New Target Delineation Contours

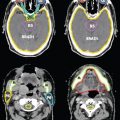

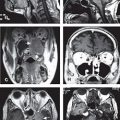

FIGURE 7-7. CTV1, CTV2, and CTV3 delineation in a patient with left mandibular squamous cell carcinoma post left hemimandibulectomy, left neck dissection, tracheotomy, and reconstruction with fibular free flap, pathologically T4aN0, who received postoperative IMRT.

1. ANATOMY

• The oral cavity consists of the upper and lower lips, gingivobuccal sulcus, buccal mucosa, upper and lower gingiva (including alveolar ridge), hard palate, floor of the mouth, and anterior two-thirds of the tongue.

• The lips are the anterior border of the oral cavity. The vermilion border is the site of transition between facial skin and oral mucous membrane. Sensory nerves to the upper lip are provided by the infraorbital branch of the maxillary nerve (V2), while lower lip sensation is provided by the mental nerve (V3).The labial arteries are branches from the facial artery and provide the main blood supply to the lips.

• The upper and lower alveolar ridges are covered by the gingiva and contain the alveoli (sockets) of the teeth. Lateral to each alveolar ridge is the gingivobuccal sulcus, the transition from the alveolus to the buccal mucosa. Medially, the upper alveolus transitions to the hard palate while the lower alveolus transitions to the floor of the mouth. The upper alveolar ridge extends posterosuperiorly to the maxillary tuberosity and the lower alveolar ridge continues posteriorly to the retromolar trigone, which is the mucosa overlying the ascending ramus of the mandible. The retromolar trigone is a small triangular region that is continuous with the buccal mucosa laterally and the anterior tonsillar pillar medially. Sensory innervation of the upper alveolus and maxillary teeth is provided by the alveolar nerves (V2), as well as the greater palatine and nasopalatine nerves. The lower alveolus and mandibular teeth receive sensory innervation from various branches of the mandibular nerve (V3). The blood supply to the alveolar ridges is provided by the branches of the internal maxillary artery.

• The tongue is a muscular organ composed of intrinsic and extrinsic muscles which are separated within the midline by a fibrous lingual septum. The sulcus terminalis, situated posterior to the V-shaped configuration of the circumvallate papillae, separates the oral tongue (anterior two-third) from the base of the tongue (posterior one-third). Four extrinsic muscles (genioglossus, hyoglossus, styloglossus, and palatoglossus) serve to move the position of the tongue. The hypoglossal nerve (CN XII) provides motor innervation to all the musculature of the tongue except to the palatoglossus, which is innervated by a pharyngeal branch of the vagus nerve (CN X). The general sensory nerve of the oral tongue is the lingual nerve, a branch of the mandibular nerve (V3). The chorda tympani provides specialized taste sensation to the oral tongue. It branches from the facial nerve, before the latter exits the stylomastoid foramen, and joins the lingual nerve to provide special sensory fibers to the anterior two-third of the tongue. It also provides parasympathetic innervation to the tongue and submandibular and sublingual glands via the submandibular ganglion. The base of tongue receives both general and special taste sensation innervation from the glossopharyngeal nerve (CN IX). The primary blood supply to the tongue comes from the lingual artery.

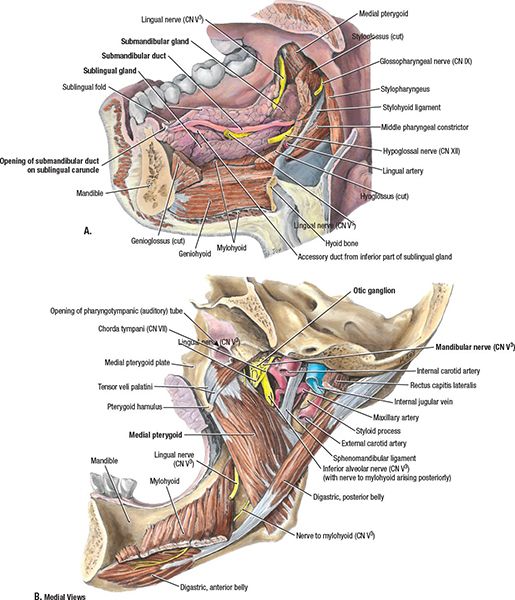

• The floor of the mouth is bounded by the lower gingiva anteriorly and laterally, and extends posteriorly to the insertion of the anterior tonsillar pillar into the tongue (Fig. 7-1). The floor of the mouth is divided into halves by the lingual frenulum and is covered by a mucous membrane with stratified squamous epithelium. A muscular sling, composed of the genioglossus, mylohyoid, and hyoglossus, supports the contents of the floor of the mouth space. The sublingual glands lie just below the mucosa superomedial to the mylohyoid muscle and adjacent to the lingual surface of the anterior mandible. The sublingual space is continuous with the submandibular space at the posterior margin of the mylohyoid. The submandibular glands consist of a larger superficial portion that lies primarily in the submandibular space inferior to the mylohyoid muscle and a smaller, deep portion located superior to the mylohyoid in the sublingual space. The submandibular duct (Wharton’s duct) arises from the deep portion of the gland, courses between the sublingual gland and genioglossus muscle, and opens in the anterior floor of the mouth just lateral to the lingual frenulum. The lingual nerve provides sensory innervation to the floor of mouth. While the hypoglossal nerve provides motor innervation to the tongue, not to the muscles in the floor of mouth, it is important to note its location, as it runs just inferior to the hyoglossal fascia. The lingual artery, a branch of the external carotid artery, supplies blood to the floor of the mouth.

• The hard palate extends from the posterior aspect of the upper alveolar ridge to the soft palate and serves as the roof of the mouth separating the oral and nasal cavities. The bony portion of the hard palate is composed of the palatine process of the maxilla and the horizontal plate of the palatine bone, and is covered by tightly adherent periosteum and mucosa. The incisive foramen, which is located immediately posterior to the maxillary incisors, transmits the nasopalatine nerve (V2) from the floor of the nasal cavity as well as the nasopalatine artery, a branch of the sphenopalatine artery, supplying the oral mucosa covering the hard palate. The greater and lesser palatine foramina are located at the posterolateral aspect of the hard palate directly anterior to the junction of the hard and soft palate; these foramina transmit the greater and lesser palatine vessels and nerves.

• The buccal mucosa is the mucous membrane overlying the internal surface of the lips and cheeks, extending from the posterior portion of the lips medially to the upper and lower alveolar ridges and posteriorly to the pterygomandibular raphe and retromolar trigone. The papillae of the parotid duct (Stensen’s Duct) open into the vestibule of the mouth at the level of the second maxillary molar after exiting the parotid gland and piercing through the buccal fat, buccopharyngeal fascia, and buccinator muscle. The masseter muscle lies posteriorly and laterally to the buccinator muscle. The blood supply comes from the facial artery. Sensory innervation to the buccal mucosa is provided by the second and third branches of the trigeminal nerve (V2 and V3), and the facial nerve provides motor innervation to the buccinator muscle.

FIGURE 7-1. Muscles, glands, and vessels of floor of mouth and medial aspect of mandible. (A) Sublingual and submandibular glands. The tongue has been excised. (B) Structures related to the medial surface of the mandible. The optic ganglion lies medial to the mandibular nerve (CN V3) and between the foramen ovale superiorly and the medial pterygoid muscle inferiorly. (From Agur AMR, Dalley AF. Grant’s Atlas of Anatomy, 12th ed. Philadelphia, PA: Lippincott Williams & Wilkins, 2009:681.)

2. NATURAL HISTORY

• Oral cavity cancers typically begin as exophytic masses, ulcers, or patches of thickened white or red areas within the mouth which persist for more than 2 weeks. These lesions may be asymptomatic or may be painful and may bleed easily. Due to the close proximity of the oral mucosa to the underlying bone throughout many areas within the oral cavity, such as the alveolar ridge, early bone invasion is not uncommon. A graphic illustrating oral cavity cancer spread is shown in Figure 7-2.

• Lip cancers are often detected at an early stage with no cervical metastasis because of their prominent, visible location.

• Oral tongue cancers mainly originate from the lateral and ventral surfaces of the tongue and are often diagnosed in early stages. Advanced lesions may grow into the adjacent structures within the oral cavity or oropharynx, such as the anterior tonsillar pillar, floor of the mouth, and base of the tongue. In addition, as there are no distinct planes between the intrinsic muscles of the tongue, a diffusely infiltrating pattern of tumor growth may develop. Perineural invasion of the lingual or hypoglossal nerves can also occur. Studies have shown that tumor thickness of >4 mm, and not just T stage, correlates with increased risk of occult cervical metastasis as well as with reduced survival.1,2

• Floor of the mouth cancers mostly originates within 2 cm of the anterior midline. There is early invasion into the submucosa, with extension into the sublingual glands as well as into the genioglossus and geniohyoid muscles. The muscular sling of the floor of mouth, composed of the genioglossus, mylohyoid, and hyoglossus muscles, serves as a barrier to the spread of disease in the early stages. As the tumor growth progresses, there can be invasion into the muscles of the floor of mouth, oral tongue, and lower alveolar ridge. Small and early lesions may extend into the periosteum, but mandible invasion occurs late in the course of the disease. Perineural invasion into the lingual or hypoglossal nerves can lead to the loss of sensation along the dorsal surface of the tongue, as well as deviation of tongue protrusion, fasciculations, and muscular atrophy. Submandibular ducts may become obstructed. Approximately one-third of patients have cervical lymph node involvement, with the submandibular nodes most commonly involved.

FIGURE 7-2. Patterns of spread. (A) Coronal view: The invasion of oral tongue cancer into floor of mouth and alveolar ridges. (B) Sagittal view: The invasion of oral tongue cancer into extrinsic floor of mouth musculature and posterior tongue. The primary cancer (oral cavity) invades in various directions, which are shown as color-coded vectors (arrows) representing stages of progression: Tis, yellow; Tl, green; T2, blue; T3, purple; T4A, red; and T4B, black. (From Rubin P, Hansen JT. TNM Staging Atlas with Oncoanatomy, 2nd ed. Philadelphia, PA: Lippincott Williams & Wilkins, 2012:53. Modified from Agur AMF, Dalley AF, eds. Grant’s Atlas of Anatomy, 12th edition. Philadelphia: Lippincott Williams & Wilkins, 2009.)

• Retromolar trigone cancers typically are diagnosed only in advanced stages. The mucosa is tightly adherent to the underlying mandible, allowing for malignant tumors to infiltrate the periosteum of the mandible at an early stage. Invasion of the underlying mandible may be an early or late manifestation. The lingual nerve enters the mandible just posteromedial to the retromolar trigone and may become involved with the tumor relatively early. Lower lip paresthesia may be an indication of perineural invasion at the level of the mandibular foramen. Lesions commonly spread to the adjacent buccal mucosa, anterior tonsillar pillar, and lower alveolus. Retromolar trigone lesions have an overall metastasis rate of approximately 45%.3

• Buccal mucosa lesions typically develop on the lateral walls, often adjacent to the third mandibular molar. Advanced lesions can invade the muscles of mastication and may eventually penetrate laterally to the skin or superiorly to the infratemporal fossa. Advanced lesions may also extend into the parotid gland causing obstructive sialadenitis and facial nerve dysfunction.

3. DIAGNOSIS AND STAGING SYSTEM

3.1. Signs and Symptoms

• Lesions of the lip are typically nonhealing blisters or ulcers on the vermilion or cutaneous skin. Sclerotic or nodular lesions may penetrate deeper into the soft tissue.

• Oral tongue carcinomas may present as an exophytic mass or ulceration. Irritation and the sensation of a lump are the most frequent symptoms in tongue cancer. Pain is typically localized, but lingual nerve involvement can present with referred otalgia via the auriculotemporal nerve. More advanced lesions, including base-of-tongue extension, may cause referred otalgia via Jacobson’s nerve (CN IX). Speech and swallowing may be affected in advanced lesions. Bleeding may occur.

• Floor of the mouth lesions often present early as a lump. Bleeding, loose teeth, halitosis, a painful mass in the submandibular region, change in speech, restricted tongue mobility or fixation, and loss of sensation along the dorsal surface of the tongue, as well as deviation of tongue protrusion, fasciculations, and muscular atrophy can be seen in advanced lesions.

• Alveolar lesions are typically ulcerative, while hard palatal lesions can present as a submucosal nodule or an ulcerative mass. These lesions are often asymptomatic in the early stages, but can become painful as the disease advances. Ill-fitting dentures, bleeding, and halitosis can be associated with progress of the disease. Tumor extension from the lower alveolar ridge can invade the inferior alveolar nerve, causing paresthesia of the mandibular teeth and chin. Direct bony infiltration of the hard palate can extend up into the nasal cavity or maxillary sinus, and may invade the greater palatine nerve causing paresthesia of the palate.

• Retromolar trigone lesions can produce local pain and referred pain to the external auditory canal and preauricular area. Trismus may be seen if the lesion invades the medial pterygoid muscles. Hyperesthesia may indicate perineural invasion.

• Buccal mucosa tumors often have associated leukoplakia. Obstruction of Stensen’s duct may cause swelling and/or inflammation of the parotid gland. Extension into the pterygoids, masseter, or buccinator muscles may cause trismus. Intermittent bleeding can be seen during mastication.

3.2. Physical Examination

• The extent of disease in oral cavity lesions is determined by visual examination and palpation. It is imperative to remove dentures and oral appliances for a thorough evaluation. Topical anesthesia may be required for examination.

• Bimanual palpation determines the extent of induration and degree of fixation to the periosteum. Large lesions bulge into the submental or submandibular space. The submandibular duct and gland, as well as the parotid duct and gland, are evaluated by bimanual palpation.

3.3. Imaging

3.3.1. Floor of the Mouth

• On axial imaging, the floor of the mouth is seen as a fat-containing space lying between the paired bellies of the genioglossus and geniohyoid muscles. The mylohyoid muscle is best seen on coronal sections because it extends from the mylohyoid line of the mandible to the hyoid.

• The sublingual spaces are usually symmetric. The submandibular space is separated from the floor of the mouth by the mylohyoid muscle and is located in the suprahyoid part of the neck. The sublingual space communicates with the submandibular space at the posterior extent of the mylohyoid. Because these spaces contain glandular and fat tissue, they are easily distinguished from adjacent muscles on both CT and MRI. The lingual vessel bundle is easily identified in these spaces with contrast. The hypoglossal and lingual nerves are normally difficult to identify.

• The hyoglossus muscle is visible on axial and coronal images coursing within the glandular and fatty tissue of the sublingual space.

• The small space between the digastric muscles next to their insertion on the mandible is the submental space. The submandibular space contains the submandibular gland, facial vessels, and lymph nodes, which are normally small (<5 mm). Floor-of-the-mouth lesions can obstruct the ducts, leading to submandibular ductal dilatation and subsequent gland swelling/inflammation which should be distinguished from gland invasion on imaging.

3.3.2. Oral Tongue

• It is difficult to differentiate the zone between the floor of the mouth and the ventral surface of the oral tongue in axial images. Coronal or sagittal sections of MRI or CT are better in evaluating floor-of-the-mouth invasion. Careful imaging may also aid in identification of extension across the midline lingual septum. In the sagittal plane of MRI, various intrinsic muscle bundles and fat tissue can easily be seen. The styloglossus muscle interdigitates with the hyoglossus muscle within the posterior aspect of the tongue.

• The muscles and spaces medial and lateral to the styloglossus muscle are potential places of tumor spread toward the skull base from the floor of the mouth and tongue base.

• Although CT and MRI cannot detect microscopic spread beyond the visible margins of the tumor, they are critical in helping to map the gross tumor boundary before surgical management or radiation therapy.

3.3.3. Retromolar Trigone

• CT is the choice of imaging because a detailed study of bony structures, soft tissues, and regional nodes is required. Spread to the lingual muscles can be recognized better on MRI than on CT. Occult spread anteriorly along the attachment of the mylohyoid muscle may be visible on CT or MRI when not palpable or visible by clinical examination. Supplemental MRI may be useful when looking for perineural spread and determining extension into the nasal cavity or soft palate.

3.4. Staging

• In 2010 the American Joint Committee on Cancer issued new TNM classification guidelines for Lip and Oral Cavity cancers.4 One significant change from the 6th edition is that T4 lesions have been subdivided into T4a and T4b for moderately and very advanced disease, respectively. The reader is encouraged to consult the new AJCC staging manual for details.

4. RISK FACTORS FOR NODAL METASTASIS

• Clinically detected nodal metastases on admission vary according to T stage and subsites of the oral cavity (Table 7-1). The incidence and distribution of metastatic disease in clinically negative and positive neck nodes also change according to subsites of cancer in the oral cavity. The distribution of pathologically positive neck nodes after electively modified neck dissection in patients with carcinomas in the oral tongue, floor of the mouth, or retromolar trigone is shown in Tables 7-2 through 7-4.

• There are several factors influencing contralateral nodal metastasis in oral cavity cancer (Table 7-5

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree