Risk assessment tools

Clinical presentation and history

Risk factors, nature of chest pain

Physical examination

Anemia, blood pressure, heart failure, arrhythmias

Chest X ray

Cardiomegaly, left ventricular failure

ECG

12 lead, dynamic monitoring, exercise ECG

Echo

Bedside echo, stress echo, and contrast echo

Biomarkers

Creatinine kinase, creatinine kinase-myoglobin, troponin (I and T), BNP, NT-proBNP, hsCRP

Assessment of coronary anatomy

Coronary CT angiography, invasive coronary angiography

Ideal Timing for Intervention

Timing of intervention for NSTE-ACS continues to be a hotly debated topic. As mentioned earlier, vulnerable plaque results in variable degrees of coronary arterial occlusion and is responsible for the varied presentation from mild chest pain (usually at rest) to severe ongoing chest pain with ST-segment depression, rather than ST elevation (unlike STEMI). It can be argued that patients who do not have ongoing pain, hemodynamic compromise, or dynamic ECG changes do not need to be rushed to the cath lab on presentation. Recent data and meta-analyses have helped the development of protocols and guidelines. The timing of intervention in randomized studies has varied from as early as 12 h and the major randomized studies are depicted in Table 4.2.

Table 4.2

Major randomized studies with early and delayed interventional strategies in ACS

Study | N | Arms | Outcomes | Result |

|---|---|---|---|---|

FRISC II [31] | 2,457 | Invasive (<10 days) vs. conservative | Death/MI at 12 months | 10.4 % vs. 14.1 % P = 0.005 |

TACTICS TIMI [32] | 2,220 | Early invasive (median 25 h) vs. selective invasive (median 93 h) for PCI | Death/MI/readmission at 6 months | 9.4 % vs. 15.9 % P = 0.025 |

RITA 3 [33] | 1,890 | Early invasive (median 3 days to PCI) vs. conservative | Death/MI/refractory angina at 12 months | 9.6 % vs. 14.5 p = 0.001 |

ICTUS [34] | 1,200 | Early invasive (median 23 h) vs. selective invasive (median 283 h) | Death/MI/readmission with ACS at 12 months | 22.7 % vs. 21.2 % P = 0.35 |

TIMACS [35] | 3,031 | Early invasive (median time 16 h to PCI) vs. delayed invasive (median time 52 h to PCI) | Death/MI/stroke at 6 months | 9.6 % vs. 11.3 % p = 0.15 |

A collaborative meta-analysis of seven randomized controlled trials of routine versus selective intervention strategy by Mehta et al. [36] that included over 9,000 patients found that at 17 months follow-up, the routine invasive strategy was associated with a reduction in MI, severe angina, and rehospitalizations compared to selective intervention strategy. However, they also found that routine intervention was associated with a higher early mortality (1.8 % during initial hospitalization compared to 1.1 % in selective intervention group). This highlighted the importance of risk stratification as patients in the higher-risk groups derived greater absolute benefit from a routine invasive strategy.

A meta-analysis of individual subjects of three randomized studies (RITA 3, FRISCII, and ICTUS) at 5 years follow-up [37] reports a significant reduction in the composite of death and myocardial infarction with routine invasive treatment (14.7 % vs. 17.9 % with selective intervention) driven primarily by reduction in MI. The absolute reduction in cardiovascular death or MI was 2.0 % in the low-risk, 3.8 % in the intermediate-risk, and 11.1 % in the high-risk groups emphasizing again that high-risk groups have the most to gain with a routine intervention strategy.

A recent meta-analysis by Katritsis et al. [38] which included 4,013 patients from the ABOARD, ELISA, ISAR-COOL, and TIMACS study concludes that although early intervention did not reduce the risk of death or myocardial infarction, there was a significant reduction in the risk of recurrent ischemia and the duration of hospital stay.

The ESC guidelines [7] therefore recommend an early intervention strategy within 24 h of admission for high-risk groups (GRACE score >140) and angiography and revascularization in the same admission (preferably within 72 h) for the low-risk groups. The NICE guidelines [39] recommend 96 h as the timeframe to perform angiography and revascularization on the basis that data from randomized trials reflect time from randomization to intervention rather than from presentation.

STEMI

Reperfusion therapy has been recognized as highly beneficial for patients with STEMI (Fig. 4.1). It is indicated in all patients with history of chest pain/discomfort of <12 h and with persistent ST-segment elevation or (presumed) new left bundle branch block. Guidelines recommend reperfusion in patients with ST elevation even after 12 h of symptom onset if there is ongoing ischemia (clinical or ECG). PCI of a totally occluded artery >24 h after symptom onset in a stable patient is however not recommended. Fibrinolysis studies have consistently demonstrated mortality and morbidity benefits, and it has been well recognized that “time is muscle.”

Primary PCI (PPCI) has emerged as the gold standard treatment in recent years, and both the ESC and the American guidelines recommend PPCI where feasible and when the PPCI can be undertaken within the relatively tight guideline mandated times. PPCI can also be performed in patients in whom fibrinolysis is contraindicated due to any of the causes mentioned in Table 4.3, although mortality and morbidity is higher in this cohort [40].

Table 4.3

Contraindications to fibrinolysis

Absolute contraindications |

Hemorrhagic stroke or stroke of unknown origin at any time |

Ischemic stroke in preceding 6 months |

Central nervous system trauma or neoplasms |

Recent major trauma/surgery/head injury (within preceding 3 weeks) |

Gastrointestinal bleeding within the last month |

Known bleeding disorder |

Aortic dissection |

Noncompressible punctures (e.g., liver biopsy, lumbar puncture) |

Relative contraindications |

Transient ischemic attack in preceding 6 months |

Oral anticoagulant therapy |

Pregnancy or within 1 week postpartum |

Refractory hypertension (systolic blood pressure 180 mmHg and/or diastolic blood pressure 110 mmHg) |

Advanced liver disease |

Infective endocarditis |

Active peptic ulcer |

Refractory resuscitation |

Selecting Patients for PCI When They Have Been Given Fibrinolysis

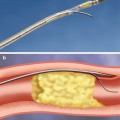

Reperfusion therapy initiated prior to planned PCI for STEMI in order to bridge the time gap is defined as facilitated PCI. A variety of agents have been used like full-dose or half-dose fibrinolytics and GPIIb/IIIa inhibitors, and results were not consistent [41, 42], and facilitated PCI is not recommended by the 2008 ESC guidelines (class III) since it is not better and may be worse than PPCI (Fig. 4.2).

Pharmacoinvasive strategy on the other hand is defined as pharmacological reperfusion with an invasive strategy backup where patients are transferred to a PCI-capable hospital after being administered fibrinolytic therapy, following which they undergo rescue PCI if they have failed to reperfuse or routine angiography during inpatient stay.

The TRANSFER AMI [43] study published in 2009 randomized 1,059 patients with STEMI treated with fibrinolysis to standard treatment or immediate transfer and PCI (median 2.8 h). There was a significant reduction in the composite of death, reinfarction, recurrent ischemia, new or worsening congestive heart failure, or cardiogenic shock at 30 days (OR 0.64, p = 0.0004) in the group who were treated with fibrinolysis and transferred for PCI within 6 h with no significant difference in major bleeding between the two groups. In keeping with new evidence, pharmacoinvasive therapy in high-risk patients with low-bleeding risk has a class IIB recommendation in the 2009 ACC/AHA/SCAI focused update for STEMI [44].

Achieving timely PCI still presents a considerable challenge. The ongoing The Strategic Reperfusion Early After Myocardial Infarction (STREAM) study [45] is a prospective, randomized, parallel, comparative, international multicenter trial which is randomizing patients with STEMI to fibrinolysis combined with enoxaparin, clopidogrel, and aspirin, and cardiac catheterization within 6–24 h or rescue coronary intervention if reperfusion fails within 90 min of fibrinolysis versus PCI performed according to local guidelines. The outcome of this study which includes efficacy and safety end points should provide useful additional information to optimize therapeutic decisions. 1,500 of 2,000 patients have been randomized.

Rescue PCI

Failure of restoration of vessel patency after thrombolysis is not uncommon, manifesting as persistent ST elevation, and PCI in this situation is termed rescue PCI. Rescue PCI should be considered in this context up to 12 h after symptom onset. The REACT study was a multicenter randomized study in 427 patients which showed that rescue PCI was associated with a significantly higher event-free survival at 6 months when compared to repeat thrombolysis or conservative management [46]. A meta-analysis of randomized studies including REACT [47] also concludes that rescue PCI is associated with improved clinical outcomes.

Adjunctive Pharmacotherapy to PCI

Aspirin is recommended in the dose of 150–325 mg orally as part of dual antiplatelet agent strategy prior to PPCI. Clopidogrel is used in the dose of 300–600 mg for loading followed by 75 mg/day. A recent large Swedish observational study reports that upstream clopidogrel prior to arrival at the cath lab in patients undergoing PPCI was associated with a significant reduction in death/MI as well as death alone at 12 months follow-up. The dose of 300 mg for loading was found to be as effective as that of 600 mg in the Korean acute myocardial infarction registry [48]; however, other studies report that 600 mg loading dose is associated with better outcomes [49, 50]. The 2010 ESC guidelines on myocardial revascularization recommend 600 mg of clopidogrel as the loading dose [7].

Two new antiplatelet agents that have been approved recently are prasugrel and ticagrelor, and both have class I recommendation in the 2010 ESC guidelines for STEMI.

In the TRITON-TIMI 38 study [51], prasugrel, a thienopyridine that is more potent, more rapid in onset, and more consistent in inhibition of platelets than clopidogrel, was compared to clopidogrel in 13,608 patients with ACS scheduled for PCI. Prasugrel was associated with a significant reduction in the primary efficacy end point of cardiovascular death, nonfatal MI, and nonfatal stroke (hazard ratio 0.81). Prasugrel was also associated with a significant increase in major and life-threatening bleeding in certain high-risk subgroups. In the predefined STEMI group, 3,534 patients were randomized to receive either prasugrel (loading dose 60 mg, regular dose 10 mg/day) or clopidogrel (loading dose 300 mg, regular dose 75 mg)[52]. Treatment with prasugrel resulted in significant reductions in 30-day rates of cardiovascular death, nonfatal MI, or nonfatal stroke, a benefit that persisted out to 15 months with no difference in fatal or non-CABG-related bleeding.

Ticagrelor is an oral, reversible, direct-acting inhibitor of the adenosine diphosphate receptor P2Y12 that has a more rapid onset and more pronounced platelet inhibition than clopidogrel [53–55]. Of the 18,624 patients randomized to receive ticagrelor or clopidogrel in the PLATO study [53], 7,026 had STEMI. Ticagrelor (loading dose 180 mg, regular dose 90 mg BD) was associated with a significant reduction in the rate of death from vascular causes, myocardial infarction, or stroke without an increase in the rate of overall major bleeding but with an increase in the rate of non-procedure-related bleeding. The recommended duration of dual antiplatelet therapy after PPCI for STEMI is 12 months irrespective of the type of stent but should be tailored to individual patient.

The ACC/AHA/SCAI 2009 focused update for the management of ST-elevation myocardial infarction [44] advocates starting GPIIb/IIIa inhibitors during PPCI (class IIa) in selected patients and a class IIb recommendation for initiating GP GPIIb/IIIa inhibitors prior to PPCI. Following the HORIZONS AMI study [55], bivalirudin has class I recommendation for use in STEMI with or without prior treatment with unfractionated heparin and class IIa recommendation in patients with STEMI undergoing PCI who are at high risk of bleeding. The recent NICE guidance on the use of bivalirudin in STEMI concludes that there was sufficient evidence to demonstrate that bivalirudin was more clinically effective than glycoprotein IIb/IIIa inhibitor plus heparin, leading to lower rates of major bleeds and mortality [56] and cost dominant. Despite the improved clinical outcomes in HORIZIONS AMI for patients receiving bivalirudin, there was a statistically significant increase in the number of patients experiencing acute stent thrombosis (< 24 h) when compared to those in the unfractionated heparin arm. This difference disappeared after 24 h and did not affect overall clinical outcomes and a loading dose of 600 mg clopidogrel is recommended. Newer antiplatelets like prasugrel or ticagrelor could also potentially reduce the incidence of stent thrombosis and currently a trial comparing prasugrel plus bivalirudin with clopidogrel plus heparin is underway (BRAVE-4 NCT00976092).

Manual thrombus aspiration has class IIa recommendation in both AHA [44] and ESC [7

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree