruction of the thumb with pollicization of the index finger.

Amniotic band syndrome results when constricting amniotic bands form in utero and disrupt the amnion from the chorion. As the amnion separates, adhesions form which can entrap and constrict parts of the developing fetus. This may result in amputations, soft tissue syndactyly, and less commonly bony syndactyly [ Fig. 7.40 ]. Surgical treatment is primarily cosmetic.

Tarsal coalition is an abnormal connection between two or more tarsal bones due to a congenital failure of segmentation. The connection may be osseous, cartilaginous, or fibrous in nature. Talocalcaneal and calcaneonavicular coalitions are most common. Coalition affects approximately 1% of the population and is bilateral in more than 50% of affected individuals. Patients most often present in the second decade of life with pain. There may also be flatfoot deformity, limited range of motion, and a propensity for ankle and foot injury.

An osseous coalition may be evident on radiographs. A calcaneonavicular coalition is typically well demonstrated on an oblique radiograph of the foot. An “anteater sign” may be seen on the lateral view, with abnormal elongation of the anterior process of the calcaneus [ Fig. 7.41 ]. A talocalcaneal coalition is often more subtle on radiographs, although sometimes a “C sign” can be seen on a lateral view [ Fig. 7.42 ]. Secondary radiographic signs of tarsal coalition include pes planus deformity and a talar beak, or dorsal extension of the talar head. A cartilaginous or fibrous coalition is suggested on radiographs by a narrowed joint space between the involved bones, with irregularity of the articular margins.

Cross-sectional imaging is helpful to determine the nature and extent of a tarsal coalition. Osseous coalition is well demonstrated on CT scan [ Figs. 7.41 and 7.42 ]. Osseous cartilaginous, and fibrous coalitions are all well seen on MRI, and associated findings such as marrow edema may be noted.

Conservative management includes immobilization with casting or orthotics, nonsteroidal antiinflammatory drugs, and physical therapy. Surgical resection is performed for symptomatic coalition refractory to conservative management. The coalition is excised, with interposition of fat graft or extensor digitorum brevis tendon to halt regrowth. Subtalar arthrodesis or triple arthrodesis (subtalar, calcaneocuboid, and talonavicular) may be performed for advanced cases with a suboptimal response to management with resection.

Sclerosing Bone Dysplasias/Disorders of Increased Bone Density

Osteopetrosis may be caused by several different genetic mutations, all ultimately leading to osteoclast dysfunction. There is a failure of resorption of cartilage and bone matrix, with resultant dense, brittle bones with marrow underdevelopment and a propensity for fractures. For clinical purposes, the different forms of osteopetrosis are distinguished by age at onset. Early-onset, infantile disease is characterized by autosomal recessive inheritance and is most severe. Patients present in infancy with hepatosplenomegaly, pancytopenia, multiple infections, and leukemia. Prognosis is poor, and early death is common. Later-onset (“tarda”) forms of disease are characterized by autosomal dominant inheritance and may present in childhood or adolescence. Affected individuals sustain multiple fractures but have a normal life span.

Characteristic radiographic findings of osteopetrosis include diffusely increased bone density, “Erlenmeyer flask” deformity of the metaphyses caused by undertubulation, and a characteristic “bone-within-bone” or “picture frame” appearance [ Fig. 7.43 ]. The skull base is thickened, with obliteration of the mastoid air cells and paranasal sinuses and encroachment on the cranial nerves. Although total body calcium levels are typically high, serum calcium levels are often paradoxically low because nearly all calcium present is bound in highly mineralized, dense bone. Thus superimposed rachitic changes can be seen. Bone marrow transplantation may be curative, replenishing the marrow with normally functioning osteoclasts.

Pyknodysostosis is an autosomal recessive disorder that usually presents in infancy. It is a form of short-limbed, acromelic dwarfism. Patients have short stature, short, broad hands and feet, and micrognathia. Fractures are frequent. On radiographs, there is diffuse osteosclerosis. The cranium is enlarged due to significantly delayed closure of the fontanelles and sutures, and wormian bones may be seen. In the extremities, there is resorption of the phalangeal tufts with an appearance similar to acro-osteolysis. Bony resorption may also be seen at the distal clavicles.

Osteopoikilosis is an autosomal dominant condition characterized by multiple small foci of sclerosis predominantly involving the cancellous bone of the carpal and tarsal bones, pelvis, and scapulae in a periarticular distribution [ Fig. 7.44 ]. It is asymptomatic, often picked up incidentally, and does not progress. Lesions may show increased uptake on bone scan.

Osteopathia striata is an asymptomatic entity characterized by bilateral, symmetric, lucent, linear striations in the metadiaphysis of long bones. This may be an isolated finding in the sporadic form of this condition. Alternatively, there may be associated cranial sclerosis in the X-linked dominant form of this entity.

Melorheostosis is an uncommon condition that may be sporadic or may be associated with autosomal dominant inheritance. Disease is usually limited to a single extremity, with the lower extremities more frequently affected than the upper extremities. Children present with limb asymmetry which may be painless or associated with bone pain and joint stiffening. On radiographs, there is dense, linear cortical hyperostosis along the long axis of the bone, often likened to the appearance of dripping candle wax. This entity is associated with increased uptake on bone scan.

Caffey disease (infantile cortical hyperostosis) is an idiopathic condition that occurs in the first few months of life. The average age at onset is 9 weeks, and it is seldom seen beyond the age of 6 months. Boys and girls are equally affected. Clinically, infants present with irritability, low-grade fever, and soft tissue swelling surrounding involved areas. The erythrocyte sedimentation rate may be elevated. On radiographs, there is symmetric periosteal new bone formation with overlying soft tissue edema. The mandible, clavicles, ribs, humeri, ulnae, femurs, scapulae, and radii are most often involved [ Fig. 7.45 ]. Disease is usually self-limited, resolving over several months.

Systemic Skeletal Disorders

Metabolic Disorders

Rickets

Rickets develops because of a relative or absolute deficiency in vitamin D or its derivatives, resulting in failure of mineralization of the normal growing cartilage into bone. There are several causes of rickets. It may be related to nutritional deficiencies, malabsorption of vitamin D, or renal osteodystrophy. It is almost always diagnosed in children younger than 2 years. The clinical manifestations of rickets include failure to thrive, weakness, short stature, bowing deformities, and a predisposition to fractures.

In one third of patients, the radiographic manifestations of rickets may be seen before it is clinically evident. Classic radiographic findings are seen after 4 to 6 weeks of vitamin D deficiency. The rapidly growing physes of the knees and wrists are typically abnormal, with disruption of regulated chondrocyte apoptosis at the ZPC resulting in abnormal endochondral ossification. Mineralization does not occur, and the hypertrophic zone widens. Radiographically, there is physeal widening and cupping, fraying, and irregularity of the metaphysis [ Fig. 7.46 ]. Generalized osteopenia is seen. Craniotabes, or a “ping-pong ball” deformity of the skull, may be noted. The classic “rachitic rosary” at the anterior rib ends is not commonly seen today. With treatment, there is mineralization of the ZPC and physeal thickness normalizes. This results in a dense metaphyseal band.

Hyperparathyroidism

Primary hyperparathyroidism is caused by increased parathyroid hormone (PTH) secretion in the setting of a parathyroid adenoma or diffuse parathyroid hyperplasia. These entities are relatively rare in children and are most often associated with the multiple endocrine neoplasia (MEN) syndromes. In secondary hyperparathyroidism, PTH secretion is increased due to chronic hypocalcemia. This is most often caused by chronic renal failure in children, but may also be related to other disorders of calcium metabolism. PTH stimulates the osteoclasts and leads to resorption of bone at multiple sites. The most specific radiographic manifestation of hyperparathyroidism is bony resorption along the radial aspect of the middle phalanges of the second, third, and fourth digits. With more advanced disease, resorption may be seen along the distal clavicles and medial aspects of the humeral and femoral necks and proximal tibial metaphyses [ Fig. 7.47 ]. Characteristic brown tumors (osteoclastomas) may be seen, reflecting localized, intraosseous accumulation of fibrous tissue. Generalized osteopenia is characteristic.

Renal Osteodystrophy

Renal osteodystrophy comprises the variety of changes that occur in the skeleton in patients with chronic renal insufficiency. With decreased glomerular filtration, there is retention of phosphate and a slight decrease in calcium levels. This stimulates PTH and results in the mobilization of calcium and phosphate from bone. When there is severe growth failure in the setting of renal osteodystrophy, the radiographic changes of hyperparathyroidism predominate. With skeletal growth, the changes of rickets may be seen. Osteosclerosis is often demonstrated. This may be generalized or may be most pronounced along the vertebral body endplates with the characteristic “rugger jersey spine” appearance [ Fig. 7.48 ].

Hypothyroidism

Hypothyroidism is the most common metabolic abnormality diagnosed with routine newborn screening. It most often results from congenital absence or hypoplasia of the thyroid gland. It occurs three times more frequently in girls than in boys. Thyroid hormone is essential for bone growth and maturation, and also for development of the central nervous system. With deficiency of thyroid hormone, skeletal maturation is delayed out of proportion to linear growth. The bone age is typically greater than two standard deviations below the mean. Epiphyseal dysgenesis is characteristic. Ossification of the epiphyses is delayed, and the pattern of ossification is often irregular. Multiple, fragmented ossification centers may be seen, which eventually coalesce. Epiphyseal margins are typically irregular. There is delay in closure of the cranial sutures, and wormian bones are common. The sella may be enlarged due to pituitary hyperplasia, and brachycephaly may result from decreased growth at the spheno-occipital synchondrosis.

Hypervitaminosis A

Hypervitaminosis A has become rare in the pediatric population. Historically, it has been attributed to the use of fish liver oil and other similar preparations used in the treatment and prevention of xerophthalmia. More recently, it has been linked to high-potency vitamin A analogs used to treat dermatologic disorders. Vitamin A toxicity typically develops at least 6 months after excess intake begins. Clinically, patients present with anorexia, irritability, dry, pruritic skin with desquamation, lip fissuring, focal areas of swelling and pain along the extremities, and hepatomegaly.

Radiographically, exuberant periosteal new bone formation is seen along the ulnae, metatarsals, and phalanges. Undulating cortical thickening may be noted. The main differential diagnostic consideration is infantile cortical hyperostosis, or Caffey disease. These two entities may be distinguished based on patient age and distribution of disease. Caffey disease is most often seen in the first few months of life, whereas hypervitaminosis A most commonly presents between 1 and 3 years of age. With Caffey disease, hyperostosis along the mandible and clavicles is classically seen. A unique radiographic feature of vitamin A toxicity is premature central growth plate closure, resulting in a cone-shaped epiphysis with invagination into the metaphysis. Clinical symptoms and radiographic abnormalities resolve with cessation of vitamin A intake.

Scurvy

Scurvy is a metabolic bone disease that is rarely seen today. It is caused by a dietary deficiency of vitamin C. Historically, it was seen in babies fed pasteurized or boiled milk. Today, it is occasionally seen in children with highly selective diets. It almost always presents after 6 months of age. Lack of vitamin C results in poor bone matrix/collagen formation, with several characteristic radiographic findings. Resorption of calcified cartilage is diminished on the metaphyseal end of the physis. This results in a thick, opaque ZPC, referred to as the white line of scurvy or white line of Frankel. Subjacent to this, a lucent band designated the scurvy zone is seen. Corresponding findings are seen in the epiphysis, with a thick, peripheral shell of calcified cartilage surrounding a central region of lucency. This produces the “Wimberger ring” that is characteristic of scurvy [ Fig. 7.49A ].

Both the thickened ZPC and the lucent scurvy zone are prone to fracture. Metaphyseal fractures are common, with associated subperiosteal hemorrhage. Subperiosteal hemorrhage is initially seen as a soft tissue opacity along the shaft of a tubular bone, which eventually mineralizes and becomes the new cortex [ Fig. 7.49B ]. A prominent metaphyseal spur (“Pelkan spur”) may be seen after a fracture, with lateral extension of the dense, thickened ZPC.

Lead Poisoning

Lead poisoning is the most common type of heavy metal poisoning seen in children. It is usually related to the ingestion of lead-based paint chips found in older homes. Clinically, patients may present with abdominal pain, encephalopathy, peripheral neuropathy, and anemia. On abdominal radiographs, lead-based paint chips may be visualized in the bowel [ Fig. 7.50 ]. Bony manifestations are typically a late finding of chronic lead exposure. Lead toxicity interferes with the resorption of calcified cartilage in the primary spongiosa. This accumulates and leads to the formation of the dense, radiopaque metaphyseal bands (“lead lines”) that are characteristic of this disease [ Figs. 7.9 and 7.50 ]. The major differential diagnostic consideration is the normal, physiologic dense bands that are typically seen in the metaphyses of the more rapidly growing long bones in young children. Lead lines will be seen in all metaphyses, including those of the more slowly growing bones such as the fibula.