GENERAL CONSIDERATIONS

In this chapter, the pelvis is considered to include the bony pelvis and its extraperitoneal soft tissues. Injuries involving the pelvis and its contents result in some of the most challenging and serious diagnostic problems to confront the radiologist, emergency physician, and traumatologist. Radiographically, this is particularly true for two reasons. First, the pelvis is the single area of the body that defies the radiologic dictum of obtaining radiographs in both frontal and lateral projections. Second, the soft tissue injuries frequently associated with pelvic skeletal injury are radiographically much less striking than the skeletal injury but are of far greater clinical significance.

The principal cause of death associated with pelvic trauma is hemorrhage, estimated to be as high as 60% in patients with major pelvic trauma.

1, 2 Interventional angiography has resulted in a significant reduction in this mortality rate.

3, 4Rupture of the bladder or urethral injury occurs in approximately 20% of patients with significant pelvic ring disruption (PRD). However, bladder and urethral injuries should be suspected in all patients with major pelvic trauma.

5, 6, 7The proper evaluation of urethral injuries requires a retrograde urethrogram (RUG) as the initial diagnostic procedure in all male patients with a PRD who are unable to void spontaneously.

8, 9, 10, 11, 12, 13, 14, 15 If the RUG is negative, a cystogram should be performed next. There is no justification for the insertion of a Foley catheter before performing an RUG in male patients with PRD. All male patients suspected of having a urethral injury, either on a clinical basis or because of radiographically demonstrated PRD, must have an RUG prior to insertion of a Foley catheter.

RADIOGRAPHIC ANATOMY

It is important to be familiar with changes in the radiographic appearance of the pelvis related to normal growth and development. This is so that (1) normal anatomy may not be misinterpreted as signs of trauma and (2) the basis of avulsive injuries of the adolescent pelvis may be understood and recognized.

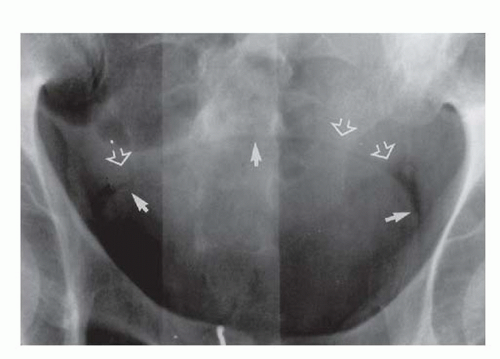

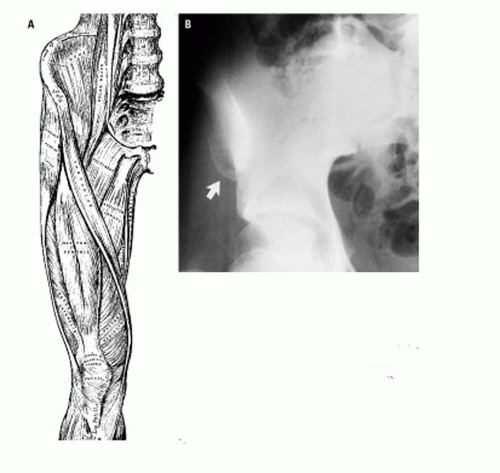

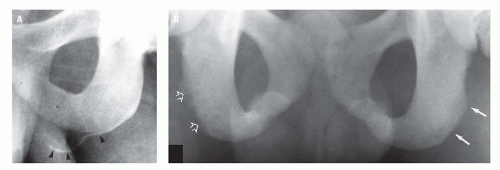

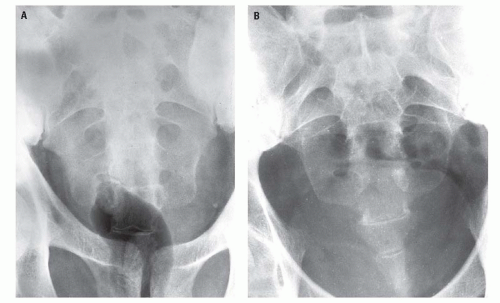

The radiographic appearance of the pelvis of a normal child is seen in

Figure 17.6. The triradiate cartilage (TRC), the site of union of the pubis, ischium, and ilium, usually fuses concomitant with puberty. The ischiopubic synchondrosis may fuse between the ages of 5 and 12 years.

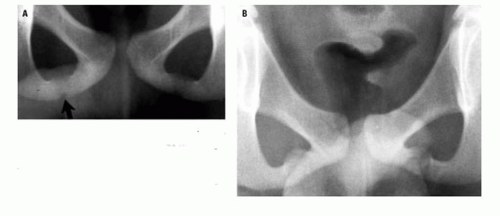

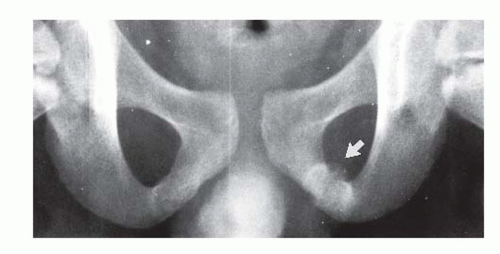

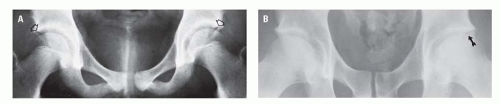

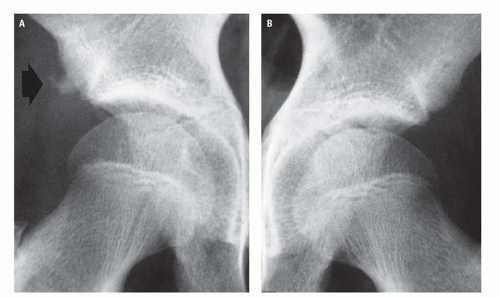

19 This synchondrosis varies greatly in radiographic appearance during the fusion process, not only from child to child (

Fig. 17.7) but also from side to side in the same child (

Fig. 17.8). The appearance of this synchondrosis rarely suggests an acute fracture but very commonly simulates a healing one (

Fig. 17.8). By age 14 years, the TRC is nearly fused and the ischiopubic synchondroses are fused (

Fig. 17.9).

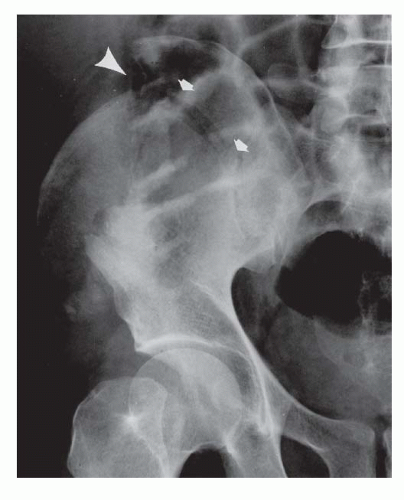

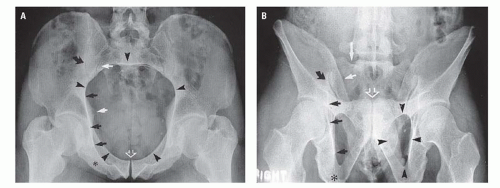

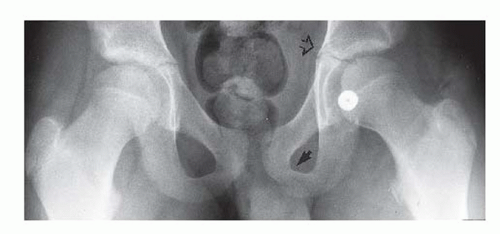

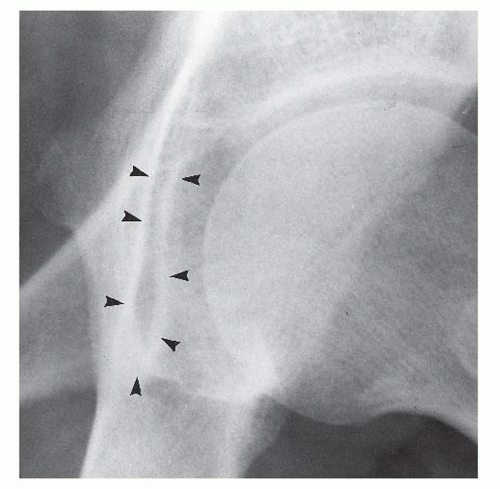

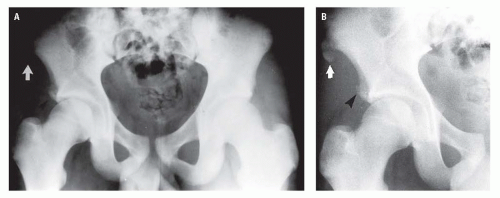

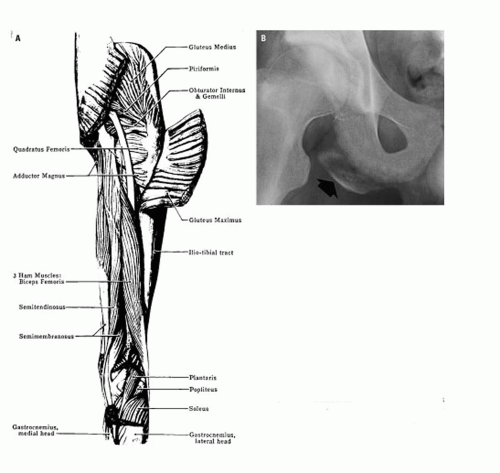

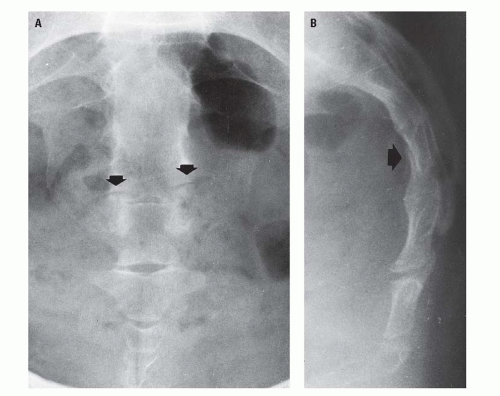

The pelvis of adolescents and young adults contains several apophyses that may be mistaken for acute fractures or that may be the site of acute avulsive injuries. These include apophyses of the iliac crest, the anterosuperior and inferior iliac spines, the ischial tuberosity (

Fig. 17.10), and the inferior margin of the pubic bodies (

Fig. 17.10B), all of which ossify with puberty and fuse between the ages 20 and 25 years.

20 The anterosuperior iliac spine apophysis is the site of origin of the sartorius muscle; the anteroinferior iliac spine apophysis, the rectus femur muscle; and the ischial apophysis, the hamstring muscles.

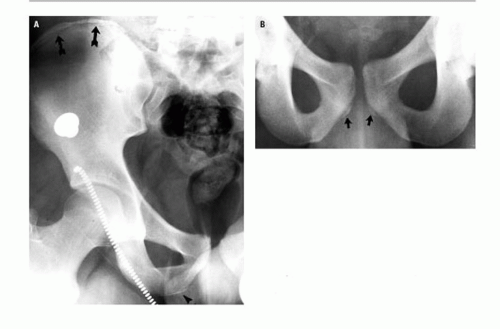

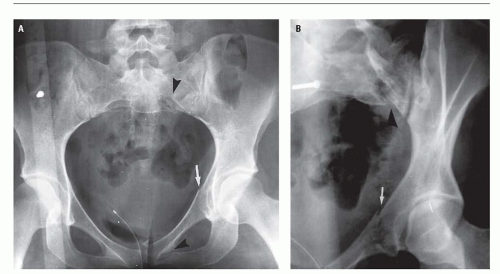

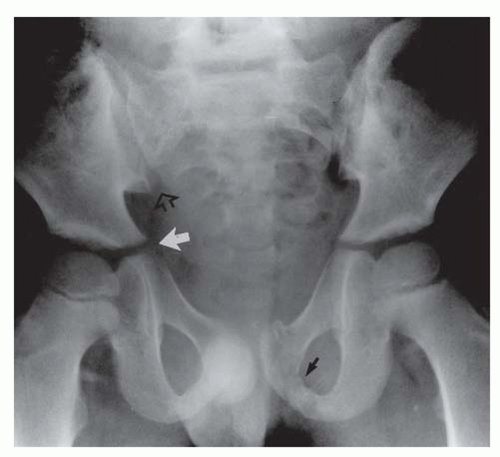

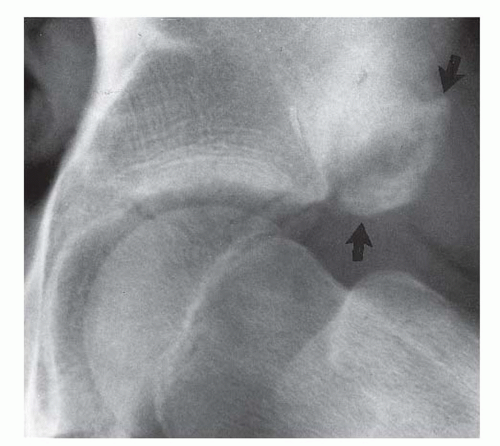

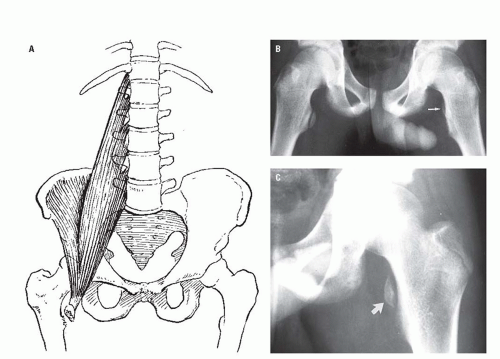

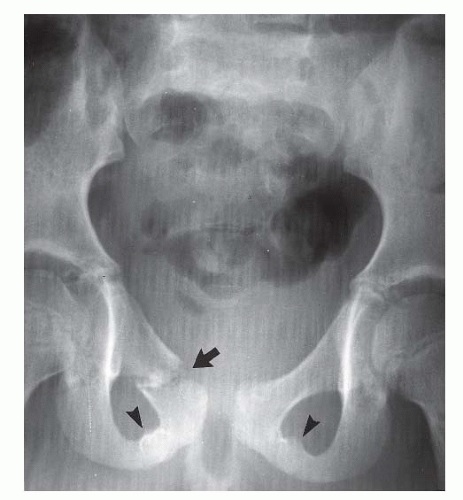

An inconsistent secondary ossification center may constitute the superior aspect of the posterior acetabular lip either unilaterally or bilaterally. These centers, which usually appear between the ages of 14 and 18 years and fuse in early adulthood, may persist ununited throughout adult life as the os acetabuli and simulate a posterior acetabular lip fracture (

Fig. 17.11). As with ununited secondary ossification centers elsewhere, dense cortication of the margins of the separate center and smooth sclerotic contiguous surfaces of the adjacent portions of the pelvis and ununited center (

Fig. 17.11) should easily distinguish these ununited secondary ossification centers from an acute fracture fragment.

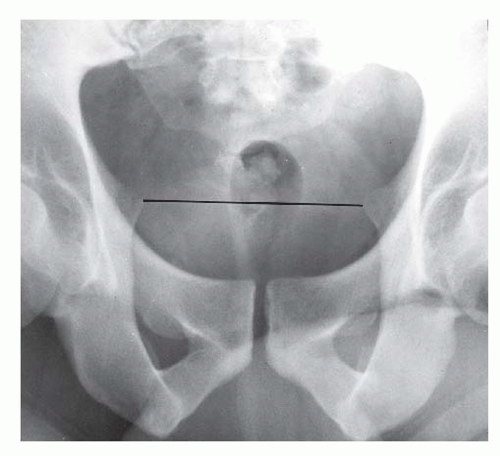

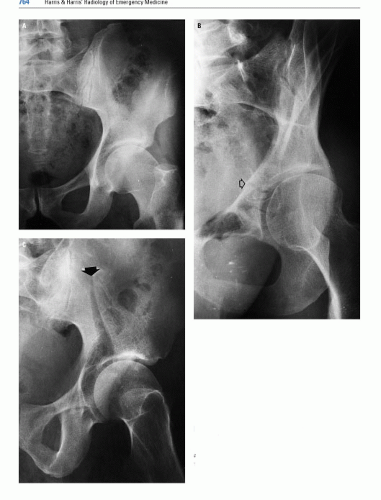

In the straight AP radiograph of the adult, the pelvic ring is the round or oval plane of the inlet of the true pelvis and includes the sacral promontory, the inferior margins of the SI joints, the iliopectineal line extending to the superior margin of the superior pubic rami, and the superior margin of the pubic symphysis. The pelvic ring is divided into an anterior and a posterior arch by an imaginary line connecting the ischial spines (

Fig. 17.12). The ilioischial line (

Figs. 17.1 and

17.3) is not a single bony margin but is composed, superiorly, of the arc of the quadrilateral plate tangent to the x-ray beam and, inferiorly, by the internal cortex of the ischium extending to its tuberosity. The ilioischial line extends obliquely downward lateral to the iliopectineal line. The quadrilateral plate comprises the lateral surface of the true pelvis (birth canal) and, as such, constitutes the medial wall of the acetabulum.

The teardrop shadow of the pelvis (

Fig. 17.13) is a composite U-shaped shadow located at the anteroinferior portion of the acetabular fossa and constitutes the anterior margin of the acetabular notch. It consists of cortical and medullary bone principally of the ischium with a small medial component from the superior pubic ramus.

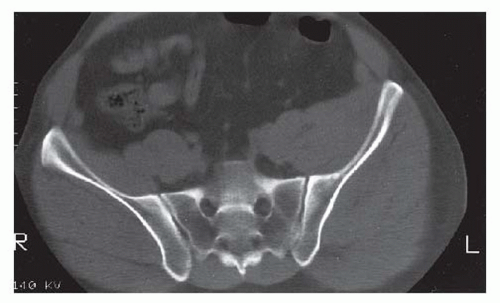

21The SI joints are oblique structures with the sacral alar component anterior to the iliac wing component. Consequently, the iliac and sacral alar margin of the anterior edge of the SI joint is usually clearly recognizable throughout its vertical extent. The posterior margin of the SI joint, which lies medial to the anterior margin, is much less well seen on the AP radiograph of the pelvis and is frequently identified only by the posterior margin of the iliac wing component (

Fig. 17.3). Oblique views intended to demonstrate the SI joints en face usually only demonstrate the anterior aspect of the joint space. The SI joints are optimally demonstrated on axial CT images (

Fig. 17.14). An important anatomic relationship is formed by the inferior cortical margins of the contiguous sacral alar and iliac surfaces of the anterior margins of the SI joints, which normally should be on the same plane or constitute a continuous imaginary arc (

Fig. 17.1).

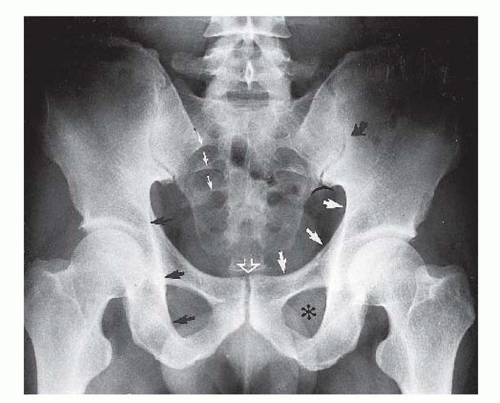

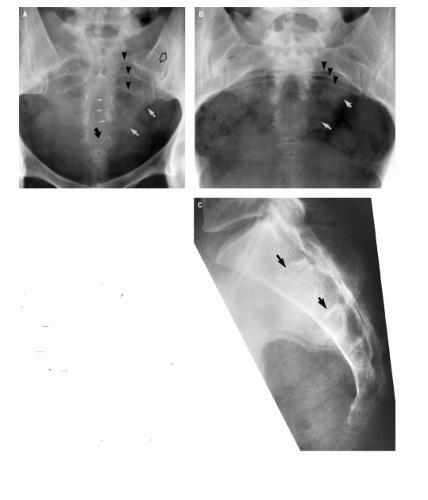

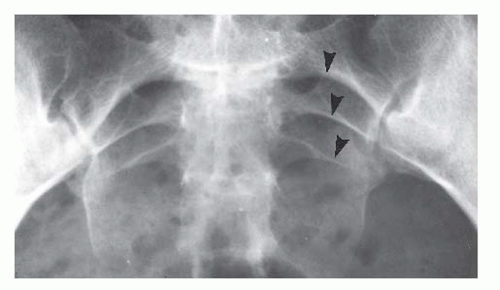

The sacral arcuate lines (

Fig. 17.15), sometimes incorrectly referred to as “struts,” reflect the normal anatomy of the sacral foramina. The arcuate lines do not represent a specific cortical edge. Rather, they represent the arc of the superior surface of the sacral foramen that happens to be tangent to the x-ray beam. As described by Jackson et al., the sacral arcuate lines appear as rather sharply defined, superiorly convex curvilinear densities that are broad superomedially and taper gently and smoothly as they extend inferolaterally.

22 The arcuate lines are normally equidistant from each other and are bilaterally symmetrical. Usually, the arcuate lines of only the upper three foramina are visible on the straight AP radiograph of the pelvis.