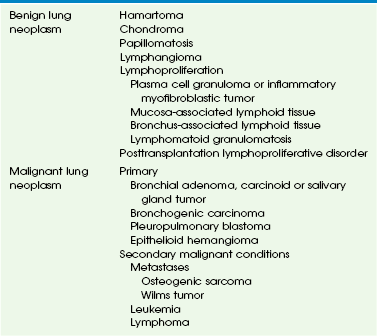

Chapter 55 Pulmonary neoplasm is much less common in children than in adults. Affected children may present clinically with respiratory symptoms or pulmonary neoplasm may be detected incidentally on a chest radiograph in an asymptomatic child. In a recent series of 204 pediatric lung tumors, the ratio of primary benign to primary malignant to secondary malignant pulmonary neoplasms (i.e., metastases) is 1.4 : 1 : 11.6.1 Primary lung tumors represent only 0.19% of all pediatric neoplasms. Metastatic lung tumors are approximately 12 times more common than primary lung tumors in children. A list of benign and malignant lung neoplasms is summarized in Table 55-1. Primary benign pulmonary neoplasms in children are far less common malignant pulmonary neoplasms, including both primary and secondary lesions. The imaging characteristics of benign lung neoplasms are summarized in Table 55-2. Table 55-2 Imaging Characteristics of Benign Lung Neoplasm (Nonlymphoproliferative) Etiology: Pulmonary hamartoma, originally thought to represent a congenital lesion, is now considered a true benign mesenchymal neoplasm. It contains predominantly cartilage, fat, and fibrous tissue. Occasionally, pulmonary hamartoma may also have smooth muscle, bone, and entrapped respiratory epithelium, which grow slowly.2 Pulmonary hamartoma is rare in children (the peak incidence is in the fourth to sixth decades); however, it is the most common primary benign pulmonary neoplasm accounting for 7% to 14% of all solitary pulmonary nodules in children.3 Ninety percent of pulmonary hamartomas are parenchymal in location. They usually present as incidental findings, although a large pulmonary hamartoma could cause respiratory distress. Imaging: The typical radiographic appearance of pulmonary hamartoma is a smooth or slightly lobulated, solitary pulmonary nodule or mass, usually located in the peripheral portion of the lungs. Characteristic punctuate or popcorn-like calcifications may be seen in approximately 10%. On computed tomography (CT), it is typically a well-circumscribed pulmonary nodule that is less than 2.5 cm in diameter. Pulmonary hamartoma often contains fat or calcification, which, in a solitary pulmonary nodule, is considered diagnostic (Fig. 55-1).4 Treatment and Follow-up: Pediatric patients with pulmonary hamartoma require no further treatment unless it grows rapidly or the patient becomes symptomatic because of recurrent pneumonia or atelectasis caused by the mass effect from the tumor.5 In such situations, surgical resection is usually curative. Etiology: Pulmonary chondroma is a benign tumor composed of a well-differentiated benign cartilage with lack of bronchial epithelium.6 Pulmonary chondroma tends to occur before 30 years of age (82%), mainly in young women (85%). Affected persons are usually asymptomatic. Pulmonary chondroma is associated with the Carney triad.7 This syndrome commonly affects three organs: (1) stomach (gastrointestinal stromal tumor, 75%) (Fig. 55-2, B), (2) lung (pulmonary chondroma, 15%), and (3) paraganglionic system (paraganglioma, 10%). However, tumors arising from the adrenal gland (adrenal adenoma or pheochromocytoma, 20%) and the esophagus (leiomyoma, 10%) have also been reported in association with the Carney triad. The majority of patients present with two of three neoplasms. Seventy-five percent of patients with the Carney triad have pulmonary chondroma(s). Figure 55-2 Pulmonary chondroma. Imaging: Pulmonary chondroma may be single (40%), multiple unilateral (25%), or bilateral (15%) without predilection for specific lobe or side of lung.7 Chest radiography usually shows well-demarcated, often multiple, lung masses with central or popcorn-like calcification (Fig. 55-2, A). When calcified (45%), the appearance of chondroma is indistinguishable from that of pulmonary hamartoma on imaging studies. Etiology: Recurrent respiratory papillomatosis (RRP) is characterized by mucosal papillomas, which are ingrowths of squamous cell–lined fibrovascular core in the lumen of central airways. It is the most common neoplasm that occurs in the larynx of children. RRP is caused by the human papilloma virus (HPV) types 6 and 11, which is typically acquired during vaginal birth. The primary lesions commonly affect the larynx but may spread to the lung parenchyma (1.8%) especially if surgical or laser therapy had been provided earlier.8 The ultimate prognosis is poor when pulmonary involvement occurs. Malignant transformation into squamous cell carcinoma may occur.9 Imaging: On chest radiography, RRP typically presents as bilateral, multiple nodular and cystic lesions of varying size containing air or debris. Postobstructive atelectasis, bronchiectasis, or secondary infection presenting as consolidation may be also seen.10 On CT, usually, scattered nodules are seen in the lungs (Fig. 55-3), and these nodules may enlarge, become air-filled cysts, or form large cavities with thin or thick walls.11 CT virtual bronchoscopy may be useful to evaluate mural nodules within the central airways. Figure 55-3 Recurrent respiratory papillomatosis. Etiology: Lymphatic malformation, previously referred to as lymphangioma, is characterized by a benign proliferation of nonfunctional lymphatic tissue that may involve nearly every organ of the body. Only 1% of lymphatic malformations remain confined to the chest. Primary pulmonary lymphatic malformation is even less common.14 Affected persons are often asymptomatic. However, some may present with compressive symptoms such as cough, dyspnea, stridor, or even pneumothorax. Younger patients tend to have lesions that affect the lung.15 Imaging: On chest radiography, lymphatic malformation typically presents as a masslike opacity. The most common CT finding is a smooth, well-marginated, nonenhancing, cystic mass. In neonates and infants, this may simulate congenital pulmonary airway malformation (CPAM) or diaphragmatic hernia. Older children may have a solid, low-attenuation, masslike lesion that may mimic pneumonia or tumors (e-Fig. 55-4). e-Figure 55-4 Lymphatic malformation. In recent years, the incidence of lymphoproliferative disorders has increased because of increase in pediatric organ transplantation, prevalence of human immunodeficiency virus (HIV) infection, and development of more potent immunosuppressive therapies. The most common lymphoproliferative disorders affecting lungs in children are plasma cell granuloma, mucosa-associated and bronchus-associated lymphoid tissue, lymphocytic interstitial pneumonitis, lymphomatoid granulomatosis, and posttransplantation lymphoproliferative disorder. The imaging characteristics of lymphoproliferative disorders involving lungs are listed in Table 55-3. Table 55-3 Lymphoproliferative Disorders of the Lungs Etiology: Plasma cell granuloma is the most common tumorlike abnormality in the lungs of children. It arises in the lung parenchyma but may also involve the mediastinum or pleura. Due to the complexity and variable histologic characteristics, it is known by several different terms, including inflammatory or postinflammatory pseudotumor, fibroxanthoma, myofibroblastic tumor, fibrous histiocytoma, xanthogranuloma, or histiocytoma.17,18 Recently, it has been termed inflammatory myofibroblastic tumor (IMT) because myofibroblasts, fibroblasts, and histiocytes are the main constituents of this tumor (Fig. 55-5, B).19 A substantial proportion of tumors have ALK1 gene mutations.20 The World Health Organization (WHO) currently recognizes IMT as a low-grade mesenchymal malignancy. The majority of children with IMT are older than 5 years, although it has been reported in younger children and even infants. Approximately 60% of affected children are symptomatic, typically presenting with fever, cough, chest pain, dyspnea, wheezing, or hemoptysis. Figure 55-5 Inflammatory myofibroblastic tumor. Imaging: Radiographically, IMTs may be seen as solitary (95%) or multiple (5%). IMTs are usually sharply circumscribed, lobulated mass(es) of varying sizes, typically located in the peripheral portion of the lungs. IMT may occasionally be endobronchial. On CT, it usually presents as a soft tissue mass with either homogeneous or heterogeneous attenuation (see Fig. 55-5, A). Although IMT does not enhance substantially, a thick enhancing rim has been reported. Less commonly, it may present with both solid and cystic components. IMT may also have an infiltrative pattern simulating an aggressive malignancy.21 If the mediastinum is involved or the mass contains calcifications (15% to 25%), IMT may mimic a germ cell tumor, neuroblastoma, or metastatic osteosarcoma in pediatric patients. Etiology: Mucosa-associated lymphoid tissue (MALT, or pseudolymphoma) is rare in children. Affected persons generally are not severely ill but may have nonspecific respiratory symptoms. Lymphoma has been reported to develop in some cases of MALT. It may be quite difficult to clearly differentiate pseudolymphoma from a true lymphoproliferative condition, even by using modern immunofluorescence techniques. Experts currently disagree about whether MALT should be considered a premalignant or a postinflammatory condition. Bronchus-associated lymphoid tissue (BALT) is a subcategory of the more widely distributed MALT. BALT is a lymphoid aggregate located in the submucosal area of bronchioles, which may become hyperplastic because of chronic antigen stimuli.22 It has been suggested that BALT is related to a hypersensitivity response to unidentified antigens. BALT has two forms: (1) lymphoid interstitial pneumonia and (2) follicular bronchitis or bronchiolitis. Lymphoid interstitial pneumonia type BALT is commonly seen in pediatric patients with acquired immunodeficiency syndrome (AIDS) or other immune compromise. Follicular bronchitis or bronchiolitis type of BALT typically occurs in children with chronic infection, connective tissue disorders, or immunodeficiency disorders and as a hypersensitivity reaction. Imaging: On chest radiography, MALT typically presents as discrete, often multiple lesions, usually with air bronchograms ranging from 2 to 5 cm in diameter. A pleural effusion is commonly seen. A diffuse reticulonodular opacity, often associated with hyperinflation, is the common radiographic finding of BALT (e-Fig. 55-6, A). On CT, the usual imaging appearance of BALT consists of small centrilobular nodules (foci of lymphoid proliferation) and a ground-glass opacity predominantly involving the lower lobes (see e-Fig. 55-6, B). In patients with advanced BALT, bronchiectasis and peribronchovascular consolidation caused by recurrent infection and chronic airway obstruction may present. e-Figure 55-6 Bronchus-associated lymphoid tissue. Treatment and Follow-up: Aggressive management (e.g., complete surgical excision, radiotherapy, chemotherapy, or a combination of all of these) is the current treatment of choice for MALT. Because of the wide extent of disease often associated with BALT, surgical excision may be considered only for a minority of patients. Chemotherapy is the treatment of choice for the majority of patients with BALT. Etiology: Lymphocytic interstitial pneumonitis (LIP) is characterized by diffuse proliferation of polyclonal lymphocytes and plasma cells in the pulmonary parenchymal interstitium, which expands to the alveolar septa. It is considered an AIDS-defining illness in children younger than 13 years old who are infected with HIV because LIP is rarely idiopathic. Imaging: On chest radiography, LIP typically presents with reticular or reticulonodular opacities predominantly in the bilateral lower lung zones.23 On high-resolution CT, diffuse centrilobular and subpleural nodules (representing local proliferation of lymphoid germinal centers), areas of ground-glass opacity, and bronchovascular and interstitial thickening in both lungs are often seen (Fig. 55-7). Thin-walled cysts and bronchiectasis may be also present.24 Figure 55-7 Lymphocystic interstitial pneumonitis. Treatment and Follow-up: Steroid and other immunosuppressive agents are used for treating LIP with variable results. Prognosis of children with LIP depends on the associated underlying disease. Progressive honeycomb fibrosis or infectious complications may lead to increased mortality. Low grade B-cell lymphoma may develop in rare cases.25 Etiology: Lymphomatoid granulomatosis, also known as pseudolymphoma, angiocentric lymphoma, or angiocentric immunoproliferative lesion, is characterized pathologically by an angiocentric and angiodestructive lymphocytic infiltration. It is considered an aggressive multisystem disease with a poor prognosis. The lung is often the primary site of involvement. This disease is associated with Epstein-Barr virus (EBV) infection in immunocompromised individuals. Progression of lymphomatoid granulomatosis to lymphoma occurs in 12% to 47% of patients, with the mortality rate over 50%.26 Imaging: On chest radiography, bilateral, poorly defined, nodular and confluent lesions with a basilar predominance are usually seen (e-Fig. 55-8). Characteristic CT findings of lymphomatoid granulomatosis include peribronchovascular distribution of nodules (which reflects the tendency of lymphomononuclear cells to infiltrate the subintimal region of medium-sized arteries and veins), small thin-walled cysts, and conglomerate small nodules.24,27 Lesions may cavitate, mimicking Wegener granulomatosis. e-Figure 55-8 Lymphomatoid granulomatosis type III (form of B cell lymphoma). Etiology: Posttransplantation lymphoproliferative disorder (PTLD) is a consequence of chronic immunosuppression following solid organ transplantation or, less often, bone marrow transplantation.29–32 It is believed to be induced by exposure to EBV. The lesions consist of uncontrolled proliferation of B lymphocytes ranging from benign lymphoid hyperplasia to invasive malignant lymphoma. The incidence of PTLD (1% to 18%) varies with the type of organ transplanted. It occurs most frequently in lung or heart-lung transplantation patients, likely because of the higher levels of immunosuppression required for these organ transplantations.29,33–35 It is also more common in pediatric patients than in adult transplantation patients, possibly because of the lack of prior exposure to EBV. Improved surveillance, earlier diagnosis, and close monitoring of immunosuppression have led to a decreased incidence of PTLD in recent years, as well as a more favorable outcome. The most common sites for PTLD are the tonsils, cervical nodes, gastrointestinal tract, and the chest.36,37 Intrathoracic PTLD tends to present earlier compared with extrathoracic PTLD. PTLD tends to occur within the allograft organ itself, as well as in adjacent anatomic regions.38 Heart transplantation is the sole exception to this predilection.39 Clinical symptoms of PTLD are often vague and include lethargy, fever, and weight loss. Biopsy is typically required to confirm the diagnosis.

Neoplasia

Neoplasia

Primary Benign Pulmonary Neoplasms

Neoplasm

Imaging Characteristics

Hamartoma

Smooth or slightly lobulated, sharply defined mass, occasionally calcified (“popcorn”)

Fat and calcification in solitary pulmonary mass on computed tomography is diagnostic

Chondroma

Solitary or multiple nodules; commonly (45%) calcified; associated with the Carney triad

Respiratory papillomatosis

Rarely (<1%) intrapulmonary;

Bilateral, multiple subpleural solid or cystic nodules; may be associated with bronchiectasis or atelectasis

Lymphatic malformation

Rarely intrapulmonary; well-marginated, nonenhancing cystic mass; may simulate congenital pulmonary airway malformation or diaphragmatic hernia in neonates; or solid, low-attenuation mediastinal or pulmonary mass in older children

Hamartoma

Chondroma

A, A 14-year-old boy in the setting of the Carney triad. Axial unenhanced computed tomography image shows a large right parahilar mass (arrowheads) with extensive calcifications. B, Upper gastrointestinal study of the same patient demonstrates a large ulcerated exophytic soft tissue mass (arrows) in the stomach consistent with gastric leiomyosarcoma.

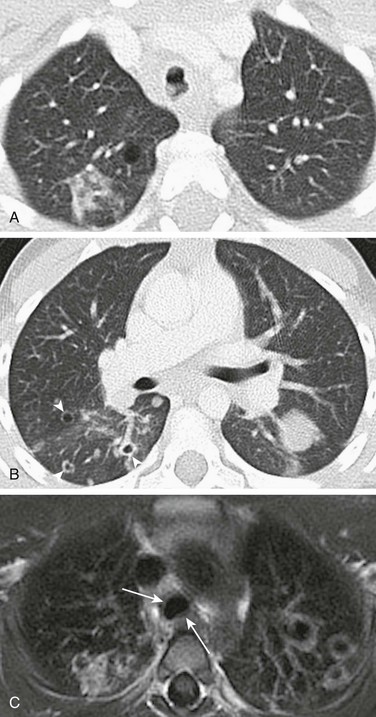

Recurrent Respiratory Papillomatosis

A, Axial lung window computed tomography image obtained in a 5-year-old girl with recurrent respiratory papillomatosis shows multiple intratracheal soft tissue nodules. B, Multiple parenchymal papillomas are also present, some of which show cavitation (arrowheads). C, An axial T1-weighted magnetic resonance image shows cavitating lesions in both lungs and mildly thickened tracheal walls (arrows).

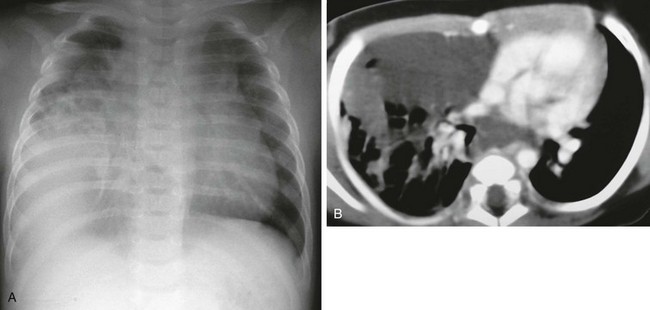

Lymphatic Malformation

Biopsy-proven lymphatic malformation in a 4-year-old boy. A, A chest radiograph demonstrates a mass in the right hemithorax. B, An axial enhanced computed tomography image shows a low-attenuation infiltrating mass in the middle mediastinum and right middle lobe.

Lymphoproliferation

Disorder

Imaging Characteristics

Plasma cell granuloma or inflammatory myofibroblastic tumor

Solitary or multiple; sharply circumscribed mass; may be locally invasive; 15% to 25% have calcification; may be composed of both solid and cystic components

Mucosa-associated lymphoid tissue proliferation (pseudolymphoma)

2- to 5-cm discrete lesions with air bronchograms; may evolve into malignant lymphoma; pleural effusion common

Bronchus-associated lymphoid tissue proliferation

Diffuse reticulonodular pattern on chest radiography

Small centrilobular nodules and ground glass opacity on computed tomography

Lymphoid interstitial pneumonia

Seen in patients with acquired or congenital immunodeficiency as reticular or reticulonodular opacities on chest radiography; diffuse centrilobular and subpleural nodules on high-resolution computed tomography; associated with ground-glass opacity; bronchovascular and interstitial thickening

Lymphomatoid granulomatosis

Seen in immunocompromised patients

Multiple nodules or confluent masses that frequently cavitate; basal predominance

Posttransplantation lymphoproliferative disorder

Solitary or multiple lung masses or consolidation noted months to years after solid organ or bone marrow transplantation; may have associated mediastinal and extrathoracic adenopathy; large lesions may cavitate

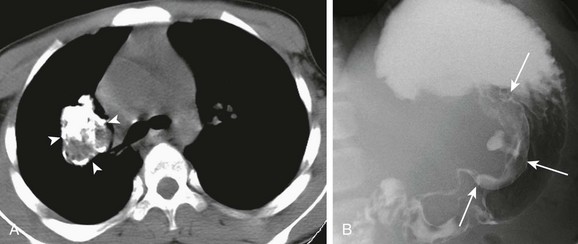

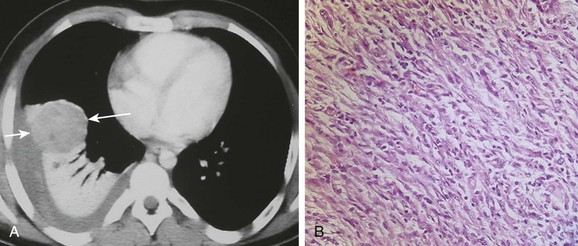

Plasma Cell Granuloma or Inflammatory Myofibroblastic Tumor

An afebrile 13-year-old boy who presented with increasing dyspnea and right-sided pleuritic chest pain. A, An axial contrast-enhanced computed tomography of the chest shows a rounded heterogeneously enhancing lesion (arrows) located adjacent to an area of atelectatic lung. Pleural fluid at the same level demonstrates increased attenuation consistent with a hemothorax. B, A photomicrograph (hematoxylin-eosin stain) of the surgical specimen reveals the presence of both spindle-shaped myofibroblasts and inflammatory cells consistent with an inflammatory myofibroblastic tumor of the lung.

Mucosa-Associated Lymphoid Tissue and Bronchus-Associated Lymphoid Tissue

A 5-year-old girl who presented with worsening shortness of breath and decreased oxygen saturation. A, A chest radiograph shows hyperinflation with increased streaky interstitial opacities in both lungs. B, An axial lung window computed tomography image demonstrates air trappings, mosaic perfusion, and diffuse opacity with cystic bronchiectasis.

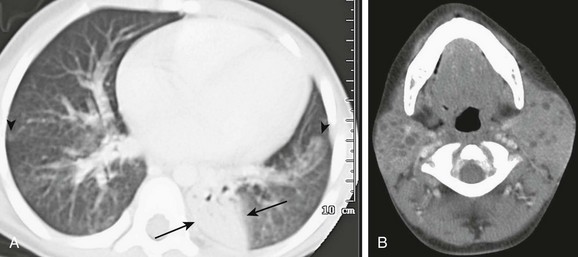

Lymphocytic Interstitial Pneumonitis

An 8-year-old girl with human immunodeficiency virus (HIV) infection with increasing shortness of breath. A, An axial computed tomography (CT) image shows bilateral patchy areas of ground-glass attenuation, right greater than left, poorly defined nodules (arrowheads) and an area of consolidation in the left lower lobe (arrows). B, An axial, enhanced CT image of neck demonstrates multiple, bilateral parotid lymphoepithelial cysts consistent with HIV parotitis.

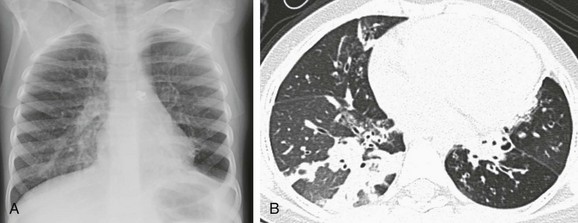

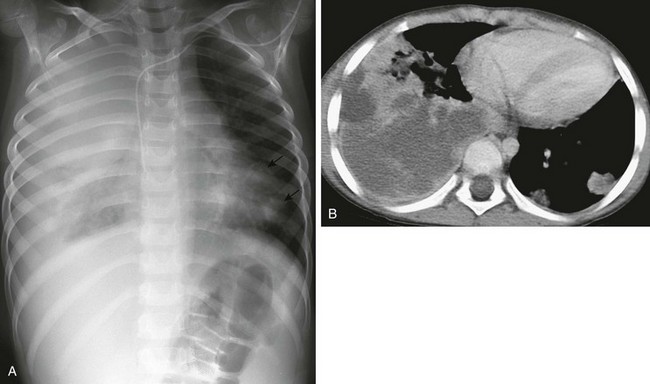

Lymphomatoid Granulomatosis

A 5-year-old boy with severe combined immunodeficiency who presented with cough and shortness of breath. A, A chest radiograph demonstrates marked opacity of the right lung and cardiomediastinal shift to the left, with multiple left-sided nodules (arrows). B, An axial enhanced computed tomography image shows multiple left-sided cavitating nodules in addition to a large heterogeneous, predominantly low-attenuation, and confluent density within the right lung.

Posttransplantation Lymphoproliferative Disorder