Pulmonary neoplasm and lymphoproliferative disorders may present with diffuse lung abnormalities. The goal of this chapter is to discuss the various patterns of diffuse pulmonary neoplasm and lymphoproliferative disease and when these entities should be considered in the differential diagnosis.

PULMONARY MALIGNANCIES: MECHANISM OF SPREAD

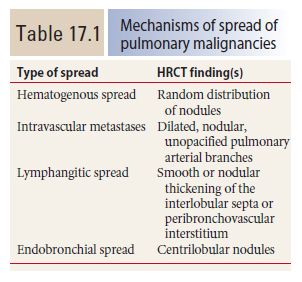

Neoplasms may result in diffuse lung abnormalities by several different mechanisms (Table 17.1). These result in different appearances on HRCT.

Hematogenous Spread

Hematogenous spread of tumor to small pulmonary arteries is the most common mechanism by which malignancy results in diffuse lung involvement. The primary HRCT manifestation of hematogenous spread is randomly distributed pulmonary nodules (see Chapter 3) (Fig. 17.1).

Nodules involve the entire lung and have a diffuse and uniform distribution with involvement of pleural surfaces. The nodules may be lower lobe predominant because there is usually greater blood flow to this location. Nodules are usually of soft tissue attenuation and may range in size from a few millimeters in size, when first recognized, to many centimeters. The nodules tend to be similar in size.

The differential diagnosis includes other causes of random nodules, including miliary tuberculosis and miliary fungal infection. Clinical history may be helpful in distinguishing infections from neoplasm. The size of nodules may be helpful when the clinical presentation is unclear. Large nodules are more likely to represent metastases than infection. Miliary infections uncommonly produce nodules larger than 5 mm.

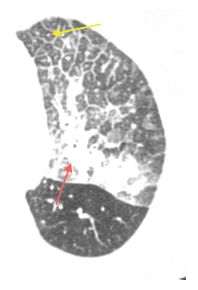

Intravascular Metastases

In occasional patients, tumor embolism to pulmonary arteries results in intravascular metastases, tumor deposits that grow within the lumen of the artery. These may be seen with various neoplasms, but are most common with very vascular primary tumors (e.g., sarcomas) and tumors that result in invasion of large veins (e.g., hepatoma and renal cell carcinoma).

Intravascular metastases result in focally dilated, nodular, beaded, or lobulated pulmonary artery branches (Fig. 17.2). Intravascular filling defects may be visible if contrast agent is injected. This appearance may mimic pulmonary embolism, but smooth luminal filling defects, resembling thrombotic pulmonary emboli, are rare as an isolated finding.

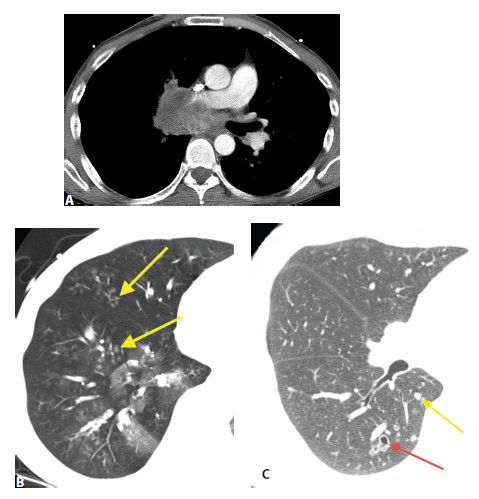

Lymphangitic Spread

Pulmonary lymphatics predominate in the parahilar peribronchovascular interstitium, centrilobular regions, interlobular septa, and subpleural interstitium. Tumors that spread via the lymphatics may demonstrate abnormalities associated with these structures, particularly the interlobular septa and peribronchovascular interstitium (Fig. 17.3). Thickening of these structures may be smooth or nodular.

The most common tumors to produce this pattern include lymphoma and cancers of the lung, breast, thyroid gland, stomach, pancreas, prostate, and head and neck. In many cases, lymphangitic spread occurs as a result of hematogenous dissemination to small vessels, with tumor invasion of the interstitium. Thus an overlap between the appearance of hematogenous spread and lymphangitic spread may be seen in some patients.

Interlobular septal thickening is the result of direct invasion of the pulmonary lymphatics and interstitium by a lung metastasis or primary tumor. Peribronchovascular interstitial thickening is most commonly seen in patients with mediastinal metastases that spread peripherally via lymphatics.

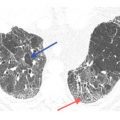

Figure 17.1

Hematogenous metastases. HRCT in a patient with metastatic medullary thyroid carcinoma shows diffuse nodules, less than 1 cm in diameter, with a random distribution. The random distribution reflects hematogenous spread of tumor to the lungs.

The differential diagnosis of nodular interlobular septal and peribronchovascular interstitial thickening includes other causes of perilymphatic disease including sarcoidosis, pneumoconioses, amyloidosis, and lymphoid interstitial pneumonia (LIP). When smooth thickening of these structures is present, the primary differential consideration is pulmonary edema.

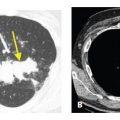

Figure 17.2

Intravascular metastases in chondrosarcoma. A. Dilated tubular, branching pulmonary arteries (arrows) are visible in the central and peripheral lung. These represent pulmonary arterial branches whose lumens are filled with tumor. Multiple nodular metastases are also visible. B. Coronal reformatted image shows the irregularly dilated arteries supplying the lower lobes (arrows). This reflects the presence of extensive intravascular tumor emboli (arrows).

Figure 17.3

Lymphangitic metastases. Focal smooth interlobular septal thickening is noted in the left upper lobe in a patient with lung cancer. Note the polygonal lobules outlined by the thickened septa. Centrilobular arteries are visible in their centers (yellow arrow). Central peribronchovascular interstitial thickening is also present (red arrow).

Endobronchial Spread

Endobronchial spread of tumor is rare with extrathoracic malignancies. It is more commonly seen with primary bronchogenic carcinomas, particularly invasive mucinous adenocarcinoma or squamous cell carcinoma. Endobronchial spread of tumor may closely resemble bronchopneumonia with airway impaction and centrilobular nodules. Consolidation or ground glass opacity may be due to atelectasis or post-obstructive pneumonitis (Fig. 17.4A, B). The most common extrathoracic primaries to show endobronchial spread include melanoma, breast, renal, pancreatic, and colon cancers. Tracheobronchial papillomatosis is associated with infection by the human papilloma virus. Papillomas involving the larynx may spread via the airways to involve the trachea, bronchi, and lung parenchyma. Squamous cell carcinoma may result. HRCT may show cysts, nodules, cavitary nodules, and endobronchial lesions (Fig. 17.4C). Papillomas may be seen within cysts.

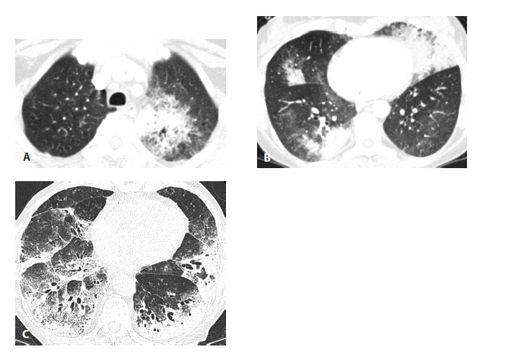

INVASIVE MUCINOUS PULMONARY ADENOCARCINOMA

Invasive mucinous adenocarcinoma (formerly diffuse bronchioloalveolar carcinoma or BAC) is a subtype of pulmonary adenocarcinoma, characterized by endobronchial spread and diffuse or multifocal lung involvement. The nonmucinous subtype of adenocarcinoma is much less likely to result in this type of dissemination; it more frequently appears as a solitary nodule, often of ground glass opacity.

The HRCT findings of invasive mucinous adenocarcinoma often resemble lobar pneumonia or bronchopneumonia. Consolidation and ground glass are the most frequent abnormalities; these abnormalities often result from filling of alveoli by mucin or fluid secreted by the tumor. The tumor itself is characterized by lepidic growth, or growth along alveolar walls, without filling or replacement of the alveolar spaces.

Abnormalities may be focal, patchy, or diffuse (Fig. 17.5). The distribution may be unilateral, bilateral, asymmetric, or symmetric. When intravenous contrast is administered, the vessels with areas of consolidation may appear dense compared with the low-density consolidation. This is called the CT angiogram sign and is common with invasive mucinous adenocarcinomas. However, this sign may be seen in many causes of consolidation and not specific for this diagnosis.

Centrilobular nodules may also be present, reflecting endobronchial spread of tumor (Fig. 17.6). Similar to bronchopneumonia, the nodules are often heterogeneous in size, with variable spread into the alveoli surrounding the centrilobular bronchiole. Nodules are most commonly of soft tissue attenuation, but ground glass opacity nodules may also be seen.

Interlobular septal thickening may be present and is typically seen in areas of ground glass opacity. This combination is termed crazy paving, and while classically associated with pulmonary alveolar proteinosis, it may be seen with a variety of other acute and chronic lung diseases.

The differential diagnosis of invasive mucinous adenocarcinoma includes infections with endobronchial spread. However, the clinical presentations of these two entities are quite different; pneumonia presents with acute symptoms and mucinous adenocarcinoma presents with chronic symptoms, usually of greater than 3 months duration. Invasive mucinous adenocarcinoma may be associated with bronchorrhea, the production of liters of watery sputum each day.

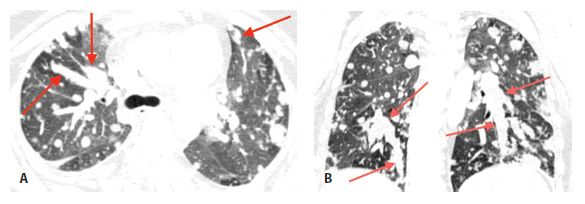

Figure 17.4

Endobronchial spread of tumor in two patients. A and B. A large central squamous cell carcinoma causes obstruction of the bronchus intermedius. B. In the same patient as (A), patchy centrilobular nodules are present in the right middle and lower lobes distal to this obstruction (arrows). These could represent post-obstructive bronchial impaction or tumor. Pathologically, there was endobronchial spread of tumor in these regions. C. In a patient with tracheobronchial papillomatosis, HRCT shows nodules (yellow arrow) and a thick-walled cavitary nodule or cyst (red arrow).

In patients presenting with chronic symptoms, the differential diagnosis of invasive mucinous adenocarcinoma includes other causes of chronic consolidation and ground glass opacity, such as organizing pneumonia, chronic eosinophilic pneumonia, sarcoidosis, lymphoma, lipoid pneumonia, and alveolar proteinosis. Centrilobular nodules are rare with these diseases and relatively common with invasive mucinous adenocarcinoma, although organizing pneumonia and sarcoidosis may rarely have associated centrilobular nodules as a prominent finding. When centrilobular nodules are absent, the various causes of chronic consolidation may be difficult to distinguish from one another.

KAPOSI’S SARCOMA

Kaposi’s sarcoma (KS) is a malignancy originally described in elderly men of Mediterranean descent, but is most frequently seen in patients with human immunodeficiency virus (HIV) infection. Pulmonary involvement is seen in up to 50% of HIV patients with KS, but its incidence has significantly declined after the development of highly active antiretroviral therapy.

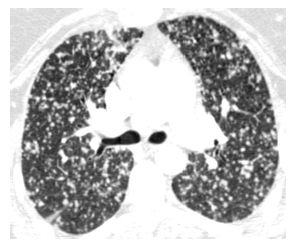

Figure 17.5

Invasive mucinous adenocarcinoma (IMA) in two patients. IMA may present with consolidation or ground glass opacity (GGO) that is focal (A), patchy, or bilateral (B). In another patient (C), IMA appears extensive and diffuse. These appearances may resemble a variety of other diseases, and IMA should always be considered in the setting of chronic consolidation and GGO.

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree