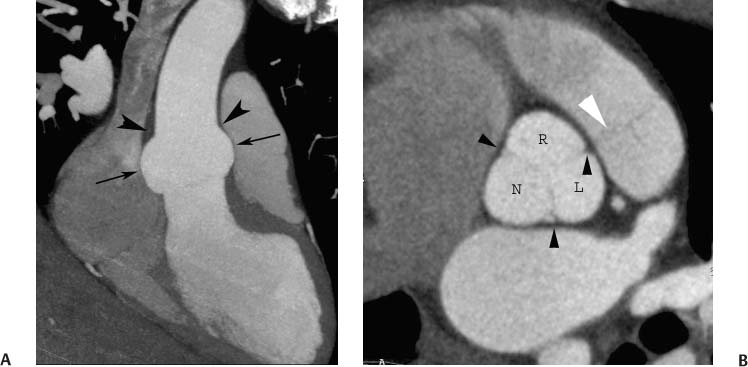

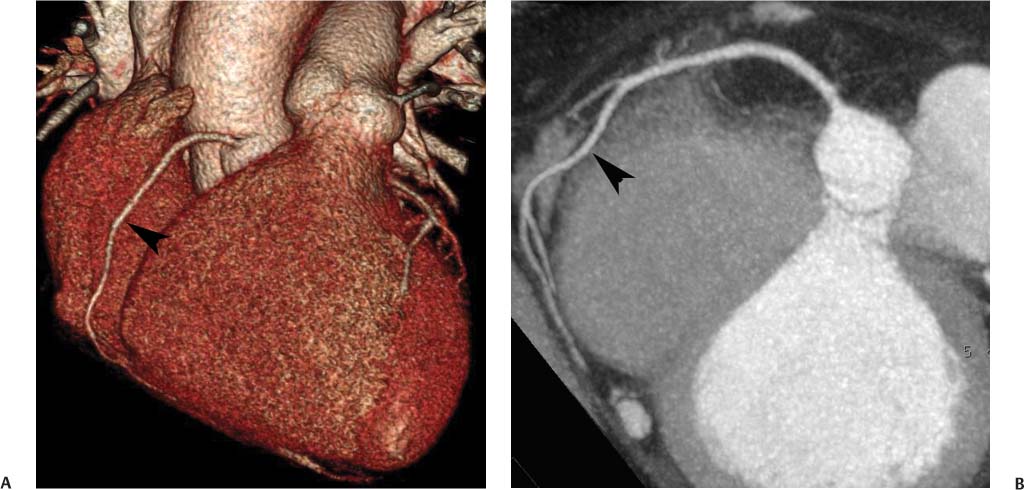

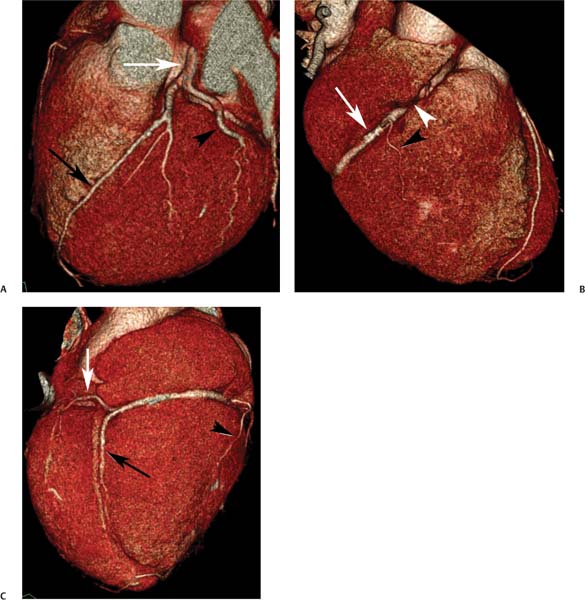

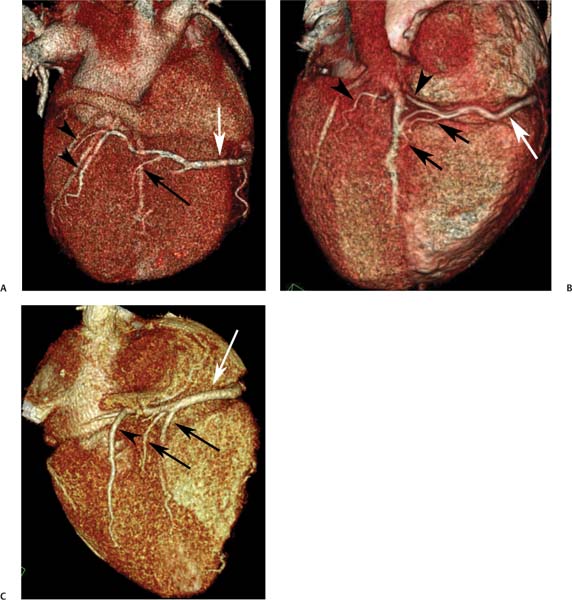

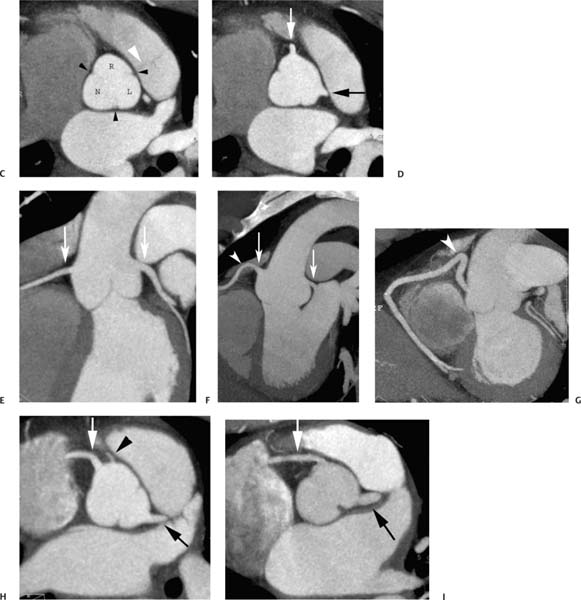

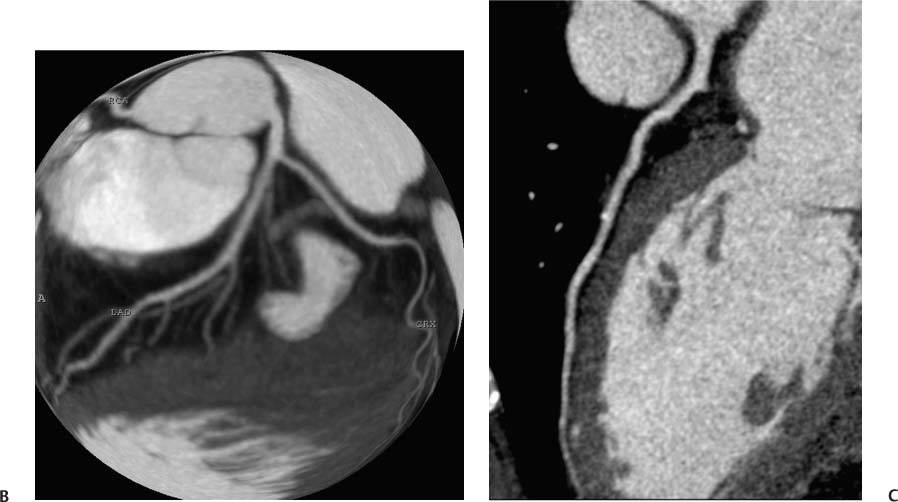

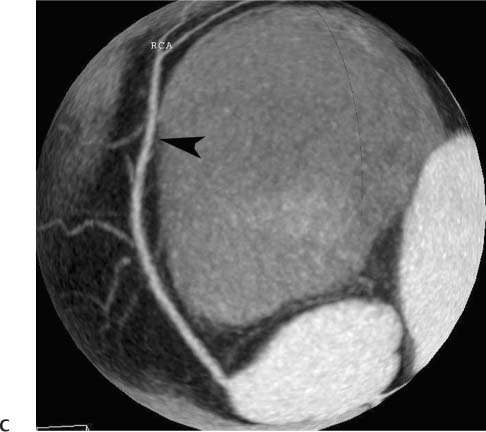

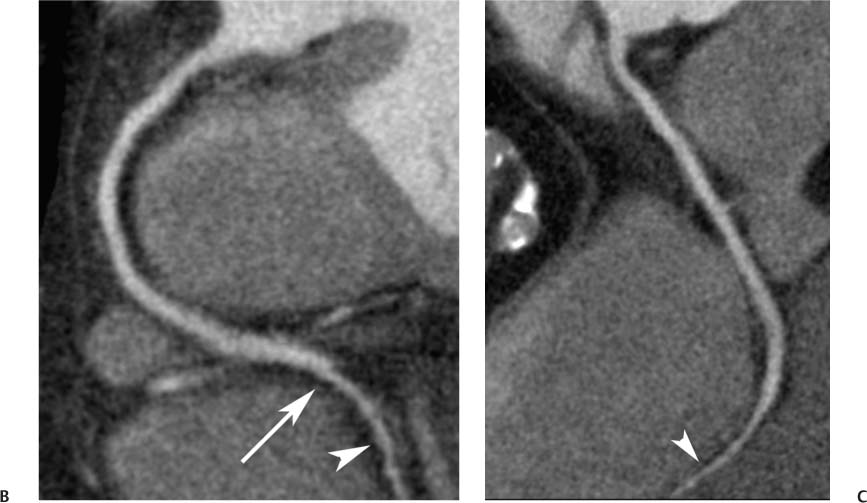

3 Coronary artery blood flow is critical for the normal development and function of the heart. Although some variations in coronary anatomy may result in cardiac dysfunction, many variations provide adequate blood flow to the myocardium. For the purposes of this chapter, however, the definition of normal coronary anatomy is based on the commonly observed anatomy rather than on an assessment of healthy versus pathologic state. In accordance with the definition of “normal” coronary anatomy by Angelini, the spectrum of normal coronary anatomy includes observed variations in coronary anatomy present in 1% or more of the population.1 Based on this criterion, less frequent variations are classified as anomalies, whether or not they result in a pathologic state. Selected coronary anomalies are discussed along with related common variants in this chapter, but most clinically significant coronary anomalies are discussed in Chapter 4. Our discussion of coronary anatomy begins with the aortic root, which extends from the aortic annulus to the sinotubular junction and consists of the aortic valve, the three sinuses of Valsalva, and the sinotubular junction. Although the tubular portion of the aorta is circular in shape beyond the sinotubular junction, the aortic root has a cloverleaf shape in short axis. Three equally spaced sites of minimal tethering within the aortic root mark the junctions of the sinuses of Valsalva (Fig. 3.1). Each sinus is associated with a leaflet of the aortic valve; the junctions between adjacent sinuses are aligned with the commissures between the aortic valve leaflets. The sinuses of Valsalva represent a normal dilation at the root of the aorta, with a diameter that is greater than that in the tubular portion of the ascending aorta. Fig. 3.1 Aortic root, including aortic valve, sinuses of Valsalva, and sinotubular junction. (A) Sagittal maximum intensity projection (MIP). There is a normal dilatation of the aortic root related to the sinuses of Valsava (arrows). The sinotubular junction is marked by a caliber change just above the aortic root (arrowheads). (B) Axial MIP at the level of the aortic valve. The root demonstrates a cloverleaf shape with three sinuses of Valsalva named for their coronary arteries: R, right, L, left, and N, noncoronary. The commissures of the aortic valve are visible (black arrowheads) as is the pulmonary valve (white arrowhead). The commissure between the right and left aortic leaflets is aligned with an adjacent commissure in the pulmonic valve. Aortic root, including aortic valve, sinuses of Valsalva, and sinotubular junction. (C) Axial MIP at a slightly higher level again demonstrates the cloverleaf shape of the aortic root. (D) Axial MIP just below the sinotubular junction demonstrates normal origins of the coronary arteries from the center of the right (white arrow) and left (black arrow) coronary sinuses. (E) Slab MIP in the left anterior oblique projection. The right (RCA) and left (LCA) coronary arteries originate from the sinuses of Valsava, just below the level of the sinotubular junction (arrows). (F) The coronary origins in a different patient demonstrate a shepherd’s crook curvature of the proximal RCA (arrowhead). A shepherd’s crook proximal RCA is a common variation (approximately 5%) that may present as a technical challenge during angioplasty. (G) Slab MIP of the RCA in another patient with a more obvious shepherd’s crook (arrowhead). (H) Axial MIP in a patient with independent origins of the conus artery (black arrowhead) and RCA (white arrow). The origin of the RCA is shifted toward the right, while the conus artery and the LCA (black arrow) originate from the center of their respective sinuses. (I) Axial MIP in a patient with bicuspid aortic valve. Only two sinuses of Valsalva are present. Both coronary arteries arise from the anterior-left sinus. The RCA (white arrow) originates at an acute angle from the aortic root. The proper anatomic names for the three sinuses of Valsalva are the posterior, right, and left sinuses. The common names for the sinuses—noncoronary sinus, right coronary sinus, and left coronary sinus—refer to the coronary arteries, which normally originate from the center of two of the sinuses. The right coronary artery (RCA) originates from the more anterior right sinus of Valsalva, and the left coronary artery (LCA) originates from the left sinus of Valsalva. The coronary arteries originate from the superior portions of the sinuses of Valsalva, just below the sinotubular junction. The ostia of the arteries are located just above the free margins of the aortic leaflets during systole. A normal coronary artery origin is situated at a right angle to the wall of the aortic root. Coronary ostia that arise at an acute angle are typical of anomalous vessels, described in more detail in Chapter 4. The right ventricular outflow tract is normally located anteriorly and to the left of the aortic root. During embryologic development, the pulmonary artery separates from the aortopulmonary truncus. The commissure between the right and left cusps of the aortic valve is aligned with the posterior commissure of the pulmonic valve. The alignment of these two commissures is related to the origin of both valves from the aortopulmonary truncus. The commissure between the right and left coronary sinuses within the aortic root remains adjacent to the embryologic aortopulmonary septum. During embryologic development, the infundibulum is resorbed below the aortic valve but is preserved within the right ventricular outflow tract. This resorption results in caudal displacement of the aortic annulus relative to the pulmonic valve. To maintain its relationship with the pulmonary artery, the aortic annulus becomes angled off the axial plane such that the aortopulmonary contact point remains the most superior point within the aortic root. The coronary arteries arise on both sides of this contact point (the embryologic aortopulmonary septum) from the right and left coronary sinuses. As a result of this angulation of the aortic root out of the axial plane, the proximal coronary arteries are often directed superiorly. Anomalies of septation of the aorta and pulmonary artery—tetralogy of Fallot, truncus arteriosus, pulmonary atresia, and transposition—are often associated with anatomic variations in coronary anatomy.2–5 The left main coronary artery typically originates as a single vessel from the left sinus of Valsalva. This artery courses between the right ventricular outflow tract and the left atrium and under the left atrial appendage (Fig. 3.2). To visualize the left main coronary artery on surface-rendered images of the heart, the left atrial appendage must be removed. As the left main coronary artery emerges from under the left atrial appendage, it typically divides into two major branches: the left anterior descending (LAD) artery and the circumflex (LCX) artery. The LAD courses in the epicardial space along the anterior interventricular groove between the right and left ventricles down to the apex of the heart. The LAD supplies blood flow to the interventricular septum through the anterior septal perforators and to the anterior and anterolateral walls of the left ventricle through diagonal branches. Septal branches are often difficult to visualize with coronary CT angiography (CTA) because of their small size as well as the enhancement of the surrounding septal myocardium. Diagonal branches course in the epicardial space over the left ventricular free wall and are more readily visible on coronary CTA. The LAD may end slightly before the apex, or it may wrap around the apex into the posterior interventricular groove. The LCX courses in the left atrioventricular groove between the left atium and left ventricle. The LCX provides flow to the lateral and posterior lateral walls of the left ventricle through obtuse marginal branches. The LCX and obtuse marginal arteries are epicardial in location and generally well visualized on coronary CTA. The extent of myocardial territory supplied by the LCX is highly variable. The LCX may end as an obtuse marginal branch. In a minority of people, the circumflex artery courses around the left atrioventricular groove to the crux of the heart and supplies the posterior descending artery (PDA). The crux is defined as the point on the diaphragmatic surface of the heart where the right atrioventricular groove, the left atrioventricular groove, and the posterior interventricular groove converge. The PDA courses along the posterior interventricular groove from the crux to the cardiac apex. The RCA courses within the right atrioventricular groove, between the right atrium and right ventricle, where it supplies small acute marginal branches to the free wall of the right ventricle (Fig. 3.3). The proximal portion of the RCA is often covered by the right atrial appendage. The RCA is often embedded within a deep right atrioventricular groove but is generally well visualized because of its epicardial location. In most people, the RCA continues around the right atrioventricular groove to the crux of the heart, where it supplies a PDA that descends in the posterior interventricular groove (Fig. 3.4). The PDA supplies numerous small branches into the septum, the posterior septal perforating arteries. The RCA generally continues beyond the crux of the heart to supply additional posterior left ventricular branches. In the setting of coronary disease, the posterior septal perforating arteries may collateralize with the LAD via the anterior septal perforators, and the posterior left ventricular branches may collateralize with the LCX via distal obtuse marginal branches. Fig. 3.2 Left coronary artery anatomy. (A) Volumetric surface rendering demonstrates the course of the left main coronary artery between the right ventricular outflow tract (RVOT) and left atrium (LA). The left main coronary artery bifurcates into the left anterior descending (LAD) (black arrow) and circumflex (white arrow) arteries. A diagonal branch (black arrowhead) arises from the LAD. The circumflex terminates as an obtuse marginal branch (white arrowhead). Left coronary artery anatomy. (B) Globe MIP of the same patient demonstrates the LAD in the anterior interventricular groove and the circumflex in the left atrioventricular groove. (C) Curved MIP demonstrates the entire length of the LAD as it courses along the anterior interventricular groove to the apex of the left ventricle. Fig. 3.3 Right coronary anatomy in surface and maximum intensity projections (MIPs). (A) Surface image in a shallow left anterior oblique (LAO) projection demonstrates the right coronary artery (RCA) (black arrowhead) coursing along the right atrioventricular (AV) groove. (B) MIP image in the LAO projection again demonstrates the RCA (black arrowhead), coursing in a classic “C” shape toward the crux of the heart. In this patient, the RCA bifurcates into the posterior descending artery and a posterior left ventricular branch proximal to the crux. (C) Globe MIP demonstrates the RCA (black arrowhead) within the AV groove adjacent to the right atrium. Fig. 3.4 Right coronary artery (RCA) and posterior descending artery (PDA) in surface and maximum intensity projections (MIPs). (A) The RCA courses in the right atrioventricular groove (arrow) to the crux of the heart. The PDA arises from the RCA at the crux and courses down the posterior interventricular groove (arrowhead). Right coronary artery (RCA) and posterior descending artery (PDA) in surface and maximum intensity projections (MIPs). (B) The classic “C” shape of the RCA is demonstrated in a curved MIP LAO projection. The vessel narrows in caliber at the crux of the heart (arrow), where it bifurcates into the PDA (arrowhead) and posterior left ventricular branches (not shown). (C) Orthogonal MIP image again demonstrates the RCA throughout its course to the PDA. A commonly described variation in coronary anatomy is the degree to which the left ventricular myocardium is supplied by the LCA and RCA. Coronary dominance refers to the supply of the PDA and the posterior left ventricular branches. In a right-dominant system, the RCA supplies the PDA as well as additional posterior left ventricular branches (Fig. 3.5). In a superdominant right circulation, the LCX is very small and the RCA continues to supply the posterior and lateral wall of the left ventricle (Fig. 3.6). In a left-dominant system, the LCX supplies the posterior left ventricular branches as well as the PDA (Fig. 3.7). In the setting of a wraparound LAD, the LAD may actually supply the PDA in a left-dominant circulation (Fig. 3.7). In a balanced circulation, the RCA supplies the PDA, and the circumflex supplies the posterior left ventricular branches (Fig. 3.8). A right-dominant circulation is present in the vast majority of the population. In one study of 1950 people, right dominance was observed in 89.1%, left dominance in 8.4%, and codominance in 2.5%.6,7 Right-dominant, left-dominant, and codominant circulations all represent normal variations of the coronary arterial tree. Of note, the term right-dominant system is somewhat of a misnomer because the left main coronary artery and its branches almost always supply most of the blood flow to the left ventricle, even in the presence of a right-dominant system. Fig. 3.5 Normal right-dominant coronary circulation. (A) Surface-rendered image in a steep left anterior oblique (LAO) projection demonstrates the bifurcation of the left main coronary artery (white arrow) into the left anterior descending (black arrow) and circumflex (black arrowhead) arteries. (B) Right anterior oblique projection demonstrates the right coronary artery (RCA) (arrow) as it courses in the right atrioventricular groove. The proximal portion of the RCA is obscured by the overlying right atrial appendage (white arrowhead). A small acute marginal branch of the RCA is demonstrated (black arrowhead). (C) The heart is rotated further so that the crux is visible. The distal RCA bifurcates into the posterior descending artery (black arrow), which courses in the posterior interventricular groove and a posterior left ventricular branch (white arrow). An acute marginal branch is again identified (black arrowhead). Fig. 3.6 Right-dominant circulation in three different patients. (A) Surface rendering at the crux of the heart demonstrates the bifurcation of the right coronary artery (white arrow) into a posterior descending artery (black arrow) and posterior left ventricular branches (black arrowheads). These branches arise from the right coronary artery in a right-dominant circulation. (B) Surface rendering at the crux of the heart in a second patient demonstrates the bifurcation of the right coronary artery (white arrow) into a duplicated posterior descending artery (black arrows) and a large posterior left ventricular branch (black arrowhead). (C) Surface rendering at the crux of the heart in a third patient demonstrates the bifurcation of the right coronary artery (white arrow) into a duplicated posterior descending artery (black arrows) and a large posterior left ventricular branch (black arrowhead).

Normal Coronary Anatomy

Aortic Root

Aortic Root

Main Coronary Arteries

Main Coronary Arteries

Coronary Dominance

Coronary Dominance

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree