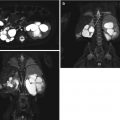

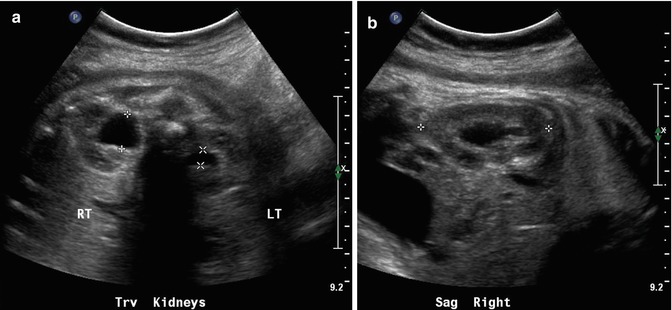

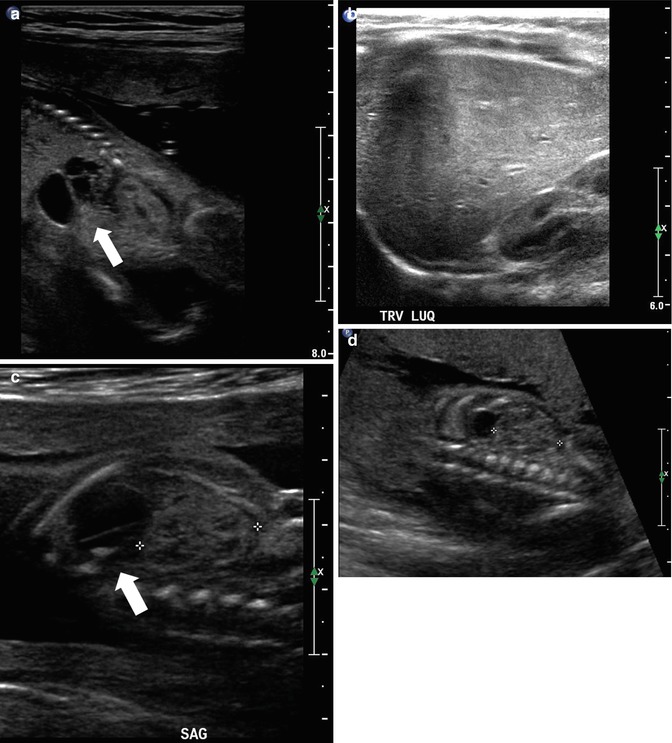

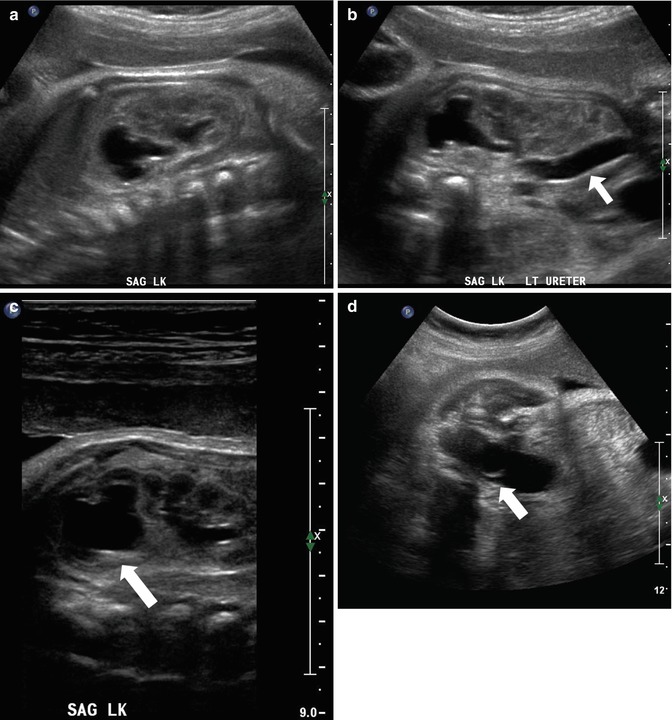

Fig. 8.1

This fetal sonogram reveals mild, bilateral hydronephrosis, in the sagittal (a) and transverse planes (b), measuring 5 mm in anterior-to-posterior dimensions, at 29 weeks gestation, with a normal, full fetal urinary bladder (c). After delivery, the appearance of the kidneys normalized, as is often the case. By 1 month of age, with a full urinary bladder (d), an 8 MHz curved probe reveals a normal appearance of the right kidney in the sagittal plane (e). Detail is even more apparent using a 12 MHz linear probe in the sagittal (f) and transverse (g) planes, with normal corticomedullary differentiation and no hydronephrosis

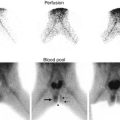

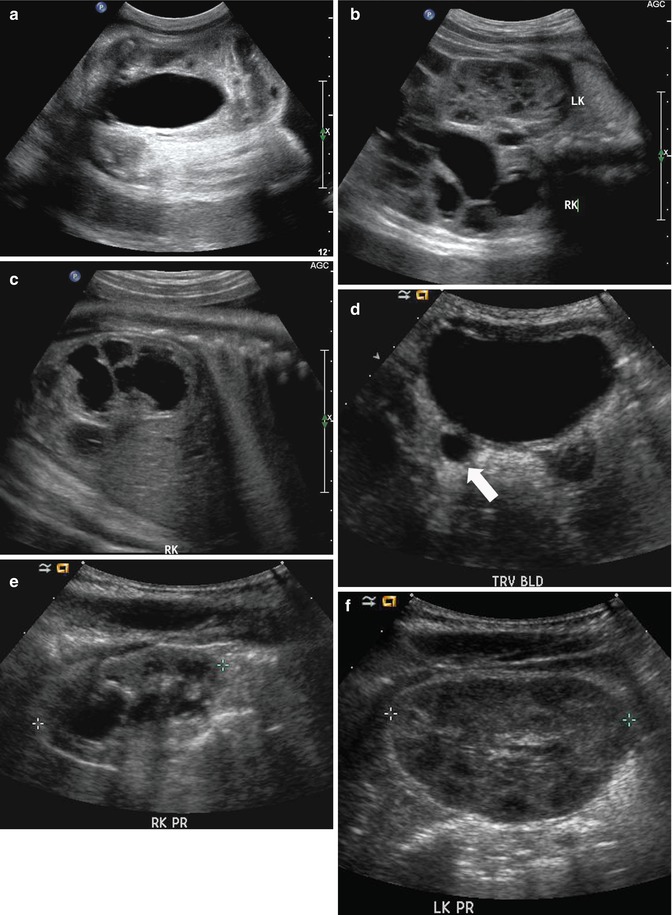

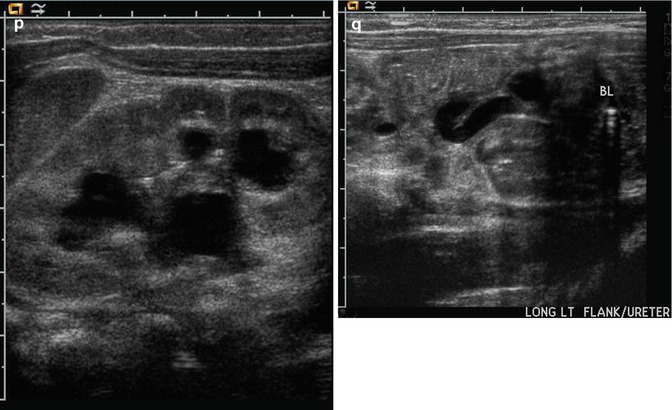

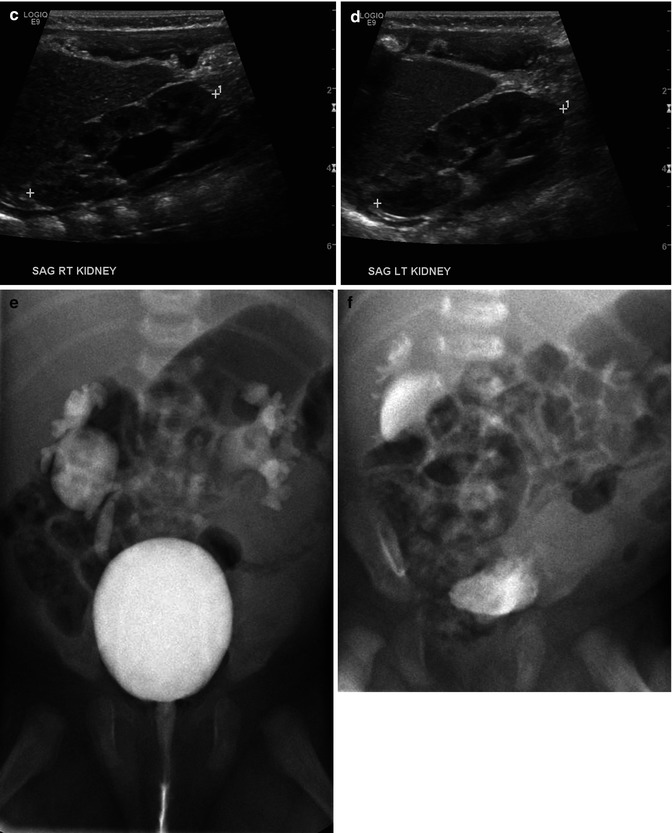

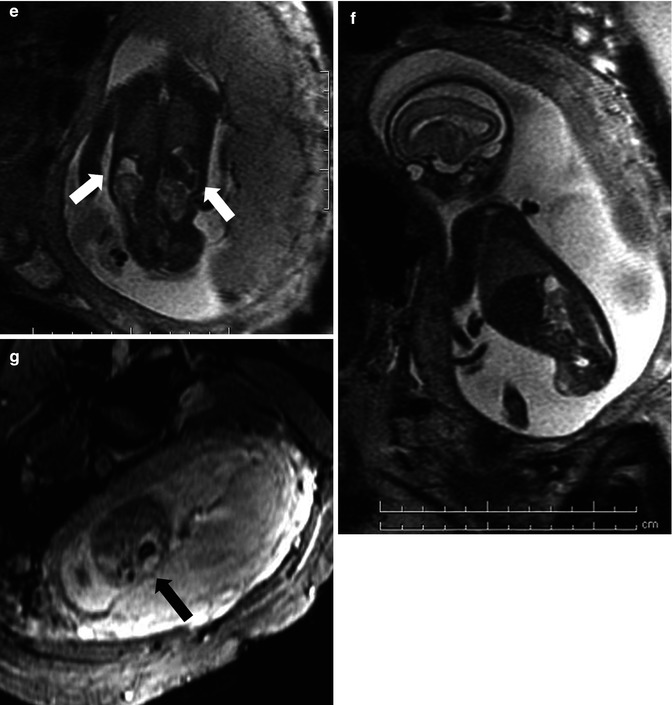

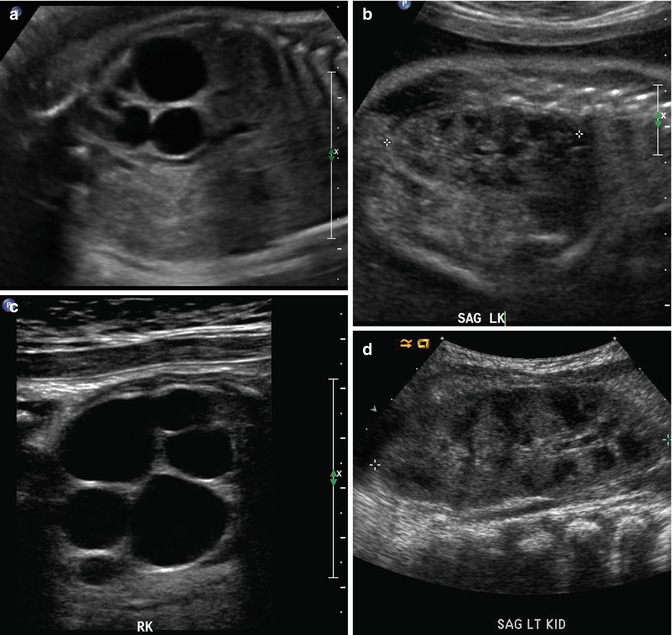

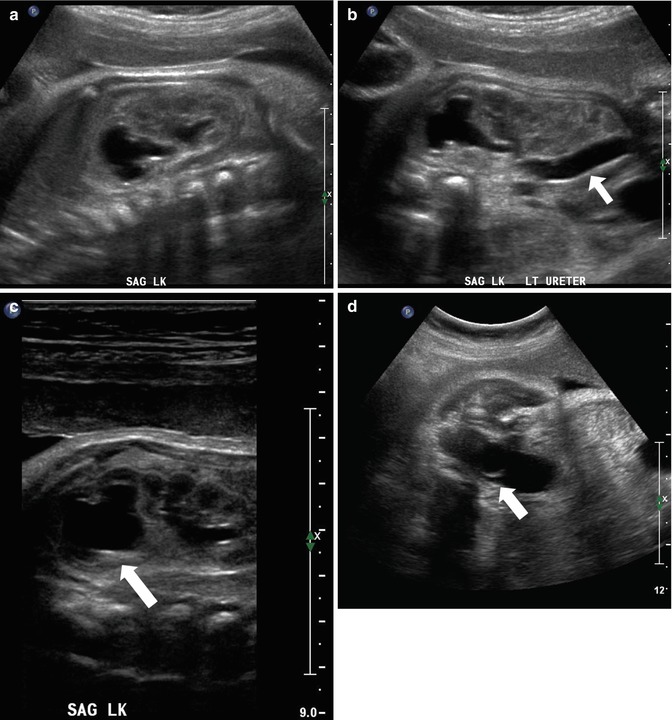

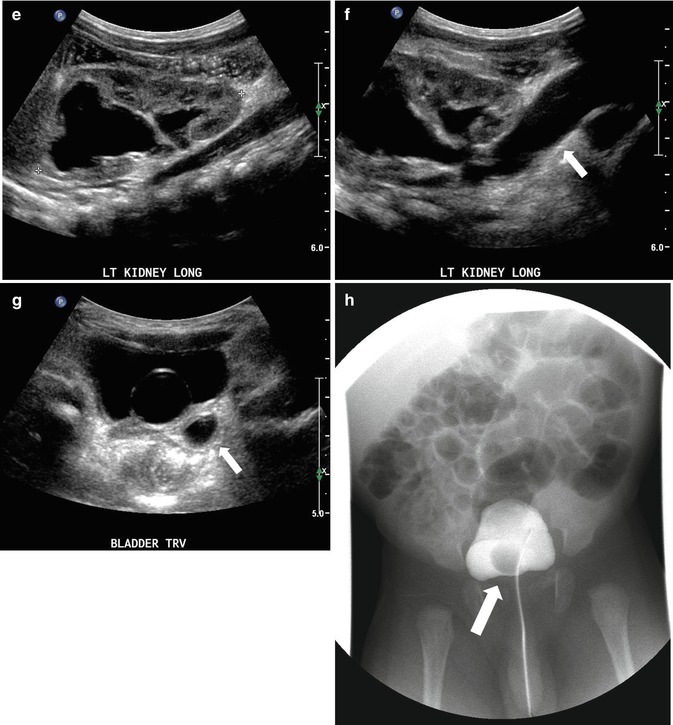

Fig. 8.2

This sonogram of a 33-week male fetus demonstrates a rather full but not thick-walled bladder (a) and moderate to severe right hydroureteronephrosis (b and c). Sonography at 4 weeks old confirms the presence of moderate to severe right hydroureteronephrosis (d and e, arrow = right distal ureter), some evidence for right-sided renal cortical loss (e), and a normal-appearing left kidney (f). VCUG on the same day proves that the dilatation is due to high-grade, right-sided reflux (g) that drains well (h), with no evidence for posterior urethra valves on voiding (i). Renal scintigraphy was performed at age 3 months, and this posterior view reveals evidence for diffuse cortical loss on the right (j)

Ultrasound features that might be associated with some type of uropathology include pelvic AP diameter greater than 8 mm, massive dilation of the ureters and renal pelvis bilaterally, increased renal cortical echogenicity, thickened bladder wall, and reduced levels of amniotic fluid. Lee et al. in 2003 showed in a meta-analysis that moderate to severe hydronephrosis had a higher risk of pathology [23]. However, no other specific ultrasound features were found to have any predictive value [22, 24]. The differential diagnosis of fetal hydronephrosis is lengthy and includes obstructive processes such as ureteropelvic or ureterovesical obstruction as well as posterior urethral valves in boys, reflux of urine from the bladder to the renal collecting system, and more uncommon conditions such as prune-belly syndrome. Again, it is important to remember that dilatation of the upper urinary tract is not necessarily due to obstruction and that ultrasound alone is not an accurate test for obstruction as it does assess function or physiology.

The etiology of idiopathic hydronephrosis has not been determined, but the suspicion is that the ureter may have been kinked early in development as urine production starts. The kinking causes a transient obstruction to the flow of urine which will then cause back up of urine into the renal collecting system, thus, causing dilation. With differential growth of the fetus, the ureter may straighten out and the obstructive process may disappear leaving the collecting system dilated to varying degrees.

Marked dilation of the renal collecting system may be associated with high-grade obstruction (Fig. 8.3). If it is bilateral, the obstructive process may be intravesical (posterior urethral valves in males) (Fig. 8.4). As noted above, the more severe the degree of dilation of the renal collecting system, the more likely the chances of pathology [23, 25]. Vesicoureteral reflux has been mentioned as a possible etiologic factor for prenatally diagnosed hydronephrosis and is reported to be present in approximately 12 % of fetuses with ANH independent of the grade of hydronephrosis [23]. The diagnosis of reflux cannot be achieved by prenatal ultrasound but requires postnatal evaluation by VCUG (Fig. 8.5). Suspicion of vesicoureteral reflux can be raised if, while monitoring the bladder and kidneys, upper tract dilation is seen at the time of bladder contraction. This is a rather subtle and unreliable finding but has been described as a possible feature of prenatal vesicoureteral reflux [26]. Concomitant presence of both an obstructive process, as well as reflux, may also be present (Fig. 8.5).

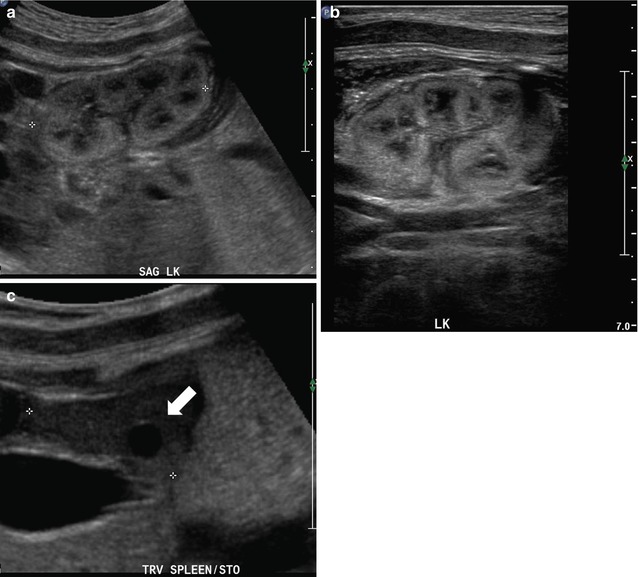

Fig. 8.3

At 21 weeks gestation, fetal sonography reveals moderate to severe left hydronephrosis, without hydroureter, and a normal-appearing right kidney (a). At age 4 weeks, postnatal renal sonography confirms this suspicion, and the degree of left hydronephrosis is even worse, with very little visible cortex, with a still normal-appearing right kidney (b and c). Diuretic nuclear renography (not shown) demonstrates a clearly obstructive pattern of excretion, indicating that the fetal hydronephrosis was due to isolated ureteropelvic junction obstruction

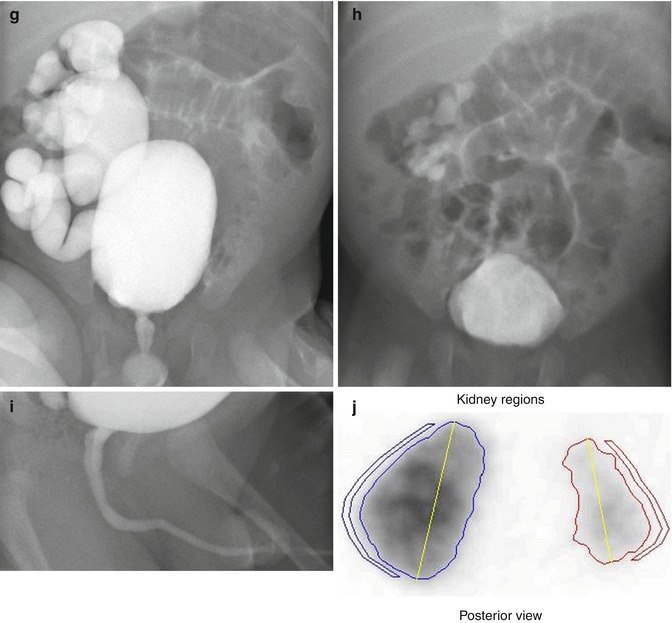

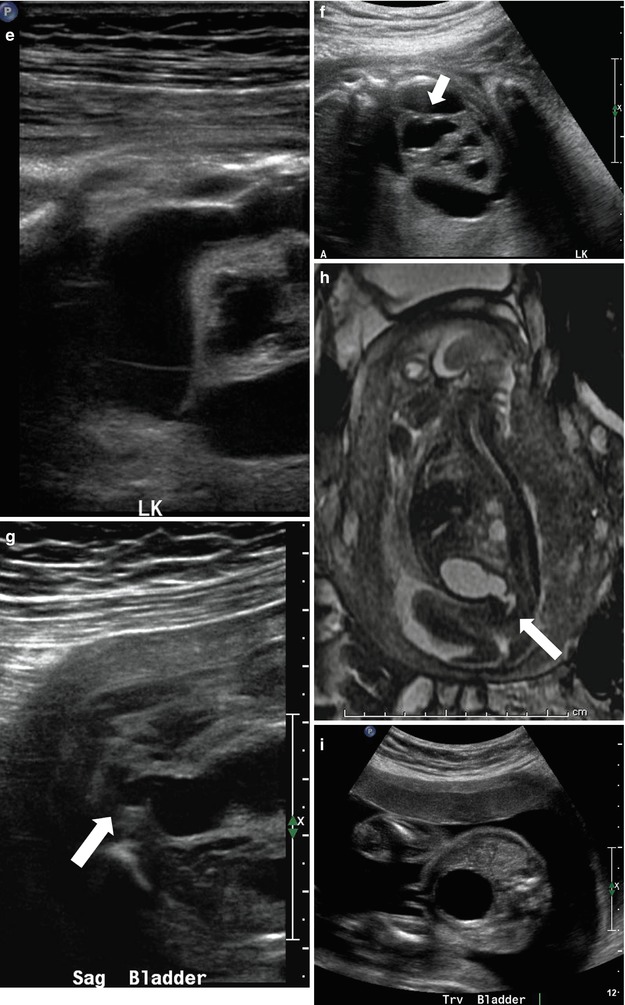

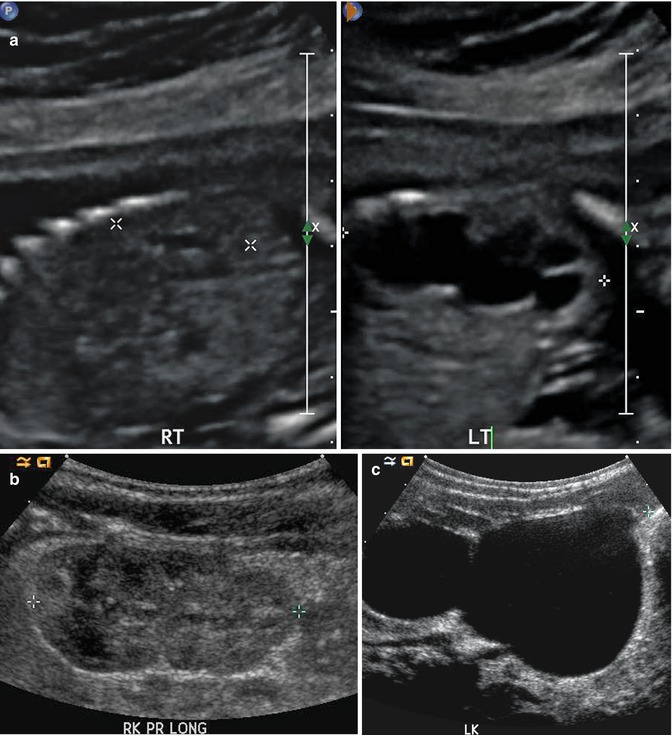

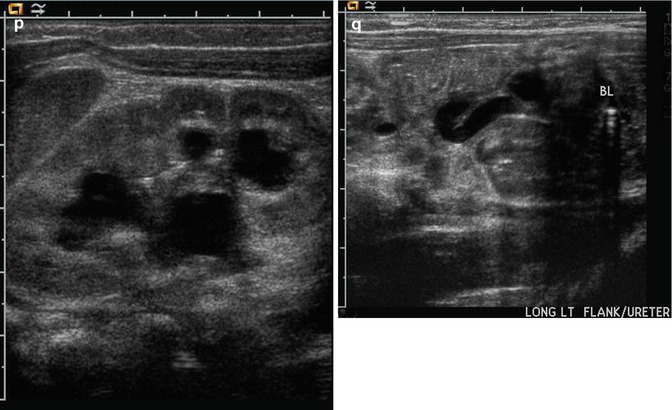

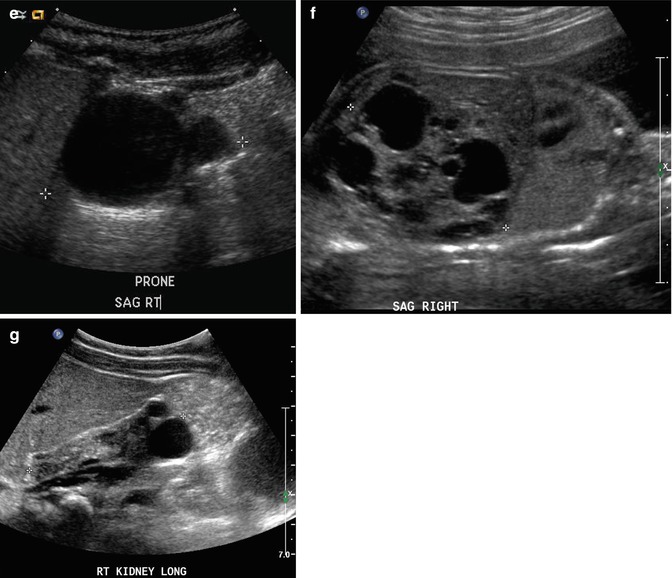

Fig. 8.4

This figure demonstrates four different examples of fetuses with posterior urethral valves. The first presents at 20 weeks gestation with anhydramnios, bilateral hydronephrosis (a), a dilated, thick-walled urinary bladder (b, arrow), and dilated posterior urethra (c, arrow). The second example is one of the diamniotic-dichorionic twins (d, e, and f), presenting at 26 weeks gestation, with bilateral hydronephrosis, perinephric urinomas (d, arrow, e), and compression of the abnormally echogenic renal cortex by the urinoma (f, arrow). The third example is revealed by both sonography (g) and MRI (h), with oligohydramnios, a dilated urinary bladder, and dilated posterior urethra (arrow). Finally, the fourth example presents at 24 weeks with a dilated, thick-walled urinary bladder (i and j), asymmetric hydronephrosis (k), and a dilated posterior urethra by sonography (l, arrow). After delivery, a voiding cystourethrogram proves the presence of posterior urethra valves (m, arrow) and high-grade, right-sided vesicoureteric reflux, with multiple bladder diverticula (n). Postnatal sonography reveals diffuse, right-sided renal cortical thinning, but no hydronephrosis (o), while the left renal cortex is normal, but there is both hydronephrosis (p and q) and hydroureter. All but the fourth example died shortly after delivery as a result of pulmonary hypoplasia

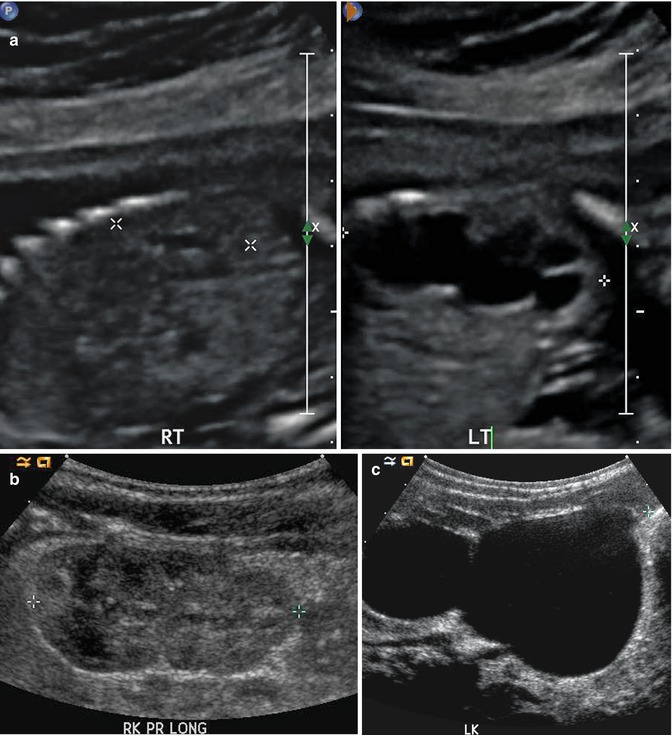

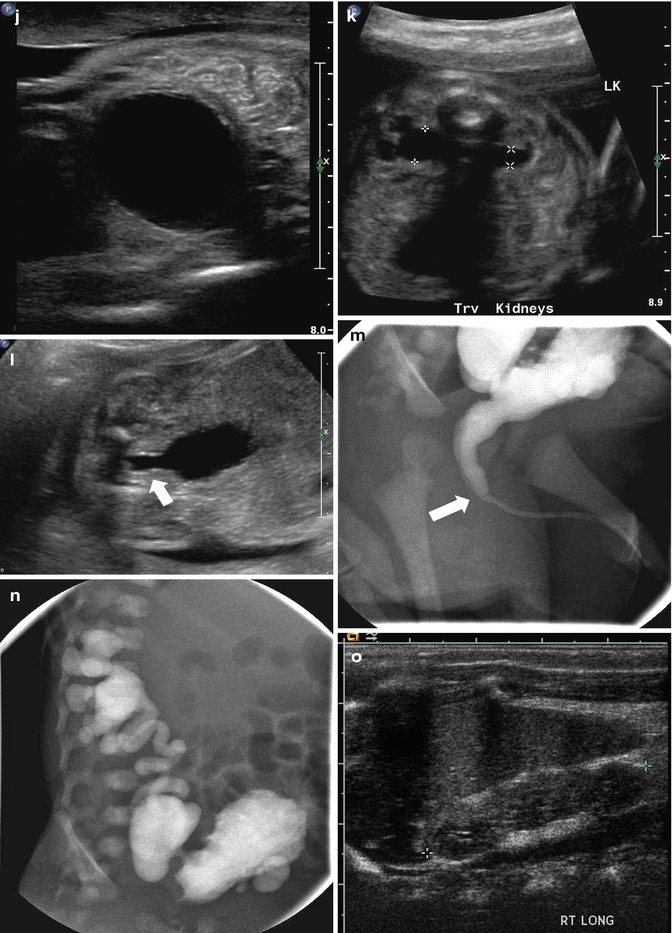

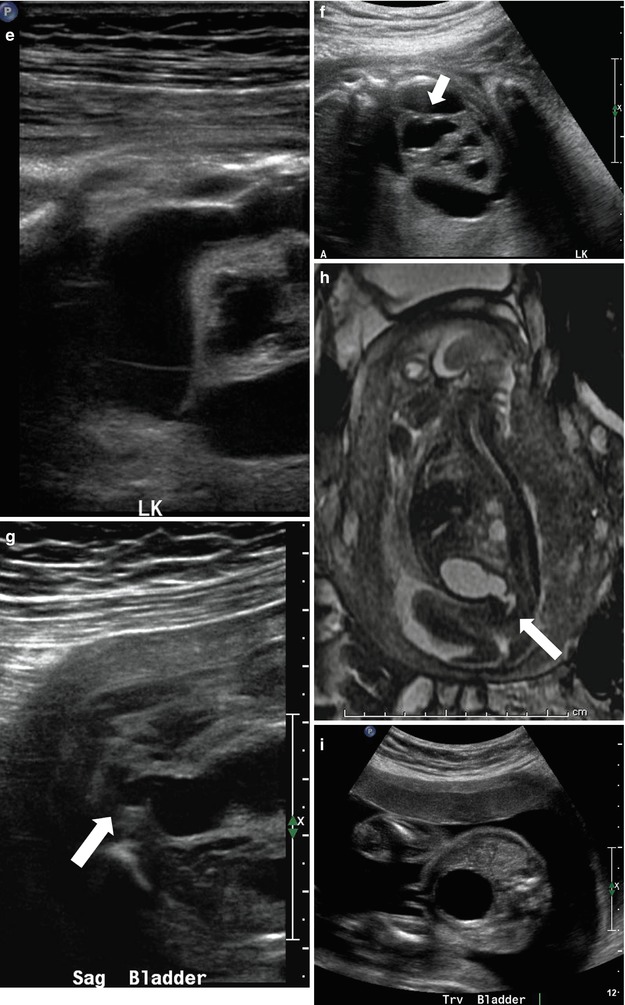

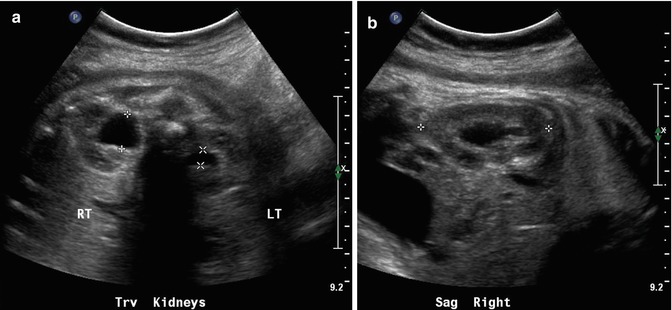

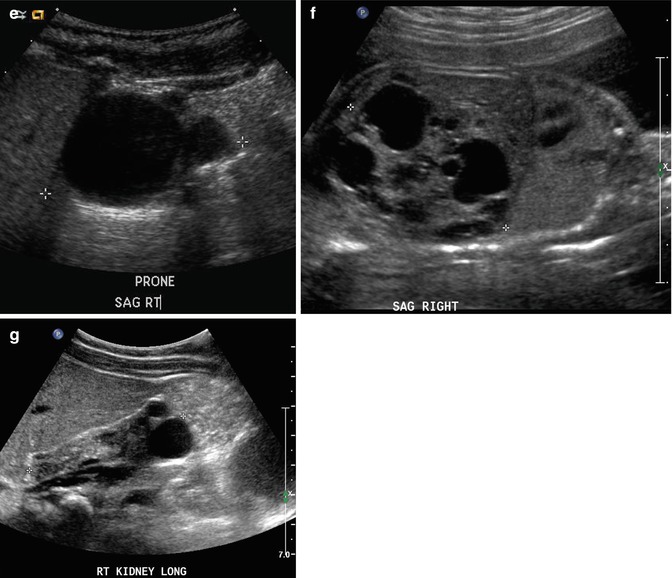

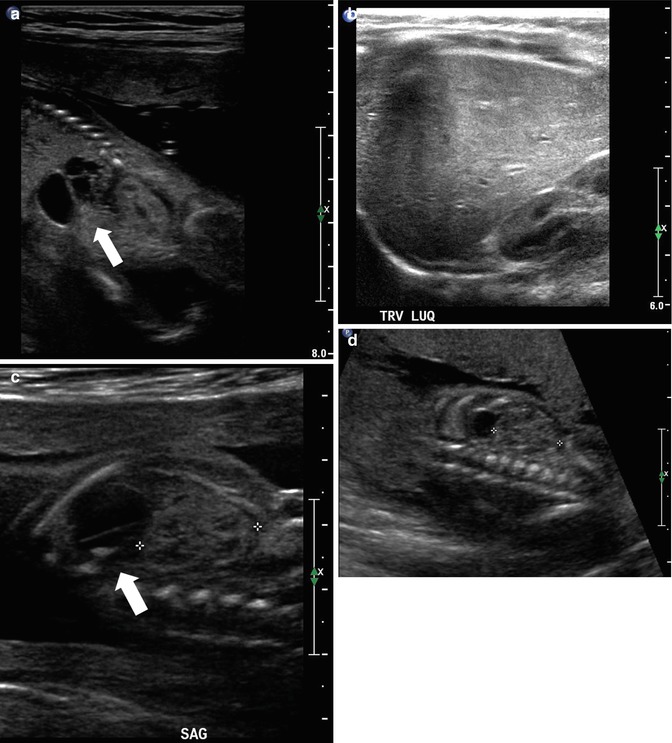

Fig. 8.5

On this 34-week fetal sonogram, we see moderate right and mild left fetal hydronephrosis in the transverse plane (a) and in the sagittal plane on the right (b). Postnatal sonography is fairly similar, with moderate right hydronephrosis, and very minimal residual pelviectasis on the left side (c and d). Voiding cystourethrography reveals bilateral, high-grade vesicoureteric reflux (e) and delay in drainage of refluxed contrast after voiding (f), suggesting the presence of a degree of concomitant, right-sided ureteropelvic junction obstruction. It is important to note that the left-sided fetal hydronephrosis was minor, but the documented, left-sided reflux was considerable on postnatal VCUG, indicating the poor sensitivity of sonography for identification of reflux

Evaluation of the renal cortex is also an important factor in the survey of the genitourinary tract of the fetus. The echogenicity of the renal cortex should be similar to that of the fetal liver. Increased echogenicity of the renal parenchyma may be associated with renal maldevelopment otherwise known as renal dysplasia [27, 28]. Cystic renal disease of the kidney can also be identified fairly early in gestation by an increase in the echogenicity of the renal cortex (Fig. 8.6). It would be important to differentiate between congenital cystic kidney disease which is bilateral and with a genetic cause (autosomal versus dominant polycystic kidney disease ADPCKD versus ARPCKD) versus multicystic dysplastic kidney (MCDK,) which is usually unilateral with no known genetic etiology. On fetal echography, ARPCKD displays striking features of bilateral, massively enlarged kidneys that are echogenic due to acoustic interfaces caused by the dilated tubules and cysts (Fig. 8.7). Features of multicystic dysplastic kidney as diagnosed prenatally include multiple cysts of variable sizes, no evidence of parenchyma or collecting system, and the possibility of contralateral compensatory hypertrophy (Fig. 8.8). The findings of hyperechoic kidneys in the fetus require postnatal evaluation as it may indicate some intrinsic abnormality of the renal parenchyma, although the outcomes may be quite variable [29]. Confusion may also arise with extrarenal cystic lesions which may mimic renal anomalies. For example, adrenal hemorrhage may give the appearance of an upper pole cyst. Careful, precise scanning can generally differentiate the kidney from the extrarenal lesion. Further diagnostic testing by MRI will provide additional anatomic detail (Fig. 8.9). Other abnormalities of the kidneys include anomalies of position and rotation as well as agenesis or hypoplasia, which are rare.

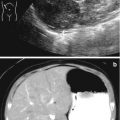

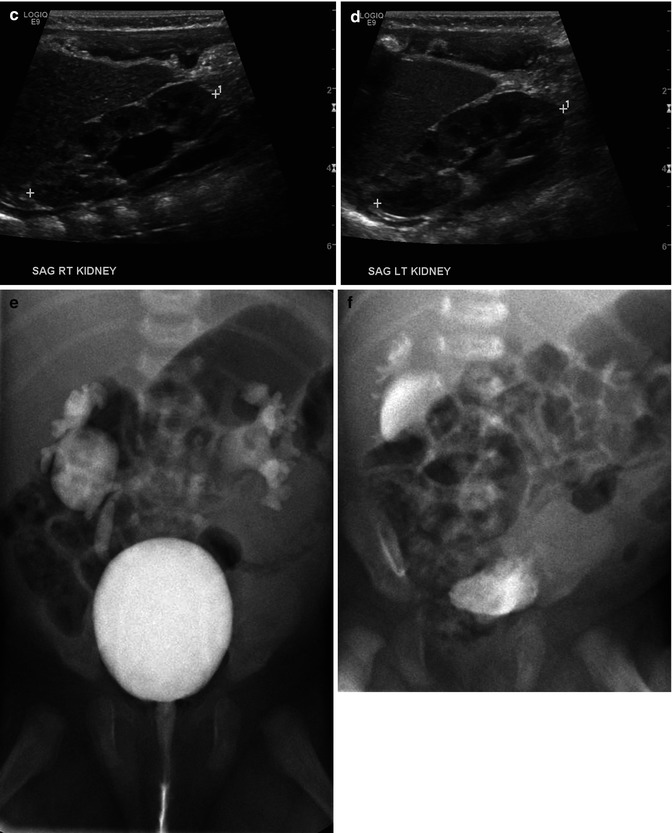

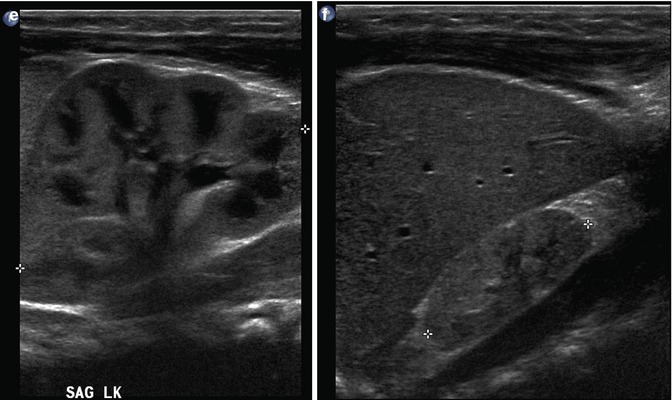

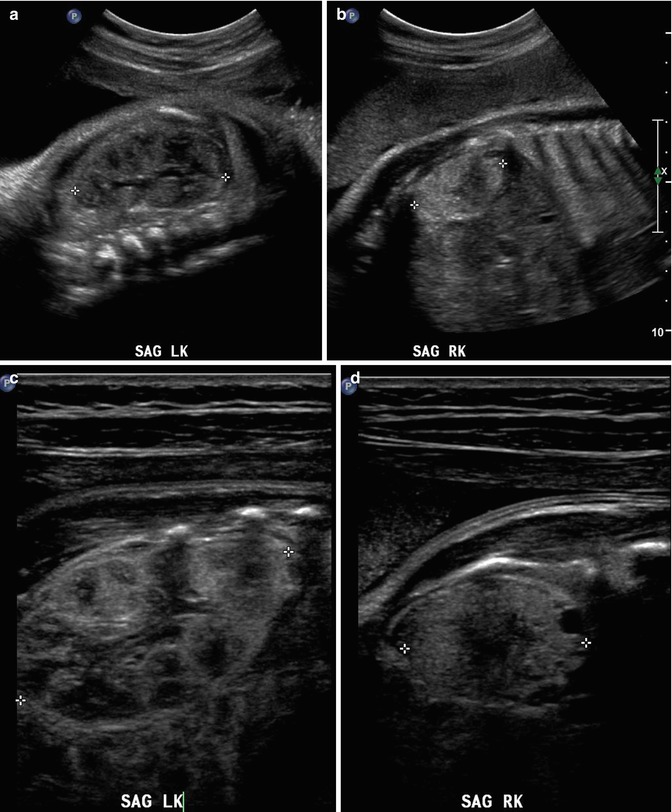

Fig. 8.6

This fetus was followed by sonography with a small, echogenic, dysplastic right kidney and a normal, compensatory hypertrophy of the left kidney. Sonography at 32 weeks shows the striking difference between the kidneys using a curved transducer (a and b) and linear probe views obtained on the same day show even greater detail (c and d), with at least one discernible cortical cyst on the right. Findings are confirmed after birth, at 1 month of age (e and f)

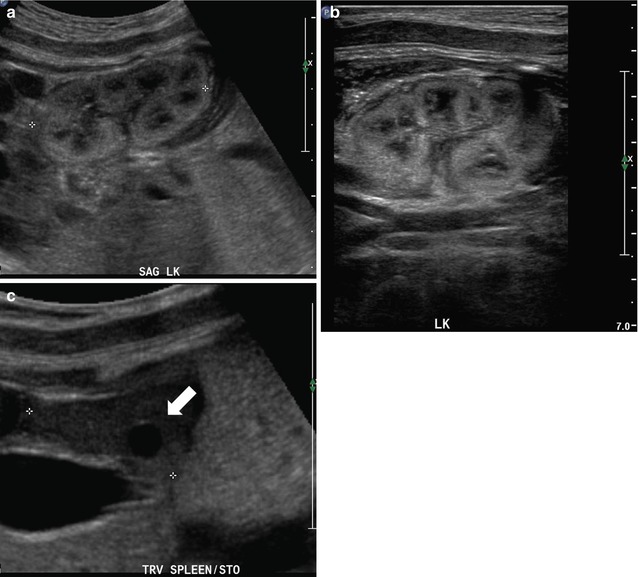

Fig. 8.7

At 32 weeks gestation, this fetus was shown to have bilaterally enlarged kidneys, with a brightly echogenic renal cortex (a). The linear probe shows that the kidney is so large that it reaches well below the level of the aortic bifurcation (b). Additional views of the fetal left upper quadrant reveal a single, simple cyst in the fetal spleen (c, arrow). This fetus proved to have autosomal recessive polycystic kidney disease (ARPKD)

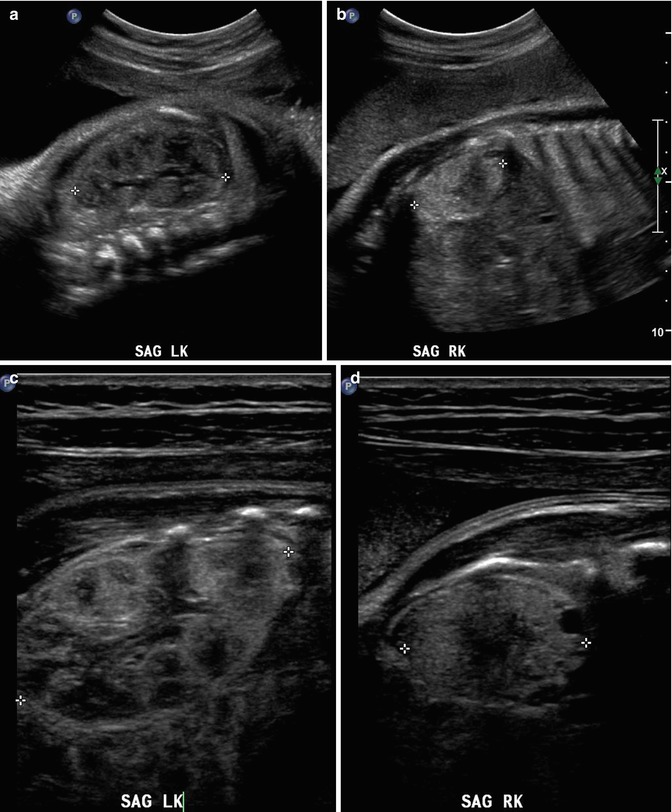

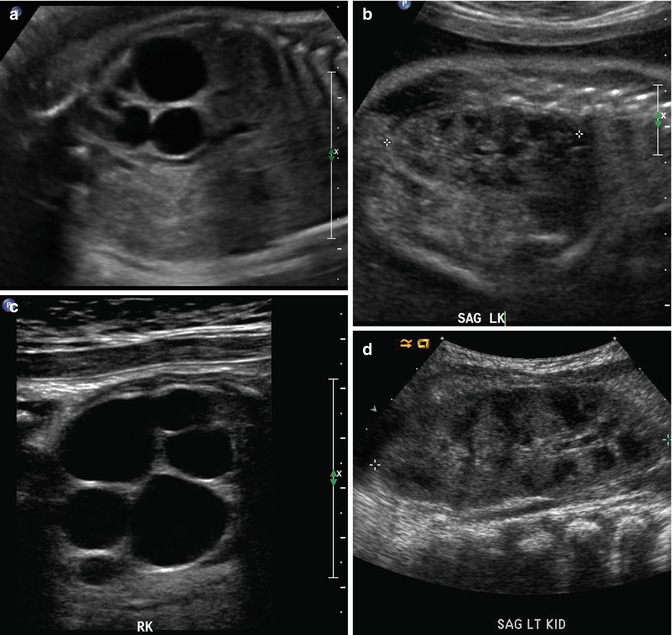

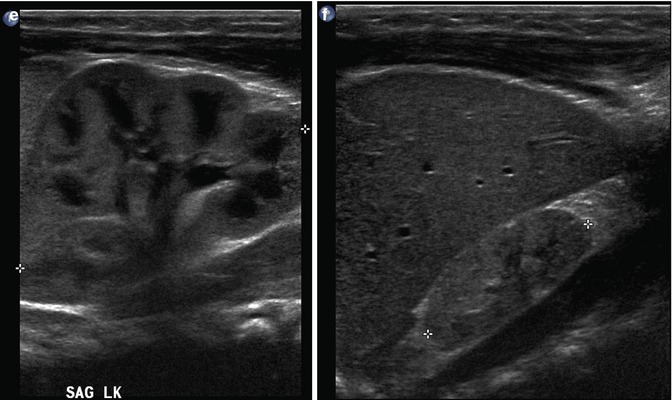

Fig. 8.8

Fetal sonography at 32 weeks gestation reveals a large conglomerate of cysts in the right renal fossa and a normal-appearing left fetal kidney, using a curved probe (a and b). With a high-resolution linear probe, further detail is revealed (c). This is the classic appearance of a multicystic dysplastic kidney. Sonography was performed 6 weeks after delivery, revealing the expected compensatory hypertrophy of the left kidney (d) and some interval involution in the cysts on the right side, as is typical (e). In a different fetus at 25 weeks gestation, we see another minor variation in the fetal appearance of multicystic dysplastic kidneys. This kidney is even larger than the first example, with some visible intervening echogenic, dysplastic renal parenchyma, and multiple scattered cysts (f). By 2 months of age, there had been considerable interval involution of this nonfunctioning dysplastic kidney (g)

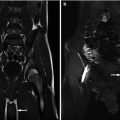

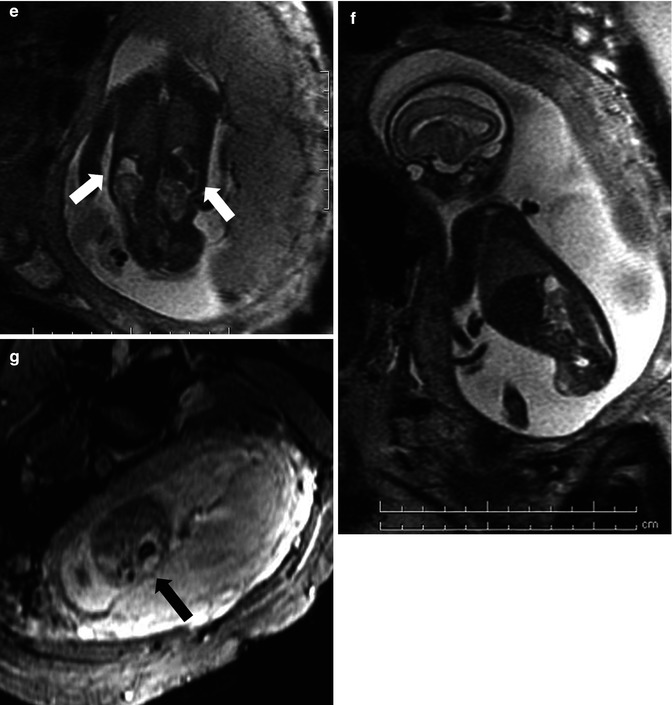

Fig. 8.9

This fetus was referred at 19 weeks gestation with the working diagnosis of left upper pole renal cysts. However, upon our assessment, it was clear that the kidney and the cystic conglomerate moved separately from one another on real-time sonography (arrow), suggesting that this was a cystic adrenal mass, likely evolving hemorrhage (a). On postnatal sonography, this had resolved entirely by 6 weeks of age (b). In another pregnancy, also at 19 weeks gestation, similar, bilateral cystic adrenal masses were also observed (arrow, c and d). It is interesting to note that this patient had also been referred with the erroneous diagnosis of upper pole renal cysts. Single-shot FSE T2 images in the coronal (e, arrow) and sagittal (f) planes reveal complex, bilateral adrenal masses with both T2 bright and T2 dark material, suggesting the presence of hemorrhage. This is proved on the axial gradient echo sequence, with marking, the so-called blooming artifact of Fe products (arrow, g)

Any abnormalities of the renal collecting system and/or renal parenchyma should be communicated to the pediatrician who will then decide whether or not further postnatal evaluation is required. Early identification of renal or bladder anomalies warrant prenatal counseling by a pediatric urologist in order to ensure adequate postnatal evaluation and management.

Dilatation of the ureters may also be noted on prenatal ultrasound. If it is unilateral, the dilation is usually associated either with an obstructive process at the distal end of the ureter (ureterovesical junction obstruction or megaureter) or with reflux. Unilateral dilatation of the renal collecting system and ureter does not usually warrant any further intervention during pregnancy but will require postnatal evaluation. Bilateral dilatation of the ureters, on the other hand, warrants careful evaluation of the bladder to look for intravesical obstruction. Other anomalies associated with bilateral dilatation of the renal collecting system and ureters include prune-belly syndrome as well as high-grade vesicoureteral reflux.

Duplication anomalies of the kidneys can be identified later in gestation when the renal parenchyma may be seen to have a band of tissue separating the renal collecting system one or both showing some degree of dilatation (Fig. 8.10). Duplication anomalies diagnosed prenatally should raise the suspicion for vesicoureteral reflux (usually to the lower pole), ureterocele, and ectopic ureters and warrant postnatal evaluation.

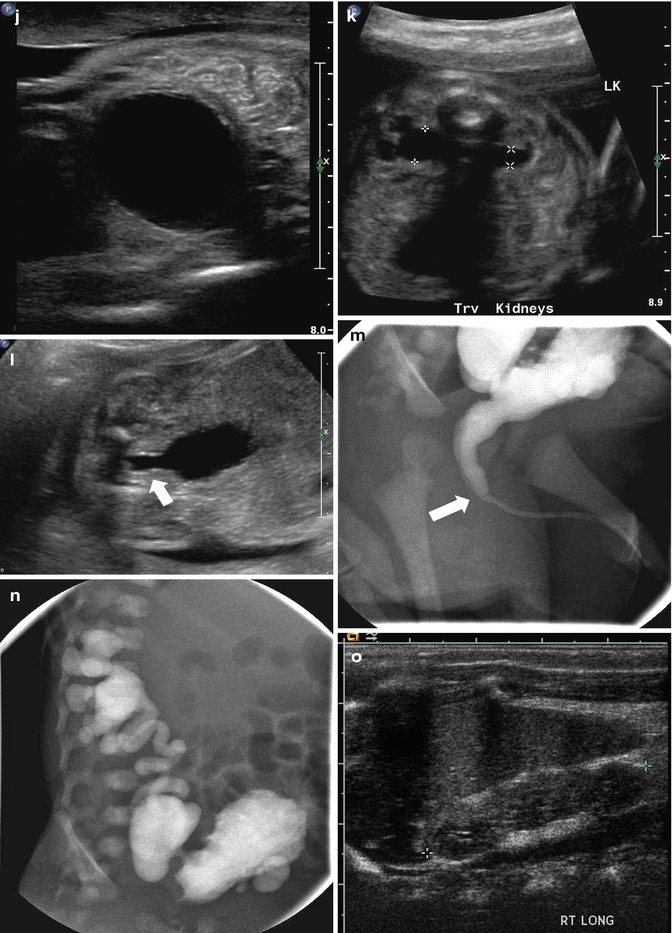

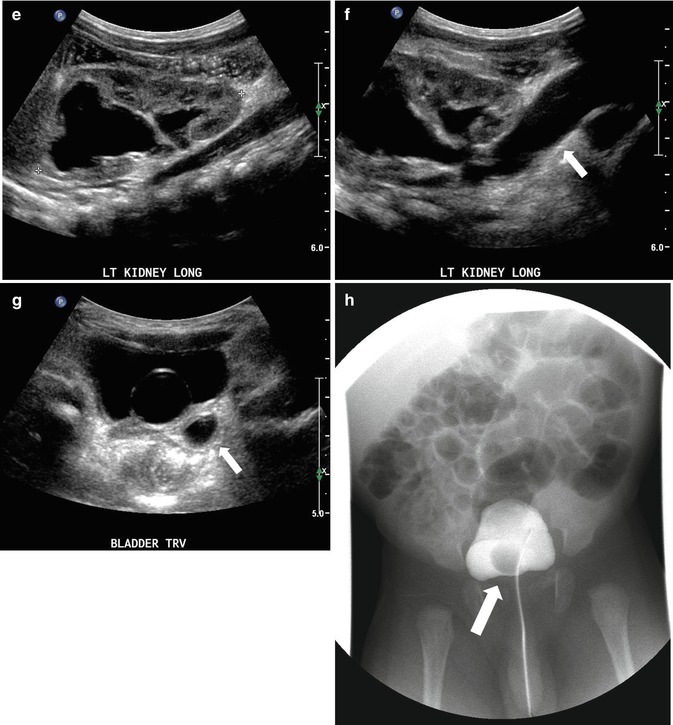

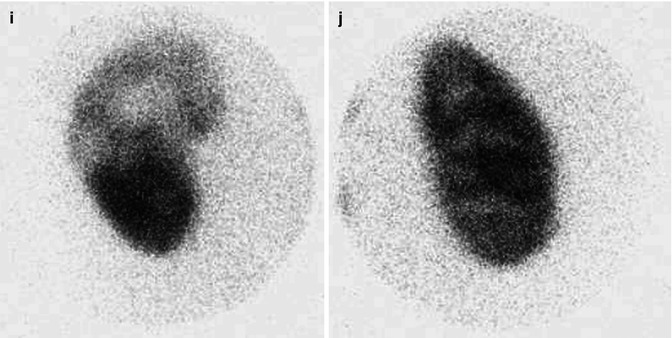

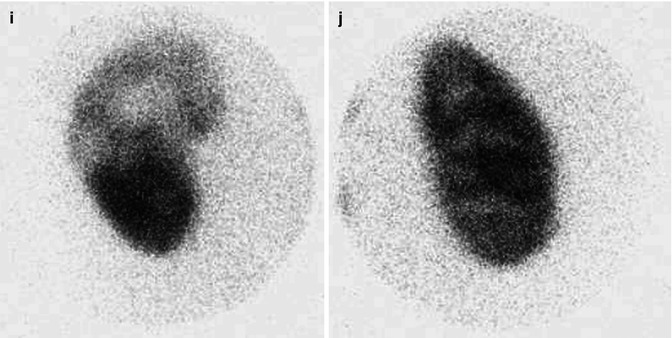

Fig. 8.10

At 33 weeks gestation, this fetal sonogram reveals a duplex left kidney, with both upper and lower pole hydronephrosis (a), as well as upper pole hydroureter (b, arrow). A 12 MHz linear probe can be used to obtain additional detail in this fetus as the mother is slender, so less depth of penetration is required (c), showing disproportionate distention of the upper pole pelvis (arrow). With careful attention to the moderately full fetal bladder, a ureterocele is visible (d, arrow). After delivery, initial evaluation with sonography (e, f, g) and voiding cystourethrography (h) confirms the presence of a duplex kidney with disproportionate upper pole hydroureteronephrosis (e, f, g, arrow), associated with an obstructed ureterocele (h, arrow), but no vesicoureteric reflux. Scintigraphy was performed at 2 months, and posterior views of the left (i) and right kidneys (j) reveal clearly diminished function of the left upper pole cortex

Absence of a one or both of the kidneys can be observed prenatally. It is important to ensure that the apparently absent kidney is not ectopic (usually in the lower abdomen or bony pelvis) before making a diagnosis of renal agenesis. Bilateral renal agenesis is rare and occurs in 1–4,800 to 1 in 10,000 births [30]. Unilateral renal agenesis occurs in 1 in 1,100 births. There is usually a male predominance (75 %). There may be an autosomal recessive inheritance associated with this condition. Unilateral renal agenesis should be confirmed postnatally. Bilateral renal agenesis is thought to be incompatible with survival of the fetus and is associated with gradual or sudden drop in amniotic fluid leading to anhydramnios low or inexistent levels of amniotic fluid as the pregnancy progresses leading to fetal crowding and profound lung hypoplasia (Potter’s syndrome) [31].

Renal and suprarenal masses will, occasionally, may be identified prenatally. These include mesoblastic nephroma which is a benign lesion of the kidney. Adrenal hemorrhage may be also identified as a large hypo- or hyperechoic mass above the kidney (Fig. 8.9). Neuroblastoma can also be diagnosed prenatally typically in a suprarenal position but can occasionally be seen in the abdomen or the retroperitoneum.

Postnatal evaluation is dictated by the prenatal findings. No guidelines have been set up for postnatal evaluation of patients diagnosed with hydronephrosis. However, currently it would be reasonable to suggest that any child whose AP diameter of the renal pelvis is <7 mm, probably does not require any follow-up postnatally. A postnatal ultrasound certainly is not an unreasonable approach for patients with an AP diameter of 8 mm or greater. The timing of the first postnatal ultrasound is a matter of debate. An early evaluation (within the first days of life) may allow for early identification of those fetuses who may require follow-up. It is important to realize, however, that sonography during the first 24 h of life may significantly underestimate the degree of hydronephrosis because of physiologic oliguria, so most authorities recommend evaluation after the first few days of life, or later, unless a serious abnormality, requiring urgent treatment, is suspected. Evaluation for vesicoureteral reflux or posterior urethral valves would be in the form of a voiding cystourethrogram (VCUG); for an obstructive process, a MAG 3 radioisotope study would be indicated.

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree