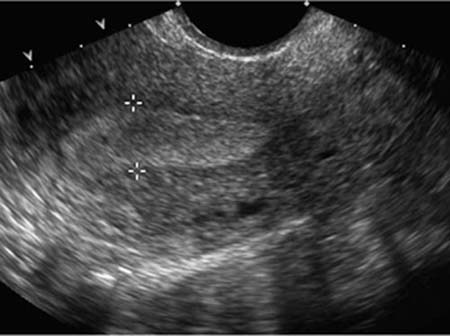

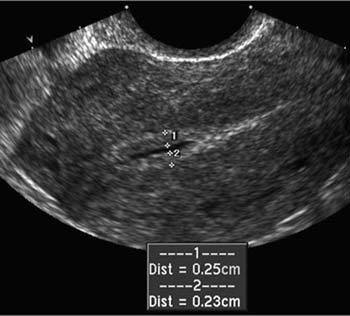

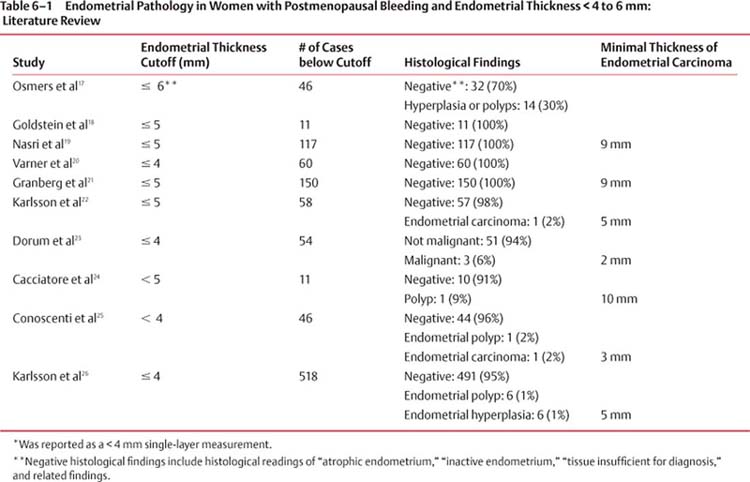

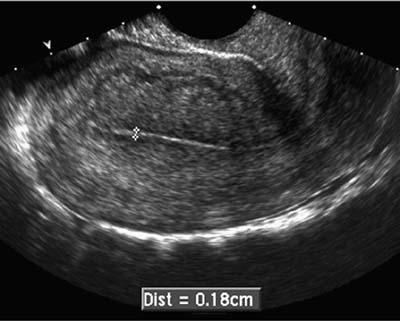

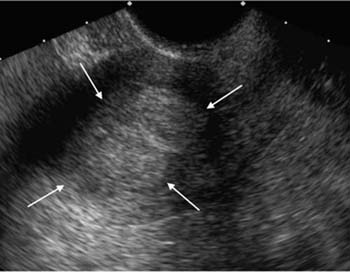

6 Postmenopausal Vaginal Bleeding Postmenopausal vaginal bleeding is an important, and fairly common, problem in older women. It can be the presenting symptom of endometrial cancer, the fourth most common malignancy in women in the United States,1 and the most common pelvic gynecologic malignancy.2 Because of this, “unscheduled” postmenopausal bleeding (i.e., any bleeding other than that occurring at the expected time in the cycle of a woman on sequential hormone replacement therapy3) merits diagnostic evaluation. Henceforth, the term postmenopausal bleeding will refer to unscheduled bleeding. Conventional teaching, until recently, has been that any woman with postmenopausal bleeding should undergo endometrial sampling (via one of the methods that will be described here).2,3 With the advent of transvaginal sonography, done on its own or following the instillation of saline into the uterine cavity, the endometrium can be examined in exquisite detail in a minimally invasive fashion. This permits a more selective and directed approach to biopsying the endometrium in women with postmenopausal bleeding. There are several etiologies of postmenopausal bleeding. The most common cause is endometrial atrophy.4,5 The endometrium in a postmenopausal woman typically becomes thin and atrophic. This atrophic endometrium is prone to develop superficial ulcers that bleed. Bleeding can also be caused by several endometrial lesions, including endometrial carcinoma, which accounts for ~7 to 30% of cases of postmenopausal bleeding,4–6 endometrial hyperplasia, and endometrial polyps. These lesions are somewhat interrelated, in that polyps may contain foci of malignancy or hyperplasia, and endometrial hyper-plasia (especially in the presence of cytological atypia) may progress to carcinoma. In one series, 23% of women with atypical hyperplasia subsequently developed endometrial carcinoma, as did 1.6% of women with simple hyperplasia.7 In addition to endometrial lesions, submucosal fibroids can be a cause of postmenopausal bleeding. There are several ways to obtain an endometrial tissue specimen for pathological evaluation. Endometrial tissue can be obtained by dilation and curettage (D&C), usually performed in an operating room, or via an “office biopsy.” The latter is substantially lower in cost and morbidity.8,9 Both of these procedures obtain tissue from only a portion of the endometrium and so may miss lesions due to sampling error. In a study of 50 patients who had D&C immediately preceding hysterectomy, examination of the hysterectomy specimen revealed that in 16% of patients less than a quarter of the cavity had been sampled, and in 60% of patients less than half the endometrium had been sampled.10 Office biopsies are likely to obtain even more limited samples. Both D&C and office biopsy have been shown to have sensitivities below 100% for endometrial pathology, with polypoid lesions being missed most frequently. The false-negative rate of D&C is often found to be in the range of 2 to 6%, with somewhat higher rates for office biopsy.11 Some studies have found even higher false-negative rates. Grimes estimated office biopsy to have a sensitivity of 96% for endometrial cancer and 80% for endometrial hyperplasia.8 In 407 patients undergoing D&C prior to hysterectomy, Stovall et al found that D&C correctly diagnosed 28 of 30 cancers (93%) and 28 of 51 cases of hyperplasia (55%).12 Although the reported sensitivity of office biopsy and D&C varies from study to study, it is clear that both of these sampling procedures miss some cases of endometrial pathology. Another method of obtaining endometrial tissue for pathological examination is hysteroscopically guided biopsy. Because the biopsy is not performed blindly, but instead can be directed to sites of grossly visible abnormalities, this approach is less prone to sampling error. In particular, focal lesions such as polyps, or a small patch of malignant tissue, are less likely to be missed by hysteroscopically guided biopsy than by blind biopsy techniques (office biopsy or D&C). However, the cost of this procedure, and the skill required to carry it out expertly, limits its applicability to selected cases. Furthermore, some hystero-scopes do not have an operating channel through which biopsy can be performed, which necessitates removing the scope prior to biopsy. Figure 6–1 Endometrial thickness measurement technique. The measurement is done on a sagittal transvaginal image, measuring from the anterior endometrial–myometrial interface to the posterior endometrial–myometrial interface (calipers). This is a double-layer measurement because it includes both the anterior and the posterior layers of endometrium. Hysterosalpingography and magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) can provide diagnostic information about the endometrium. The former can play a useful role in the workup of infertility,13 but does not contribute to the evaluation of postmenopausal bleeding. Magnetic resonance imaging can occasionally be used for this purpose in patients with inadequate sonogram and sonohysterogram and who cannot undergo endometrial sampling due to cervical stenosis.14 Its main role in endometrial evaluation, however, lies not in the workup of postmenopausal bleeding, but in the preoperative staging in cases of proven endometrial carcinoma.15,16 The literature on ultrasound of the postmenopausal uterus is extensive and has focused on several questions. Is there an endometrial thickness below which significant endometrial pathology can be confidently excluded? How is endometrial thickness affected by various regimens of hormone replacement therapy? Besides endometrial thickness, can other sonographic features (e.g., echotexture of the endometrium, Doppler waveforms) identify pathology and distinguish among various pathological conditions? Can sonohysterography aid in the differential diagnosis of postmenopausal bleeding? Figure 6–2 Endometrial thickness measurement with fluid in the endometrial cavity. The anterior endometrium (calipers #1) and posterior endometrium (calipers #2) are measured, and the values of 0.25 cm and 0.23 cm are summed to yield the endometrial thickness measurement of 0.48 cm (4.8 mm). Postmenopausal endometrial thickness and its relationship to endometrial pathology have been extensively studied.17–26 Although the technique for measuring endometrial thickness varies somewhat among different authors, most use double-layer endometrial measurements (anterior and posterior layers) obtained via transvaginal sonography. The endometrium is imaged sagittally and is measured at its thickest point from the anterior to the posterior endometrial–myometrial junction (Fig. 6–1). Each of these junctions is generally easy to identify because the endometrium is typically hyperechoic and the inner myometrium hypoechoic. If there is fluid in the endometrial cavity, the anterior and posterior layers of the endometrium are measured separately and the two values are summed (Fig. 6–2). Table 6–1 summarizes the results of several studies examining whether there is a thickness cutoff below which significant endometrial pathology can be excluded in women with postmenopausal bleeding. In each study, patients underwent sonography shortly before endometrial tissue sampling, usually by D&C or hysterectomy. Most of the studies employ a cutoff of 4 or 5 mm. Although the findings vary somewhat among studies, the overall pattern of results suggests that postmenopausal bleeding is rarely due to significant endometrial pathology (carcinoma, hyperplasia, or polyp), and almost never due to carcinoma, when the endometrial thickness is ≤ 4 to 5 mm. Using a conservative cutoff of ≤ 4 mm (Fig. 6–3), postmenopausal bleeding can be attributed to endometrial atrophy with a high degree of confidence when the endometrial thickness is below this cutoff.27,28 Figure 6–3 Thin endometrium. The endometrial thickness (calipers) is 0.18 cm (1.8 mm). It should be noted that, although a thickness below 4 to 5 mm largely excludes significant pathology, a greater measurement does not exclude endometrial atrophy. In the 1995 Karlsson study, for example, among 245 women with endometrial thicknesses of 6 to 10 mm, 88 (36%) had endometrial atrophy.26 In a small fraction of cases the endometrial margins are obscure, so that the thickness cannot be measured. This is most likely to occur when there are uterine fibroids distorting the endometrium. In these cases, the sonogram provides no information about the presence or nature of endometrial pathology.18 Most studies have found that the endometrial thickness in cases of endometrial carcinoma is larger, on average, than it is with polyps or hyperplasia.17,19,21,22,24–26 In the largest study, for example, the mean thickness with endometrial cancer was 21.1 mm, compared with 12.9 mm for polyps and 12.0 mm for hyperplasia.26 However, there is considerable overlap in endometrial thickness among these three lesions, so that the degree of thickening cannot be used to make a specific diagnosis. Endometrial thickness in postmenopausal women is somewhat affected by hormone replacement therapy, which some women take to counter the effects of menopause. Several treatment regimes are available, employing estrogen with or without progesterone. Estrogen suppresses hot flashes and reduces the risk of osteoporosis and cardiovascular disease in postmenopausal women. It has the drawback of increasing the likelihood of endometrial hyperplasia or carcinoma and so is often given in combination with progesterone, which decreases the risk of endometrial pathology. Progesterone, when used, can be given either continuously or periodically (e.g., the first 10 to 14 days of each month), leading to three types of treatment regimen: estrogen only, continuous estrogen/progesterone, and sequential estrogen/progesterone. On the last of these regimens, “withdrawal” bleeding is expected each month and is not associated with endometrial pathology, so that bleeding in women on sequential therapy merits diagnostic workup only when unscheduled.3,29 Figure 6–4

Differential Diagnosis

Diagnostic Evaluation

Nonimaging Tests

Imaging Tests Other than Ultrasound

Ultrasound Imaging

![]()

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree