Daniel Do • Marcelo Guimaraes

Priapism is defined as the state of tumescence in the absence of sexual stimulation persisting beyond 4 hours and can be divided into ischemic or low-flow and nonischemic or high-flow classifications.1 Overall incidence of priapism is reported to be low within the general population (0.5 to 0.9 cases per 100,000 person-years).2–4 Resolution of priapism while preserving erectile function remains the goal of treatment strategies.1

Ischemic priapism, also known as veno-occlusive priapism, represents approximately 95% of cases.5 This stems from persisting cavernosal smooth muscle relaxation with resultant failure of contraction, which in turn causes compartment syndrome, increasing intracavernosal anoxia, and acidosis. Immediate treatment is required as tissue damage may begin in as little as 12 hours from onset.6 Most patients suffering from ischemic priapism for duration greater than 24 hours experience complete erectile dysfunction.7 Treatment includes pain control, intracavernosal injection of a sympathomimetic drug, aspiration of the corpora, and surgical shunting; endovascular intervention typically has no significant role in treating low-flow priapism. Sickle cell disease represents the most common cause of ischemic priapism in childhood and is found in 63% of cases. In adults, 23% of cases are attributable to sickle cell disease, with a reported lifetime probability of development in 29% to 42% of patients.4,5,8,9 Given this, concomitant workup and treatment of underlying hematologic blood dyscrasias are often performed on presentation. As endovascular embolic therapy has a limited role in the treatment of ischemic priapism, this chapter will primarily focus on nonischemic priapism.

Nonischemic priapism, also known as arterial priapism, was first described by Burt et al.10 in 1960 and represents a relatively rare phenomenon. It is most commonly a result of perineal or penile trauma, which results in an abnormal fistulous communication typically involving the cavernosal artery and adjacent penile sinusoidal spaces.5,11 Additional causes related to metastatic disease and intracavernosal injections have been reported,12,13 with spontaneous resolution rates of up to 62%.1 High-flow priapism is not considered a urologic emergency as there is maintained arterial inflow through the fistula, allowing oxygenation of the cavernous tissue. Although not at risk for ischemic damage, long-term sequelae may occur from possible structural damage secondary to the increased and persistent arterial inflow.13–15 Treatment strategies for managing nonischemic priapism include watchful waiting, application of ice packs, ultrasound-guided compression, surgical intervention, endovascular introduction of methylene blue, and endovascular embolization.14,16,17

Endovascular techniques have been described using both temporary and permanent embolic agents, including autologous blood clot and gelfoam as well as microcoils, acrylic glue, and particles, respectively.1,4,18,19 Endovascular intervention, first reported by Wear et al.19 in 1977, is considered the standard of care beyond conservative treatment, with reported success rates approaching 90%. The risk of erectile dysfunction has been reported to be as low as 5% with use of temporary embolic agents.1

Surgical options including shunting, penile exploration, and direct arterial fistulous ligation are considered a last resort treatment strategy.1 Overall success rate of 20% for shunt surgery and 63% for ligation surgery have been reported.1,13

CLINICAL APPLICATIONS

Correct identification of priapism classification is critical as endovascular management plays a role only in cases of nonischemic priapism. A typical clinical history for nonischemic priapism includes an episode of trauma followed by a nonpainful, partially rigid erection. The onset of priapism may be delayed up to 2 to 3 weeks and can be secondary to arterial spasm or ischemia.4 Physical examination will confirm a partially tumescent corpora carvernosa, and routine laboratory testing is performed to exclude anemia and possible hematologic abnormalities, none of which would be expected with nonischemic priapism.4 Acquisition of cavernous blood gas analysis should reflect arterial blood color and normal levels of pO2, pC02, and pH.

Color duplex ultrasonography of both the penis and perineum is recommended. Visualization of normal or increased blood flow velocities within the cavernosal arteries confirms a diagnosis of nonischemic priapism.16,20 Additionally, size of the cavernosal artery may demonstrate enlargement greater than reported upper normal limits of 0.7 mm.21 Direct visualization of the causative fistula and/or pseudoaneurysm is often encountered and can assist in localization and preprocedural planning.1,4,20,22 Initial treatment strategy can encompass observation in conjunction with ice packs and site-specific perineal compression. Spontaneous resolution of nonischemic priapism has been reported in up to 62% of cases.1 However, observation alone can pose a theoretical risk of secondary tissue fibrosis due to excessive, constant arterial inflow resulting in erectile dysfunction.13–15,23 Timing of definitive therapy remains institution and patient dependent.

TECHNIQUE

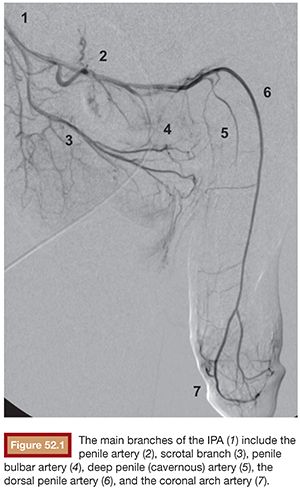

Before diagnostic angiography, diagnosis should be confirmed with corporal blood gas analysis and ultrasound. Because the arterial inflow is maintained, there should be adequate time for scheduling and planning before intervention. Foley catheter placement should be considered to improve visualization of the pelvic arteries, especially of the internal pudendal artery (IPA) origin. The IPA is typically the smallest branch of the anterior trunk of the internal iliac artery and is responsible for the external genitalia blood supply. Branches of the IPA include the perineal artery, penile artery, penile bulbar artery, deep penile (cavernous) artery, and the dorsal penile artery (Fig. 52.1). It is important to keep in mind that the right and left sided circulations may communicate through branches at the level of the bulb of the penis and between the obturator and IPA.

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree