There are a number of points to be considered when looking at a plain abdominal film:

- Analyze the intestinal gas pattern and identify any dilated portion of the gastrointestinal tract.

- Look for gas outside the lumen of the bowel.

- Look for ascites and soft tissue masses in the abdomen and pelvis.

- If there are any calcifications, try to locate exactly where they lie.

- Assess the size of the liver and spleen.

Intestinal Gas Pattern

Relatively large amounts of gas are usually present in the stomach and colon in a normal patient. The stomach can be readily identified by its location above the transverse colon, by the band-like shadows of the gastric rugae in the supine view. The duodenum often contains air and there may be some gas in the normal small bowel, but it is rarely sufficient to outline the whole of a loop. If the bowel is dilated it is important to try and decide which portion is involved.

Dilatation of the Bowel

The initial diagnosis of intestinal obstruction is usually made on clinical examination with the help of plain abdominal films. Dilatation of the bowel is the cardinal plain film sign of intestinal obstruction, and the pattern of dilatation is the key to the radiological distinction between small and large bowel obstruction. In small bowel obstruction, the small intestine is dilated down to the point of obstruction and the bowel beyond this point is either empty or of reduced calibre. In large bowel obstruction, the large bowel is dilated down to the level of obstruction. If the ileocaecal valve, where the ileum joins the colon, is incompetent, there will also be small bowel dilatation. Making the distinction between large and small bowel obstruction depends on the ability to recognize which portions of bowel are dilated.

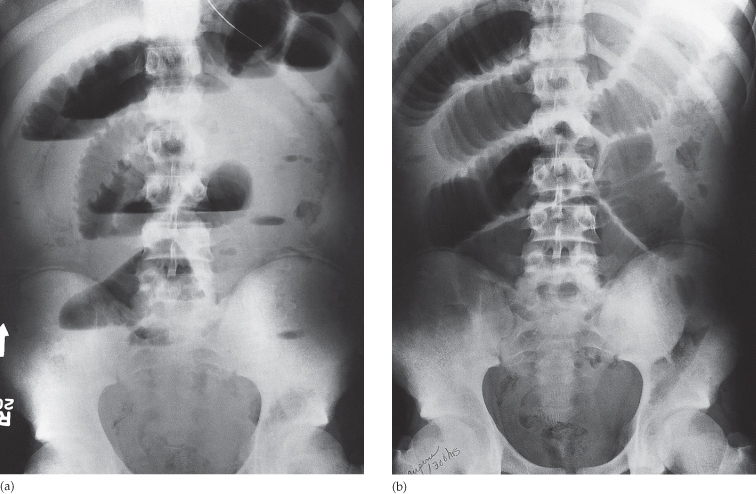

Dilated small bowel usually lies in the centre of the abdomen within the ‘frame’ of the large bowel (but the sigmoid and transverse colon may be redundant and may also lie in the centre of the abdomen, particularly when dilated). When the proximal and mid small intestine are dilated, the valvulae conniventes (plica circulares) can be identified. The valvulae conniventes are always closer together and cross the width of the bowel (the colonic haustra do not), often giving rise to an appearance known as a ‘stack of coins’ (Fig. 5.2). The distal small intestine has a relatively smooth outline and it may be difficult to distinguish the lower ileum and the sigmoid colon because both may be smooth in outline. The radius of curvature of the loops is sometimes helpful: the tighter the curve, the more likely the loop is to be dilated small bowel.

Fig. 5.2 Small bowel obstruction due to adhesions. (a) The jejunal loops are markedly dilated and show air–fluid levels in the erect film. The jejunum is recognized by the presence of valvulae conniventes. (b) The ‘stack of coins’ appearance is well demonstrated in the supine film. Note the large bowel contains less gas than normal.

The colon is recognized by its haustra, which usually form incomplete bands across the colonic gas shadows. Haustra are always present in the ascending and transverse colon, but may be absent distal to the splenic flexure. The presence of solid faeces is a useful and reliable indication of the position of the colon. The number of dilated loops is another valuable distinguishing feature between small and large bowel dilatation, because even with a very redundant colon the numerous layered loops that are so often seen with small bowel dilatation are not present.

If the cause or site of the obstruction is not evident from plain films, and immediate exploratory surgery is not indicated, then computed tomography (CT) or a contrast study (either a follow-through for small bowel obstruction or instant enema for large bowel obstruction) is helpful. CT can demonstrate the site of obstruction by showing the location of the transition from dilated to collapsed bowel, and can confirm or exclude a mass at the site of obstruction (Fig. 5.3). With the increasing availability of CT, contrast follow-throughs are performed less frequently.

Fig. 5.3 Large bowel obstruction due to carcinoma at the splenic flexure. There is marked dilatation of the large bowel from the caecum to the splenic flexure.

Dilatation of the bowel occurs in a number of conditions. In remembering causes of mechanical bowel obstruction it is often easiest to think of conditions that: (i) obstruct the lumen (e.g. gall stone ileus); (ii) affect the bowel wall and cause a narrowing (e.g. Crohn’s disesase; or (iii) cause extrinsic compression of the bowel (e.g. adhesions). Bowel dilatation, however, occurs in conditions other than mechanical bowel obstruction, notably: paralytic ileus, acute ischaemia and inflammatory bowel disease. The radiological diagnosis of these phenomena depends mainly on the pattern of distribution of the dilated loops (Table 5.1).

Table 5.1 Patterns of bowel dilatation in gastrointestinal conditions

| Diagnosis | Pattern of bowel dilatation |

| Mechanical obstruction of the small bowel (Fig. 5.2) | Small bowel dilatation, but colon is normal or reduced in calibre. Computed tomography may also show any responsible tumour or inflammatory mass |

| Mechanical obstruction of the large bowel (Fig. 5.3) | Dilatation of the colon down to the point of obstruction. May be accompanied by small bowel dilatation if the ileocaecal valve becomes incompetent |

| Generalized paralytic ileus (Fig. 5.4) | Both the large and the small bowel are dilated. The dilatation often extends down into the sigmoid colon and gas may be present in the rectum. It may be difficult to differentiate from low large bowel obstruction |

| Localized peritonitis | Often causes dilatation of the bowel loops adjacent to the inflammatory process (which may be specifically visible on computed tomography), giving rise to the so-called sentinel loops seen, for example, in appendicitis and pancreatitis |

| Gastroenteritis | Variable pattern. Some patients have a normal film and some show excess fluid levels without dilatation, whereas some mimic paralytic ileus and others mimic small bowel obstruction |

| Small bowel infarction | May mimic obstruction of the small bowel or obstruction of the large bowel depending on the distribution of the ischaemia |

| Closed loop obstruction (Fig. 5.5) | The diagnosis depends on whether the loop in question contains air. If it does, as for example in a caecal or sigmoid volvulus, the dilated loop is seen filled with gas in a characteristic shape. If the closed loop is filled with fluid – the common situation in most obstructed hernias – it may not be visible |

| Toxic dilatation of the colon (Fig. 5.6) |