16 Neuropathic Osteo-Arthropathy of the Spine

Introduction

Neuropathic osteoarthropathy (Charcot’s) of the spine is a destructive condition of the spine secondary to a loss of the protective proprioceptive reflexes. Classically, it is due to nontraumatic causes including tabes dorsalis, syringomyelia, diabetes, mellitus, or spinal arteriovenous malformation.2,3 It can be due to central nervous (CNS) system trauma. In the majority of CNS cases, it occurs in patients who have suffered from traumatic medullary lesions and is responsible for destruction of the vertebral bodies with considerable spinal deformity. Charcot’s spine may also be found in patients with complete neurological lesions of the spinal cord. Traumatic spinal neuropathy is a condition that results as a loss of the feedback response from the desensitized components of the spine. Although spinal neuroarthropathy is a little-known complication of traumatic paraplegia,1,2 it is easy to over-look in the follow-up of such patients.

Neuropathic (Charcot’s) arthropathy of the spine is a relatively rare problem that, nonetheless, must always be considered in the differential diagnosis of any patient with degenerative lesions of one or more levels of the spine associated with diminished or absent protective sensation and significant bone destruction.

As care of spinally injured patients continues to improve, they live longer and lead a more active lifestyle. It is, therefore, expected that the incidence and prevalence of Charcot’s joints will increase. In cases of established neuro-osteoarthropathy secondary infection may also rarely complicate the clinical and radiological scenario.

Mechanism

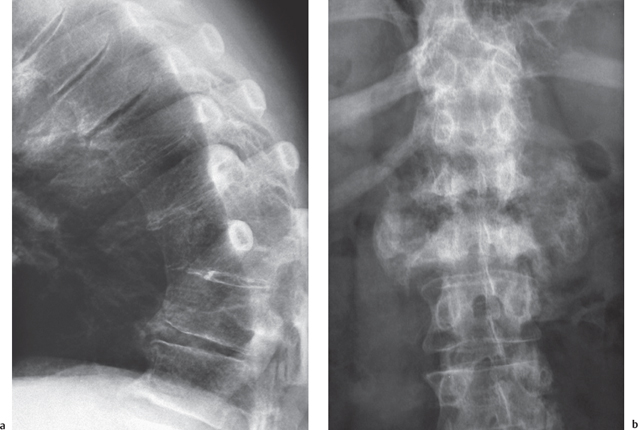

The factors predisposing patients to the development of a neuropathic joint are diminished pain and proprioceptive sensations with maintained mobility. These factors apply to the spine whether the patient is ambulant or nonambulant. The lack of proprioception and altered muscle tone lead to compromised stability of the spine and its natural curvatures. Progressive deformity of the spine (scoliosis, kyphosis, or both) appears below the traumatic level (Fig. 16.1).

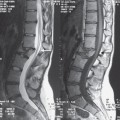

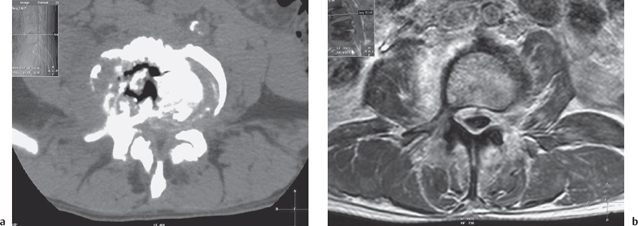

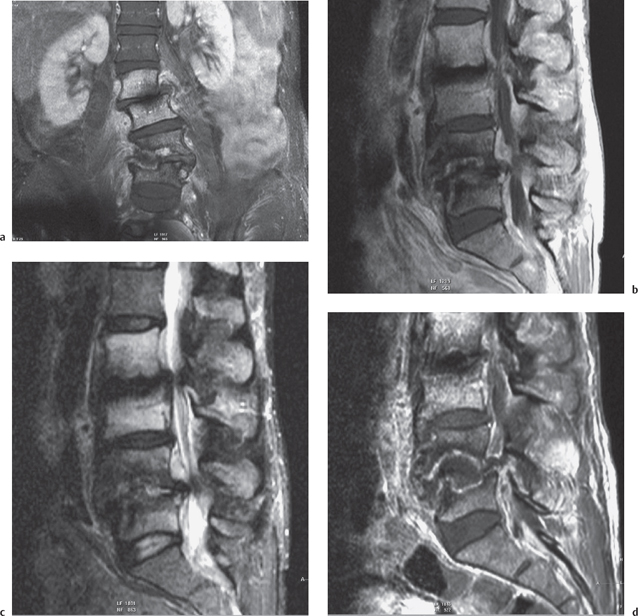

Repeated microtrauma and macrotrauma increases joint mobility beyond the normal limits, and this leads to further damage, with the process culminating in severe instability and bone destruction (Fig. 16.2). This cascade leads to failure of supporting intervertebral disks, facet joints, and ligaments resulting in subluxation, dislocation, juxta-articular bone destruction with bony fragmentation, necrosis, sclerosis, and collapse.

The disorder is characterized in both the ambulant and nonambulant patient by biological inflammation and repair reaction to recurrent injury. Neuropathic osteoarthropathy of the spine may occur in isolation or in combination with neuropathic osteoarthropathy of other joints. The thoracolumbar junction and lumbar spine are most frequently affected (Fig. 16.1), and one or more vertebral segments may be involved (Fig. 16.3). In cases of previous posterior spinal fusion with Harrington instrumentation, Charcot’s joint may occur just below the caudal end of the fusion and remote from the level of spinal cord injury.

Fig. 16.1 Plain film showing a scoliotic deformity of the spine (curvature) below a dorsal osteosynthesis for traumatic fractures.

Clinical Findings

Neuropathic changes in the spine are often silent, delaying diagnosis and treatment, or may be mistaken for infection or degenerative disease. The diagnosis was made from 6 to 31 years after original spinal cord injury in a series of post-traumatic Charcot spines.1

Clinically progressive kyphosis leading to a severe kyphotic deformity, flexion instability leading to gross instability, and loss of height are suggestive. Traumatic spinal cord injury can also produce pain and further disability. In patients having complete paraplegia with levels of neurological injury ranging from T7 to T12, the common presenting symptoms of a neuropathic spine include back pain, loss of spasticity, a change in bladder function, and audible noises with motion of the unstable segments.

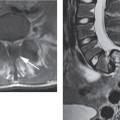

Fig. 16.3 Destructive bone changes of the lumbar spine in a 52-year-old man with traumatic paraplegia. Spinal deformity with a dislocation at the L4-L5 level. Destructive vertebral lesions at the L4-L5 level. There is marked bone marrow edema of the L2-L5 vertebral bodies and inflammatory signal changes of the perivertebral soft tissues. a Coronal fat-saturated gadolinium-enhanced T1W MRI image. L4-L5 destruction involving predominantly the right side of the disk space and vertebral endplates but also early changes are present at L2/L3 levels. b Sagittal T1W MRI image showing destruction of L4-L5. c Sagittal fat-saturated T2W MRI image showing destruction of L4-L5. Marked bone marrow edema of the L2 and L3 vertebral bodies. d Sagittal fat-saturated gadolinium-enhanced T1W MRI image. Note the rim enhancement surrounding a liquid or necrotic area in the L4/5 disk space.

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree