George M. Bridgeforth, David S. Wellman, and Charles Carroll IV

A 60-year-old woman fell on her outstretched wrist and hand when she tripped on a sidewalk. She presents with pain and tenderness in her elbow.

CLINICAL POINTS

- Fractures and dislocations of the radial head are usually caused by trauma.

- Pain is prominent with passive flexion/extension of the digits.

- Wrist pain may occur.

- Compartment syndrome is uncommon.

Clinical Presentation

Elbow fractures account for 6% to 7% of all fractures. Radial head fractures are the most common type of elbow fracture in adults; they account for approximately 30% of all elbow fractures. Olecranon fractures account for an additional 10% to 20%. Distal humeral fractures are uncommon (2% of all elbow fractures), capitellar fractures are even more uncommon (0.5%), and trochlear fractures are rare. Fractures of the radial head and neck generally result from a hard fall on the arm, with the hand outstretched. The wrist is usually in an extended position.

In a patient presenting with elbow pain, the examiner must maintain a high index of suspicion and carefully palpate the radial head as there may be a paucity of clinical findings. Often, patients display only a loss of terminal extension. The examiner must keep in mind other conditions on the differential diagnosis: compartment syndrome, medial epicondylitis, and biceps rupture.

While neurological findings are more frequently associated with ulnar neuropathies from a medial epicondylitis, a high index of suspicion must be kept for compartment syndrome. Compartment syndromes are characterized by marked swelling of the forearm, coldness, pallor, numbness, and diminished pulses. Pain is the first clinical sign.

Patients with a medial epicondylitis of the elbow have pain and soreness over the medial epicondyle with resisted wrist flexion. When it is present, an associated ulnar entrapment is characterized by numbness and sensory loss along the ulnar border of the forearm. Associated findings with ulnar entrapment include a sensory loss of the ulnar border of the ring finger and the little finger. Patients may also exhibit interosseous muscle weakness of the hand, characterized by an inability to hold a small piece of paper between the fingers when it is removed by an examiner.

Patients with acute biceps tears complain of feeling a “pop” in the upper arm while lifting. Extreme tears present with a bulging knot in the arm. Moderate tears present with pain soreness and tenderness with pronounced swelling and bruising over the medial biceps. The ecchymosis and swelling may extend into the antecubital fossa and medial upper forearm. Range of motion, including supination, is limited. With complete tears of the biceps tendon, the biceps tendon cannot be palpated when the elbow is flexed with the hand supinated (palm facing upward) (Fig. 33.1).

FIGURE 33.1 A sagittal image of the left elbow, demonstrating a complete tear of the biceps tendon (arrow) from its radial insertion with approximately 4 cm of retraction.

PATIENT ASSESSMENT

- Tenderness of the radial head with palpation

- Soreness and swelling around the elbow

- Impaired range of motion

- Possible open fractures

During the physical examination, the clinician should:

- palpate the radial head for tenderness (radial head fracture).

- palpate the olecranon and distal humerus for tenderness (associated fractures).

- assess range of motion in supination, pronation, flexion, and extension. Fracture fragments may restrict motion. The contralateral extremity is useful for comparison.

- check for elbow dislocations (articulation between ulna and humerus).

- assess for concomitant distal radius (wrist) fracture, scaphoid fracture, carpal injury, hand fracture, and shoulder injury.

- assess for soft tissue injuries by palpating around the medial and lateral collateral ligaments and checking varus/valgus stability.

- check for neurovascular compromise (cold, cyanotic limb, absent, or diminished pulses).

Radiographic Evaluation

NOT TO BE MISSED

- Elbow contusions

- Elbow dislocations

- Coronoid fractures

- Olecranon bursitis/fractures

- Medial or lateral epicondylitis

- Torn collateral ligaments

- Septic joint

- Septic bursitis

- Forearm and biceps strains; biceps tears

- Gout

- Rheumatoid arthritis

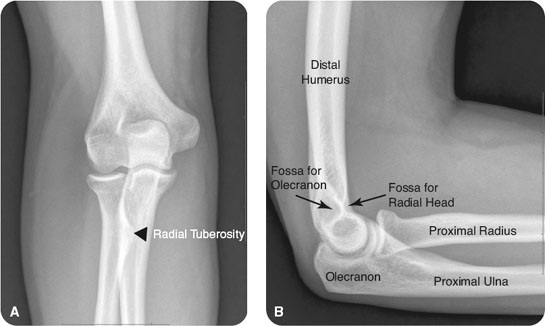

Plain radiographs should be obtained. A complete elbow series consists of anteroposterior (AP), lateral (Fig. 33.2), and oblique views of the elbow with the beam centered on the radiocapitellar joint. In more severe trauma settings, the radial head fracture can be isolated or exist in conjunction with other elbow injuries, with possible associated fractures, dislocations, subluxations, and ligament injuries. A computed tomography (CT) scan may be ordered to evaluate these injuries further and to assist with preoperative planning. Magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) scans are helpful in defining soft tissue injury components.

FIGURE 33.2 Anteroposterior (A) and lateral (B) views of a normal right elbow.

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree